Legendary Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies director Chuck Jones shared this recollection in his memoir, Chuck Amuck: At one point, the studio had a much-loathed (at least by Jones) business manager who liked to sneak down to the staff rooms to make sure no one was slacking off on the company dime. Whenever he came lurking about, an especially vigilant crewmember would trigger signal lights across the facility, so that when the manager got to the animators’ workspace, he’d find the room a beehive of activity, whether or not the staff had been lollygagging mere seconds before.

It was a different situation, though, when he got to the story room, where directors like Jones, Friz Freleng, and Robert McKimson—plus their associated writers—hung out. There, he’d find the entire crew in a state of intensive goldbricking—one guy would be napping; another would be casually quaffing a Coke; in an especially inspired touch, a creative would promptly stop work, crumple up the sheet of paper, and pick up a racing form. If the manager dared tut-tut the loafers, they’d tut-tut him right back, further confusing the guy. And later, should he sneak back to see if his admonitions had had any effect, he’d discover the staff still diligently lollygagging, only now one wall would be plastered with fifty or so storyboard drawings. The poor schmuck never figured out how the cartoons were getting made.

I’ve no reason to doubt that this scenario happened—maybe even on a daily basis. Yet, reading between the lines, there’s a certain Chuck Jones-ness to the story—it bespeaks a clean symmetry in the contrast between what the manager encountered with the animators as opposed to what he witnessed with the directors. It’s not unlike when, in Jones’ Deduce, You Say (1956), Daffy Duck and Porky Pig—playing Holmes and Watson surrogates—take turns interrogating a suspect, with Porky consistently extracting solicitous responses from the thug while Daffy can only provoke violence. And the ironic capper of that suddenly drawing-bedecked wall has echoes of Bugs Bunny giving the audience a sly glance and a wry tilt of an eyebrow to close out a cartoon. However accurate Jones’ recounting is, the story also serves as a reflection of his methodical nature, a signature trait that the director would imbue in his cartoons.

Buy the Book

Dead Country

All through Chuck Amuck, Jones enumerates various rules he developed that would ultimately transform the Looney Tunes stock company. Bugs Bunny is no longer a wise guy, Brooklynese trickster, but a sophisticated, insouciant adversary who only retaliates when provoked. Daffy Duck went from a wacky radical to a desperate egoist, perpetually sabotaging himself in pursuit of self-aggrandizement. And stories would play out with near-scientific precision, getting to the point where, in the cartoon Fair and Worm-er (1946), Jones graphically shows a bird following a logic path that leads him to realize that he can defeat the cat that’s chasing him by helping a dog chasing the cat.

Fair and Worm-er is notable for another reason: It represents Jones’ and his writers’—notably Michael Maltese and Tedd Pierce—initial attempt to deconstruct the whole notion of a chase cartoon. Here, they try to get to the core of the concept by paradoxically escalating it to the point of absurdity: An apple gets pursued by a worm, who’s chased by a bird, who’s followed in turn by a dog, who’s pursued by a dog catcher, who’s intimidated by his wife, who’s antagonized by a mouse (“Ahhhhh! A mouse! A mouse! A mouse! A mouse!”), with a cameo appearance by Pepé le Pew—who had debuted the year before—serving as a kind-of all-purpose spoiler. The further the hunt progresses, the more rigorous the gags get—entering a lumberyard allows the characters to stack on top of each other, unaware that their target is right above their heads; in escaping Pepé, they progressively slam into a hole which grows to follow their ever-increasing outlines, then shrinks back down as each individual exits the burrow.

The exactitude with which this all plays out is nothing short of mesmerizing, but its rigor also in some ways short-circuits the comedy. Maybe Jones and Co. sensed this themselves, so that when they returned to their deconstruction of the chase three years later, they decided keep it simple: One antagonist, one target, and a setting in the American Southwest. Thus, the Road Runner and Coyote were born. And by that refinement, in defiance of logic, the comedy rose to a conceptual complexity that Fair and Worm-er couldn’t begin to dream of.

Jones has said that the Road Runner and Coyote were created out of his desire to take down the whole concept of the chase cartoon (although Fair and Worm-er suggests that he and his team were thinking along those lines long before). Nevertheless, while the debut entry, Fast and Furry-ous (1949), was meant to be a one-shot, it was greeted with such enthusiasm that the Jones crew knew they couldn’t let it go. Three years later, the second installment, Beep, Beep (1952), was released, and over the course of those subsequent cartoons, Jones the scientist would develop a set of rules under which this universe would operate. Included among the strictures: No dialogue, except for “Beep-beep!”; the Road Runner had to stick to the road; all of the Coyote’s tools had to be provided by the Acme Corporation; and, most affectingly, to quote Jones exactly, “The Coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.”

The initial run of Road Runner cartoons—with all the rules in place and the audience well-acquainted with the formula—was at its midpoint in 1957 when the newest chapter, Zoom and Bored, debuted. Everything having been firmly established, this installment had no trouble beginning in media venandi, with the Coyote displacing the opening credits as he pursues the Road Runner. But there was something different about this cartoon, something that stuck with me when—after an adolescence where I decided I’d had it with Looney Tunes and especially with Mr. Jones’ minimalist style—I rediscovered it, and realized there was more swirling about that desert terrain than initially struck both my eye and my funny bone.

At this point, we all know about cartoon physics: If you run off a cliff, you won’t actually fall until you look down; if a stick of dynamite explodes mere inches from your face, the damage is no worse than a dusting of soot and a sense of profound mortification; etc, etc. Jones himself acknowledges the tradition within his own Road Runner rules with the corollary, “Whenever possible, make gravity the Coyote’s greatest enemy.” But across the Road Runner and Coyote cartoons, Jones takes physics and pushes them to the limit, simultaneously adhering to the science while also subverting it.

In Zoom and Bored, some of the inversions can be so subtle that they feel, logically, as if they could happen in the real world: A rock loaded onto a catapult, instead of being hurled into the air once triggered, falls backwards, crushing the Coyote; a bomb meant to roll down a long, circuitous ramp instead explodes as soon as a match is touched to it.

(It should be noted that Jones also exploits the physics of comic timing in these gags, devoting considerable effort to the build up—a loving shot of the elaborately designed catapult; a long, slow camera track up the similarly elaborate ramp—before short-circuiting it all with the abrupt deployment of the punch line.)

But those short, sharp shocks serve as mere set-ups for the cartoon’s elaborate finale. In it, the Coyote deploys an “Ahab Harpoon Gun” against the Road Runner (and, really, you’d think the name of the device alone would give the dope pause). Too late, the Coyote realizes that his foot is snagged in the rope attached to the spear, and once launched, the projectile is determined to follow its trajectory with a vengeance—over cacti, under rocks, into a narrow pipe and straight through a moving truck—with the helpless Coyote dragged along in its wake. It’s the concept of inertia taken to its logical extreme, capped off when the spear plants itself in a rock wall, allowing the Coyote to pendulum down into a tunnel and the path of an oncoming train, which then propels him upward to a surprisingly graceful landing on a cliff above (and to prompt the Road Runner—seeing his traumatized adversary perched precariously on cliff’s edge and a prime target for a “Meep-meep!” that would once more launch him to his doom—into holding up a sign that reads, “I just don’t have the heart”).

And this is Jones at his precise, methodical best: Taking a concept, refining it to its pure basics, and deriving exquisite comedy out of it. And yet, it is not the thing in Zoom and Bored that has stuck with me for a near half-century. That comes much earlier in the cartoon, in a sequence that is neither as abrupt as the official throwaway gags nor as elaborate as that harpoon finale, but within its brief moment on the screen hints at something unsettlingly profound.

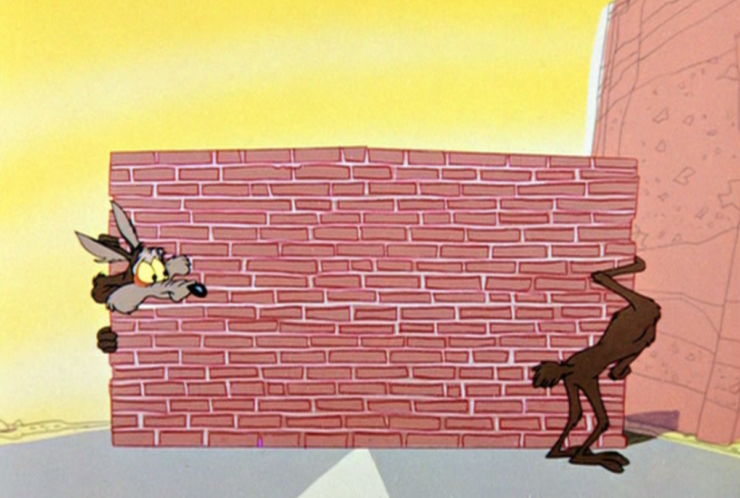

Here’s the setup: The Coyote builds a brick wall in the middle of the road. He waits on one side, hearing the Road Runner’s approach and bracing himself for the collision. And then, nothing. Confused, the Coyote approaches one end, and peers around. There’s a cut to the opposite side, and the camera pulls back to reveal that, as the Coyote’s head pokes around one edge, he discovers he’s staring at himself—specifically his ass—peering around the other. A few simple gestures and a futile attempt to catch himself confirm that, yes, he’s somehow in two places at once (and maybe, to satisfy the Firesign Theatre, not anywhere at all).

And this is what has always obsessed me from the moment I started thinking about it: What the fuck is going on behind that wall? It’s one thing to advance the notion that a harpoon is going to fly straight and true and build a comedy gold out of it; it’s another to posit some mysterious anomaly that bends space and time so one can stare directly up one’s own sphincter. (It’s also a testament to the power of storyboarding over simple writing—a thousand words couldn’t convey the premise any better than could one drawing.)

As is Jones’ nature, the sheer mind-bendingness of the gag comes down to the elegant simplicity of that wall. Elsewhere in the cartoon universe, creatures squash and stretch with aplomb. In Baby Bottleneck (1946), Daffy Duck’s leg gets stretched to approximately the length of a football field, and the animators get quite a bit of (forgive the pun) mileage out of showing him trying to run with the damn thing. But we can’t know that that’s what’s happening here; Jones puts the wall in our way, and that’s where the conceptual magic happens. In a medium where you can portray nearly anything, leaving nothing to the imagination, he obscures our sight, and leaves us to puzzle out the incongruity.

(In the wake of Rick and Morty, though, I’ve managed come up with a theory: The other side of the wall actually exists in an alt-universe, one exactly like ours, but rotated 180°. Thus when the Coyote peers around the wall, he’s not looking at himself, but at a Coyote-B, one who does exactly the same things at exactly the same time, but the other way around. We can then extrapolate from this and, observing how many times the Coyote runs around the wall, come to the conclusion that, by the end of the sequence, we are no longer watching our original Coyote, but Coyote-B. In other words, Zoom and Bored starts out in one universe, and finishes up in a completely different, parallel universe.)

(Or, alternate theory: I’ve got too much time on my hands.)

It has been well-noted that there was a distinct shift in the tone of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies once director Bob Clampett left the studio and Chuck Jones rose to fore. Originally the cartoons were hot, frenetic, anarchic. Under Jones’ watch, they became methodical and cooly cerebral… or at least as cooly cerebral as you could be while having rifles still explode in Elmer Fudd’s face. The Road Runner and Coyote cartoons may be the apotheosis of his technique: A way to strip down the narrative to its barest essentials while playing in surprisingly sophisticated ways with basic tools that form the universe. Physics may be adhered to or broken at will —whatever will provoke the most laughs—but, at least for me, Zoom and Bored stands out from the pack for the way it steers its comedy into some revelatory insights into how we observe the universe, and the way we draw conclusions from those observations. In seven minutes, it transports us from the land of the hysterical, to the realm of the philosophical.

* * *

Long, long time ago, child-me had grown frustrated with the Road Runner cartoons, with the sense that—having been weaned on Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd; Tom and Jerry; Pixie, Dixie, and Jinks the Cat—I was feeling less empathy for prey Road Runner and more for predator Coyote in his conflict with a universe dead set on thwarting him at every turn. It was only as I grew into my teens and revisited the cartoons that I realized that, yes, that’s exactly what Chuck Jones wanted me to feel; that, in defiance of the Immutable Laws of Cartoon Storytelling—chaser bad/chasee good—the Coyote was the antihero we should all be rooting for.

It took me a while to get there, but maybe you were different. Maybe you glommed onto the inversion earlier, or feel that another cartoon—Road Runner or otherwise—better sums up Chuck Jones’ distinct approach to animated storytelling. If so, hey, look below: There’s a comments section there, and it’s just waiting for your input. But, as always, keep in mind that nobody’s throwing anybody off a cliff, here. Let’s resist the urge to reach for the dynamite, and keep the conversation friendly.

Dan Persons has been knocking about the genre media beat for, oh, a good handful of years, now. He’s presently house critic for the radio show Hour of the Wolf on WBAI 99.5FM in New York, and previously was editor of Cinefantastique and Animefantastique, as well as producer of news updates for The Monster Channel. He is also founder of Anime Philadelphia, a program to encourage theatrical screenings of Japanese animation. And you should taste his One Alarm Chili! Wow!