Advertisement

Answering Your Questions About Reactor:

Right here.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Everything in one handy email.

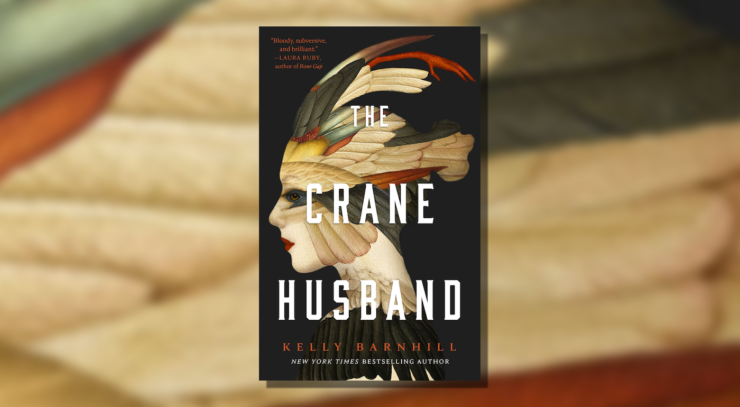

The Book That Reached into the Switchboard of My Mind and Flipped Everything On

Kelly Barnhill

Kelly Barnhill

Kelly Barnhill is the author of three fantasy novels for children—The Witch’s Boy, Iron Hearted Violet and The Mostly True Story of Jack. She has also written several short stories for grown-ups, which can be found in Postscripts, Weird Tales, Lightspeed, Clarksworld and other publications. She has received fellowships from the Jerome Foundation, the Abigail Quigley-McCarthy Center for Women and the Minnesota State Arts Board. She lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota with her architect husband, her three Most Remarkable Children, and her ancient, possibly-immortal dog.

Website

Latest from Kelly Barnhill

Showing 6 results

“Writers are liars my dear, surely you know that by now?”

Neil Gaiman, The Sandman