The story of how I came to write Origins of the Wheel of Time begins with my first reading of Robert Jordan’s The Eye of the World as a lad, not long after it came out. I didn’t see the whole picture at that point, but it was enough to have an inkling that there was a bigger story behind the story of the Wheel.

Early on in the Two Rivers, for instance, we meet Thom Merrilin the gleeman. After he starts telling the kids about the stories he can tell, including “Tales of Artur Paendrag Tanreall,” Egwene asks him to tell a story about Lenn, who “flew to the moon in the belly of an eagle made of fire,” and “his daughter Salya walking among the stars.”

“Old stories, those,” Thom Merrilin said, and abruptly he was juggling three colored balls with each hand. “Stories from the Age before the Age of Legends, some say. Perhaps even older. But I have all stories, mind you now, of Ages that were and will be. Ages when men ruled the heavens and the stars, and Ages when man roamed as brother to the animals. Ages of wonder, and Ages of horror. Ages ended by fire raining from the skies, and Ages doomed by snow and ice covering land and sea. I have all stories, and I will tell all stories. Tales of Mosk the Giant, with his Lance of Fire that could reach around the world, and his wars with Alsbet, the Queen of All. Tales of Materese the Healer, Mother of the Wondrous Ind.”

Here, the characters are referencing our history—King Arthur, John Glenn, Sally Ride, Moscow’s intercontinental ballistic missiles, Queen Elizabeth, and Mother Theresa—through the half-remembered haze of their own past. Over the years, I realized more and more how integral this process was to the formation of Jordan’s work.

So when it came to writing Origins, one of my many goals was to see how far back this process went. Was this part of Jordan’s original conception or something that was added in organically? And, most importantly, exactly how was he doing it?

Helping to answer these questions was the fact that Jordan was something of a hoarder.

No, I don’t meant that he was a hoarder of random detritus. As busy and full of things as his offices were, they weren’t piled up with the disgusting and disturbing junk that you’d see on a reality television program.

Instead, he was a hoarder of words.

It you don’t know, the Wheel of Time series of books contains some 14 million such words, but the materials that Jordan used to compose them are far, far more numerous. And, word-hoarder that he was, he saved an extraordinary amount of these materials. This. Is. Awesome.

Most (but not all) of these notes are now in the care of the Special Collections of the Addlestone Library at the College of Charleston, donated by his beloved wife and editor, Harriet. They are Manuscript 0197 in the catalog, a shelf title that constitutes the entirety of the James O. Rigney Jr papers. I refer to them, collectively, as the Rigney Papers.

I’ve visited the Rigney Papers a fair bit: writing Origins meant investigating deep into the notes that Jordan left behind in order to answer the most profound questions about how this monumental work came to be. And most (but not all) of those notes, as I’ve said, are there.

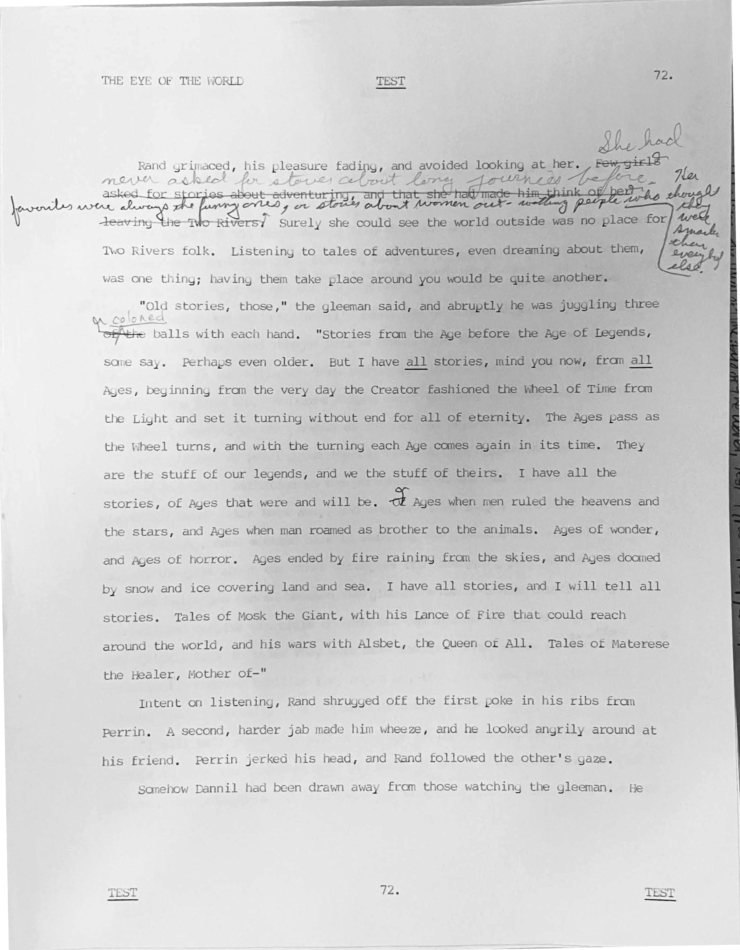

As but one example, we have Jordan’s earliest (more or less) complete draft of The Eye of the World: the “Test Manuscript,” as Jordan labeled it (and from which I provide some extensive quotes in the book). On pages 71 and 72 we can see Thom’s exchange with Egwene and the other kids, the one that led to that bit I just quoted.

There are some differences. Artur, in this early draft, was “Artur Calwyn Adnaren,” and Egwene asks for her Lenn and his daughter Salya as titles of stories rather than subjects of them. As for Thom’s speech, it’s a bit longer than that which would appear in the final book:

“Old stories, those,” the gleeman said, and abruptly he was juggling three colored balls with each hand. “Stories from the Age before the Age of Legends, some say. Perhaps even older. But I have all stories, mind you now, from all Ages, beginning from the very day the Creator fashioned the Wheel of Time from the Light and set it turning without end for all eternity. The Ages pass as the Wheel turns, and with the turning each Age comes again in its time. They are the stuff of our legends, and we the stuff of theirs. I have all the stories, of Ages that were and will be. Ages when men ruled the heavens and the stars, and Ages when man roamed as brother to the animals. Ages of wonder, and Ages of horror. Ages ended by fire raining from the skies, and Ages doomed by snow and ice covering land and sea. I have all stories, and I will tell all stories. Tales of Mosk the Giant, with his Lance of Fire that could reach around the world, and his wars with Alsbet, the Queen of All. Tales of Materese the Healer, Mother of—”

For my purposes, the references to our history are all there, which is great. And there are far earlier materials than this—we have scraps of Jordan’s very first thoughts, which I include in Origins—showing just how far back this referencing work went. That’s really cool to see, as are the subtle changes, like Artur’s early name or the fact that Jordan decided a bit more information might be needed for the reader to understand that Materese was Mother Theresa.

They might seem like little things, but these details in the Rigney Papers are an endless gold-mine for a researcher like me.

They require a lot context to understand, it should be said. I talk about this more in Origins, but the simple fact is that Jordan could change his mind on things (sometimes big things!) without throwing away the old notes. Without understanding his writing process and the bigger picture we’ve built of how he worked, it can be far too easy (and even tempting) to get confused about what you’re seeing and the importance of it.

One thing that I’m saying, I suppose, is that I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to access the notes just to say you’ve done it or something like that. These are truly precious and irreplaceable items. The library is not a place of pilgrimage. Visiting them shouldn’t be a feather in a cap. Our common interest should be to ensure that they aren’t locked away and that they remain available for dedicated research.

All that said, the papers that are publicly available are publicly available so that they can be used by dedicated researchers. So for anyone truly needing to use them for a specific purpose (or those just curious to hear what it’s like), I thought I’d share with you what it’s like to visit the Rigney Papers.

To start with, if you’ve never visited an archive before, you may need to temper your expectations. The Special Collections at Addlestone Library houses a lot more than just the Rigney Papers. Don’t go in expecting a fan gathering or Wheel of Time nirvana. It’s a quiet, working research library that receives far more visitors for its extensive archives of material on the early history of South Carolina than it does for the Rigney Papers. Dress professional and act professional.

Part of being professional means following the rules. It’s fairly typical of an archive, for instance, that you’ll be subject to a basic principle of non-disclosure to look at the holdings. For instance, I’d love to tell you what I found handwritten on the back of an envelope in the Tolkien Archive at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, but the Tolkien Estate said I can’t … so all you can get from me is this teasing reference to the fact that I know something really important that a lot of folks have wondered about a certain someone in the Lord of the Rings and it’s quite clear but if I go any further the lawyers will come for me …so sorry.

A similar basic non-disclosure rule also governs the Rigney Papers that are available for public viewing. You’ll need a pre-existing appointment to visit the archive, and then you’ll need permissions from the Estate to take any pictures of the papers or to share anything you see within them. I realize this might stand in the way of you getting some fandom cred or website hits by boasting of the secrets you think you’ve discovered, but rules are rules. And if you want these kinds of materials to continue to be available to us all—which you should!—then you need to follow the rules. Again, be professional.

Once you’ve gained entry into the Special Collections and signed whatever needs to be signed, you’ll be assigned a table in the Reading Room. This will be your working space, and you don’t leave it except to go to the bathroom or lunch.

Again, like any archive, the key thing is to follow the rules. Some archives will forbid the use of electronics. Most forbid food or drink because obviously. When I’m working in an archive I don’t have an ink pen within ten yards of my person. Some archivists might murder you for that kind of thing. (Maybe not literally. Maybe.) Everything about being in an archive is about leaving things exactly as you found them.

It’s called a Reading Room because it’s where you read materials. It’s not the place where these materials are stored. The things you’re really after are kept separately in a more secure and climate-controlled space and you don’t get to go in there yourself. Authorized personnel only.

As to that, you should also prepare yourself for what a special collections usually has. Yes, there will be some material artifacts, but for the most part an archive will be a bunch of boxes filled with papers. These boxes may (or may not) be the result of an attempt to organize the papers they contain: by date, by subject, or by something else entirely. When it comes to the Rigney Papers, you can see from the online catalog (more on that in a moment) that there are boxes centered on drafts of books in the series, as well as boxes centered on correspondence or notes from a certain time period.

So, with your workspace prepared, you’ll need to order up one of those boxes to read. Usually, this involves filling out a call slip that you hand to the person on duty. In clear and legible writing, you provide as much information as possible. In the case of the Rigney Papers, this means you tell them the manuscript number and the box number.

Buy the Book

Origins of the The Wheel of Time

You can’t, in other words, just ask to see all the Rigney Papers, because there are a lot of boxes.

This means you’ll need to have a plan.

Thankfully, proper archives will have a catalog or “finding aid” to help you know what you’re after. The Rigney Papers, for instance, has an online catalogue that will tell you more or less what is in each box. This is a key guide for finding what you want to examine.

You can also use what previous researchers have cited. When Origins comes out you’ll see, for example, that when I mention the moment Jordan appears to have discovered the name “Two Rivers” for the village in which his story would start, I give the reference “‘Ramblings on the Form of Story’, Rigney Papers, box 24, folder 1, p. 2.” To find what I was looking at, you’d order Manuscript 0197, box 24. Once this was delivered to your workspace, you’d very carefully open the box, very carefully remove folder 1 (you only take out one folder at a time), and very carefully move through its contents (keeping them perfectly in order!) until you found the document entitled “Ramblings on the Form of Story.” Then, very carefully, you’d turn to page 2 and start reading.

Turn pages carefully. Light touches.

As we say in the backcountry, Leave no trace.

When Origins comes out in November you’ll see, I hope, that one of my aims with the book was to share with you—consider this a teaser tasting—much of what’s in the Rigney Papers, with no need to visit! One half of that picture was already provided with The Wheel of Time Companion, which gave us so many of the character and world details that Jordan had so meticulously collected. That was amazing. With this book, you’ll get to see the evidence of the behind-the-scenes process work through which he built all that awesomeness.

So if you’re interested in that story—the twin story of both Jordan and the Wheel of Time—you’ll learn things in Origins, I can assure you.

I certainly did!

–Michael Livingston

The Citadel