Stephen Graham Jones is busy. In an earlier draft of this interview I included my comment that his work is challenging—by that I meant both emotionally, like all good horror is, but also that he’s so prolific he makes the rest of us who are trying to write things look like human sloths. But that’s just it—he doesn’t try to write, he treats writing as a thing he has to do, a job he’s dedicated to, and that’s resulted in 22 books over 30 years.

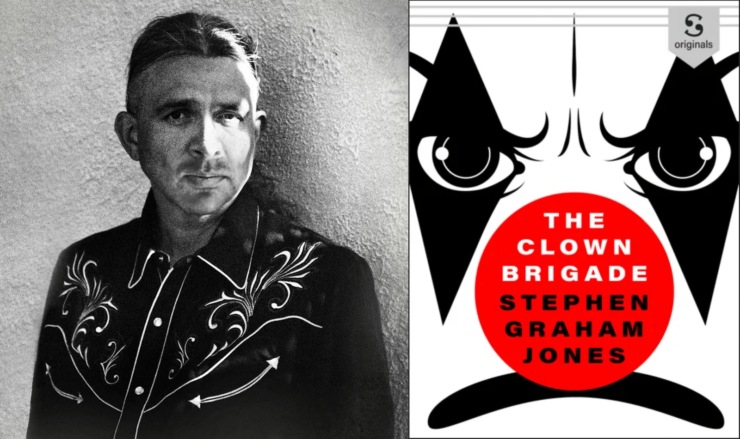

His latest? A deeply disturbing short story called “The Clown Brigade”, available exclusively on Scribd both as an ebook and as an audiobook. It was a true delight to talk with Jones about the story, the horrors of clowns, some of the real-life motivation behind Jade Daniels in My Heart Is a Chainsaw, slashers in general and Scream in particular, and Jones’ admirable writing process.

Be warned: While we did our best not to spoil “The Clown Brigade” or My Heart Is a Chainsaw, we do spoil Ari Aster’s filmography.

Leah Schnelbach: I always like to start with some background: how did you get started as a writer?

Stephen Graham Jones: I came through school—I was a philosophy major, and then at the very end I became a creative writing major…and then I went to a PhD program and wrote a novel for my dissertation. I got that novel published, picked up an agent, and that novel came out in 2000. My first story was in an interdepartmental ‘zine—you know, a little pamphlet with staples and everything. (laughs) I think that was probably ‘94. But my first national publication was in Black Warrior Review in ’96…and in the last 22 years I’ve probably done around 30 books…mostly horror.

LS: What was the inception point for horror? Was it film or stories?

SGJ: You know, I wonder if it was Ray Bradbury’s story “The Veldt”—I read that young, in elementary, and it’s always stayed with me. I go back and read it every once in a while, just to remember who I am and what I’m doing. That might be when that bug bit me.

LS: I think a lot of conversation around horror specifically is always about protecting kids, and feeling like kids aren’t actually old enough for horror, but every person I know that actually is into horror got into it so much earlier than anyone thinks.

SGJ: But I wonder, people who are against giving horror to kids probably use all of us who encountered The Exorcist or Chainsaw Massacre or “The Veldt”, or whatever, too young—they’re like “See? It messed you up. Now, you’re messed up for the rest of your life” you know?

LS: Yeah, but I’d rather be messed up the way that I am.

SGJ: But really I mean, with kids—they’re small and powerless in the world. They don’t know why things are happening. They’re told what to do, they’re not giving any explanation for why they’re doing this, and everyone is a towering monster to them, you know? And adults are capriciously violent. I think kids live in a world that is really primed for horror. But Horror stories allow them to understand that sometimes you can beat the monsters, you know?

LS: Exactly. I read in an interview you gave, talking about how humans are hardwired for horror because of our years on the savannah being bags of meat.

SGJ: Yeah!

LS: And you’re right, kids are kind of still in the “bag of meat” realm until they’re older, with that sort of vulnerability. And I do think a lot of adults, somehow, forget that.

SGJ: They do.

LS: Who would you say were your biggest influences–in horror writing, and just writing in general, as a kid—a student—versus now.

SGJ: I think the first writer whose work I read all of it was Louis L’Amour, when I was 11 or 12—I loved, and I still love, westerns. Very soon after I found Conan the Barbarian, and I didn’t understand that Conan was Robert Howard. I thought it was just a character that everybody wrote. I found Tommyknockers when I was…16, I guess? I loved Tommyknockers…I still like Tommyknockers a lot—then of course, I fell into the rest of King. As far as like, beginning out writing, those were probably some of my prime influences.

But then in my early 20s, I stumbled into two people who would probably change my writing career…well, three. Um, maybe four, actually? Louise Erdrich: her novel, Love Medicine, and the first four in that series, is it Bingo Palace, Tracks, and…The Beet Queen? That’s a wonderful little four book, like, quadrilogy. I just love her writing so much. And also Philip K Dick, I fell into. I’m so thankful to this one fellow grad student at North Texas in Denton, Texas who introduced me to PKD, gave me VALIS, I think it was, and I inhaled VALIS and then I went back and read every PKD I could. Behind me here (gestures to prodigious bookshelf) I’ve got so many Philip K. Dick books and actually, somebody just give me a new PKD! (shows me) I Am Alive and You Are Dead: a Journey into the Mind of Philip K Dick.

LS: Oooh!

SGJ: He’s been a huge influence. And Thomas Pynchon, really I discovered Pynchon and Gerald Vizenor at the same time and they’re both really, really dense stylistically, syntactically, just like narratively. Philip K. Dick had that narrative kind of nesting, you know? You never know what level of reality you’re in? And Pynchon and Vizenor were doing similar things, but in different ways, and I was really fascinated with that. So I spent six, seven years, just completely lost in that kind of stuff. I had to read all the hard books, you know. I remember in one two-week period I read Pynchon’s Mason & Dixonand David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest…and I don’t think I could do that anymore.

LS: I love those as a one-two punch.

SGJ: Around 2002, I guess I had one or two books out? And I was on a panel with Joe Lansdale in Austin. I hadn’t read him yet, and we ended up on a Conan the Barbarian panel, actually, at the Texas Book Festival. And so our panel talked about Conan and then we get to the Q&A period at the end, there’s 80, 100 people out there and one of them raises their hand and says “Joe, what genre do you write in?” and without skipping a beat Joe Lansdale says, “I write in the Joe R. Lansdale genre” and I was like, “All right!” That changed the course of my writer self, because I’m like: that is what I want. I don’t want to just be this type of writer, or that type of writer. I want my name to be the genre or… I want license to write whatever I want to write. I want it to be about the quality of the story and the quality of the writing—not the content.

LS: That’s fantastic. Because that was—I was surprised reading “The Clown Brigade” because it is definitely horror of a kind, but it’s a very different tone to it. And I really…I’ll skip ahead to that question actually: why clowns? Because you’ve dealt with so many—you’ve had people with chainsaws, you’ve had elks, you’ve had lake ghosts—so why was the clown imagery the one that you went with to bring in surrealism?

SGJ: I knew this would be an urban story. Like one hamster in a big maze of buildings and tunnels, so, I had to ask myself—what’s gonna be the most unsettling thing to see forty feet away through a crowd, for a moment? There’s a lot of things that can be terrifying, I mean a werewolf is going to be terrifying in any context, and a vampire, you’re not always gonna recognize a vampire, depending what type you’re messing with. But I decided that a clown, to me, was the most off-putting—for all the reasons that we always have clowns in horror, because the outsides, presumably, don’t match the insides. They’ve got this cheery appearance, but a corrupt interior of some sort. These clowns, particularly, I liked the way that they settled into this story as initially, maybe there, but maybe not there. To me, “maybe/maybe not” is one of the main axes or cruxes of horror—the longer you can kind of dilate that moment, I think, the more pleasurable experience it is for the horror audience.

LS: Definitely! Because I really loved how the first one that you see…I don’t want to spoil too much, but I really loved the first one that you see is completely: “Oh this might just be somebody going to a party and put their makeup on early”, and then the further you go, the makeup itself becomes so much more, just gross and awful and awesome.

SGJ: I wonder if I was working…you know, I don’t know if you’ve seen them, there’s those two clown horror movies, Stitches, and Clown. I love those two movies. And I guess after I wrote “Clown Brigade”, this is probably just two weeks ago, I finally watched Terrifier 2. And that’s everything it promises to be, you know.

LS: I haven’t watched it yet! I have to be in the right mood, and I keep seeing people talking about literally throwing up during them, which, nothing bothers me? So, I can’t imagine that this will. But maybe I should test that.

SGJ: I’m pretty squeamish, and I can’t really handle gore all that well for a horror person. There were I think two places in Terrifier—I was at the theater—where I didn’t cover my eyes, but I kind of blurred my eyes, a little. Like I don’t want this popping into my head at 2:00 in the morning.

LS: No, that is the one thing, every once in a while…you’ve seen Hereditary? Like that was the one, the head on the attic door. That came back at 2am once. And obviously it’s not anything logical, it’s just upsetting emotionally.

SGJ: But, exactly, I think horror is under no compulsion to be logical, you know? To tell you the truth I feel like what happens a lot of times is somebody writes a perfectly good horror story or novella or novel, and then they revise it, either by themselves, or with an editor or friends, they revise it for like a year or two years. They figure out the rules of this world, that when you pull this lever, that light comes on over there, or when you pull this handle, that door opens, and what’s happening is, they figured out the system of this world and that makes the world more real. But it also shades this horror story, which was perfectly fine, away from horror. It becomes dark fantasy. It becomes a story that makes sense, with horror imagery.

LS: Yeah!

SGJ: And that’s not quite a scary to me. It’s still it’s a fun ride, but it doesn’t lay a dark egg in my head that’s gonna hatch at 2:00 in the morning.

LS: Yeah, exactly. I’m looking for that all the time, because obviously, the more that you watch or read, the more you can kind of pick out like “Oh this is when this is going to happen” or whatever. So it’s been nice whenever I’ve finished something, like Hereditary, that just short circuits all of that.

SGJ: Well it seems like what Ari Aster is doing is, at least with Hereditary and Midsommar, he’s messing with our expectations by putting the key, terrible terrible thing early, and then it’s like a ramp down from that for the rest. Which is a weird way to build it, because usually you’re on a slow on ramp up to the worst thing possible, you know, but like in Midsommar, we start with the parents getting carbon monoxided, and that’s a wonderfully put-together sequence, and to me anyways that’s a high point. And it’s almost like we’re those old people falling off the cliff for the rest of the movie.

LS: I always ask this, but whatever, I feel like our readers really like, and I like, getting sort of a rundown of your process, day by day? If there is a daily process to your writing.

SGJ: Pretty much my days are wake up, go to the airport, go to a different town.

(laughter)

LS: Which isn’t that conducive to writing though?

SGJ: I’ve had to train myself to have no writing rituals because when you have writing rituals, like I’ve got to have the blinds twisted this much, I gotta have this candle, that glass of wine, and the dog has to be over here…all the stuff you do? That’s great if it promotes your writing. However, you’re just kind of arming yourself with excuses not to write, you know? Over the last couple of decades I’ve had to train myself to write on trains, in hotel lobbies, and especially on airplanes. The last two, two-and-a-half, three weeks? I’ve been on the road nearly every single day, and I think I’ve written…what is it? Three stories, one comic script, and an essay. Just because I have to. It’s not about “Do I have time?” It’s about “I’ve got to do it”, you know?

Whenever I have like a week free for some odd reason. and can write all the time, I still won’t write all the time. I’ll probably write five hours of the day, but I’m always out doing my mountain bike or shooting pool or going to movies or just, doing life stuff, you know? If you only only write, I think you kind of go a little bit crazy. You’ve got to do other things. I’ve discovered over the years that I can’t write for more than 90 minutes at a time and still produce usable stuff. I can write for 10 hours at a stretch, no problem—but eight-and-a-half hours of that is going to be stuff I have to erase. My brain is good for about 90 minutes at a time, and then I have to go out and do something with my hands and reset.

LS: But in order to write like that, what sort of mental armor have you built?

SGJ: Probably it’s playlists, actually. I figured out a long, long time ago, and I figured this out because our house was so small that my desk would be in a corner of the bedroom—everything at once, you know? So I’d just put headphones on, and I discovered that if I can make like an 80-or 90-minute playlist for each novel, then only listen to it in that order, from Song #1 to like Song #18 or whatever, and only listen to it when I’m writing, then after about a week and a half of that, I get conditioned such that when I hear the opening beat of whatever that first song is, it emotionally drops me into the story space of that novel. I don’t have to warm up—I’m just there. And it’s really, really wonderful. So, if I have a headspace, it has a lot of Cher, Meatloaf kind of music playing in it.

LS: That’s really good though! What was the playlist for “Clown Brigade”?

SGJ: I didn’t have one—for stories, I don’t do playlists.

LS: Oh, they’re for novels?

SGJ: Yeah, just for novels….well, I do remember the playlist I listened to while I was writing “Clown Brigade”…it’s just ‘70s rock if I remember correctly. It’s kind of like an “etcetera” playlist, it’s what I listen to when I’m doing work, but I’m not doing a specific project, if that makes sense?

LS: But it’s still sort of tricking your brain.

SGJ: Yeah, it is.

LS: That’s a really good idea. I might have to start doing that.

SGJ: But I shuffle it so it’s not the same order, so it’s never dropped me into like the same emotional place. It’s just like, I think music as far as my process in writing, music is helpful like what I said: because it drives me to the emotional story space. But it’s also helpful because it distracts or keeps occupied that critical part of my mind, which is always going to be second guessing what I’m doing and telling me I’m not good enough. Because—I don’t believe in writer’s block. People always talk about it and I think it’s just some like, tragic pose that people adopt. I mean I do understand that people hit a wall on a project and can’t move forward, but I guess the question I ask is: do waiters get waiters block? Do plumbers get plumbers block? And they do, they wake up in the morning, and they’re like, “I don’t want to do this today”—but they go in anyway. And that’s what you do as a writer. You go to work anyway. You do the work. It’s not about whether you want to, it’s about whether this is what you do, and who you are.

When people say they have writer’s block, I always think what they really have is too many people looking over their shoulders. Too many imaginary people like, the critical establishment, the 200 years of history that’s going to come to this story, and their peers, and the people they’re challenging with their own writing. Like, if you have too many people looking over your shoulder watching you write, it is really hard to get anything down. I always say just write like you’re writing for your 16-year-old cousin who’s stoned like 30 hours out of every day and he’s gonna laugh at everything you say—everything you say is golden. If you can run with that, you can get a lot down and then you can come back and fix it! But like Harlan Coben says: “You can’t fix no pages”.

LS: I might steal that too. My other kind of hardcore craft question…well I have two. I don’t know if they’re actually answerable—in my own work I don’t think I’d be able to answer them—but how do you—your characters jump through a lot of different points of view. How do you settle into different points of view? Do you have a process of getting into them and writing through them?

SGJ: You’re right, that is a really tricky question to try to answer.

LS: And I can’t! That’s why I ask other people.

SGJ: But it’s good to try to wrangle with that. I think for me…I know some writers do it differently, some writers, before they set pen to paper in their story world, they do a little character exercise where they know what their character’s 12th grade birthday party was like, they know the mean thing their mom said to them when they were 15, they know how graduation went when they graduated high school, they know ten or twelve key points of this character’s life, and they can like flesh out these bullet points and have a whole round, deep person. I’ve never done that—I’m terrified of doing that for some reason. I’m not really sure why. But I think the reason I’m terrified of it, actually, is that I see character as a product of story. So, when I think of a story idea it’s never: “A character who witnessed something when they were 4 is now going to be triggered back into that when they’re 25.” Which is what really happens, we all live that life, of course. But what I think is: “You’ve wrecked your car. You’re upside down in a creek. What do you do?” And then once I’m inside that car upside-down with that character, that character starts to become real, and the character is an expression of the story. And I think that’s why each character, each point of view, is maybe different in my work. Because each situation is different, so it expresses a different person out of it.

I remember when I was in doing my PhD work at Florida State,…like back then the first question you got asked in any writer circle you broached into was: “Are you plot or are you character?” I don’t know why that was such a question back then—it’s such a binary thing, you know? And I don’t think it’s really either/or. But I would always come down firmly that “I’m plot”. And I think if you asked me today, like, 30 years later, I probably am still more plot than character. But at the same time, I completely agree with Stephen King that nobody cares what terrible things happen to the people in your stories if the people are fake. You gotta have real people—especially in horror. You can’t just prop up carving dummies for the chainsaw to come at. People with regrets, desires, histories, pasts—real people. If the reader can’t invest in the outcome of this, whether they’re rooting against or for the character doesn’t really matter—you want to have them invested intellectually and emotionally and probably with their senses too. Then you’re doing something. Then it doesn’t have to be a chainsaw, It can be somebody coming in with a safety pin.

LS: Building on that, how do you write a terrifying, upsetting scene? How do you block it out and think through it? And have you ever actually—because you just said you’re squeamish when you watch things—have you ever like, squeamed yourself?

SGJ: Oh, definitely. I think the two times I’ve done it…I did a novel called The Least of My Scars about a kind of a bad dude who gets abducted by a crime boss and locked in an apartment. And he has to kill everybody that the crime boss sends to his door.

LS: Ooh.

SJ: He’s able to just live in a fantasy world and do the worst things. I wrote that in 2008, I think it was, and I just had two books come out in 2007 and I didn’t have any books coming up in ’08. I don’t think any books come out in ’09 either. So, like if there’s ever been like a dip or a quiet part in my career, it’s ‘08 and ‘09. I was actually kind of despondent—I mean, I’d done like eight or ten books at the time, but…is this it? Is my career over? But I was kind of in a, I don’t know, a bitter place. When I wrote Least of My Scars, what I wanted to do with it was see how dark I could get. What are the edges of what I can tolerate, or what I can do—and then I wanted to go a bit further. Because I think it’s always important to push yourself as a writer. I think I lost twenty pounds over the six weeks of writing that book. Just every time I sat down, I was physically ill because it gets pretty dark….but I remember in, I don’t know why I keep going back to Florida State, but I was in Janet Burroway’s writing workshop, and she had us do a kind of exercise one day where she was getting us to define our own set of narrative ethics. And I don’t remember all of the bullet point questions she asked us but one of them was: what is one thing your character would never do? That kind of interested me. What is the line I won’t cross as a writer?

LS: That was actually my next question! Is anyone off limits? Like are you going to not kill the baby?

SGJ: Yeah! I thought about that a long time and I finally realized that the most sacred thing to me is motherhood, you know? I see this in my books over and over. One of the things that always happens is a mom like steps in front of something to protect her child. I love that so much, but I was asking myself How can I pervert that? And so in Demon Theory, I have a 14-year-old character, Hale. He’s in the fruit cellar outside—not like a basement, it’s like a cellar over to the side of the house. And he’s up on a stool with a noose around his neck and he steps off that stool, and he jerks, and he starts to hang? Right when his mother comes down those stairs. And…she sees him and she runs over to him and she grabs him around the legs, but instead of lifting him up she pulls him down.

(laughter)

And that was the worst thing. That was the worst thing I could think of. I wrote that book in 1999 and I think I’d done that exercise with Janet Burroway in 1998. That’s as far as I could go. But with horror, like, if I’m not getting scared when I’m writing it, then I’ll quit writing it. Because there’s no reason. Scares are not mechanical things, scares are emotional things that I’m trying to foist off on the world. It’s like I have that VHS tape in The Ring and I’m like, “Here you watch this!” I used to think that I could give my nightmares away and sleep better, but to tell you truth, all that happens is they get higher definition and they’re more real to me, and people talk to me about them.

(laughter)

Buy the Book

My Heart is a Chainsaw

LS: Another interview that I read with you were talking about My Heart is a Chainsaw being emotionally autobiographical. I was wondering if you could talk about that? Because it felt somewhat autobiographical for me, reading it.

SGJ: No it is: Jade is an outsider, you know, doesn’t fit with her family. She doesn’t fit with her classmates. She doesn’t fit with her community and she just doesn’t plug into the world, but she wants to so badly. She would never admit it to anyone, but she wants to be part of things, you know? And I don’t think I’m special in this regard at all, but I think writers, something about the way that we process information makes us, like at a party, we’re often not actually in the party. We’re kind of at a remove from the party, watching the dynamics, so that maybe we can write it down later and make it good. Like we don’t engage the moment enough. It feels like we’re always like mentally cribbing down lines, and all that and I wish I could just be at the party sometimes, you know?

But with Jade, so many of the things she goes through are things I went through. She talks about always getting sent home from school for her T-shirts and those T-shirts she’s wearing are T-shirts I was wearing and getting sent home for. And I was always getting picked on by the principals, vice principals, by police officers…anybody in authority always wanted to throw me up against the wall or kick me out of school or just…do all that stuff, you know? And I was also always changing my hair. When I was 12, I decided it was too weird being Indian in West Texas because I was the only Blackfeet—I mean, I had some cousins who weren’t in in my county, and my dad was off in the Air Force—so it was just me. And it seemed like everyone I walked into were like “You’re weird! What’s up with you?” And like, “I just want to be a person, please?” So, I decided I was gonna be Italian instead of Indian, so I went and got a perm, and it wrecked my hair forever. And then I decided to have a skunk stripe in the middle of my hair just because that’s a really wonderful way to make yourself part of society in West Texas…

LS: I love that!

SGJ: But and then, this is two, three years later, I fell in love with Def Leppard and so my clothes were black and slashed everywhere, and I was always having battles with rattlesnakes and leaving with their skins and rattles. And I got to where I could make earrings from rattlesnake rattles, so I was always wearing rattlesnake-rattle earrings [nb: I don’t care what the citizens of West Texas had to say: this is cool as shit] and I was I was also a night janitor at a daycare and the owner’s rule was I couldn’t wear my rattlesnake rattle earrings.

LS: I was also a high school janitor! But yeah, it’s like, at night! Who cares what you wear?

SGJ: Also at this daycare, it was the biggest daycare in Texas at the time, and of course there were clowns painted on every wall. You know, every corner you walked around there’s a nine-foot clown. After one night at I went to a friend and borrowed a pistol and carried a pistol for that job because I was terrified,…it was just so startling. One of my duties there was to go out in the night and rake the gravel in the playground level again for the new day, and one night about 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning, I go out there and I’m raking the gravel level, and there’s a big like eight-foot-tall cinder block fence all around the playground so kids can’t get out and people can’t look in. And right on top of the gravel is a big old, like, a folding knife? But it’s about 10, 12 inches long and it’s got blood all over the blade. So I’m pretty sure what happened was someone was running from the cops on the other side of that fence and they tossed their weapon. And I took it home—I’ve still got it in the garage. It’s a pretty good knife.

LS: So…you kind of walked into part of a horror story.

SGJ: Yeah! But the real horror story on that job was the potty training room, which was like an eight-by-fourteen room that was tiled,…the ceiling, floor, walls, everything was tiled, and all these miniature, like six miniature toilets on each side, like little bitty toilets, and there were pretty serious indecencies in that room every night.

LS: You were very primed to write horror.

SGJ: Yeah. I mean, it was great. I think I was like saving up pieces of Jade [from My Heart is a Chainsaw] inside me to write down someday.

LS: Yeah! And there is there’s a sequel coming?

SGJ: Yeah, and a third one as well. I’ve already written the third one.

LS: Good. Because I was, um, a little frustrated by where it stopped, in a good way—it was very much like “Here???!!! What???”

SGJ: Oh, you know, I remember when Chainsaw came out, like, some of some of the reviews were like, “This is fun and all, but the character doesn’t arc or develop” and that’s right, of course, but we hadn’t announced at the time that it was a trilogy, and when you’re doing a series character generally arc over the series instead of arcing over the individual installment…

LS: Yeah, but I feel I felt like she did? Like quite a bit.

SGJ: Yeah, I think she grows! But it’s really fun where she goes in the second one, I think. But I guess I’m not supposed to talk about that.

LS: Oh, yeah, no spoilers. Cool! Oh, so while we’re talking about [Chainsaw] what are your top slashers or… well horror in general, but then for slashers, what are a couple that are in your pantheon?

SGJ: The pantheon for me, I mean, the slasher characters are of course: Michael and Jason and Freddy. But my favorite slasher is Scream. I know it feels like a generic answer, but man, when I saw Scream in ‘96, it’s like all the homework I’ve been doing all my life was suddenly—this was the test, you know? And I could pass this test, and it was wonderful. I still read and watch and read everything about Scream. I’ll probably never be done with that movie, I suspect.

And as far as top horror, that’s the trickier question. I already mentioned this movie: one of the better movies, or a movie that does exactly what it’s supposed to do is The Ring, either the American version or the Japanese—they’re both good. And I think what’s magic about that movie is that it keeps on changing, kind of like the way “Bohemian Rhapsody” has all these different movements in it? I feel like The Ring has those different movements in it. And I guess The Conjuring came along, it did a similar thing, where it was kind of processing through what felt like different genres, you know? I really appreciate that. And I actually did that in my novel Demon Theory—it’s in three parts. The first is a slasher, the second is a monster story, and the third is a haunted house, and I love processing through that a whole lot like that, you know? But that’s been out of print for forever. I think it might still be available digitally, but it’s got like…400-odd footnotes, and digitally, 400-odd footnotes can get tricky.

LS: Speaking of Scream…I recently also read Head Full of Ghosts and…then obviously reading Chainsaw, I was wondering how you balance discussing media in the book? Or do you think about a balance as you go? Because obviously, with Chainsaw, you had Jade’s essays dotted through, which I thought was a really cool way to do it. But did you think through, like “How many references are too many?” Or is there such a thing as too many?

SGJ: No, yeah, that’s a good question. Um, like I was talking about Demon Theory—in Demon Theory, I did that with footnotes. Not every slasher movie is mentioned in the footnotes, but that’s the way I’ve done it there. And then…Demon Theory was ‘06. In 2012, I think, I had The Last Final Girl come out, which is a slasher, but I just, I decided to not allow myself footnotes, but I still wanted the characters and the story to be dragging behind the history of all these slashers, because I always think … it’s so fakey to me, like, in a zombie movie that the characters have never seen a zombie movie. And so there’s always just like long expository arc, like, “Uh-oh, is that a dead person walking around? What’s going on? It’s too weird!” And we’re all bored in the audience like “It’s a zombie! Just shoot it in the head and move on!” And I think what Scream did was—it wasn’t the first one to do this, but it was probably the biggest one to do it—it made the characters aware of the video shelf that was in play at the time, and that move changed slashers forever more. And I always want to do that too. I wanted my characters that exist in our world because that has more capacity to scare us, if it’s where we live. So, in Demon Theory I did it with footnotes and in Last Final Girl I moved the footnotes up into the text, where the character Izzy and her friend Brittany are always talking slashers. I wanted to dramatize it instead of bury it in footnotes. And that was a fun way to do it, but then I thought there’s gotta be another way. So, with My Heart is a Chainsaw, I did it with essays and kind of with Jade’s interior monologue that’s always burbling—she sees things through slasher goggles. That definitely colors her world, washes it red. And actually, I found another way to do it with an upcoming novel I have called I Was a Teenage Slasher—I found a different way to do it that never mentions a movie title. So, maybe there’s more ways to do it, too. I don’t know. I can’t think of any right now, but there’s probably got to be.

LS: OK, I had one older completely indulgent question…which is that in another interview you mentioned Strange Stories and Amazing Facts, which rewrote my brain when I was a little kid.

SGJ: Me too.

LS: Are there any stories from that that you’re going to draw on in your writing?

SGJ: You know, one of those little entries is at the core—it’s the kernel of Demon Theory actually. A little kid named Oliver Larks back in, I don’t know, probably 80, 100 years ago is walking out from his house to get water at the well, in the snow, in the winter, in Ohio or Illinois, somewhere like that. And suddenly—he’s gone. And they follow his footprints and they just stop halfway to the well.

LS: Oooh.

SGJ: And that I have never gotten over the trauma of that, you know? Because I grew up in West Texas and it’s all sky. I was always afraid, if I was ever walking in a place where no one could lay eyes on me, then there was no reason for the sky not to suck me up, you know? Like in Nope or something. And Strange Stories and Amazing Facts. When I remember fifth and sixth grade, I had so many nights where I wouldn’t sleep at all, because I would open that book again, and I would be so terrified, I had to keep reading, you know? I’d go to school exhausted. And when I could sleep, the way I would sleep was: if I kept that book beside me in bed and kept my hand on it, that would keep it closed so nothing would come out and get me. I’ve got two copies of that book now and I’ve also talked to Jill Essbaum, the poet and novelist, and Kelly Link, and they’re both—that book is also fundamental to them, you know? I wonder if we need like a support group for all of us who were traumatized by that as kids.

Buy the Book

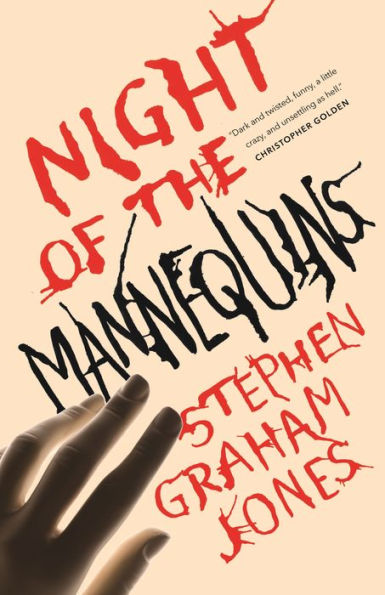

Night of the Mannequins

LS: I need it again! My copy was destroyed in a flood….or was it? Eventually I need to get another copy

SGJ: Yeah, maybe it’ll be like the Jumanji game. It’ll wash back up.

LS: Exactly. It’ll just be on the doorstep. (laughter) Our time is just about up, do you want to tell us about what projects you have in the works?

SGJ: Number Three of Earthdivers is coming up in early December—it’s so fun doing a monthly comic. And “Clown Brigade”—you can read it on a device, on the site, but there’s also the audio! They did a really killer audio of it. I read my own Acknowledgments, the Author’s Note thing.

But “Clown Brigade” made me nervous. Just, where it ends where it ends up and kind of Kyle’s dynamic, his mental state. Um, I mean, I never want to like stigmatize mental health, you know? But, um, Kyle does have some issues, and I don’t think his issues are organic, I think his issues are reactionary. But yeah, where the story ends up made me very nervous. I don’t want to sensationalize what happens, you know? And that’s why it’s called “Clown Brigade”—I wanted to build the story such that bad actors could not use it as a banner. That they wouldn’t feel validated by it. But yeah, this was, it was a very nerve-wracking story. It was a fun story to write, but it was nerve-wracking story to publish, if that makes sense.

LS: As a reader, I certainly didn’t come away feeling like he was like the hero of the story, as much as he was the protagonist in the story, cause I liked how you sort of shaded in—again I don’t want to spoil the story—but the way that you sort of shaded in what’s actually going on so that you start to see more and more what the reality is versus his perception of the reality.

SGJ: I wanted to lock the readers into his perception such that they couldn’t see the truth, which is just outside of his line of sight.

LS: Yeah. And then just the body horror of the final scenes. so good Because again, I am not squeamish. So I was like, giggling reading that because [redacted for spoilers]…it’s just, gorgeous.

SGJ: …my face felt weird when I was writing it!

LS: It comes through. Because like, you’re really describing how everything is how it’s impacting him, even through his haze of mania.

SGJ: Yeah, he is in a manic state. He was like—in horror I’m usually writing from within or beside the hero, like you’re talking about, but in this case…it’s not that he’s an anti-hero, he’s something different, he’s malignant. It’s never comfortable when I’m on the side of…like those other two books I mentioned that unsettled me, Interstate Love Affair [included in Three Miles Past] and Least of my Scars, those are also stories where I’m walking in lockstep with somebody with seething, bad, dark stuff in their head. But I think, as a writer, you’ve got to go to those dark places… as a horror writer, you’ve got to engage that. If you don’t, then I don’t think you’re being honest.