Contrary to How it Seems, Humans Band Together During and After Disasters

Comment number:

10

Advertisement

Showing 16 results

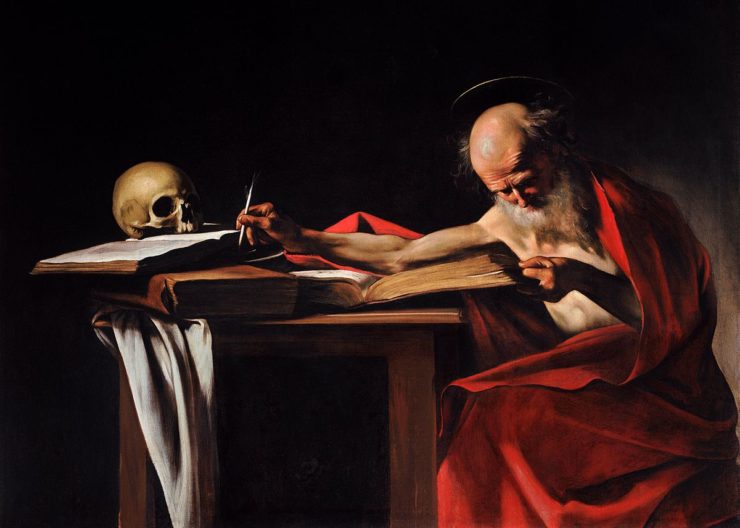

“Writers are liars my dear, surely you know that by now?”

Neil Gaiman, The Sandman

For compliance with applicable privacy laws: