For the residents of this mycological ecosystem, creating art feeds the World around you and requires working in harmony with your inner voice. When one artist’s voice begins screaming, he’s forced to travel farther than he ever has before to reconcile with the noise in his head and find his true place in society before it’s too late.

In the darkness, the voice in his head is screaming again.

Kenji crushes his knuckles into his temples, even though that’s not where the pain—or the voice—really is. But the agony is unrelenting, unspecified; it’s coursing through his body, making his muscles clench and his molars grind. And the screaming, oh God, the screaming. The voice in his head is screaming loud enough to drown out the raging metal band on the front, center stage. Painful enough that Kenji squeezes his eyes closed, shutting out the audience around him—all those glowing people, jumping to the time of the music, like a stuttering heartbeat.

Then there’s a moment, just a second, when the voice pauses in its shrieking and Kenji opens his eyes, only to find Eva standing next to him looking concerned. The bioluminescent mushrooms she picked on the way to the concert decorate her hair, giving her an unWorldly look. She can’t hear the screaming voice in his head, but she can read the expression on his face.

She knows something is wrong.

“Air,” he mouths, and points toward the door. Eva begins to shoulder her way out, pushing against the illuminated bodies of the audience, but he waves her back, shouting: “I’ll be okay.”

The voice in his head starts screaming again.

Stumbling toward the exit, pushing against the crowd of glowing people, it’s a struggle to keep putting one foot in front of the other when his muscles seize and his head’s ringing with strings of incoherent syllables, and none of this should be happening. But Kenji keeps pushing on. Pushing through.

By the time he’s outside the venue, the episode is almost over. His muscles are relaxing, breathing becomes easier, and the voice in his head sounds hoarse. It’s already mumbling “Sorrysorrysorrysorry.”

Kenji sags against the building, sweating, gulping down lungfuls of air, warm and muggy, like a half-drowned man. He feels some of the polypores growing on the building break and rupture under his weight. This is not the first time his voice has pulled a stunt like this, and if this is like those other times, he’ll feel normal again in a few minutes.

In a few minutes, it will be like nothing happened at all.

Which makes Kenji want to vomit. It’s the lie, the doubt, the false sense of security that scares him most, because if there’s something wrong with his voice . . . If it’s . . .

People in this World can’t survive without the voices in their heads.

In the darkness outside the concert venue, he feels the music throbbing through the boards of the road. It’s now background noise to the sound of the Endless River rushing by a hundred paces away. Which is to say, everything seems abnormally quiet now that the screaming has stopped.

Kenji’s relieved to be alone, to have this moment to himself before returning to the concert and living the lie—the one that says everything is fine. The towering fungi trees growing randomly on the road shush gently in the breeze. There’s no one else around.

Except for a girl, clearly a student, on the prowl. She has that stance that looks like wanting, like minor desperation. She’s glowing only slightly. He notices her too late.

By comparison, Kenji’s own skin radiates like a damn beacon. I need to take care of that tonight, he thinks. His glow is almost indecent. The girl spots him easily and smiles like a hunter striking lucky, quickly weaving her way around the fungi trees, vanishing the space between them in a breath.

“Sorry to bother you,” she says, though her tone apologizes for nothing. “Do you mind? It’s for school. What do you think?” She thrusts a button into Kenji’s hands, and he’s tempted to make an excuse or tell her off. The last thing he wants to do right now is talk about art.

“Doesn’t everyone want to discuss art?” the voice in his head whispers conspiratorially, even though he’s the only one who can hear it. “Isn’t it what you live for?”

Yes.

Or least that’s what everyone says.

Kenji stares at the button, fights to keep his hands steady. The button is a common brown mushroom cap, treated and painted aqua and lavender, with an elegant luminous script that says Given/Give Back. It’s pleasing and well executed, on its own. But Kenji has seen it before. Too many times.

“Good work,” he says. “Clean lines and nice color contrast. Maybe ease up on the background details, though. It detracts from the text.”

It’s a weak critique, uninspired. But Kenji doesn’t feel particularly moved by art tonight. There are a thousand other buttons like it in the World. A thousand other artists with the same message.

The girl nods seriously, diplomatically. She peppers him with other questions, asking about composition and the overall effect of the message. But Kenji gives her terse answers and her friendly demeanor shifts into wariness.

“Thanks for the feedback, mister,” the girl says quickly. Too quickly. She’s already backing away.

“Good luck with the assignment,” Kenji says, though he knows what she’s thinking.

A reluctance to talk about art is a sign your voice is dying.

As soon as she’s out of sight, Kenji empties the contents of his stomach at the base of the nearest tree.

Softly, his voice mumbles, “It’s okay. It’s okay,” as he wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. It sounds remorseful. And Kenji so badly wants it to be true.

He exhales, tilts his face upward, like in prayer. The flesh of the World looms overhead; the living, breathing ceiling of flesh dotted with every mushroom in existence. Keeping his gaze fixed upward, Kenji touches the base of his neck.

“You all right, babe?”

He turns to find Eva standing behind him. Outside, away from the crowd, he can see her clearly, the patchwork of acid-burn scars that blankets the left side of her face, muting her frown some, but not enough to hide her worry. “What’s wrong?” she asks again.

Kenji feels his voice’s mantra of “It’s okay” on his lips. He bites it back.

“Sorry, didn’t mean to drag you away from the show,” he says.

Eva shrugs, an easy rolling gesture that shows off her broad, beautiful shoulders. “Music’s catchy but still derivative of the genre that inspired it. What’s going on?”

His voice whispers: “Everything’s okay. Promise.”

And it feels true. The pain and screaming that were so visceral moments ago are echoes now. But this is the third episode his voice has had in three days and the worst one so far.

“Kenji, tell me,” she says.

They say your voice screams when it starts to die. And when your voice dies, so do you.

One way or another.

Kenji takes her hands, his own trembling. “We need to talk,” he says.

Kenji was never an artist, though he tried. He tried and tried. But his best efforts in poetry, drawing, music were never more than mediocre, if the critic was being generous.

When asked what the hell he was doing reading ancient how-to books, he said he studied history for inspiration. When asked what this unWorldly mess was supposed to be, he said he tinkered with new tools to improve his art.

This was a lie he told to everyone, but mostly to himself.

Then, three years ago, Kenji invented the thinnest, palest paper anyone had ever seen. Well, not so much invented it as rediscovered it. He found an old manual in the First Givers’ records on papermaking,

It took experimentation. Many, many, many hours of it. He had to figure out the deckles and moulds, the slurry, the couching. The manual called for tree pulp, and the eucalyptus trees in the records were nothing like the fungi trees Kenji knew. The most difficult part was finding the right mushroom for the slurry. So many of those early attempts crumbled in his hands.

White turkey tail mushrooms gave different results.

He called his invention an art project. But when Eva held that first sheaf, still wet and dripping in her hands, she said: “This isn’t art. It’s so much better than that.”

“What’s better than art?” his voice asked, and Kenji agreed, repeating the words out loud.

He regrets that now. How he doubted her in that moment as she held his creation and imagined.

It took her hours of experimentation and countless failed attempts. Their parents, friends, and mentors couldn’t understand how the sheaves of paper on their living room floor were supposed to be art. They whispered to Eva, when they thought he couldn’t hear, that perhaps Kenji was hampering her artistry.

But after Eva made her first paper sculpture, no one questioned Eva’s creative vision or Kenji’s tinkering again.

Kenji remembers holding that sculpture, marveling. It was an ecru-colored replica of a turkey tail mushroom, a material transformed, reborn. It was the first of its kind in the World.

Why don’t we learn more about our history? he wondered, silently thanking the ancient manual he’d found.

“No good can come of it. Stop asking questions,” his voice hissed. It was something his parents would say.

But as Kenji held up the sculpture in his hands, for the first time, he wondered why his voice was lying.

There’s a hole in every home, just large enough for an adult to lie spread-eagle. In a spare bedroom or where a tub should be or in the wall of a closet. A cutaway revealing the soft, sticky flesh of the World, always meticulously scrubbed of fungal growths.

In Eva and Kenji’s tiny apartment, the World is in the farthest corner of their living room.

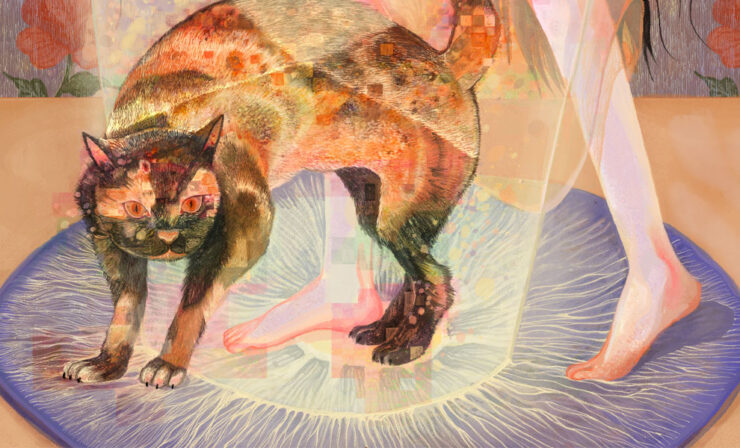

Kenji’s standing naked in front of the cutaway, the World’s exposed tissue, dark and gray, spread out before him. His skin glows brightly, unabashedly, all those nutrients shining through his pores. He doesn’t want it, doesn’t want to glow. The curtain that usually sequesters the World from their living room is crumpled in his hands.

He understands it’s a symbiotic relationship. To live in the belly of the World is to be given and to give back. The World feeds them, a boundless variety of mushrooms and waterlife from the Endless River. In return, they feed the World. Though why the World will only accept nutrients when the voice in your head is alive and well is one of the great mysteries in life. Maybe it’ll be the subject of his next research project.

That is, if the World accepts him tonight.

With his heart hammering a staccato beat, Kenji pulls shut the curtain behind him. Eva catches his hand.

“Wait. I want to watch. Please.”

The bioluminescent mushrooms she wore to the concert earlier that evening still decorate her hair. Her expression is one she usually reserves for her harshest critics—she’s expecting him to argue.

Kenji nods, lets go of the curtain. Usually giving back to the World is a private affair, but tonight, he’d rather not fight. If this is the moment when his voice finally fails him, he doesn’t want to be alone.

He touches the World with a toe first. Its flesh is warm and damp. It always sinks a bit under his weight, like an invitation. Slowly, he nestles the heel of one foot into the living tissue. Then the other. Leaning back, he spreads both arms. Maybe it won’t be so bad this time, he thinks.

He always thinks that.

He settles his head down, letting the nape of his neck touch the World.

At contact, the voice in his head ruptures into giggles, joyfully, brazenly, as if it was waiting for this moment. It’s the only time Kenji ever hears it laugh.

Giving back to the World is like being held too closely, too greedily. Like having your best intentions siphoned out of you, calorie by calorie. Like drowning as you’re being sucked dry. All while the voice in your head giggles, whispers unconvincing platitudes.

It feels like an eternity, but the whole process takes twenty, maybe twenty-five minutes. And when Kenji emerges, slick with sweat and the spit of the World, his skin barely glows at all.

He hears Eva sigh in relief as she drags a blanket over him and helps him to their bedroom. He catches tears in her eyes.

Kenji listens to her bare feet slapping against the floor as she moves back to the hole in the living room and steps in. He waits. He listens to the long sheets of his homemade paper rustling by the open window and the Endless River beyond that. Smells the stink of the sap glue Eva’s using for her latest sculptures, sitting in their unassembled piles on the bedroom floor. For once, Kenji relishes the scent. It wouldn’t be home without it. Exhausted as he is, he stays awake, waiting for Eva and for the World to finish with her.

His voice is mercifully silent.

Eventually, he feels her curl in bed behind him.

“Nightmare of my week,” she mumbles. Her breath’s warm on his shoulder as they lie skin to skin. She takes nothing, but if he could, he’d give her everything.

“If my voice is dying, I probably have one, maybe two weeks left,” Kenji whispers. He pulls her arm around him, suddenly desperate to be held by her. “What are we going to do?” It’s the question they’ve asked each other ten, eleven times tonight. Lobbing it back and forth like a ball.

Eva touches the spot on the back of his neck. The small raised mound of flesh. The place where the voice in your head really lives.

He rubs his thumb over the familiar mountain range of scars on her left hand. “What can we do, Eva?”

In the darkness, the dimness of their now dull bodies, Kenji can barely see her hand in his. But he hears the stubborn, hardened determination in her voice when she taps that spot on the back of his neck and says, “Cut it out. And get you a new one.”

Five years ago, Kenji met Eva on a boat on the Endless River. Or she met him. She was glowing brightly and the scars on her face were still fresh and red when she surfaced unexpectedly from the water, near his raft, swam over, and said: “Mind if I join you for a minute?”

“Um, sure,” he said, surprised that anyone was swimming in the middle of the River, where not even fishing boats bothered to go. There was nothing of artistic or nutritional interest here. Which was why Kenji liked it.

Eva hoisted herself onto the raft, a mostly smooth motion, though she winced slightly as she took the weight off her left arm. The hand poking out from the dripping sleeves of her wetsuit was red and crumbled with burns, too. He scooted over to make room for the dripping, mysterious woman.

“Thanks,” she said, squeezing river water from her hair.

“You’re a long way from shore,” Kenji said. “Are you trying to swim across?” He’d heard of some people training to do this, for sport. Kenji never understood the appeal. The River’s water was icy and boats were simpler, easier.

“No,” she said. “I was trying to swim down.” His voice hissed, and Kenji’s eyes widened in surprise. But before he could say her life was valuable, Eva held up a hand and said: “Not like that. I want to hear the World’s heartbeat. Somebody said you can hear it in the middle of the River.”

“Why?” he asked. It was a weird, fascinating idea, to try to hear more of the World. He sort of wished he’d thought of it himself.

“Why not?” She studied him for a moment. “How do you know the World is living? We see such a small part of it.”

“That’s ridiculous,” his voice whispered, “of course it’s alive.” But Kenji gritted his teeth, focusing on this bright, strange woman. There was a dangerous edge to her questions about the World, like holding black paint too close to a pale, perfect painting, and from the cautious look on her face, she knew it, too.

His parents always said Kenji was too curious for his own well-being.

“What if it’s an animated corpse?” he asked.

Her expression relaxed. “Maybe it’s a giant death cap.”

“Or someone’s twisted art project.”

“Oh shit, can you imagine? What a sick asshole.” They giggled while the voice in his head tsked its disapproval.

“And?” Kenji asked, leaning forward.

“And what?”

“Did you hear it?”

Eva grinned. “I heard a long, slow thrumming. And if that’s the World’s heartbeat, it’s nothing like ours.”

“Of course. The World is beyond your understanding,” his voice said. But Kenji didn’t care about the World right then.

“Hey, I’ll row you back to shore. Which pier do you want me to go to?” he asked, picking up the oars.

Her smile died. “Any one. They’re all the same,” she said in a stiff, flat voice

Kenji knew he’d misstepped, then. He wished he could swallow back the words and return to the moment when they were laughing carelessly about the World.

But he didn’t know how.

So, he rowed to the Enoki Pier, the one he was going toward anyway. They traveled in silence for a while until they were only a few minutes from shore.

“Aren’t you going to ask?” she said finally.

He guessed that she was talking about her face and arm. The burns, the waxy new skin. “Sure,” he said. “What’s it like being a mermaid?”

Eva raised an eyebrow. “What’s a mermaid?”

“Folklore from the First Givers. Beautiful, deadly creatures that live in the water and are half man, half fish.”

“Sounds uninspired. You read those old stories?” she said. “Why?”

Kenji gave her a half smile. “Why not?”

Eva smiled then, and it was brighter than her glow. That was when Kenji knew that he had finally found someone as dangerously curious as he was.

“What do you think’s at the end of the River?” she asked.

“Maybe there’s another colony.”

“Yeah. Full of terrible rowers.”

They laughed, though Kenji’s voice was tsking again. For once, though, it was easy to ignore the pestering voice in his head telling him to stop asking absurd questions. He was too focused on the beautiful person in front of him, trying to commit her to memory, convinced this would be the last time he ever saw her. That she’d slip away like so many of his artistic dreams.

“Let’s meet again,” she said when they landed at the dock.

Kenji’s heart swelled.

Buy the Book

Questions Asked in the Belly of the World

A new voice. It’s beyond anything Kenji ever imagined. It’s like looking up the Endless River, into the bottomless dark beyond civilization, and picturing yourself traveling into it. The thought made Kenji nauseated.

“What if my voice is just sick and not really dying?” Kenji asks. He shepherds the breakfast on his plate from one side to the other. He doesn’t take a bite.

His voice is quiet this morning; it only speaks in sleepy tones. His skin is dim, the neighborhood is still asleep, and the previous night at the concert feels like an ugly dream.

“You said yourself it’s only a matter of time,” Eva counters. There are dark circles under her eyes. They both slept badly, and their debate has taken on sharp, desperate tones. “Why aren’t you eating?”

“Not hungry. Besides, can’t shine if I don’t eat.” Fewer nutrients means he has less to give back. Kenji knows it’s not a sustainable solution, but it’s more plausible than replacing the voice in your head.

“Maybe you can take my voice,” Eva says, as if suggesting he take her jacket or shoes.

“What? No! This isn’t some weird art experiment, Eva.”

“Isn’t everything art?” she replied, sounding weirdly like his old mentors. “Screw food.” Eva shoves her breakfast away, stands, turns in their apartment like it’s suddenly become a cage. “I can’t look at these walls anymore. Let’s go for a walk.”

It’s a joke between them that they can solve any problem so long as the soles of their shoes hold out.

Kenji follows her silently, too tired and angry and frightened to debate the impossibility of a new voice.

They follow their feet, which lead them downstream, through civilization, such as it stands. Hundreds of buildings, tall and narrow, line both sides of the Endless River, curving up gently to follow the contours of the World. Dozens of little alleys are veined between buildings, where bands experiment and compose in their narrow paths. Murals of mushrooms and glowing people cover every blank space, blending and bleeding together. Even in this sleepy, early morning hour, there are poets and dancers on each corner, showing off their creations, desperate to be heard. There are students, too, palms full of buttons, scrambling for feedback. Some people glow, some don’t, but no one shines too brazenly.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” his voice whispers.

It is, but Kenji also sees a World stalled out on art. And he wonders why.

He and Eva cross into the historic district. The skeletons of the First Givers ships rise above the skinny buildings, their metal frames housing museums and markets. The ships are symbols, ghosts devoured down to their bones, repurposed for other projects. For some reason, the sight of these dismantled ships always makes Kenji’s heart ache.

Why do we consume everything? he thinks.

“Given. Give back,” his voice whispers.

Kenji swallows hard, focuses on keeping pace with Eva’s long stride.

In the shadow of one of the ships, in the middle of the road, amid the steady din of art—the colors, prose, melodies, eager to be noticed—there is one entry that commands attention.

Eva’s masterpiece towers.

It’s a beast of a sculpture, unpainted, contrasting with the bright, attention-grabbing colors of everything else around it. It’s a perfect paper replica of a First Givers’ ship. Ghostly pale, imagined whole. There is a chorus of paper people gathered around the base, and on the top of the paper ship, there’s a ladder rising up. And on the uppermost rung there’s a child, arm outstretched, paper fingers almost brushing the ceiling of the World. Almost touching the place every artist has prayed to, but has never reached.

“Wonder what crazy sculptor made this beauty,” Kenji whispers, and elbows Eva, forgetting their ongoing argument.

“It’s what happens when your partner invents the thinnest, creamiest paper in the World.” Eva wrinkles her nose. “God, my gluing technique was a mess back then.”

“A disaster. What will the public think?” Eva shoves his shoulder, and Kenji grins. Pride swells under his breastbone as he stands at the base of the sculpture, even after all these years. It took him fourteen months to make all that paper for her. Then she took his simple invention and turned it into something extraordinary.

It’s been a while since they last stood here together, shoulder to shoulder. It feels nice.

Then he remembers why they don’t come often.

The historic district is now awake enough that someone’s recognized the paper genius with her beloved sculpture. Suddenly, one person comes up to them, then two, then five. All wanting to talk to Eva about her projects and her techniques, or wanting feedback.

Kenji can tell from the stiffness in her posture, her slight lean back, that the last thing she wants to do right now is talk about art. But she’s polite, chatting for a minute or two before Kenji makes excuses about unfinished obligations at home and steers them forward. It’s a practiced routine. But they only manage to walk a block or so until they’re stopped again.

Then Kenji has the most desperate excuse of all. Without warning, his voice begins to scream again.

He fumbles an apology to Eva and her adoring fans and ducks into an alley between two shops. Fear flashes across Eva’s face as she moves to block him from view. He’s shaking, heart pounding, trying hard to look normal, trying not to make a scene.

“Food poisoning,” he hears Eva say. And the voice in his head screams louder.

It screams for a minute. An hour. A century. All while Kenji is throttling back a scream of his own as his muscles twitch and seize.

Eventually, it stops. Kenji’s left crouching, shivering, elbows on his knees, head in his palms. He glances up and finds Eva, crouched beside him, worried.

“Let’s run away and never come back,” he rasps.

Eva doesn’t reply for a heartbeat. “Let’s go home first.”

They almost make it back without issue.

Then they see the funeral.

There’s a small raft and a small crowd at the banks of the Endless River. And it’s obvious, even from their viewpoint on the road, that the deceased man’s voice has died. He’s glowing so brightly it almost hurts to look at him. The deceased himself, though, is still alive. He thrashes against the bonds that hold him to the boat, cursing, shrieking.

“Betrayer,” Kenji’s voice hisses, still hoarse from screaming.

The mourners are stiff, circling, shielding the boat from onlookers as best they can. Their focus is fixed upward, praying toward the vaulting World above them, faces illuminated by the doomed man’s glow. As the seconds wear on, the voiceless man’s anger melts into tearful pleas.

Kenji doesn’t want to see this. But he can’t seem to will his feet to move. Can’t seem to look away. He keeps hoping that one of the mourners will have mercy on the voiceless man and free him.

No one does.

The prayers end and the boat is pushed off, without ceremony. The crowd of mourners disperses moments later; only a few stay to watch the River drift the dead man’s boat to its center and sweep him and his weeping away.

“He deserves it,” his voice whispers, and Kenji hears the unspoken threat.

Kenji doesn’t quite run home, but almost. His pulse is thumping, his teeth clenched. He hears Eva keeping pace behind him, but he doesn’t look back. He can’t.

Only when they’re in their apartment, safely alone with the door shut and locked behind them, does he turn to her and say: “How do I get a new voice?”

“So, you’re probably going to hate me for this.”

Eva was standing in the doorway of their living room, arms crossed, a smile playing on her lips. At this point, they’d been together for two and a half years. It’d been half a year since Kenji made his first piece of paper, and they had just moved into their new apartment a few weeks ago, though it was already covered with the detritus of their various projects.

“Probably,” Kenji said, and grinned. He was sitting on the empty living room floor, surrounded by buckets of slurry, his deckle and mould, and a dozen trays full of drying paper. He was trying a new slurry mixture, hoping it would make the paper studier. For the first time in his life, his voice—or his friends and parents—wasn’t admonishing him for not being a better artist. It was freeing.

“You know how much I love you, right?” Eva said, crossing the distance between them and resting her chin in the crook of his neck.

“Oh shit, coercion. Definitely going to hate you now. What’s your idea?”

He felt Eva smile against his neck. “A paper sculpture. A huge one.”

Kenji looked at the mess of half-made paper around him. He suddenly knew what he’d be doing for the next few months. He smiled. “Of what?”

“A First Givers’ ship. As close to life as possible, pointing upstream. Based on historical accounts.”

Kenji’s heart puffed up, threatened to burst. He’d shown Eva all the information he’d ever found about the First Givers, because he was fascinated by history. And she’d actually read it.

“Why upstream?” he asked.

“Why not?” Eva replied, swirling her fingers in a bucket of slurry. “They entered this World, so doesn’t that mean it’s possible to leave, too?”

“No,” said his voice. “That’s absurd. Don’t even think about it.”

But Kenji was already planning, dreaming.

The next morning, Kenji and Eva borrow a boat and go upstream.

Kenji has always hated going upstream. There is a darkness there that reminds him of all the terrifying stories his parents told him about the fabled Maw. Stories that his voice would repeat back in menacing tones for weeks afterward.

They pass another funeral as they row. But this time, the body is lifeless, not just the voice. The deceased’s skin is dull and dark. There is no stony determination in the faces of the mourners. Only grief.

Eva and Kenji nod respectfully as they pass, but don’t offer condolences. The deceased looks peaceful in her boat.

May we all be so lucky in death, Kenji thinks. He leans harder into his oars.

They keep rowing. Hours pass. The Endless River earns its name.

On the edge of civilization, Eva steers the boat into one of the many empty moorings. The buildings on the shores are smaller, shorter than the ones in the center of the colony, the art larger and more playful, freer from criticism. These are the last strands of settlement before the land gives way to the truffle and tuber farms.

And what’s past the farms? Kenji wonders.

“Nothing. Nothing’s there,” his voice hisses. The unrelenting darkness he saw as he looked upstream discouraged any other questions.

Without hesitation, Eva steps up to one of the sturdy homes and knocks on the door.

“How did you find this place?” Kenji asks. He grips his elbows to stop himself from fidgeting with nerves. Until yesterday, he’d never heard of a voice replacement. Doubts still haunt him.

“You’re not the only one who asks dangerous questions,” she replies.

“Wait, your voice isn’t dying, too, is it?” he asks, panic rising. His own death he could swallow, but not Eva’s.

“At this exact moment? No, no yet.” Eva knocks again, louder.

Before Kenji can reply, the door opens. The woman standing there is like her home, short and stout, and her clothes are neat if a little muted. She glows moderately, modestly.

“So soon?” she asks when she sees Eva, her eyes wide with surprise.

Eva shakes her head. “Not me. Him.”

The woman’s gaze pivots. “And who are you?”

“My partner. The love of my life,” Eva replies. “Kenji.”

The woman studies him for a moment and then sighs. “Right, you mentioned. An inventor, but not an artist. You should probably come in.”

She calls herself Caro. Her house is sparsely decorated; there’s almost no art. Which is jarring to Kenji, but also a relief. Her office is practical, with comfortable tuber-wood chairs. In the next room over, a girl of five or six is sprawled out on the floor playing with a small army of toy musicians.

Caro perches on her desk. One of Eva’s sculptures is in the corner of the room, a miniature of the First Givers’ ship. When Eva dies, it’ll be worth a small fortune.

“So, a new voice then,” she says.

Kenji hesitates. “You won’t . . . you’re not going to kill anyone for it, right?”

Caro grimaces. “I’m a mortician.” she explains. “Dying naturally is a bit more common out here. For example, a boy from one of the farms died yesterday. Mask wasn’t on right. Asphyxiated on spores.”

“And his voice is still alive?” Eva asks, hand on chin, leg tucked up under her. She is a portrait of ease and confidence. But Kenji knows better, sees her scarred left hand in a white-knuckled clench. The more worried she is, the calmer she tries to seem.

“Should be. They usually last about forty-eight hours or so,” Caro replies.

“And how many times have you done this exactly?” Kenji asks. Instinctively, his hand touches the back of his neck. The small lump there.

“Twice.”

“Both successfully?”

Caro shakes her head. “The first time, his replacement voice died anyway. Not sure why.”

“But the second time worked.”

“Yes. My daughter.” She glances over at the other room. The girl doesn’t notice them, happily chatting to herself.

Kenji tries to keep the shock off his face. In this World, you’re born with the voice in your head. It grows up with you, adopting the mannerisms of parents, teachers, friends. But Kenji never heard of a voice dying in a child before.

He’s beginning to suspect he hasn’t heard of many ugly things that happen in this World.

“Experiments are dangerous,” the voice in his head whispers.

Kenji closes his eyes. Fifty-fifty odds; he’s never been so terrified. But then he imagines himself, glowing brilliantly, tied to a funeral boat, floating helplessly downstream. He still has so many questions he wants to ask before he goes.

“Okay,” he says.

He feels Eva fingers squeeze against his, keeping him anchored. Keeping him steady and here.

She drew her idea for the sculpture on the wall of their living room. The first of many sketches to come. She drew a person next to it for scale.

“Holy shit,” Kenji said when he realized the size of the creation Eva was planning.

“Hate me now?” Eva asked with a touch of uncertainty.

He draped an arm around her shoulders. “Never.”

“I need to make a smaller-scale version first,” she said, and made a face. “Hopefully, they take me seriously this time.”

Eva’s first meeting with the Public Areas Committee hadn’t gone well. When she presented her earliest sculptures using Kenji’s paper, they told her competition for space was tough. But they’d been staring at her scars when they said it.

They had been together long enough that Kenji had seen the way people recoiled slightly in the street when they spotted Eva’s hand or face. He’d seen how her parents wouldn’t meet her eyes. As if her scars were a reflection of her character or the beauty she could produce.

He understood now why Eva had been reluctant to return to shore when they first met.

“They’d be idiots to turn down one of the most promising artists of our generation, again,” Kenji said. Eva hmphed, but she didn’t deny it. Her paper sculptures were like nothing the colony had seen before, and people were beginning to notice.

“I want to show the First Givers trying to leave,” Eva said.

Kenji’s voice whispered, “Why would you ever want to leave?”

He could think of a few reasons, but the thought was followed quickly by anxiety.

“Are you going to add teeth marks from the Maw?” Kenji asked. The World’s mighty Maw was the fuel of legends and nightmares.

“Don’t know yet,” Eva said, tapping her chin. “What if the Maw is just a story?”

“What if it’s toothless?” Kenji replied. His voice muttered its disapproval. But Kenji had lots of practice ignoring it now. Especially if doing so made Eva smile.

But the voice in his head had a point.

“The committee isn’t going to like anything that paints the World as less than benevolent.”

Eva’s jaw clenched, but her eyes glimmered. “Well, I’ll just have to be clever about it then.”

The slimy, eel-like thing in his hand was once the voice in his head. Kenji stares at it in horror, in fascination. It’s about the width of two fingers, and it’s cold, gray, and lifeless. He flips it over with a knuckle, then holds it closer, curious.

It takes him a moment to see it. The small mouth. And the hundreds of needlelike teeth within it.

Kenji gasps, recoils, and the dead voice slips from his fingers and goes tumbling under the bed. His hand shoots up to the nape of his neck and he feels a neat row of stitches. The whole surgery was painless, senseless, dark. Whatever mixture of mushrooms Caro gave him, it was effective.

But something isn’t right. His head feels too quiet. Empty.

“There’s a new voice in there, right?” Kenji asks.

Caro nods.

“Maybe it just needs some time,” Eva says. She’s sitting cross-legged on a chair beside him, waiting. Her hands are tight, white-knuckled fists on her knees.

Kenji tries to stand, but the world spins and his legs refuse to hold him. Two pairs of hands catch him and set him back on the bed like a child.

“It’s probably going to be another day,” Caro says, “or two before you can go home. This is still an experiment.”

Kenji starts to nod, but spikes of pain shoot up his neck. He gasps, his vision blurring with tears. He takes a deep breath and forces himself to focus on Caro’s daughter, who’s watching him from the foot of the bed, whispering to her voice.

“Maybe it just needs time to heal,” Eva says again.

“Yes,” Caro replies. But uncertainty threads her voice.

“If this works, it will stay alive for a long time, right?” Kenji asks.

But Caro doesn’t meet his eye, doesn’t answer. She’s worrying her lip and watching her daughter, who has wriggled herself under the bed, perhaps in pursuit of the slimy dead thing that was once Kenji’s voice.

For the moment, the girl has gone silent.

“Do you ever wonder why no one in the colony ever invents anything new?” Kenji asked Eva one night as they lay bare in bed, Eva’s head on his chest, his arm around her. They had fought earlier that morning about Eva’s new sap glue, which stank up the apartment like rotting fish, and Kenji’s ever-growing chaos of tools and mushroom pulp in the living room.

But now, post lovemaking, that fight seemed ridiculous. They were working toward the same goal. In a workshop, not far from them, Eva’s sculpture of the First Givers’ ship was growing.

“All the time,” Eva replied. “There should be more people like you. Like us.”

“Nonsense,” his voice whispered. Kenji swallowed, kept his eyes fixed on the ceiling.

“I’ve started this new research project. I’ve been going through histories of art galleries and comparing them with public records of the artists. And . . .” Kenji trailed off.

Eva propped herself up on her elbows and narrowed her eyes. “What did you find out?”

“It just seems like every artist who ever tried to learn more about how the World works or study history deeply ended up dying young.” He said this in a whisper. It felt like an ugly, terrible secret.

“Body or voice?”

“Voice,” Kenji said. “Always voice.”

Eva chewed her lips, and Kenji worried a strand of her hair in his fingers. He knew what she was thinking. The public had started calling them “The Experimentalist and Her Inventor.”

“There were a few accounts of some of these people deciding to go upstream instead of down,” Kenji said eventually.

Eva tilted her head with newfound curiosity. “Why?”

“Don’t know. One artist left a note saying she was looking for a way out of the World.”

“Huh. Wonder if she found it.”

Eva put her head against his chest again. She didn’t speak for a few moments. Kenji could feel her heartbeat and could almost feel her mind turning over this information.

Kenji tried to imagine what it’d be like to travel upstream, past the colonies and mushroom farms. But then he imagined the deep, consuming darkness past civilization and could go no further.

For the first time in his life, Kenji’s voice doesn’t admonish his curiosity as he wonders about dead voices and curious artists. Neither does it scream. It doesn’t say anything at all.

Caro was right: another night of sleep has made him feel more human. His neck is stiff but bearable. Still, he’s grateful to be rowing with the current as they steer their boat home.

As they drift downstream, they pass fishermen on piers, farmers on barges full of shiitake and portobello caps, painters on rafts trying to capture the light on the water. They pass no funerals. For that, Kenji is grateful.

By the time they get home, they are both exhausted and sore. They feel like they’ve outrun an enemy, and are on the verge of collapsing or celebrating, though Kenji can’t say if it’s from relief or nerves.

His new voice still hasn’t said a word.

He splurges on a whole fish for dinner, beautiful and silver, a rare find in the Endless River. He lies to the fisherman and says it’s for their anniversary. Truthfully neither he nor Eva remembers which day they started calling each other partner. From the day they met in the middle of the Endless River, they simply fell into each other’s lives.

As Kenji and the fisherman haggle over the price, just at the edge of the River, a funeral boat drifts by. The voiceless woman in it isn’t screaming. Just crying miserably. Her unrelenting brightness shimmers across the water, and both Kenji and the fisherman fall silent.

“I hope if my voice ever dies, I’ll have the strength to walk away myself,” the fisherman says quietly.

“What do you think is downstream?” Kenji asks, before he can stop himself. Dangerous questions, he knows. He waits to hear the voice in his head tsk him for wondering.

But there is only silence.

“Nothing,” the fisherman replies. He says it in that same condescending tone that Kenji’s old voice used to use.

Kenji tries again. “What do you think is upstream?”

His voice doesn’t reply.

The fisherman stiffens, suspicion blooming on his face. “You’re inquisitive, aren’t you?”

Kenji sighs. “So I’ve been told.”

Later, as Kenji cooks the fish, he asks Eva what she thinks is at the end of the Endless River.

“Nothing good.” She’s turned away from him, sketching a new sculpture concept on the living room wall. She refuses to use his paper for her first and roughest drafts, insisting she can’t defile his beautiful work with her ugly starter concepts. Instead, they repaint the living room walls every month or so. “It’s convenient that no one ever comes back, though.”

“Yeah,” Kenji says, and flips the fish in the pan. “Does . . . does it scare you, Eva?”

Eva twists so she can meet his gaze. “Terrifies me.”

They eat alone, each of them lost in their own thoughts and worries. Until Eva inquires casually about his new voice.

“Well, I never thought I’d miss its judgy commentary,” he tells her.

She cocks an eyebrow. “You let it talk down to you?”

Kenji blushes. “Doesn’t yours? When you wonder about dangerous things?”

“It used to.”

“How’d you get it to stop?” he asks, stunned. Everyone always said your voice was the soul of your art.

“I yelled back at it until I realized it didn’t have any power over me,” she replies.

That surprises Kenji for a moment. It’s a very Eva solution. “Oh,” he says. He has never once considered arguing with his voice. “Why?”

She glances over at the sketch she made on the living room wall. The drawing of her newest sculpture is vague, but the Maw and the figure standing in it is clear. No, Kenji realizes, the figure’s not in the Maw.

It’s on the other side of it. Outside.

If Kenji is judging the scale right, this piece will be larger than the First Givers’ ship.

Eva says: “Don’t know. It just felt like my voice was leading me down the wrong road.”

Two weeks before Eva’s sculpture was to be unveiled in the historic district, she strode into their bedroom, raging. “They won’t let me add your name as a sculptor! It’s bullshit. This piece belongs to you, too.”

“I’m not upset,” Kenji said as he continued to hang long strips of paper from their bedroom windows. And he wasn’t. Or surprised.

“Well, I am,” she replied, flopping on the bed. She stared at the ceiling, frowning. “They claimed the piece was provocative enough without adding a nonartist. Even though I added the kid on the ladder.”

That had been a late-stage addition. The child on the ladder, reaching up to touch the ceiling of the World, as if in reverence. Drawing the eye away from the deep gashes on the ship and the direction it pointed.

“Honestly, I’m surprised we got this far without getting in trouble,” he said.

Eva pushed her hair off her forehead. “I’m not. You invented something amazing and useful and I made new art out of it. We’re valuable members of the community now.”

“If you say so.” Kenji came over and flopped on the bed next to her.

“Do you ever wonder what will happen when we ask one too many questions? We’re going to. At some point,” Eva whispered.

“Yeah, we will.” Kenji took her hand in his. “I can make a pretty good guess.” He touched the back of his neck, where there was a small raised mound. “Question is: What will we do when our time comes?”

Kenji stands naked in front of the bare spot in their living room, the flesh of the World, curtain crumpled in his hands. It’s been a week since the operation, and his neck is still a little stiff from Caro’s handiwork. He’s glowing with a fierceness. All those nutrients that aren’t his to keep.

The new voice in his head still hasn’t said a word.

They say you need your voice to give back to the World. Now, he supposes, he’ll find out.

Eva paces behind him, biting her thumb, worry lines crisscrossing the scars on her face. Kenji inhales, places his left ankle against the flesh. Then his right. Eases back, slowly, carefully, he nestles his head into the warm, gray, living tissue.

The World shoves him away. The strength and ferocity of it takes Kenji by surprise. He lands badly on the living room floor, sprawled out, stunned. Through a fog, he hears Eva swearing, feels her wrapping him in her arms.

“This is bullshit! We’ve done everything the World asked!”

Kenji can’t breathe. Despair falls on him suddenly, crushing him like an avalanche. Even through the strength of Eva’s embrace, he feels her shaking. They stay like that for a long time.

Finally, he says: “You should give back. I’ll wait for you in the bedroom.”

“Like hell.” She holds him tighter.

“Eva.” He takes her hands in his. “They’ll strap you to a funeral boat, too. That will kill me.”

She resists, holding him tighter, for one moment longer. Then she relents, her shoulders sagging. “Fine, but I’m going to see Caro in the morning. We’re getting you another voice.”

That night, they make love like a long goodbye. It’s difficult to stop, to let go. It’s impossible to hide any emotion on their faces in Kenji’s too-bright glow.

Kenji’s tracing her ribs, studying every line of her face, etching each detail into his memory, when he says, “Promise me that you’ll keep on making art as long as you can. You are one of the only artists doing something unique in this World.”

She’s studying him with the same intensity. Kenji can almost see her drawing his face in the sketchbook of her mind.

“You know what bothers me most about my sculpture in the historic district?” she says. “People fixate on the kid, but that’s not the important part.”

“What is?”

Eva doesn’t answer.

The next morning, Eva goes to Caro’s house to see if anyone died recently. She returns by evening, with the slam of the door and an angry scowl. Kenji isn’t surprised, but his heart sinks anyway.

“She said maybe in a few days.”

So they wait. Kenji battles his nerves by making as much paper as he can. If this is going to be his last contribution to her art, he wants to leave Eva a princely gift.

In contrast, Eva pours herself into the sculpture concept on their living room wall. The Maw grows unforgiving teeth, shredding the little glowing figures that are trapped inside. Except for the two figures that stand beyond the Maw, nothing escapes. It is not an image of a gentle, benevolent World.

This piece is going to upset a lot of people. But Kenji suspects that’s the point. It’s as if Eva’s baiting her voice into dying, too.

Kenji aches to tell her to stop being so reckless. But he fell in love with her because she was the only person he’d ever met who was more curious than he was. He stayed in love because she never stopped asking dangerous questions.

And right now, as he watches her, full of her anger and her courage, he loves her fiercely.

The days pass, and Kenji grows brighter. He glows through the thin walls of their apartment. The neighbors begin knocking on their door, first with concerned looks on their faces, then wary ones. Eva keeps them at bay with lies, something about a new art concept she’s working on. It’s a flimsy excuse, and Kenji imagines a malevolent crowd growing daily outside their door.

They can’t stay here much longer.

That night, they steal away in a boat. Even wrapped in all the clothes he owns, Kenji’s traitorous skin shines through the layers. He hurries, grabbing the oars, as Eva pushes off.

But there is no place in this World for the voiceless.

They spill onto the pier like spores. Their neighbors, friends, and fellow artists. They rush up on the pier and grab at Kenji’s layers, shouting, “Given! Give back!” The funeral mob glows, but not as brightly as him.

Kenji pushes back, but the mourners are as greedy as the World. Their fingers tear at him. Their voices ring in his ears. His glowing skin illuminates their angry, frantic faces.

Kenji swings his oars in wide, defensive arcs, stumbling into the belly of the boat, buying Eva time to pull the boat into the water.

It works. They escape the grasping hands and begin to drift with the current.

All while voices on the pier are screaming, screaming, screaming.

Something hits the back of his head. Hard. Suddenly, his legs won’t hold him. Suddenly, there’s water around him. It’s icy and dragging him down.

He feels Eva grab him by the necks of his layered shirts. He tries to tread water, but it’s cold, so cold. And the World has become blurry and vague.

He hears Eva shouting: “No! No yet!”

He tries to fight, but he can’t feel his hands, his legs. All he knows is water, brackish and frigid, and the way his body is being pulled and carried by the current, by hands. He knows the taste of mushrooms, this acrid, earthy blend.

Then he knows nothing at all.

“What do you think is outside of the World?” Kenji asked, the night before Eva’s sculpture was unveiled.

“Nothing,” his voice hissed.

Eva took a bite of her dinner, a portobello-and-eel skillet, and considered the question. “It could be anything, really. What if there’s other colonies, but they all live in ships like the First Givers?”

“What if there’s only mermaids left?” Kenji replied.

“Or only poisonous mushrooms?”

“Or only the most generic folk tunes?”

“Oh, that would be terrible,” Eva said in mock horror. “Maybe this isn’t so bad then.”

“Yes,” said his voice.

Kenji stabbed a piece of eel on his plate, thinking of the Maw. “Maybe we can just be happy here, making groundbreaking art.”

Eva smiled from across the table. “Yeah, maybe we can.”

The pain in the back of his neck is familiar. That’s the first thing he notices.

The second thing is that he’s been in this bed before, this room. Caro has covered the walls with thick, dark curtains, and he hears her daughter playing in the other room. Kenji groans, turns, expecting to find Eva sitting on the chair beside him.

He finds Caro in the seat there instead.

“I’m sorry, Kenji,” she says. She looks tired, pale, deeply sad. “I tried to convince her to stay, at least until you woke up.”

Fear constricts Kenji’s chest, making it hard to breathe. With a shaking hand, Kenji touches the base of his neck. There are fresh stitches there.

“Whose voice did you use?” he asks. Barely above a whisper.

The voice in his head says: “She never stopped asking questions, either.”

Kenji gasps, knowing then, heart breaking with the answer.

It’s Eva’s voice.

The day of the unveiling, Eva and Kenji stood side by side a little apart from the swelling crowd. It felt like everyone in the colony had come to see this massive paper sculpture. They circled around it, openmouthed or talking in awed tones as they reached out and touched the creamy white paper, the likes of which were only First Givers myths before this.

“I think you’ve made an impression,” Kenji murmured to Eva.

“Shit, they’re focusing on the kid on the ladder,” Eva said, frowning. “That’s not the point.”

“What is?”

Eva shook her head.

“Some people will get the message. The ones who look a little closer,” she said.

“Maybe one day, that’ll be me then,” Kenji joked.

Eva smiled at that and took his hand in hers.

“Maybe it will.”

Eva is gone.

Caro apologized over and over. She hadn’t wanted to use Eva’s voice, but Eva was so frightened as she carried an unconscious Kenji into her house. Eva was so stubborn. Her voice fought the whole time. And Caro had been so nervous performing the operation, this dangerous new science, that she didn’t realize Eva slipped away while she was working on Kenji.

“I just want to learn how to save people like my daughter,” she says. “I want to leave something better than art behind.”

Kenji understands. All too well.

A few days later, Kenji leaves Caro’s house, climbs into their boat, rows to the center of the River, where the World goes silent, and lies down. Where did she go? he wonders.

“She’s gone,” her voice whispers.

“Says you,” he replies with a scoff. Why didn’t she tell him where she was going?

“Because you were holding her back,” her voice replies. And for a moment, Kenji’s battered heart aches with the possibility.

“Stop lying,” he says through clenched teeth. “Or I’ll cut you out myself.”

Her voice hisses but doesn’t respond.

He allows the boat to float downstream to the historic district, to where Eva’s sculpture is.

He docks at the nearest pier, climbs out, and approaches the masterpiece.

But without Eva, no one notices him. For the first time in years, he’s able to study every crease and wrinkle and curve of the sculpture in peace.

This is how he finds the answer.

At the base of the ship, among the crowd of paper people, two paper children stand slightly apart, not looking at the ship but at something else far in the distance. One’s pointing upstream, in a determined, adventurous stance, and Kenji notices half of her face is creased and ridged. The other is next to her, following her line of sight, holding a clean sheet of paper in his hands.

And Kenji knows then. He knows exactly where Eva went.

With a smile, he climbs back into his boat and turns it against the current.

Eva and all his answers are upstream. They always have been.

Eva’s voice begins to scream. It screams at him to stop, it screams at him to turn around, to obey. But Kenji is no longer afraid of the World, and even at its loudest, the voice in his head has become small, powerless.

Kenji laughs as he starts to row, pushing forward into the darkness, into the great, swelling unknown.

Buy the Book

Questions Asked in the Belly of the World

“Questions Asked in the Belly of the World” Copyright © 2021 by A. T. Greenblatt

Art copyright © 2021 by Rebekka Dunlap