Whether you’ve got a replica, a doppelgänger, or a straight-up clone, having a duplicate of some sort certainly helps you move through life a little bit easier, from a temporary stand-in to a more permanent kind of donor. But they have to know how to successfully emulate their source material, right? Which means that you probably have to train them up. Here are a few of those times that training your duplicate (knowingly or unintentionally, closely or indirectly) came in handy…

Battlestar Galactica’s Cylons

When your entire society is made up of only 12 models, the average Cylon is bound to run into dozens of others with their face, if not their identical personality. The Number Six and Number Eight models in particular find that they range from sweet to savage, empathetic to humanity’s struggle or fervently worshipping the Cylon cause. To manage these disparate personas, each number’s class includes senior figures who help shape “younger” models, from the rebirth nurses who assist the resurrected Caprica-Six to “overseer” Sixes who orchestrate the human/Cylon breeding between Sharon/Athena and Helo Agathon.

Speaking of the Number Eights—if they didn’t look alike, Athena and Boomer could be entirely different people. Their run-ins have tended more toward body-swapping than mutual help; however, when Athena arrives on a rebel basestar later in the series, she encounters a group of Eights who beg her to lead a mutiny against the cruel Sixes. Instead of letting them blindly follow her, she delivers her one and only crucial lesson: to choose a side for themselves.

Star Trek’s Data and Lal

Data is a sort of duplicate of his own creator, Noonian Soong, who based all of his androids on his own physical person. But Data was able to develop on his own, separate from his human parents, being discovered apparently “abandoned” at the Omicron Theta colony by Starfleet. Becoming an officer of Starfleet and valued member of the Enterprise crew, Data eventually makes the choice to create his own “child”, as it were, in the form of Lal. She’s not an exact replica—in fact, she’s quite a bit more advanced than Data is in a number of way, and develops the ability to feel emotions before him—but she is trained according to Data’s personal desire to be more human. When Lal is about to be separated from Data by Vice Admiral Haftel, the emotional burden proves to be too much for Lal, and she suffers from neural net cascade failure. It’s possible that if Data had created Lal to be a bit more similar to him, she might have more easily survived.

Molly Southbourne and the mollys

From her first lost tooth, Molly Southbourne learned to always fear when she bled. Fear, and then react—as each drop of blood created a duplicate molly (which she intentionally thinks of in the lowercase), Molly trains so that she can be ready to murder her doppelgängers at a moment’s notice no matter the situation, from scraping her knee to losing her virginity. An unnamed prisoner hears this grisly origin story in Tade Thompson’s The Murders of Molly Southbourne, as a grim Molly recounts her many kills and her discoveries about just how deadly the mollys—and Molly herself—are. But she’s not just talking to hear herself speak; by the end of the novella, the prisoner comes to realize that she too is a molly, except she’s the first molly who hasn’t wanted to murder her predecessor on sight… and Molly doesn’t know why. The best way Molly can sum up her training is to cite a fictional epigraph from one Theophilus Roshodan:

With each failure, each insult, each wound to the psyche, we are created anew. This new self is who we must battle each day or face extinction of the spirit.

Whether it’s nature or nurture, something about the circumstances of her imprisonment has shaped this twelfth molly into something entirely different…

The Doctor and the Meta-Crisis Doctor

The Doctor’s duplicate—a human-Time Lord hybrid created during the Tenth’s Doctor near-regeneration experience at the hands… plunger… of a Dalek—is imbued with the Doctor’s memories and desires, and a dangerous anger that comes from being born in battle. The Doctor knows his duplicate can become a better man, but not on his own—instead, he leaves the Meta-Crisis Doctor on an alternate Earth with Rose Tyler. Rose is hesitant, but the two Doctors are so in snyc that the duplicate immediately understands what the Tenth Doctor is hoping he’ll do—tell the woman they both adore that he has a human life to share with her, along with those three little words she’s been desperate to hear, given freely. The Meta-Crisis Doctor gets the chance to have what no Doctor has ever experienced before: a life on the slower path with someone he loves.

Carers in Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro’s quiet novel Never Let Me Go (which was adapted into a film in 2010) is all the more disturbing for how placidly it lays out its premise: Kathy, Tommy, and Ruth—three friends in a love triangle, who came of age at boarding school together—discover that their sole purpose is to provide organ donations to the people who cloned them. They never actually meet their “possibles,” aside from one point where Ruth thinks she’s tracked down her older predecessor; this only enhances their existential crisis, if they can’t even confront the reason behind their short lifespans. The “training” herein takes on two parts: boarding school adolescence, in which the clones are encouraged to paint and discouraged from smoking, keeping their bodies and souls “pure”; and caring. That’s the name for a potential career path for clones like Kathy, who look after their fellow clones who have donated once, twice, three times, and are nearing “completion” of their life’s purpose. Ishiguro’s writing matches this feeling of inevitability… that is, until the clones hear the rumor that they can defer their donations, if they can prove they’re in love.

Lincoln and Tom in The Island

Released the same year that Never Let Me Go was published, Michael Bay’s surprisingly nuanced thriller also tackles the ethical dilemma of clones-as-organ-harvesters; but in this case, the truth is kept from them. Instead, Lincoln Six Echo and Jordan Two Delta believe that they are part of humanity’s last surviving enclave, protected from the supposedly inhospitable world inside a compound where all they do is eat well, work out, indulge their artistic sides, and hope that they win the lottery for “The Island”—a paradise free from contagion. It’s an idyllic existence—until they discover that “going to The Island” is a euphemism for donating essential organs to your sponsors, whether they’re comatose or alcoholics, or even serving as a surrogate mother for a sponsor who can’t conceive. While Lincoln has spent his short lifespan being primed to be the perfect specimen, the real training is when he comes face-to-face with his brash, hard-partying, Scottish sponsor Tom—and then has to learn enough about him to fool the assassin after them in a classic “no, he’s the clone!” shootout scenario.

Sam Bell in Moon

In Duncan Jones’ Moon, the protagonist doesn’t create his own clone, but he does have to work with him to foil a dastardly plan. Sam Bell thinks he’s coming to the end of a three-year lunar assignment, eagerly anticipating heading back to Earth to reunite with his wife and baby daughter. When he’s in a frightening accident during a routine EVA, he’s grateful to wake up back in the base. But—how did he make it back? He investigates the accident site, only to find himself, barely clinging to life. This is kind of a shitty way to learn that you’re a clone. The two Sams quickly realize that they’re only the latest in a long line of Sams, and, even worse, that they’ve only been designed to live for three years. Which means Older Sam only has a few days left to teach Younger Sam everything he’s learned, figure out a way to send Younger Sam back to Earth, evade the prying eyes of their bosses, and work out a plan to expose the horrific truth of the lunar colony, to ensure that no Sam Bell has to go through this again.

MEM by Bethany C. Morrow

MEM takes place in an alternate 1920s Montreal, where a process of memory extraction can remove traumatic memories from people and processed into “mems” living people, who breath and eat, but have no true sentience. These duplicates are not “trained” so much as “locked away and forgotten”—the whole point of them is to free their “sources” from the weight of the past, as they relive and react to the memories they were born from. But then we meet “Dolores Extract #1” who seems to have a consciousness of her own, and a will, not to mention a passion for movies. (In fact, she’s rejected her given title and taken a new name, Elsie, from a favorite film character.) Rather than accepting any training from humans, Elsie is determined to educate herself, and find a way to live a life apart from her creators.

Bobby Wheelock (The Boys From Brazil) and Algernop Krieger (Archer)

In The Boys From Brazil, iconic ’70s thriller writer Ira Levin used historical fact to create a terrifyingly loony conspiracy theory. Nazi hunter Yakov Liebermann receives a phone call regarding a series of mysterious murders in Brazil, and soon learns that former SS operatives have been activated to kill 94 men—all of them 65-year-old civil servants, each with a 13-year-old son. The reason? Well, the men’s sons are all clones of Adolph Hitler, and Mengele is hoping that one of the boys will recreate history. Luckily one of the cloned boys, Bobby Wheelock, rejects Mengele and sets the family attack dogs on him.

The book serves as a reference point for a long-running subplot in the ’60s spy parody series, Archer. Dr. Krieger, the mad scientist responsible for both cybernetic advancements and pig hybrids (and the sole authority of Fort Kickass) spends two seasons insisting that he’s not a Hitler clone—“If I was a clone of Adolf goddamn Hitler, wouldn’t I look like Adolf goddamn Hitler?”—carefully not mentioning that he was raised in Brazil by a Nazi scientist, and only came to the U.S. after his pack of Dobermans ate the man who might have been his father. But in Season 5 the gang visits a Central American dictator and discovers the man has three Krieger clones, who are all working together to launch a nerve gas attack on New York, and have clearly been trained in a level of organized evil that our Krieger never achieved. Original Krieger fights them, three Kriegers are killed, and the one that’s left insists he’s Original Krieger.

But isn’t that exactly what a clone would want you to think?

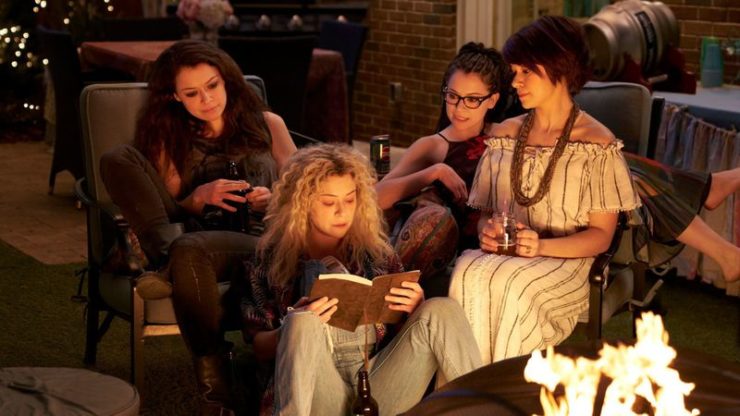

Orphan Black’s Clone Club

Two words for you: CLONE. SWAP. Adaptability must be a strong gene among Project Leda, because Sarah and her sestras have a remarkable penchant for getting mistaken for one another and then having to lean into that. The clones aren’t so much trained as baptized by fire, like in the pilot when Sarah has to fool Beth’s boyfriend mere hours after learning her doppelgänger exists (it says a lot about both of them that she succeeds); Cosima as Alison, in which she accidentally “outs” herself as queer to the PTA; anytime Helena barely manages to play a cartoonish, and usually murderous, version of one of her sestras; and our personal favorite, Sarah-as-Rachel interrogating Alison-as-Sarah. Except in rare cases where they have enough warning to prep one another, the clones usually just have to wing it, based on whatever mannerisms and quirks they’ve picked up simply by spending time together. It’s the best sort of training in that it’s more organic, and speaks volumes about the depth of their various relationships.

Originally published July 2019