Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

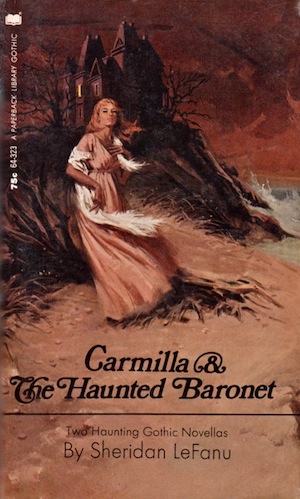

This week, we finish J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 15-16. Spoilers ahead!

“The grave of the Countess Mircalla was opened; and the General and my father recognized each his perfidious and beautiful guest, in the face now disclosed to view.”

Before Laura can leave the Karnstein chapel, a “fantastic old gentleman” enters: tall, narrow-chested and stooping, his face brown and furrowed behind gold spectacles, his grizzled hair hanging to his shoulders. Slow and shambling, he advances, a perpetual smile on his lips and “gesticulating in utter distraction.” Spielsdorf greets him with delight and introduces him to Laura’s father as Baron Vordenburg.

The three men confer over a plan of the chapel, which the Baron spreads atop a tomb. They walk down an aisle, pacing off distances. From the sidewall they strip away ivy to expose a marble tablet—the long-lost monument of Mircalla, Countess Karnstein! The General raises hands to heaven in “mute thanksgiving.” Vordenburg, he declares, has delivered the region from a plague more than a century old, and tomorrow the commissioner will arrive to hold an “Inquisition according to law.”

The trio move out of Laura’s earshot to discuss her case. Then Laura’s father leads her from the chapel. They collect the priest and return to the schloss. Laura’s dismayed to find no tidings of Carmilla. She’s offered no explanation of the day’s events, or why she’s guarded overnight by Madame and two servants, while her father and the priest keep watch from her dressing room. Nor does she understand “certain solemn rites” the priest performs.

Carmilla’s disappearance ends Laura’s nightly sufferings, and several days later she’s let in on her guest’s terrible secret. Her correspondent’s heard, no doubt, about the superstition of vampires. One cannot doubt their existence given the mass of testimony, the innumerable commissions, and the voluminous reports supporting it. Moreover, Laura’s found no better explanation for her own experiences.

The day after the Karnstein expedition, authorities open Mircalla’s grave. Father and Spielsdorf readily identify its occupant as their guest, for long death hasn’t touched her beauty nor generated any “cadaverous smell.” Her eyes are open. Two medical men confirm her faint respiration and heartbeat. Her limbs remain flexible, her flesh elastic. The body lies immersed in seven inches of blood.

Her vampirism proved, the authorities drive a stake through Mircalla’s heart. She utters “a piercing shriek… such as might escape from a living person in the last agony.” Next come decapitation and cremation; her ashes are thrown into the river. No vampire ever plagues the region again.

Laura has summarized her “account of this last shocking scene” from her father’s copy of the Imperial Commission’s report.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Laura’s correspondent may suppose she’s written her story with composure. In fact, only the correspondent’s repeated requests have compelled her to a task that’s “unstrung her nerves for months… and reinduced a shadow of the unspeakable horror” which for years after her deliverance rendered her life dreadful, solitude insupportable.

About that “quaint” Baron Vordenburg. Once possessed of princely estates in Upper Styria, he now lives on a pittance, devoting himself to the study of vampirism. His library contains thousands of pertinent books, as well as digests of all judicial cases. From these he’s devised a system of principles governing vampires, some always, some occasionally. For example, far from the “deadly pallor” of melodrama, they present the appearance of healthy life. Their “amphibious existence” is sustained by daily tomb-slumber and the consumption of living blood. Usually the vampire attacks victims with no more delicacy than a beast, often draining them overnight. At times, however, it’s “fascinated with an engrossing vehemence, resembling the passion of love, by particular persons.” To gain access to them, it will exercise great patience and strategy; accessed gained, it will court artfully and protract its enjoyment like an epicure, seeming to “yearn for something like sympathy and consent.”

Laura’s father asked Baron Vordenburg how he discovered the location of Mircalla’s tomb. Vordenburg admitted he’s descended from the same “Moravian nobleman” who slew the Karnstein vampire. In fact, this ancestral Vordenburg was Mircalla’s favored lover and despaired over her early death. When he suspected she’d been the victim of a vampire, he studied the subject and decided he must save her from the horror of posthumous execution; he believed that an executed vampire was projected into a far more horrible existence. And so he pretended to solve the vampire problem while actually concealing her Karnstein chapel tomb. In old age, he repented this action. He wrote a confession and made detailed notes on where he’d hidden Mircalla. Long afterwards, the notes came to Vordenburg—too late to save many of the Countess’s victims.

After Laura’s ordeal, her father took her on a year-long tour of Italy, but her terror endured. Even now, “the image of Carmilla returns to memory with ambiguous alternations – sometimes the playful, languid, beautiful girl; sometimes the writhing fiend…in the ruined church.”

And, Laura concludes, “often from a reverie I have started, fancying I heard the light step of Carmilla at the drawing room door.”

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: Vampires must sleep in their coffins, within which they float in a pool of blood. (How they shower is never stated, but if they can pass through walls presumably they can also shake off inconvenient stains.) Contra modern guidance, they breathe and blush. The image of “deadly pallor” is mere “melodramatic fiction,” as distinct from whatever kind this is.

Libronomicon: Baron Vordenburg’s library is full of works on the subject of vampirism: Magia Posthuma, Phlegon de Mirabilibus, Augustinus de cura pro Mortuis, and John Christofer Herenberg’s Philosophicae et Christianae Cogitationes de Vampiris.

Anne’s Commentary

As we come to the end of Carmilla, my thoughts go scattershot across the narrative, rather like the black pearls of Countess Karnstein’s court necklace when she was first assailed by her vampire lover, you know, after her first ball? As she confided in Laura? Way back in Chapter VI? I’m making up the part about the black pearls, but what else would Mircalla have worn on such an important occasion?

I’m in the mood to make up stuff about Le Fanu’s masterpiece, filling in its most intriguing gaps. Or let’s call it speculation instead of invention, because I’m not planning to go all wanton here and have that Imperial Inquisition open Mircalla’s tomb only to find a centuries-yellowed note from the Moravian nobleman to the effect that, hah! I’ve tricked all you idiots again! Though that would have been a cool turn of events and just what a bunch of sport-spoiling Imperial Inquisitors deserved.

The biggest knot Lefanu leaves intact in his Chapter XVI denouement is the identity of Mircalla’s lady-facilitator. Clearly the grande dame who so bowls over General Spielsdorf and Laura’s father is not Millarca/Carmilla’s mother. Nor, I think, is she a vampire or other supernatural entity. My guess is that Mircalla has retained enough of the Karnsteins’ wealth to keep a talented actress in her employ, along with various bit players and henchmen as needed. In pursuing the object of its obsession, Baron Vordenburg tells us, a vampire will “exercise inexhaustible patience and stratagem.” It must need both to deal with human helpers. You know what humans are like. In the end, we don’t have to know any more about Mircalla’s servants than we’re told. Once they’ve gotten Millarca/Carmilla into the household of her choice, they will have adequately fretted their hours upon the stage.

Prior to Chapter XV, we meet two medical doctors who know enough about vampires to recognize the symptoms of their predation—and who believe in them strongly enough to risk the scorn of the incredulous. Chapter XV introduces the novella’s real expert, its Van Helsing except that Le Fanu’s Baron Vordenburg precedes Stoker’s chief vampire hunter by twenty-five years. Professor Abraham Van Helsing can append a long string of academic credentials to his name, whereas Vordenburg may have none at all, nor any profession beyond that of nobility down on its luck. Next to the dynamo that is Van Helsing, he’s as shambling as his gait, as lank as his ill-gloved hands, as abstracted as his vague gesticulations, “strange” and “fantastic” and “quaint,” as Laura describes him. Nevertheless, he’s had enough money to preserve an extensive library and enough intellectual drive to master his chosen subject, the “marvelously authenticated tradition of Vampirism.”

Why does Vordenburg study Vampirism rather than, oh, the Lepidoptera of Upper Silesia? Chapter XVI gets really interesting when Laura’s father asks the Baron how he discovered the exact location of Mircalla’s tomb. It turns out that the very Moravian nobleman who relocated Mircalla was himself a Vordenburg, our Baron’s ancestor, whose papers and library our Baron has inherited. Wait, it gets better. The ancestral Vordenberg had a very particular and compelling reason to become a vampire scholar.

As the present Baron fills out the woodman’s tale, his ancestor was in youth Mircalla’s favored lover, passionately devoted to her both during her life and after her death. Presumably driven by grief to get to the bottom of her early demise, he realized she’d been the victim of a vampire and so threw himself into learning all about the monsters. It wasn’t by chance, then, that he came to Karnstein—he must have come there on purpose to slay Mircalla’s slayer, the “index case” bloodsucker. Revenge wasn’t his only goal. He knew that Mircalla might herself become a vampire, or at least fall under suspicion of being one. The thought of her undergoing grisly posthumous execution appalled him. Also he had reason to believe that an executed vampire entered a far worse existence. Such a fate must not be his beloved’s!

So, the Baron relates, he shifted Mircalla’s tomb and let the locals think he’d taken her body away altogether. In doing so, he must have verified that she was indeed undead. What next? Did he hang around for her emergence and a poignant reunion? If he had, and she had loved him as he loved her, wouldn’t she have fixated on him at least as hungrily as she did on Bertha and Laura? Maybe he didn’t stick around to find out, preferring to remember the living Mircalla. Maybe he didn’t want to risk infection himself.

Or maybe Mircalla just hadn’t been all that much into him. Maybe death freed her to express her preference for her own sex? We only know of her, as a vampire, pursuing other women. Of course, we know only a sliver of her posthumous history.

Or her “amphibious” history, as Baron Vordenburg would have it. It’s a term I myself would apply to frogs or salamanders or Deep Ones. What can the Baron mean by it: that Carmilla’s at home both on land and in water? But aren’t vampires unable to cross water, running water at least? Or does he mean she’s at home both above and below ground? Or, more figuratively, that she exists in a state between life and death? I don’t know. The Baron is so quaint.

In conclusion at Carmilla’s conclusion: what I hope is that the “horrible” life my favorite vampire must enter after posthumous execution is no worse than lingering with her light step near Laura’s drawing room door, ghost of a ghost, waiting for a reunion once Laura too changes states.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

At last, we come to the climactic confrontation with the monster who has usurped Laura’s affections, brought her to the brink of death, and cut a swathe of terror and death through the countryside. At last Laura will be forced to admit her beloved’s unworthiness, just as the General achieves his long-sought revenge. Perhaps Carmilla will be shocked, at the last, that the object of her obsession prefers to consummate their love with her death—or perhaps she will try to persuade Laura to die sweetly into her despite it all. Perhaps Laura even hesitates, torn by the knowledge that they cannot both survive. One can only imagine the dramatic confrontation, fraught with peril and emotion…

Because the actual scene is reported to Laura second-hand, sanitized of any hesitations or fears on the part of the men who kill Carmilla, and takes place while the undead fiend sleeps. In lieu of melodrama, we get one last infodump.

I have issues with Poe, but I feel like he could’ve handled this more dramatically. Or better yet, Mary Shelley. Hazel Heald. Someone who doesn’t like to tie things up neatly and scientifically offscreen.

(My favorite part of the infodump is the repeated description of vampires as “amphibious.” Land and sea, life and death, are indeed both impressive boundaries to cross on a regular basis.)

Maybe Le Fanu is running headlong into his choice of narrator, and simply can’t imagine her protectors permitting a young girl to witness the staking directly, let alone participate. Maybe her father and the General are worried about exactly the ambivalent reaction described above. But still, the General has been blunt enough about his earlier experiences that it seems strange to have his reactions left out of this story. Laura’s father, too, doesn’t seem to have shared any of the relief and gratitude one might expect.

In fact, it’s not clear which why we’re reduced to the inquisitor’s report at all, without any added commentary by the other men there. Perhaps the matter-of-fact description is all Laura’s willing to pass on. Maybe we’re getting that ambivalence after all, in this distanced bare-bones voice.

Or maybe someone’s lying. Again. After all, it can’t really be the case both that most vampiric victims turn into vampires, and that the area around the schloss becomes vampire-free as soon as Carmilla is gone. Laura’s father could be sheltering her on that Italian tour from the continued danger of Carmilla’s baby vamps, even as the General and Baron work cleanup. Sheltering her, too, from any more dramatic details of their final confrontation.

Or maybe the liar is closer to home. Maybe Laura—like the Baron’s ancestor—is reporting her beloved’s death in order to keep her beloved alive. Thus the minimal detail. Thus the contradictions.

Thus Laura’s untimely death, shortly after sending out this almost-confession?

Vampires, Laura tells us, yearn for sympathy and consent from their victims. Nor are they the only ones who’ll fool themselves in pursuit of that deadly affection. Laura, too, yearns—and even on the page, stays in denial about Carmilla’s nature far beyond the point of sense. Perhaps it’s not merely a fancy that Laura hears, even as she writes, the vampire’s step at her drawing room door.

Next week, “Gordon B. White is Creating Haunting Weird Horror” in a Patreon that we don’t actually suggest subscribing to. In two weeks we start on our next longread: N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became!

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out July 26th. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.