Ruthven Todd (June 14, 1914–October 11, 1978) was better known for his poetry, scholarly work on William Blake studies, and (as R. T. Campbell) mysteries. He also wrote children’s books, some of which were science fiction. In particular, he wrote the Space Cat series.

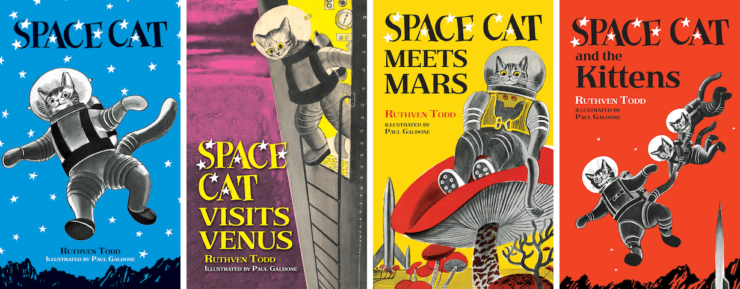

Flyball is a cat. Who—and this is the complicated part—lives in space. His career is documented in four illustrated volumes: Space Cat (1952), Space Cat Visits Venus (1955), Space Cat Meets Mars (1957), Space Cat and the Kittens (1958). All four are illustrated by Paul Galdone (June 2, 1907–November 7, 1986).

I have not read these since 1969. How did they stand up? I am glad you asked.

Space Cat (1952)

Old enough to wander unsupervised, Flyball the kitten sets out to explore the world. The opportunistic cat exploits human inattention to hitch a ride in a taxi, and then on an airplane, before being discovered by Captain Fred Stone. Fred names and adopts the stray kitten and takes Flyball to a military base out in the desert.

Whatever security measures are in place at the base do not extend to cats. Flyball soon has the run of the place, which he uses to supervise the humans. Intrigued by Captain Fred’s plane, the kitten stows away. When Fred is assigned to take a new rocket for a test flight, Flyball stows away on that as well.

Convinced the cat is lucky (as opposed to, say, needing more supervision than it is getting), Fred insists that the cat accompany him on humanity’s very first trip to the Moon. Fred’s superiors acquiesce because they would not dream of taking away a man’s good-luck charm. When Fred leaves for the Moon on rocket ship ZQX-1, Flyball accompanies him.

It’s good that he does, because the Moon is both more wonderful than expected—there is life—and more dangerous. Fred’s life will depend on the ingenuity of one small cat.

Readers may wonder what Flyball’s family made of his absence the day he wandered out, never to return. For his part, Flyball is quite pragmatic; he saw his siblings as competition for food. Once adopted by Fred, he never thinks of his family again. The cat has a surprisingly rich interior life for an animal with a brain the size of a large plum, but very little of it is wasted on entities he will never meet again.

Galdone consistently portrays Flyball walking around on his hind legs in the manner of a human. The text does not support this. Later books limit the cat to more feline stances.

One might expect that at some point, after Flyball has crept into a taxi, two different planes, and an experimental rocket ship, the humans would start looking down at their feet and checking for a pesky cat. Nobody ever does, a hint at their general state of alertness that makes me wonder what else they’ve missed as they construct their space rockets.

Todd does not provide a lot of information about the lunar biosphere, perhaps because it did not matter to the plot, or perhaps because these are very short novels—novellas, really, and I might be being generous at that—and there simply was no room. Not when there’s a dying spaceman with a cracked helmet to rescue.

***

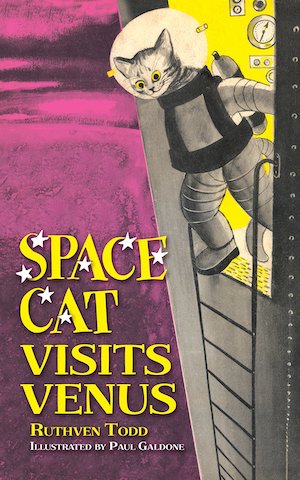

Space Cat Visits Venus (1955)

Now a mature tom a year or two old, Flyball is the top cat—the only cat—in America’s lunar city. Constructed almost as soon as the US reached the Moon, the lunar facility is a means to an end. The fuel requirements for a return mission to and from the surface of Venus would be impossible for a chemical rocket launched from the Earth. A rocket launched from the Moon has enough payload for a human…and his cat. Or as Flyball prefers to think of it, a cat and his human.

Hoping that Venus will be habitable but aware that the odds do not favour it, Fred is surprised when Halley’s dials indicate a breathable atmosphere at reasonable temperatures. Venus’ plant life is odd-looking and more mobile than its Terrestrial analog, but all in all, Venus seems to be a potential second home for humans. Curiously, there is no sign of animal life.

As they explore the region near Halley, the two explorers realize they are being herded. Venus’ natives have had unpleasant experiences with off-world invaders in the past, and they make very sure the human and the cat are harmless before revealing themselves. Not that two Terrestrials would have spotted the local intelligent beings without a bit of help. Venus is home to a vast network of intelligent commensal plants.

Bridging the gap between Terrestrial animal and Venusian plant might have proved impossible, save for the providential fact that Venus plants are not just telepathic, but some of them can induce telepathy in other beings. Touch the right plant, and Fred and Flyball can telepathically speak to it.

Human and cat can also speak to each other directly for first time in their relationship, which raises the potentially troublesome question of what they will make of each other now that they do not have to guess what the other is thinking.

The focus in these books is on Flyball, but his human acquits himself fairly well. Venus is a darn peculiar world but Fred takes it all in stride. Whether it is the idea of a world run by cooperative plants, or the fact that he’s having a conversation with his cat, nothing throws him. It helps that many developments that in other hands would be the things of horror (like a world full of small-c communist plants capable of reading minds and who knows what else, or the revelation that interplanetary invasion by seed is a thing that happens sometimes) are, in Todd’s hands, simply more diverting wonders of a rich Solar System.

In stark contrast to the lax safety procedures in the first volume, Fred’s first reaction when the Halley’s equipment tells him that the air outside is breathable is to assume that the equipment is broken. He performs independent tests to make sure the results of removing his helmet will not be tragic. At no point does he think “Well, I carried the cat here for a reason” before exposing Flyball to Venusian air. This puts him well ahead of a number of space explorers I could mention…

***

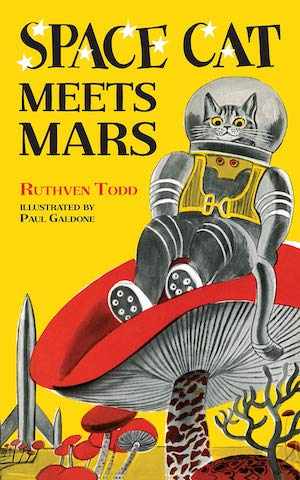

Space Cat Meets Mars (1957)

A near miss from a massive asteroid drags Halley off-course. Fred’s failure to check Halley’s rocket tubes for obstructions before leaving Venus compounds the situation. Halley was supposed to return to the Moon. Instead, the space craft ends up near Mars. Providentially, it has sufficient fuel reserves to set down on the surface of Mars where Fred can carry out repairs.

While Fred is busy repairing Halley, Flyball is free to explore Mars on his own. Mars is less alien than Venus but still pretty odd. The insects are unnecessarily large and not frightened of Flyball in the least. There are mice but they turn out to be entirely metallic, not the delectable morsel a hard-working space cat deserves.

There is one bright note: Mars has cats! Or rather, Mars has cat! Moofa is the last of the Martian fishing cats. After her family was lost in a sandstorm, Moofa never expected to see another cat, let alone an experienced spacefarer like Flyball. She can show Flyball the wonders of Mars, while he can offer her the universe.

This is not a kissing book. It was so close to being the space feline version of A Rose for Ecclesiastes. Ah, well.

Losing her whole family was clearly traumatic for Moofa (as it was not for Flyball). She spent quite some time looking for them before giving the search up as futile. In its understated way, Space Cat Meets Mars is a rather melancholy little work.

You may have questions about how there are cats on Mars. These will not be answered.

***

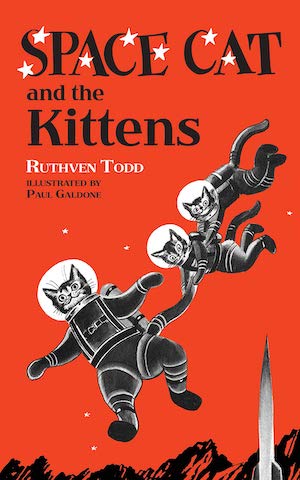

Space Cat and the Kittens (1958)

OK, maybe Space Cat Meets Mars was a little bit of a kissing book.

Flyball, Moofa, and their kittens are joined by their human Fred and fellow crewman Bill as the cats set out on a grand new adventure. Cats and their humans are no longer satisfied with exploring other planets in the Solar System. Einstein is no mere rocket ship. It is a hyperdrive-equipped starship: Next stop, Alpha Centauri!

Habitable worlds seem to be a dime a dozen in this universe. Alpha Centauri has at least one, a planet somewhat smaller than Earth. Like Mars and Venus, it has native life. Where Venus was the world of plants, and Mars dominated by bugs, this world has miniature versions of extinct animals from Earth—everything from long-lost megafauna to dinosaurs. Carnivorous dinosaurs.

The Alpha Centauri mission carries far more cargo than the old interplanetary rockets. Accordingly, the expedition surrounds its base with an electric fence. This will keep out the small but voracious carnosaurs that would like nothing better than to eat the visitors.

The expedition also brought a helicopter. It’s small but effective. Thanks to an unfortunate orientation of its rotors, it provides two foolish kittens with a bridge over the electrified fence to the predator-filled world beyond.

Humanity seems to have gotten from chemical rocket ships to starships surprisingly quickly. How much time has passed between Space Cat Meets Mars and Space Cat and the Kittens is unclear. How humanity fares on Mars and Venus is also unclear. What is apparent is Fred’s concern for the native life of Alpha Centauri’s world, which he fears may not do well once humans arrive in numbers.

Like a number of series, the Space Cat books are subject to diminishing returns, each book a bit less interesting than the one before. Presumably the kittens were intended to be to Flyball what Robin was to Batman. They are instead what Cousin Oliver was to The Brady Bunch. This installment is, I fear, mainly for completists.

***

I had not expected to see a Space Cat book again. We live in a golden age of reprints. These are aimed at younger readers (or the very nostalgic). If you don’t mind the fairly hefty price charged for the reprint and you have a small SF fan (or if you read these fifty or sixty years ago and are curious how they stand up), you might consider giving them a try.

Originally published in September 2020.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.