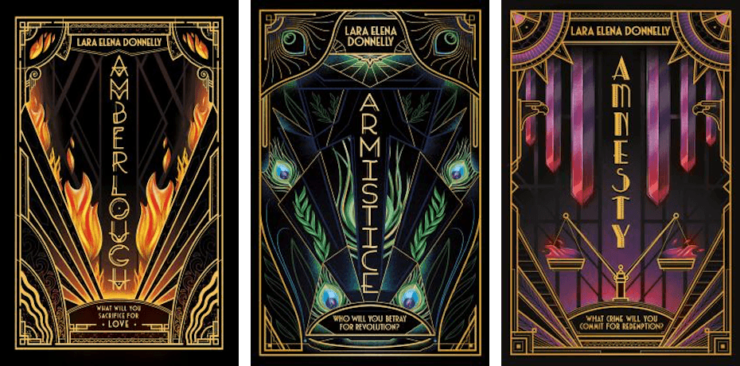

This month, I’d like to call attention to a trilogy from a few years ago called the Amberlough Dossier by Lara Elena Donnelly (whose new book Base Notes just came out, though I haven’t had a chance to read it yet). It’s a spy story in the vein of Le Carré set against a decadent backdrop inspired by Cabaret.

The main characters in the first book are Cyril DePaul, a scion of an important family who works as a spy for the government, and Aristide Makricosta, a cabaret singer and emcee who also happens to be a crime boss. Cyril is supposed to be investigating Ari and breaking up his crime network, but they become lovers instead. The third main character in the first book is Cordelia Lehane. She’s a dancer in the same cabaret as Ari, and when politics comes for her friends, she gets revenge.

The setting is a country called Gedda, which is actually a confederation of four republics. At the opening of the series, the One State Party is running a candidate in the presidential election, and they are willing to do anything to succeed, including cheat. The OSP, who are referred to as the Ospies by most people outside the party, wants to replace the federation with a single government for Gedda and to expel all the foreigners. So they’re basically fascists, and Amberlough City is 1936 Berlin.

I was impressed with a lot of things about this series, but the one most relevant to this column is Donnelly’s linguistic worldbuilding. The republics within Gedda can be loosely mapped onto real-world locations by way of their languages. Donnelly didn’t invent languages for this trilogy, instead using character and place names to create this sense of strange-but-familiar places and people. The republic of Nuesklund has Dutch-sounding names; Amberlough has Anglo names; Farbourgh in the north has Gaelic-ish names and its residents speak with a burr. The neighboring country of Tziëta has Slavic-sounding names. This type of worldbuilding is subtle, perhaps enough that a lot of readers will completely overlook it, but it makes the world feel more real.

Buy the Book

Amberlough

In the real world, language exhibits wide variation from place to place and across time. If you’ve ever taken the “which U.S. dialect do you speak?” quizzes online, you should be somewhat familiar with this idea. And if you’ve ever been on the internet and been utterly confused by some term the youths are using, you know that slang changes with every generation. (I still unironically call things “rad.”) Adding this kind of variation into your fictional setting and dialogue creates such depth.

The slang Donnelly’s characters use has a very jazz-era feel to it. I didn’t find these terms in my search for historical slang terms, so they apparently aren’t from the real Jazz Age in the U.S. The internet is imperfect, though, and the slang could come from a real, historical source that simply didn’t show up online. Here’s some examples: “straight” for a cigarette from a pack (as opposed to hand-rolled), “tar” for opium, being “pinned” about something meaning to be angry about it, and “sparking” for having sexual or romantic tension. There’s even a variant slang used by a character from the north. Instead of “sparking,” he says “frizzing.” He also uses the word “ken” meaning know, which is a real-world word currently used mainly in Scotland. Donnelly also draws on real-world 1920s and ’30s slang as well, words like “swell,” both as an adjective meaning good (“oh that’s swell!”) and as a way to refer to a rich person (“see that swell over there?”).

Another of the real-world aspects Donnelly incorporates seamlessly is linguistic prejudice. We may or may not want to admit it, but we judge people based on their accent and dialect. (See Anne Charity Hudley’s website for some current research in this field.) Language use is intimately linked with identity, and people are aware on a conscious level of many of the associations we make between language and identity. If you hear someone with an accent like comedian Trae Crowder’s, your mind automatically calls up a whole lot of associations, and his comedy career is based on upending the audience’s assumptions, proving himself to be the opposite, in many ways, of the associations attached to his accent.

Cordelia, the cabaret singer and dancer, comes from a slum called Kipler’s Mew with a very distinctive dialect, which she worked to get rid of so she could get out of the structural poverty she was born into. Her accent, when she allows it to come out, is described as a “nasal whine,” particularly on the /i/ sound. I imagine it as being kind of like Eliza Doolittle from My Fair Lady or Fran Drescher in The Nanny. I don’t know if that was the intention, but that’s how I imagine it. When she relaxes into her native dialect, she uses ain’t, drops her g’s, and uses a variety of colorful expressions. I really like “you can turn that around,” which is equivalent to “the pot calling the kettle black” or “I know you are, but what am I?”

Aristide also employs an accent to shape the way people perceive him and to create an identity. He’s not from Amberlough City originally (and revealing where he came from is kind of a spoiler, so I’ll leave it at that.) When he gets there and works his way up to being an entertainer, he affects the accent used by the well-to-do locals. Cyril comments that he likes the affected stutter which is part of the posh Amberlough accent, and remarks on its absence when Aristide doesn’t use it.

There’s so much thought and detail to appreciate here, but to sum it all up, the linguistic worldbuilding in the Amberlough Dossier is wonderful, and stands as a great example of how a writer can subtly work these elements into their prose and add depth, making the world and characters feel genuinely real. Have you read the trilogy? What did you think? Let me know in the comments…

CD Covington has masters degrees in German and Linguistics, likes science fiction and roller derby, and misses having a cat. She is a graduate of Viable Paradise 17 and has published short stories in anthologies, most recently the story “Debridement” in Survivor, edited by Mary Anne Mohanraj and J.J. Pionke. You can find her current project, a book on practical linguistics for writers, on Patreon.