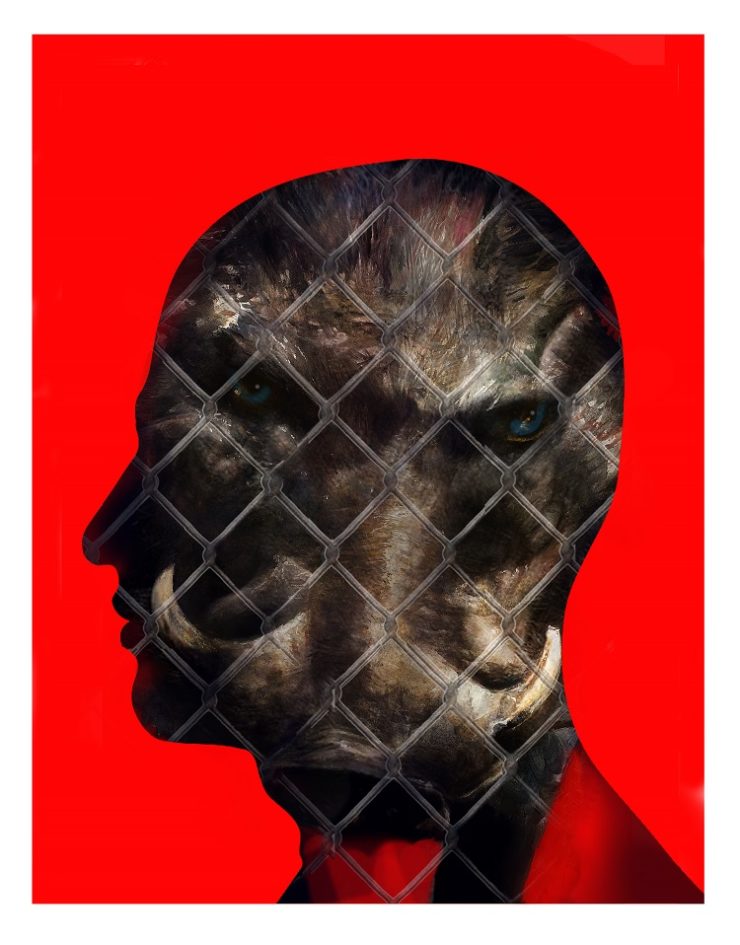

An artist’s work attracts the eye of Andrey Porgee, a notorious gangster, who becomes her best customer.

But when he commissions a painting based on a childhood photograph, the artist fears his reaction to the final product.

Porgee was not supposed to arrive for another half hour but the painter was already afraid. It wasn’t because of the painting. She knew it was one of the best she had done in a long time. She was certain Porgee would like it and most likely buy it. The gangster already owned three of her works and never stopped complimenting her on them. This, however, was part of the problem.

Besides being a very dangerous, frightening man, reputed to have done countless terrible things over the years, the gangster had a big mouth. In one way that was sweet, but in most others it had been the cause of the artist’s recent trouble.

“I tell everyone how fantastic your work is, Ruth. You’re going to have a lot of deep pocket people coming around here saying they heard from me they should see for themselves how great it is. You got my personal seal of approval and that’s saying a lot. Trust me—you’ll see.” Which was true, while at the same time it was a kind of kiss of death for her.

Because the people he told about Ruth Russell’s work were other members of the city’s criminal underworld. Once word was out Andrey Porgee said this woman’s paintings were good, a rush of scary fellows flocked to the gallery where her work was displayed and bought up everything in the place. At first not necessarily because they liked it, but because they were hoping it would get brownie points with the fearsome man.

After a while they even started coming unannounced to her studio to see whatever new work might be available. Often there was nothing new. She had always been a slow worker. Her new clientele didn’t like that. They wanted to be able to say they had just bought a new Russell painting, hoping the news would fall on the right ears.

What Ruth didn’t know was that the first time Andrey Porgee saw her work was an hour after he’d hit a man over the head with a blue Storm Proton bowling ball. Every single person at the bowling alley who witnessed the blow turned immediately away or fled the place. Porgee’s assistant calmly took the ball from him, wiped the blood off it with a clean towel, and put it in the boss’s custom-made ball bag.

Porgee loved bowling and loved paintings. He bowled once a week and went to museums and galleries whenever he could. On a recent business trip to Varna, he made a detour to Vienna only because he wanted to see the Egon Schiele display at the Leopold Museum.

Interestingly for a very rich powerful man, he lived modestly and owned few things, but they were the very best. Things like private jets; yachts or expensive cars didn’t interest him. He drove a two-year-old white VW Golf. At the same time, he wore a rarer than rare George Daniels watch which had once belonged to a bankrupt multibillionaire who carefully took off the watch before killing himself. If one were to visit Porgee’s surprisingly small apartment in the center of town (he lived alone), you’d think the man certainly had good taste, but besides the paintings on display, the place was kind of austere and empty.

“Do you know why I like where I live, Ruth? The wall in the living room. I looked a long time for an apartment with an ideal wall. In this place it’s like my own personal gallery. During the day, just the right amount of light floods in from the windows, and at night I’ve got it lit just perfectly. Your paintings are exactly where they should be,” he said proudly to Ruth Russell one afternoon when they were chatting in her studio.

It was the afternoon Porgee asked if she would ever consider doing a specific commission for him. “I know some artists don’t want to have anything to do with commissions, and I fully understand that. But I like your work so much I just have to ask.”

It was the perfect moment for her to ask him for something. She was wary to even bring it up, but here he was, wanting a favor. Why couldn’t she ask for one in return? It wasn’t even a big thing. Well, maybe it sort of was to her, but to a man like him it should be no problem.

“Before we get into that, Andrey, I have a problem I’d like to talk to you about.”

One of his thin brown eyebrows went up. “Problem? Is it something I did?”

“Well, yes. You and others.”

“Wow, really? Ruth, I’m so sorry. What was it?”

She swallowed, took a deep breath, then just let it all out fast and hard. Because if she didn’t, it would never come out. “Nobody pays full price for my work, Andrey. I mean, nobody who came on your recommendation. They know, but I don’t know how, that you have never paid my asking price. So they say they won’t either.”

In an instant Porgee’s expression shifted down from second gear—slightly concerned—to neutral. Ruth’s eyes widened, frightened she’d crossed a dangerous line. Inside her head her paranoid self yelled, Now you’re fucked! So what if they don’t pay full price? They buy all your work and he started it.

Porgee made a face, sort of between a pout and a grimace. He was not used to being insulted. By anyone. The rare times it happened, whoever made that mistake paid a heavy price. He felt nothing for Ruth Russell the human being, and would have had no hesitation jamming a paintbrush down her throat at that moment. But her creations were important to him and he really wanted her to do this commission. He would think about the insult and maybe do something about it, about her, after the painting was finished. For right now he’d be nice and give the artist a little real-life instruction.

“Do you know what the most valuable mineral in the world is, Ruth?”

She frowned and shook her head. What did this have to do with anything?

“Lithium. More valuable than gold or diamonds. Do you know where the greatest deposits of lithium are? Afghanistan, of all places. Know what the most valuable postage stamp is? The ‘Mauritius Post Office’ stamp. Estimated value around nine million dollars. Then there’s the ‘Treskilling Yellow’ stamp at only three million and so on. Most expensive car ever? A 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO sold at auction for forty-eight million dollars. I could go on. I love bullshit facts like these. I kill whenever I play Trivial Pursuit.”

Just hearing him use that word “kill” put her further on edge. Looking at the scary man, Ruth again shook her head and put out one hand, palm up. As if to say I don’t get where you’re going with this.

He nodded. “But do you know what’s the most valuable thing in the world, Ruth? Much more valuable than any lithium or wealth, religion, or even power? Fear. If someone fears you, I mean really fears you, then you own their world. Every square inch of it. Fear, big fear, is like terminal cancer. Once it gets inside you it spreads and can’t be stopped. There’s no antidote, no antibiotic, no prayer…It wipes you out every time.

“I’ll bet you’ve been afraid of me in all kinds of ways since the moment you found out who I am. True?” Disconcertingly, he smiled broadly. The kind of joyful smile you show after having heard a great story or joke.

“Yes.” She spoke in a very low voice.

“Yes what?”

“Yes I’ve been afraid of you.”

His smile disappeared. “There’s your proof. I’ve never been anything but nice to you, but I still scare the shit out of you just being who I am. That’s why guys like me don’t ever pay full price for things unless we want to. Because people fear us. They know what we can do to them. They’ve heard what we’ve done to others.” He stopped and waited for her to respond.

What she wanted to say but didn’t dare to was “You can afford anything. Why do something so trivial as this?” She tried to keep that off the expression on her face. But Porgee was nothing if not perceptive. He picked up the scent of her silent question.

“You don’t approve, I know. But that’s all right because you see, Ruth, we may occupy the same space but in reality we live in two different worlds. In mine fear is the gold standard. In yours it’s humanity.

“So just so there’s no misunderstanding, I will keep buying your work, because believe me, I am your biggest fan. You can ask whatever you want for it, but I’ll pay whatever I feel like paying. As to the other guys, I guess as long as you sell to them you’ll just have to accept what they want to pay too.

“But enough about that, my favorite artist. Let’s talk about this commission I’d like you to do.”

She hated him then. And she hated herself for not having the mad courage to say to this monster in a bespoke suit, Get out of my place! Get out of my life. I will never sell you another piece of my work. But too often courage is just another hors d’oeuvre for Fear. It pops your courage into its mouth, one or two bites, and swallows.

Unaware of her feelings toward him, Porgee cleared his throat and began.

Although his family was originally from Bulgaria, he grew up in Vienna. His father, Petar, was a games keeper at the famous Lainzer Tiergarten wildlife preserve there. Twenty- four kilometers of pastures and forest, home to hundreds of wild boar, red deer, mouflons, and many other animals.

“I loved that place, Ruth. The only time I was ever really happy as a kid was when I was out there roaming around in the woods with my father. So anyway, my favorite thing was feeding the wild boars. Wildschwein.” Porgee reached into a jacket pocket and carefully pulled out a faded color photograph. He handed it to her. “There were a lot of them in the park. But my favorite was this big guy we named Mickey Mouse. That’s me feeding him in the picture. Huge, huh? He loved bread, especially these rolls called semmeln, which everybody eats in Vienna. We lived next door to a bakery and they gave the day-old stale ones to my father for the animals.

“Mickey Mouse could eat twenty at one go. Really! But we wouldn’t give him that many because he’d get sick. He loved those semmels though, believe me.” Describing all this, Porgee’s voice grew softer, warmer. There was so much gentle affection and joy in it that Ruth was confused. The man speaking now was so different from the one who had all but threatened her minutes before. And what did any of this trip down Porgee’s memory lane have to do with the painting he wanted to commission?

“I want you to paint my photo, Ruth. I cherish that picture. But you can see it’s old and dying, fading away…I love your work, as you know. So I got this amazing idea: I want you to paint exactly what is there, but in Ruth Russell’s signature style. I know how you sometimes use old photographs for inspiration. That painting my friend Frederick Olsen bought…what’s the title?”

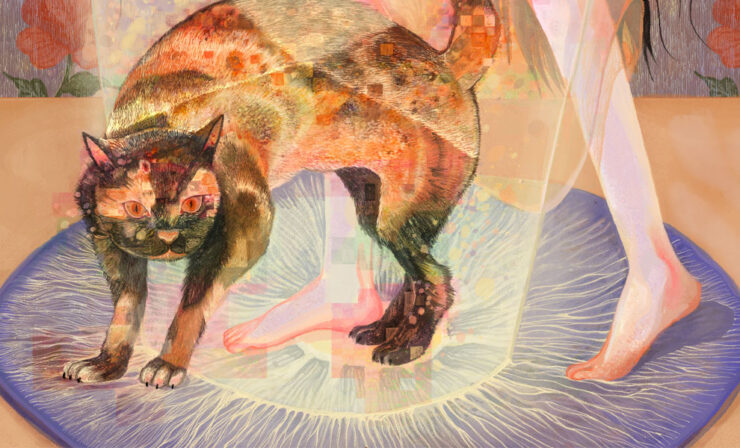

“My title was Kevin’s Kennel.” She’d found the faded Polaroid in a box of old photos at a flea market. A mixed-breed dog cowering inside a small metal kennel. Just outside, taunting the dog with a longish gnarled stick like a magician’s wand, was a squatting shirtless boy with a comically, cartoonishly ugly face. She was drawn to the photo as soon as she saw it. Amusing and horrible at the same time—her kind of image. She loved painting subjects that stirred or rattled a viewer’s emotional response. Diane Arbus meets Looney Tunes. She knew in an instant she had to somehow work this photo into her vision of the world.

Buy the Book

Porgee’s Boar: A Tor.Com Origina

What turned out to be the most interesting part of the process of painting her version of the picture was when she started thinking more and more about the person who took the photograph. What kind of heartless jerk sees a kid taunting a vulnerable dog but instead of telling the kid to cut it out, takes a picture of him doing it? That troubling question scratched more and more on her mind and hand as she painted. Two creeps, years apart in age probably, each in their different ways torturing a poor helpless animal.

The result was her finished work turned out far darker than she’d originally planned. It felt angry heavy and sad, if she could put it that way. An accusation on canvas. Whatever humor she’d seen originally was wiped away the longer she stared at the photo and absorbed the soul of how she perceived it into her work. When she had finished, she made a point of burning the photograph.

Frederick Olsen laughed when he first saw the painting. Told her he used to do that too to all kinds of animals when he was a kid. This dog in the picture even reminded him of one he had back then. Dog’s name was Skippy. Young Freddy tortured it too. Ha Ha. That’s why he liked her picture—because it reminded him of some good old days. He asked if he bought it, was he allowed to rename it Skippy. Ruth looked at the floor a few long moments, then raised her head slowly and said as diplomatically as she could, “I guess if you own it, you can call it anything you want.” She couldn’t make eye contact.

“Excellent! I got the perfect place for it on my bathroom wall. I can look at it every day when I’m sitting on the throne.” He crowed, then paid half her asking price.

“So I’m thinking since you did such a beautiful job on Frederick’s painting, how great it would be if you used the picture of Mickey Mouse and me as your model. A perfect marriage of my history and the artistry of Ruth Russell. I love the idea, Ruth.”

Porgee probably thought he was paying her a big compliment. But all she could think of while looking at his prized photograph was I do not want to do this. No way.

What if he didn’t like the Ruth Russell version of his Mickey Mouse picture? Would she later be found floating in the river, or parts of her, along with the painting? She knew she was being melodramatic but there was definitely some of that fear in her initial reaction.

“What if you don’t like what I paint, Andrey? What if it doesn’t live up to your expectations?”

He smirked. “Not possible.”

“That’s nice of you to say, but really—”

Touching his forehead, he looked irritated for a moment. “I trust your vision and talent, Ruth. Don’t worry about if I won’t like it. If I don’t, I don’t. No harm will come to you,” he said in a booming fake voice like a bad actor. Then gave an amused snort and grew a small smile.

That smile was the wrong one to convince her he was telling the truth.

He made three copies of the original photograph in varying sizes for her, as requested. She insisted they agree on some ground rules before she began work: She could take as long as she needed to complete the painting. He could not for any reason see it while she worked. He bridled at some of the conditions she laid down but in the end agreed. Porgee was not used to negotiating or making concessions. It had been years since that had happened. Originally he told her the size he wanted the painting. She immediately said no. Because she planned to work on three sizes of canvas simultaneously. As she progressed, she would eventually know which one best fit the painting’s subject matter.

He was astonished. “You’re going to make three separate paintings?”

“I’m going to start with three but I’ll know pretty quickly which one to finish. I’ve done this before. The method works. Trust me.”

His smile this time was genuine. He loved the fact she would go to the trouble of trying on three different sizes of canvas before deciding which was best for his picture. He’d never heard of an artist doing that and it impressed him deeply. Maybe if he didn’t like her final product, he really would leave her alone.

She asked him to tell his friends and “associates” to please stop coming to her studio or calling to ask if she had any new work. For the time being, all of her time and energy would be spent on Porgee’s Boar.

A day after she started working on initial sketches, a thin man with tattoos on the backs of both hands in a gorgeous petroleum-blue sharkskin suit delivered a large box to her. He didn’t say a word. Just handed it over and walked away. When she opened the box with some hesitation as to what might be inside, she gasped at what she saw. There was a large array of Old Holland Classic Oil colors, the best of the best oil paints and ridiculously expensive. Along with them were three Kolinsky Sable Series 7 paint brushes. She had heard about these mythical brushes for years but had never seen one. Curious, she later did some research on the internet and came across this description:

“The brush head is made from a Siberian weasel hair known as the Kolinsky Sable. The hair is said to be worth 3 times more than gold.”

At the bottom of the box of these crazy-expensive materials was a handwritten note that said “Only the best ingredients for Porgee’s boar.”

To Ruth’s genuine surprise the work went quickly. By the second week she knew which canvas to use. She put the other two aside. Some days she simply sat and stared at or just thought about the original image. Other days she completely ignored it and only sketched or painted. The more she looked at the original, the more she intuited from it and brought those things over to her work in progress. The process was much the same as when she was painting Kevin’s Kennel. The more she studied the original images, the more absorbed she became in the figures both in and out of the picture. Imagining the unseen photographers became as engrossing to her as their subjects.

With the Porgee picture she assumed the photographer was his father, Petar the gamekeeper. After long sessions of staring at both the picture and into space, her first impressions began to crumble. In time she experienced a series of gradual Eureka! moments. The first came from studying the expression on the boy’s face for what felt like eons, after downing countless cups of tea and coffee, and twice falling asleep in a chair late at night with the picture on her lap.

Originally she saw a little boy looking happily at the camera while the giant nightmarish beast stood a few feet away on the other side of a metal fence, the ground around its feet scattered with all kinds of bread, whole and half loaves, semmeln rolls that looked like sand dollars, and even square slices of white sandwich bread.

“How did I not see that?” She shook her head in wonderment. How could she not have noticed after looking at it for so long? The boy was on the very far side of the photo, almost pushed out of the frame. The picture was dominated by the wild boar. Whoever took it obviously cared more about capturing the best image of the animal rather than of the kid.

When that realization hit her, she looked even closer at the expression on young Andrey’s face. His smile was unnatural, exaggerated, more rictus than real. A smile on demand. A smile to please the photographer rather than one coming from the heart of a little boy. A “please love me” smile.

In the next seconds more truths about the Porgee family somehow came to her directly from what she was sure was the photograph itself. It spoke to her. As had the photo she used as the basis for the Kevin’s Kennel painting, only in that case much less so. She was certain what both photos said to her about their subjects and photographers was true.

Petar Porgee did not like his son at all. There was nothing about being a father that he enjoyed. Ruth closed her eyes and let all of it in a wave of truth wash over her: The father took the boy along with him to the tiergarten sometimes only because his wife ordered him to. She was definitely the Alpha dog in their family. Strong, willful, a wonderful cook, and best of all wild in bed when she was in the mood. If her husband disagreed or said no to almost anything she wanted, she grew cold as frozen stone toward him for days afterward. Which also meant no homemade banitsa or lukanka on the dinner table, no warm, laughing conversation along with a welcome glass or two of rakia waiting for him when he came home from work at the end of a day, and worst of all only her back to him for days when they were in bed.

So now and then Petar took his son with him to the park, but usually only under orders from the boss. Once there, he made Andrey walk too fast and carry the big bag with all the bread in it. If the boy ever stopped and said he was tired or hungry, his father ignored him and kept walking, never looking back to see if he was following. Sometimes Andrey was so tired or hungry that he started to cry but he never stopped following his father. Never once.

Petar never hit him or yelled much, but from an early age Andrey knew full well his father didn’t like him. After his mother died of cancer when he was thirteen, relations between father and son soured even more. By then the boy spent most of his time out of the house, finding various substitutes for family and fulfillment.

His early experience on the streets taught him bad people were more willing to accept him straight away, whereas good people expected him to prove somehow he belonged in their ranks. He also learned he was very good at doing bad things and it was a quick way to gain the admiration of the people he hung around with. When you’re naturally adept at something from an early age, things just fall naturally into place. By the time he was twenty he was a very dangerous, very ambitious man.

Since beginning work on Andrey’s painting, Ruth was not used to getting visitors. She’d told her friends she had an important project and was going off the grid for a while until she had finished it. The gangsters stopped coming to her place as soon as Porgee put the word out to stop. So when her intercom buzzed one afternoon around three, she was surprised.

“Who is it?”

“Frederick Olsen. I need to talk to you.”

For a moment she forgot the name. Then remembered he was the man who bought Kevin’s Kennel.

She was a little uneasy buzzing him in but knew whatever he had to say must be important because Olsen was disobeying what Porgee had told his people—not to bother her.

“I know I’m not supposed to be here, but I won’t take up much of your time—I promise.” He held a large package wrapped in brown paper at his side.

“That’s all right. Come in.”

The last time Ruth saw Frederick Olsen he was tan and healthy looking, like he’d recently returned from a relaxing vacation someplace sunny and festive. Today he looked pasty, unkempt, and noticeably fidgety.

“I don’t want to bother you, but could I get a glass of water? I’m crazy-thirsty these days—I don’t know why.”

She went to the sink, filled a glass, and returned to the front door. Olsen had not moved. Eyes closed, he downed the water in seconds.

“Thank you. Listen, I’m giving you back your painting. You can keep the money. I’m just giving this back to you, no strings attached. Please take it.” He put the package down against the wall next to the door.

Ruth frowned and put a hand against her cheek. “Wow, okay. But why, if you don’t mind my asking.” She looked at the package, then back at the nervous man.

Olsen wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Truth? I don’t like looking at it anymore. I hung it in my bathroom so I saw it all the time. But one day about a month ago I looked and suddenly—bang!—it reminded me of something. Something I did when I was a kid. Not something nice, you know? Something I didn’t ever want to remember. But now there it was—back up out of my memory when I was sitting on the toilet looking at your picture.” The tone of his voice sounded like he was accusing her of something. He glanced down at the package. The expression on his face was clearly fear, like it might be listening to him and not liking what it was hearing.

“After that first time it started happening a lot. It felt like every time I looked at the picture, another one of my shitty memories came up. Like some kind of trigger—I look at the picture and boom, another bad memory came back to me. Like what your stomach does when you get food poisoning.

“I don’t know if it’s because I’m going nuts these days or because of your picture, but I’m not taking any chances. I do not want it around me anymore, okay? Not on my wall, not in front of my eyes, nowhere near me. You keep it. Sell it to someone else. Maybe it’ll fuck them up too.” He gave out a kind of strangled chuckle, handed her back the water glass, and left without another word.

She picked up the package and carried it across the room to where she worked. After unwrapping the canvas, she put it on one of her easels.

It took only seconds for the artist to understand why he didn’t ever want to look at her painting again. At first he’d liked it because he saw himself as the boy in the picture taunting the dog. But like a long-lost key unlocking a room that has been closed for years, Kevin’s Kennel opened the door to all of Frederick Olsen’s memories, an unpredictable and potentially dangerous thing to happen to even a law-abiding citizen, which Olsen clearly wasn’t. His past was probably a hell of a lot darker, more violent and permanently scarred than most people’s.

We want to be able to pick and choose what we remember. But what happens when we cannot? When instead we are swept under by only our many bad memories, the really bad ones, the horribles? The deaths, the rejections, the fatal failures and betrayals, hideous embarrassments, depressions…For some people, particularly bad ones like Olsen, their locked room of memories really should stay locked forever.

The next time Ruth’s intercom buzzed was several weeks later. She had emailed Andrey that his painting was finished and he could look at it whenever he liked. They made a date and he showed up half an hour early. From the time she had emailed him until the moment the intercom buzzed she had looked at the painting nonstop. She walked back and forth in front of it, sat down on the floor and looked up at it. Stood on the other side of the room and squinted at it. Closed one eye then the other to see if her eyes agreed about what they were seeing. They did—it was one of her best works. Frederick Olsen’s visit confirmed what she wanted to believe—both photographs had spoken to her and she understood. She worked what they said into her paintings and that made them…the only word she could think of was transcendent. Magical or touched by the divine maybe, but words and concepts like those made her nervous. So she just assumed for some wonderfully mysterious reason, a part of her painter’s brain had intuitively opened to forces much larger than her imagination and they used what was there in her work.

“Ruth! I’m so excited. Really. So show me.”

She’d set up the easel so it stood in perfect light for that time of day in her studio. There was a shabby blue drop cloth covering the painting. The two of them stood in front of it.

“Andrey, frankly I’m terrified you might not like it.”

He waved a hand in the air as if to brush her fear away like it was a pesky fly. “Just show me.”

She went to the side of the easel and, with an uneasy tug, pulled the cloth off.

After taking his hands out of his pockets, he put both of them on top of his head. He stepped forward until he was only inches away from the painting. Lowering his hands, he put the right one across his mouth. Because he stood in front of her, she could not see the expression on his face. She was encouraged when he dropped his head to his chest. At least he was silent and not blasting her with anger.

“Ruth. My God, it’s brilliant.” He took the hand from his face and moved it back and forth in front of the painting as if trying to feel all of what was there. “It’s so much more than I hoped for. It’s like it’s alive; so vibrant and true.”

“Oh I’m so glad you like it, Andrey.” For the first time she realized she was breathing so shallowly that it was almost like she’d been panting. She could also feel her heart thumping hard and fast in her chest.

“Can I take it with me?”

“Of course, but it will take a while for some of the oils to dry completely so make sure not to bump anything when you go.”

“I can’t get over it. You got it. You caught it. Everything that I wanted is here and more. Thank you. Thank you, Ruth.” He took out his checkbook and, leaning on her desk, wrote a check. He handed it to her, but she did not look at the amount until after he had left. It was five times more than anything he had ever paid for her other work.

To her great surprise and lifelong relief, she never saw Andrey Porgee again after he left. He did call her twice. The first time a week after he came for the painting.

“Ruth, I can’t stop staring at your picture. Every time I pass it I stop and see something new in it. Then I realize I’ve been staring at the damned thing for minutes because there’s so much there to take in. It’s genius. It’s really fucking genius.”

Then a month later a much shorter, far more worrisome call. He sounded drunk or high. His voice was slurred and upset or angry—she couldn’t be sure which. “Ruth? How did you know? Huh? Tell me ’cause I’ve got to know.”

She knew exactly what he was referring to but wasn’t about to answer the question. “Know what, Andrey? I don’t know what you’re talking about.” The other end of the line went dead. That was the last she ever heard from her biggest fan.

Around the same time as that odd last call took place, Frederick Olsen parked his rental car in the Hanover Hill Senior Community parking lot in Buxton, Connecticut. It was a beautiful place and cost a monthly fortune to stay there. He passed the reception desk and went deep into the building until he reached room 154. He knocked on the door. No one answered, so he opened it and stepped in. An old man dressed in cream-colored pants, shirt, and bedroom slippers sat on the side of a tightly made bed, staring out the window.

“Mr. Porgee?”

The old man did not turn from the window, so Olsen stepped closer. “Mr. Porgee, your son Andrey sent me. I brought you rakia. Your son Andrey said you love it. Would you like to drink some now?”

At the sound of the word of his favorite drink, the all but empty Alzheimer’s shell of a man who was once Petar Porgee turned and smiled like a child at this stranger. Olsen took a small glass bottle out of his pocket. It looked like one of the liquor bottles you find in a hotel mini bar or when you order a drink on a plane. There were two paper cups on the bedside table. Olsen took one, poured all of the rakia into it, and handed it to the old man. As he had a hundred times before over a lifetime, Petar tipped the cup back and took it all down in one swallow. The poison was untraceable, and the old man would start to feel woozy in a few minutes and then, lying down on the bed, go to sleep forever. Frederick Olsen took the bottle and the paper cup, patted the old man on the shoulder once, left the room, and disappeared back into the world.

Petar Porgee’s son went on to live many more years doing many horrible things. But ironically he never contacted Ruth Russell again. Because the longer he looked at the painting he commissioned her to do, the more afraid of the painter he became. The more he looked at it, and like Medusa’s head he could not stop looking at it, the more fearful he became of the power and vision of the woman. How could she know these things about him, his life, his pain and his fears? How could she have put them all and so much more into this one painting. She must be some kind of veshtitsa, a witch. He didn’t really believe in that kind of shit, but looking once again at her painting, he could believe anything was possible.

Buy the Book

Porgee’s Boar: A Tor.Com Origina

“Porgee’s Boar” copyright © 2022 by Jonathan Carroll

Art copyright © 2022 J Yang