I grew up terrified.

When I was 12, I wasn’t particularly afraid of clowns or monsters or troubled ghosts, but as puberty hit at the start of middle school, I was terrified of myself.

I was a gay boy in the early 90s and though I didn’t quite have the vocabulary for it, I knew that I wasn’t like any of the other kids at my all-boys prep school, where masculinity was modeled, crafted, and policed in very specific ways; ways I feared I did not—and could not—match. I knew the game “smear the queer,” and played it as the smearer and the smeared with a knot in my stomach, because it taught me the inevitable violence attached to being different in that way. Smearer or smeared, those were the only options. Though no one ever said so explicitly, every message I received told me that if I was gay, I was doomed.

This was 1992 and I only knew the word “gay” from the evening news and locker room taunts. It was a curse. Gay meant laughable. Gay meant perverted. Gay meant AIDS and sickly death. Something was wrong with gays, said the politicians. Gays deserved what they got, said the flocks of the faithful. And if I was gay, then I’d deserve whatever I got too. That thought filled my prayers with pleas to change me and my nightmares with visions of all the horrors that would befall me when I couldn’t change. I tried not to think about holding hands with the other boys, or wrestling with them and losing, or any of the millions of fleeting thoughts that an almost 13 year old is helpless against. The more I fought, the more I failed, and the more I failed, the more afraid I became.

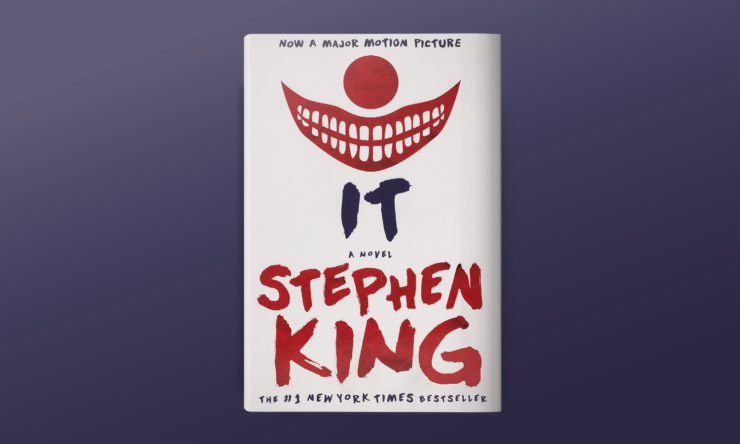

And then, that 6th grade year, I read Stephen King’s IT, and it made my horrors vivid, grotesque, and real.

And IT saved me.

It’s not a perfect book (what book is?) and it is very, very long, and it is not without problems (what book isn’t?) but it was precisely the book I needed then, horrors and hatreds and all.

IT tells the story of the Loser’s Club—Bill, Richie, Beverly, Mike, Eddie, Ben, and Stan—as they encounter and battle a recurrent evil living beneath the quaint town of Derry, Maine, first as children in 1957, and then as adults in the 80s. They battle bullies and neighbors and even parents who are infected by that evil, which comes to back every 27 years to torture the young with their worst fears and then to feed.

As anyone who saw the 1990 made for TV adaptation, or the recent Hollywood duology, or the SNL parody knows, the monster at the heart of IT appears most often as sewer-dwelling clown, Pennywise, but the clown is merely a manifestation of fear itself. Like the best of Stephen King, the real horror is in the mind. Though the descriptions of dismemberments and deaths are gruesome, IT delves into the adolescent mind and its terrors better than most.

I guess I thought if it was a book about 11 year olds, it was easily a book for me at almost 13. Like I said, I wasn’t afraid of clowns.

Within a few pages, I saw all my fears come to life.

An early section of the novel describes a gay bashing and the violent murder of Adrian Mellon, a gay man, with all the homophobic language my 13-year-old vocabulary contained. It even taught me a few brand new slurs against myself. Whether I feared being beaten and thrown over a bridge before reading the book or whether it birthed that specific fear in me, I can’t say, but I read that section breathless, because there it was, in black and white on the page of this 1200-page book: that the adults around me said and thought the things I feared they said and thought. I wasn’t crazy. My fears were valid, or else why would a horror writer write them? I felt seen. Scared, but seen.

Middle-schoolers aren’t taken very seriously by our culture. Their tastes are mocked; their emotions blamed almost entirely on hormones, and their fears are often ignored. And yet Stephen King, one of the best-selling authors in the world, took my fears seriously. He believed in them enough to use them as a source of horror and to show them in all their grisly detail. It wasn’t a comfort, exactly, to be taken seriously, to be shown my own nightmares back to me, but it was a help. On the inside, I was screaming and this writer from Maine, he heard me. I was no longer screaming alone. As he writes toward the end of the novel, as the Loser’s Club tries desperately to defeat their tormentor before their energy and power evaporates, “…you know, what can be done when you’re eleven can often never be done again.” King takes young people seriously.

There was more to the representation of hate crime in IT for me, though. The opening section is, undoubtedly, filled with problematic stereotypes and hateful language, but when the bullies and the cops toss their anti-gay slurs around, they are not celebrated for it. The author is very clearly judging them. The gay-bashing is the first evidence the reader gets that evil is returning to the town of Derry; that something terribly unnatural is afoot, and it’s not homosexuality. The hate is unnatural, the hate is evil. When we get into the head of Don Hagarty, Adrian’s boyfriend, and the author lets the reader know him in his own thoughts—the first time I’d ever known a gay person outside of the news—he’s sympathetic. He’s smart and loving. He also sees the town for what it is, sees its evil clearly and wants to leave it.

Though the characters in the book don’t empathize with him having seen his boyfriend brutally beaten and murdered, the author does. He shows the gay character from his own point of view as fully human. And he had a boyfriend! That was a thing a person could do! A boy could have a boyfriend! I never, never, ever imagined that was possible before then. I’d never been exposed to such an idea before.

I couldn’t believe it. Stephen King thought gay people should be able to date and hold hands and live their lives. Stephen King did not think gay people should be tortured or killed. He thought that those who would torture or kill gay people were in the service of evil, as were those who would tolerate it or look away. The victims of homophobia did not deserve to be victims. Homophobia, Stephen King seemed to say, is not the natural way of the world. It is a monstrous thing and those who practice it are a part of the monster. He made that a literal fact with a literal monster.

This was revolutionary to me. In my pain and fear, I learned to imagine that I did not deserve pain and fear. I was not the monster and even if that couldn’t protect me from the monsters in our world, that was the monsters’ fault, not mine.

Would I have liked to see gay people as more than victims? Sure, in hindsight, this narrative played right into the idea that to be gay was to be a victim and it would be a while before I was able to imagine myself as both gay and heroic, or to see that reflected in a story, and I was still terrified of what this world did to gay boys, but I no longer felt alone. I’d been shown who the monsters were, and that was the beginning of defeating them.

But IT didn’t just make flesh out of my darkest fears. It also made flesh out of my queerest desires.

Yeah, I’m talking about that scene. Near the end. In the sewers. With the group sex.

No, it was not “appropriate” for a not-quite 13-year-old, but then again, neither was the evening news. Both confused the hell out of me.

I read it again recently to make sure I actually remembered this thing, and there it was, several pages of pre-teen sewer sex, and I can see why it makes many readers uncomfortable. It made me uncomfortable. It’s a strange scene, fetishizing adolescent female sexuality through the only fully realized female protagonist. But at almost thirteen, I didn’t read it that critically. I read it gaspingly, graspingly, the way a drowning victim reaches for a life preserver. I read it to save my life.

Be warned, there are spoilers ahead.

Buy the Book

City of Thieves

In IT, while fighting the monster below Derry, who turns out to be a giant pregnant female spider alien—the mind-bending gender nuances of that choice were lost on me at the time—the Losers Club gets lost in the sewers, and they begin to lose themselves. Bev, the one girl in the group, has the idea to strip naked in the dark, then and there in the underworld, and make love to each of her best friends one at a time. She loses her virginity and experiences her first (and second, and third…) orgasm.

No, I didn’t fully understand what I was reading, or what an orgasm was or that Bev was having multiple ones, or why the boys taking turns losing their virginity with Bev should help them find their way out of the sewers again, but it did help me find mine.

I didn’t know much about sex, though I did know that I had no interest in the kind of sex that society held up as right and good and moral. By performing a radical act of consensual, profound, non-monogamous, loving sex with her friends, Bev showed me that sexual liberation was possible. That there were other ways to express sexuality and they were not necessarily wrong or dirty. Before this scene, Bev battled deep sexual shame, yet as she is having all sorts of mystical coital revelations, she thinks, “all that matters is love and desire.” She is freed of shame.

My brain nearly exploded.

I wanted love. I had desire. Like Bev, I battled shame. Yet Bev’s love for her friends took an act she had thought was dirty, and made it beautiful and made it life-saving, literally. I mean, the scene happened in the sewers, where the town’s dirt and filth flowed, and yet it was presented as an essential moment in our heroes’ journey. What others might see as disgusting, was life-giving. Only after the group sex, are they able to escape.

Until then, when I thought about sex at all, I thought about death. I truly believed the desires I had were death. Sex was death.

But in IT, sex became life. The scene gave me my first ability to imagine a different relationship to my desires. Maybe to someone else, they were dirty as a sewer…but to me, maybe they could be life-saving. Sex was dangerous. Sex was weird. Sex was not death.

And yeah, imagining myself as Bev, and the boys of the Losers Club as my friends who I very much wanted to get closer to was a safe way to explore that desire without revealing my secret or crossing any lines or doing anything unsafe, physically or emotionally. I got to live through Bev and the boys in that magical double consciousness that literature provides. I got to experiment with adulthood, in all its contradictions, and with sexual liberation and queer sex in all its awkwardness, without ever taking any risk whatsoever. I was safely ensconced in a pillow fort I’d made under a drawing table in my playroom, while the Loser’s Club deflowered each other in the sewers under Derry, Maine.

And that was the magic of IT. It was a dangerous book, a book I was far too young to read, and in its danger, I found safety. The book told me what I knew: that the world was not safe for boys like me, but it also told me that it was okay to be afraid, that I was not the bad guy, and that joy was possible. My joy didn’t have to look the way anyone else thought was right or appropriate or wholesome. Love could be complicated—it was for the Losers Club—but love could look all sorts of ways and love, scary as it is, will defeat monsters in the end.

I still went through middle school terrified. The monsters were very real and I remained very afraid of them, but I’d looked horror in its silver eyes, with Stephen King as my guide, and I hadn’t blinked. I’d find my own way through the sewers and my own Loser’s Club, and I’d live to write my own stories one day.

I had Stephen King on my side, and armor as thick as IT. I was ready to fight.

Originally published October 2019.

Alex London is the author of over 25 books for children, teens, and adults, with over 2 million copies sold. For middle grade readers, he’s the author of the Dog Tags, Tides of War, Wild Ones, and Accidental Adventures series, as well as two titles in the 39 Clues series. For young adults, he’s the author of the cyberpunk duology Proxy and the epic fantasy Black Wings Beating. He’s been a journalist reporting from conflict zones and refugee camps, a young adult librarian with New York Public Library, an assistant to a Hollywood film agent, and a snorkel salesman. He lives with his family in Philadelphia, PA.