Welcome to Close Reads! In this series, Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, author Liz Harmer looks back at a particularly unsettling episode of The X-Files, and muses on religious trauma.

The X-Files feels formative to me, in the same’ way Star Trek: the Next Generation does, in the way that TV still could in those pre-streaming days. Shows just came on—you didn’t choose them; they were bestowed upon you. But even though The X-Files was often unfurling in the background of my neighbourhood and in my own house, “Die Hand Die Verletzt,” a standalone episode from season 2, is the only episode I can remember with any specificity.

(Content Warning for mentions of rape and spiritual abuse.)

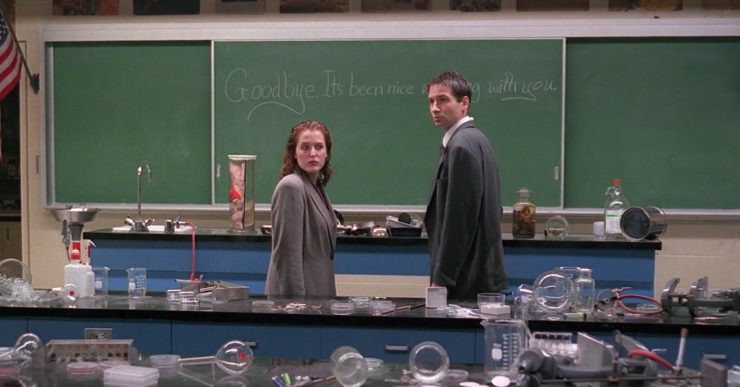

No UFOs, no connection to the smoking man, “Die Hand Die Verletzt” focuses on a one-off event: a demon visits a New England town to punish a lukewarm cult of Satan-worshipping teachers for their lapse of faith. There is no room for alternative explanations as there are in the demonic shows I’ve lately been subjecting myself to, such as Evil or Archive81, where perhaps what we have is hallucinations or trickery, perhaps what we have is mere sociopathy using the devil as a scapegoat. No, in “Die Hand Die Verletzt,” both the believer (Mulder) and the skeptic (Scully) see the same events. Frogs fall from the sky, water drains counter-clockwise, a snake kills, eats, and digests a man in an impossible amount of time: something supernatural and evil is really happening.

The episode means to parody the religious hypocrisy of Christians by showing the lack of true belief among the Satanic teachers. It opens on a discussion of the inappropriateness of Jesus Christ Superstar, the twist being that these teachers are galled not because they are socially conservative but because of their demonic religion. The parallels to American Christianity come up again in one of the cult’s leader’s explanation of his religion’s origins, dating back generations in New England: “They fled persecution from people being persecuted, all in the name of religion.”

Scully reminds us that the Satanic Panic, even by the mid-nineties, has been discredited as a mass hysteria: “The FBI,” she says, “recently concluded a 7-year-study and found little or no evidence of the existence of occult conspiracy.” And in a line that would have haunted me at 14, Mulder tells one of the Satanists that “even the Devil can quote scripture to fit his needs.”

When I watched this episode on a small-screened, bulky-backed TV, probably in the summer of 1996 or 1997, I was a young teenager keyed up about the possibility of occult conspiracy. We were in my grandparents’ mobile vacation home in the Adirondack mountains. Night fell and all light outdoors was swallowed, so that the light of the trailer felt to me a floodlight, a target, a bulb that might attract things the way moths were attracted to any source of light. There was a region of this trailer, a hallway between two bedrooms, that I was too petrified to cross at night and would be even as a grown woman.

Those were days when many things could keep me from sleeping, or could keep me from going into the basement or the upper floor alone at home: from around age nine until a mental health crisis at seventeen, I was often afraid. I was a religious child in a religious community, too, a child who had to turn off the radio if Marilyn Manson came on, a child who would never be able to watch The Exorcist, and a child who was sure that the world was filled with demons.

On this particular night, my brother and I were to be sleeping on the floor of the living room. The episode seared into me in flashes: chants, candles, blood, screams, the Devil and her full-pupiled eyes. After my parents and grandparents went to bed, and the lights were out, I lay in my sleeping bag on threadbare carpeting, clutching my hands and praying desperately, perhaps as sweating and intense as the demon-in-substitute teacher Mrs. Paddock when she was sweatily setting curses on everyone. I prayed for Jesus to surround me with angels. Jesus, I prayed, you promised that you would not leave me open to evil if I asked you. Protect me, protect me, protect me, I prayed, imagining that angels were surrounding my bedding and that I would be safe if—and only if—I stayed inside the region delimited by the sleeping bag.

One way to shock yourself about how much a person can change in a lifetime—especially one who has gone through a very long period deconversion—is to watch something that once moved you to a desperate state of fearful muttering and discover it now leaves you cold. Nervous that I would be upset again by “Die Hand Die Verletzt,” I watched it for the second time in my life in 2022 in a well-lit café in Southern California in the middle of the afternoon. A few moments felt tense—especially the opening, in which some boys verbalize an incantation and TV-demon noises (that kind of rustling, mocking feeling of many voices whispering at once) begin to sound—but mostly the episode doesn’t feel like anything to me, now. It doesn’t trigger the feelings I had then. This is what it’s like to lose your faith completely. It’s not replaced. It’s just gone.

I was, in my youth, developing an elaborate belief system about how the devil and his minions worked as I applied my over-active intelligence and my over-active imagination to the scraps of largely contradictory theology I was carefully picking up. One thing I believed, for example, was that Satan could get intel on you if you prayed out loud, so it was better to pray silently, which only God could hear. There were doors everywhere and membranes, there was a dangerous porousness in a person. Be careful what you hear, little ears, went a Sunday school standard. Be careful what you hear—but how?

Technically all this was superstition and therefore, to us, heretical. I remember asking why I should be afraid of reading the horoscopes (which I gravely was) when God said nothing could separate me from his love. Better not to tamper, I was told, better not to meddle, better not to stir up whatever was down there—you don’t need some spirit to notice that you are looking at it. You don’t need to invite something evil and powerful in. So it deeply frightened me when, in the episode, certain utterances seem to invoke a demon, and when another character runs away repeating a Catholic prayer.

But part of me wonders if what frightened me most about this episode was a part that I had entirely forgotten until my rewatch. It’s absolutely the part that frightens me most now. In a long scene, a traumatized teen—who, later in the episode, is demonically compelled to slit her wrists—confesses to Mulder and Scully that she has been ritualistically raped, watched her babies be murdered, and seen her sister killed. It all comes to her as a sudden rushing in of a repressed memory, and she cries and talks as saliva pulls in trails between her lips.

The idea that I might have experienced something horrific and not remembered it—the fact that I am a person who is traumatized—disturbs me even now. Though we were not evangelicals in my tradition, we were conservative believers. I absorbed many beliefs from outside our smaller faith community, so the claims that many former evangelicals have made that there is something traumatizing about this belief system resonates with me, even though we weren’t evangelicals and I am loath to water down the concept of “trauma.” These “ex-vangelicals” as some of them call themselves, have pointed out that the definition of C-PTSD might fit a child who lived in terror of the idea of hell, or was exposed constantly to apocalyptic imagery, or was treated to a special kind of religious misogyny, or who believed there were beings all around who wished them the worst of all possible ill. And none of this leaves you when you leave the church.

Because it distresses me, now, to see how quickly the traumatized teen and her plotline was dispensed with. To see that no one gets any care for her. She is left with “friends” and later tries to finish her biology final. The adults can’t help her; no one can. The adults had no choice but to serve God/Satan/whoever happened to be their Lord, and this meant, sometimes, sacrificing their child. Maybe it should not be a surprise that I felt unsafe and afraid when I was small, and that I didn’t trust that the few and paltry hexes I did have could save me.

Buy the Book

Strange Loops

Liz Harmer is the author of The Amateurs (2018) and Strange Loops, which comes out in January.