According to a June piece in Esquire, short books “are finally getting their due.” I suspect this news may feel a bit belated to many Tor.com readers; you have, I’m sure, been aware of Tordotcom Publishing’s novellas for years now. (SFF being SFF, the Esquire piece mentions a whole lot of other programs and lines of short books, but not this one.) In July, The Atlantic offered some short summer reading suggestions, at least one of which was immediately added to my “things I should definitely read” list.

The thing is, I kind of thought I hated short books.

“Hated” is maybe a strong word. Was not a fan of. Did not generally care for. Never gravitated towards. This is probably not an uncommon feeling among SFF readers who grew up in a certain era without access to genre magazines or other sources of short fiction. If I was going to get a book out of the library or spend my holiday gift certificates on it, I wanted it to be as thick as possible. As much book as my dollars could buy; as many pages as I could get from the library at once. I was pretty sure I respected novellas, but I did not particularly want to read them.

And when they’re not done well, there’s a reason for that: Sometimes a novella feels like a novel without an ending, or a short story that went on too long. Knowing how long to write a story—or a column, or an essay, or a blog post—is a real skill, and one that any writer might struggle with. It doesn’t always work out right. You run long; you leave an idea out.

But when you hit the balance, something magical occurs.

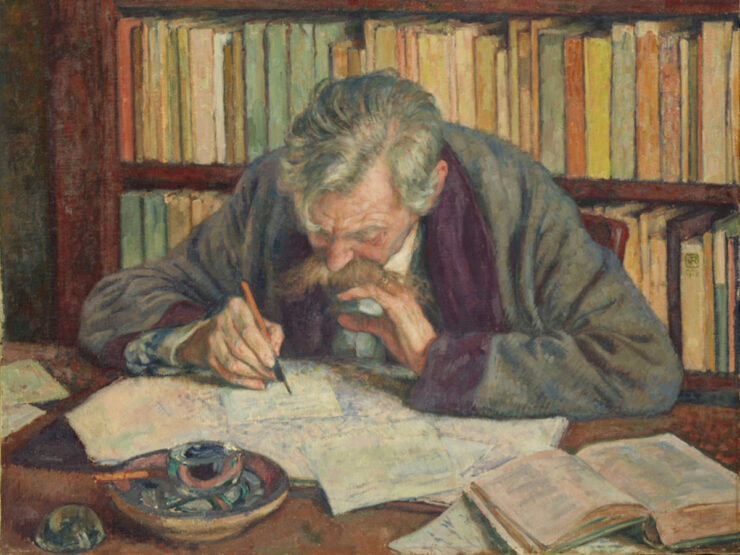

It started, for me, with short nonfiction. Marina Benjamin’s Insomnia. Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. Thin books, rich with ideas, clean sentences, things that resonated. There’s no room for clutter, in a short book, and while my brain frequently adores narrative clutter—stuff everything in there! Give me the history of some strange corner of the world, Neal Stephenson-style!—it has, of late, wanted something else. Something you might call “quieter,” even though the stories are not necessarily quiet. Something from which everything unnecessary has been gently removed.

I read two Chloe Hopper novels in a day: A Child’s Book of True Crime and The Engagement, neither of which are SFF but both of which are unnerving and wily, taut tales you cannot disengage from—and trust me, I tried, but once I had picked up those narrative threads I needed to follow them all the way to their uncomfortable ends. (I truly don’t understand how The Engagement, a very disquieting Australian Gothic of sorts, has not been made into a movie.)

I read Camilla Grudova’s crumbling-movie-theater-set Children of Paradise; I read Sasha LaPointe’s elegant memoir Red Paint. I read Play It As It Lays, and then I needed to lie down. (Didion will do that to you.) I read Nghi Vo’s upcoming Mammoths at the Gates and spent the whole book wanting to cry for reasons I could never quite put my finger on. I started looking for more short books in my tower of unread books: What here is under 200 pages? What can I eat up like a perfect snack? What does my feral-child brain wish to graze on next?

There are theories—some of them included in that Esquire piece, and some of them quite depressing—about why we, culturally, might like short books right now. Short attention spans. Rising hardcover prices. (I don’t feel like the short books are generally that much cheaper, but I also haven’t done a survey.) The simple satisfaction of finishing a book and moving on to the next one. Spending your time with many minds, many kinds of brilliance, instead of submerging in one for a long, slow time.

It’s those last two that make short books feel so summery to me—this summer, this moment, this year of fires and floods and storms. Shorter books are not necessarily light and swift, thematically speaking, but they can feel that way all the same, especially when you have become accustomed to long, tangled tales, epics and trilogies and narrative arcs that play out in multiple points of view, multiple volumes, multiple galaxies.

I have had it with multiverses for the time being. I have had it with more versions of superheroes, more versions of worlds, stories that are so busy offering more, more, more that they forget to make us care about what’s right in front of us. There is a point at which exploring every corner of a fictional universe stops feeling like exploring and starts feeling like exploiting, and more than one once-beloved franchise is there.

The short books aren’t just an answer to long books. The short books are a counterpoint to spinoffs and sequels and having to watch TV series to understand what’s happening in a movie and needing a quick wiki check to remember the name of Tertiary Character #47, whose death was meant to be very moving in the seventeenth episode of the third spinoff, except that we all forgot his name already.

We are in a moment that is reminding us, in so many ways, that many of the stories we love are or have become commerce. Companies don’t even want to pay the people who write those stories; how are we to maintain our illusions, our idealistic notions that these stories are on display because they are meaningful and important, when we’re constantly being reminded that their creation means nothing to the people who hold the purse strings?

The stories are—can be—meaningful, important, the things dreamt up by individual writers and storytellers. (Let us not say “creators.” Let us not say “content.”) I want to believe, like Fox Mulder, but I want to believe that stories are told because people need to tell them. Not because some guy in a fancy suit thinks he’s going to make enough bank to buy a second yacht.

This moment in time requires a nigh supernatural ability to suspend one’s disbelief.

But a short book is not a franchise. A short book is probably not making anyone wealthy. (There are, as ever, exceptions. Probably.) A short book is not likely to balloon into a multiverse (unless it’s a comic book, perhaps, and even then it might take decades). A novella is ripe for adaptation, it’s true. If only the people in charge of adaptations realized that novellas are all beautiful movies waiting to be made, without even a bunch of stuff you have to take out in order to fit your runtime or make the test audiences happy.

But then they might stop being perfect little worlds, and start mutating into nightmares.

Should you find yourself tired, scattered, sweaty, worn-out, feeling like the end of summer coming for your mental well-being; if you just want to be somewhere else for a while, not overcommitted, not making a cheat sheet of character names: I recommend a novella. A 200-page novel. A standalone, brief and powerful, or a novella in a series that does not demand you remember every detail from every previous volume. Maybe Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Paradises Lost” (Lee Pace agrees with me) or Olga Ravn’s The Employees or any one of Nghi Vo’s Singing Hills stories or a Rachel Cusk book or Alan Watts’ Become What You Are or any number of award-winning novellas and novelettes you might find on this very website.

The epics will still be there, sprawling, immersive, rich. Excellent for winter. But for summer, I vote for the concise, the elegantly brief, the contained.