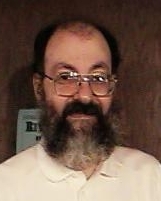

Harry Norman Turtledove is an American fantasy and science fiction writer, born in Los Angeles, CA on 14 June 1949. A Caltech dropout, he eventually attended UCLA and received a Ph.D. in Byzantine history in 1977.

In the 1980s, Turtledove worked as a technical writer for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. In 1991, he left the LACOE and turned to writing full time. From 1986-1987, he served as the Treasurer for the Science Fiction Writers of America. He has written under several pseudonyms, including Eric G. Iverson, Mark Gordian, and H. N. Turtletaub.

Turtledove has received numerous awards and distinctions, including the HOMer Award for Short Story in 1990 for "Designated Hitter," the John Esthen Cook Award for Southern Fiction in 1993 for

Guns of the South, and the Hugo Award for Novella in 1994 for

Down in the Bottomlands. "Must and Shall" was nominated for the 1996 Hugo Award for Best Novelette and received an honorable mention for the 1995 Sidewise Award for Alternate History.

The Two Georges also received an honorable mention for the 1995 Sidewise Award for Alternate History. The Worldwar series received a Sidewise Award for Alternate History Honorable Mention in 1996.

Publishers Weekly called him the "Master of Alternate History."

He is married to mystery writer Laura Frankos and they have three daughters: Alison, Rachel, and Rebecca.

Wikipedia |

Author Page |

Goodreads

Harry Norman Turtledove is an American fantasy and science fiction writer, born in Los Angeles, CA on 14 June 1949. A Caltech dropout, he eventually attended UCLA and received a Ph.D. in Byzantine history in 1977.

In the 1980s, Turtledove worked as a technical writer for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. In 1991, he left the LACOE and turned to writing full time. From 1986-1987, he served as the Treasurer for the Science Fiction Writers of America. He has written under several pseudonyms, including Eric G. Iverson, Mark Gordian, and H. N. Turtletaub.

Turtledove has received numerous awards and distinctions, including the HOMer Award for Short Story in 1990 for "Designated Hitter," the John Esthen Cook Award for Southern Fiction in 1993 for

Guns of the South, and the Hugo Award for Novella in 1994 for

Down in the Bottomlands. "Must and Shall" was nominated for the 1996 Hugo Award for Best Novelette and received an honorable mention for the 1995 Sidewise Award for Alternate History.

The Two Georges also received an honorable mention for the 1995 Sidewise Award for Alternate History. The Worldwar series received a Sidewise Award for Alternate History Honorable Mention in 1996.

Publishers Weekly called him the "Master of Alternate History."

He is married to mystery writer Laura Frankos and they have three daughters: Alison, Rachel, and Rebecca.

Wikipedia |

Author Page |

Goodreads