This past summer, Netflix took fans back to Fear Street with a trio of films: Fear Street 1994, Fear Street 1978, and Fear Street 1666. While there are significant differences between the two iterations of Shadyside, both R.L. Stine’s series and these films are deeply invested in the horrors of history and the Gothic tradition of a past that refuses to stay buried.

Leigh Janiak, who directed all three of the Netflix films, has made it clear that her adaptations aim to be true to the spirit of Stine’s books rather than follow any specific narrative from the author’s series, which is ideal for creating new stories for a contemporary audience and amplifying representations that were marginalized, silenced, or absent altogether in the pop culture landscape of 1990s teen horror.

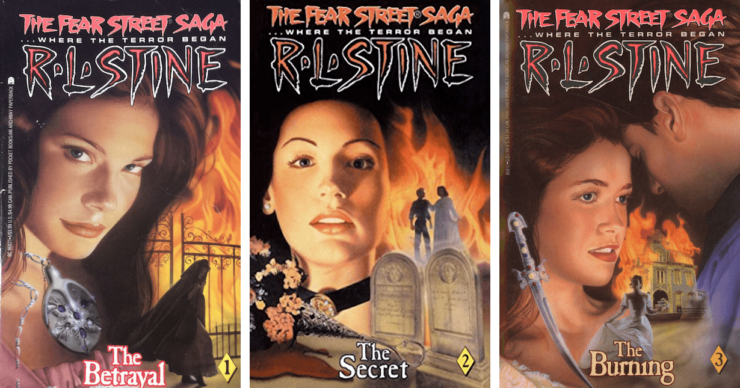

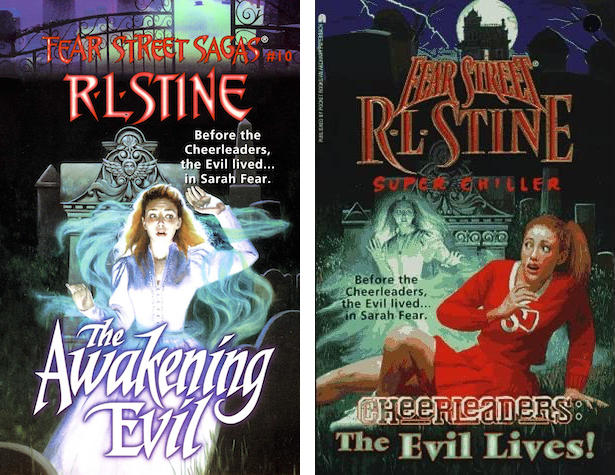

There are a few of Stine’s Fear Street books that are particularly useful in considering the role of horror and history on Fear Street. First, there’s the original Fear Street Saga trilogy—which consists of The Betrayal, The Secret, and The Burning (all published in 1993)—whose cover tagline promises to tell readers “where the terror began,” tracing the Fier/Fear family’s history back to 1692. The Awakening Evil (1997) and Cheerleaders: The Evil Lives! (1998) are part of Stine’s larger Cheerleaders sub-series, which follows the misadventures of Shadyside High School’s cheerleading team, whose members repeatedly become possessed by and fight a timeless evil. (The Awakening Evil is also the tenth installment of Stine’s Fear Street Sagas, a historical fiction sub-series within the larger Fear Street universe).

In addition to the Gothic tradition of the interconnections of the past and the present, another common thread between Stine’s books and Janiak’s films is the role of storytelling itself, including who gets to tell the story, what gets recorded (and what gets forcibly erased), and how that story is transmitted, with a range of unconventional means of transmission, from hallucinations to time travel.

Beginning with the Fier family’s history in Wickham Village, Massachusetts Colony in 1692, Stine’s The Betrayal sets a pattern of desire and destruction that characterizes the relationship between the Fiers and the Goodes through the centuries and follows them to Shadyside. Benjamin Fier is the village magistrate and he and his brother Matthew hold privileged positions within the colony, despite the fact that where they have come from and how they have come by their power remains a mystery to their fellow colonists (surprise: it’s evil magic). Benjamin is particularly elevated—and feared—in his role charging and persecuting witches. When Benjamin’s son Edward falls in love with Susannah Goode, a kind but poor young woman in the village, it is all too easy for Benjamin to plant evidence, charge Susannah and her mother with witchcraft, and have them burned at the stake, paving the way for a more socially and financially advantageous marriage for Edward. Echoing the social dynamics and gendered persecution of historical witch trials, the Goode family is unable to stand against the Fiers, proved by the fact that William Goode pays Matthew Fier’s blackmail price for his wife and daughter’s freedom, and Susannah and Martha are burned at the stake anyway. In an interesting twist, William Goode is just as adept at dark magic as the Fiers and swears his vengeance, pursuing them and bringing death and destruction wherever he encounters them.

And so begins the feud between the Fiers and the Goodes, with each teaching their children and grandchildren that the other family are their sworn enemies, starting a never-ending cycle of star-crossed love, revenge, retribution, and death. Both families have victims and villains, with the hatred between them fostering further violence. The Fiers have a magical medallion (stolen from the Goodes) inscribed with the motto “Power Through Evil,” which bring wearers hallucinations of the fire that is destined to destroy them. The spirit of Susannah Goode burning at the stake also haunts the Fier descendants. The story of these two families is told incompletely through these fragments as it passes from one generation to the next. (Along the way, the Fiers change the spelling of their name from Fier to Fear when a potentially witchy old woman points out that Fier rearranged spells “fire,” foretelling their family’s doom. “Fear” doesn’t really seem like a safer option, but it’s the one they go with anyway).

The frame narrative of the trilogy and the voice through which the story is told is that of Nora Goode, who is institutionalized following her ill-fated marriage to Daniel Fear—which lasts less than a day before he dies horrifically—and the fire that destroyed the Fear Mansion. After staying up all night feverishly committing their two families’ dark histories to paper, her account is taken from her and burned as she is hustled out of her room to see her doctors. The story she has worked so hard to tell, the hundreds of years of intertwined family histories she has chronicled, and the trauma she has persevered through to make sure the truth comes out are completely eradicated as she is pathologized and stripped of her agency. The novel ends with talk of the construction of Fear Street and the reader’s knowledge of the story that has been silenced, which will act as the foundation for all of the evil to come.

In The Awakening Evil and Cheerleaders: The Evil Lives! Stine turns to the story of Sarah Fear, who also becomes a key figure in Janiak’s trilogy of films. These are the fifth and sixth books in Stine’s Cheerleaders sub-series and up to this point in the overarching narrative, Sarah Fear herself has been largely defined as the evil that possesses and destroys the cheerleaders. However, The Awakening Evil rewrites Sarah’s story, revealing her as a victim of the evil itself in her own time (1898) … and as not really Sarah Fear, exactly.

Technically, there is no Sarah Fear. There are two young women named Sarah Burns and Jane Hardy. Sarah is arranged to be married to Thomas Fear but would rather live independently and travel the world, while Jane longs for marriage and a family. So they switch places and Jane marries Thomas and becomes Sarah Fear, while Sarah Burns boards a ship bound for London, which sinks, killing everyone onboard. Motivated by her rage and the perceived unfairness of her fate, Sarah Burns becomes the evil that stalks the Fear family, possessing Sarah Fear and making her commit horrific murders. Sarah Fear is a victim of Sarah Burns’ evil, but she also becomes a hero, drowning both herself and the evil within her in an attempt to protect her niece and nephew.

In The Evil Lives!, the modern-day cheerleaders negotiate this story through a range of different storytelling modes, including the note one of the original cheerleaders, Corky Corcoran, leaves telling them not to summon the evil (which they of course do at the first opportunity) and the local legends and ghost stories that vilify Sarah Fear. One of the cheerleaders, Amanda Roberts, is transported through time to witness Sarah and Jane switching places and later, the sinking of the ship that kills Sarah Burns.

In both the Fear Street Saga trilogy and the last two books of Stine’s Cheerleaders sub-series, the past and the present can never be truly separated from one another, in large part because the past is fundamentally misunderstood. In the Fear Street Saga, the Fiers/Fears and the Goodes each tell their descendants a single version of their families’ story, in which they have been wronged and must seek vengeance, further fueling the flames of hatred through this half-told story, highlighting the significance and limitations of subjective perception. In the Cheerleaders novels, Sarah Fear has been turned into a kind of Shadyside boogeyman, with the stories that are told and retold presenting her as unquestionably evil, rather than the complicated combination of victim, villain, and hero she actually was, a misunderstanding of the truth that allows the evil to reign unchecked. This erasure is particularly damaging to women, who fall into stark dichotomies of victimized heroines or evil vixens, silencing their more complex stories, their experiences, and the violence that has been committed against them. In each of these stories, how the story is told—or perhaps more accurately, experienced—is essential as well, with true understanding coming through hallucinations, visions, and time travel, rather than the incomplete histories that have been recorded and the flawed stories that have been passed down.

Janiak’s Fear Street films follow a similar pattern of combining the sins of the past with the terrors of the present, with Fear Street: 1994 and Fear Street: 1978 presenting Sarah Fear as the clear villain of the story, responsible for the undead horrors that stalk, murder, and possess Shadyside’s teens. Shadyside’s execution of Sarah Fear as a witch in 1666 continues to reverberate through their town and in the very land itself, in the complex series of subterranean caverns that underlie Shadyside. But as with the feud between the Fear and Goode families and the legacy of Sarah Fear in Stine’s novels, this understanding is flawed, manipulated, and designed to marginalize and silence Shadyside’s least privileged citizens, both then and now.

As with Stine’s novels, the process of storytelling is central to Janiak’s Fear Street films, from the visions of Sarah Fear that several characters experience, the teens’ conversations with characters who endured earlier cycles of this violence, and the overt questioning of the dominant narrative that has shaped Shadyside. For example, as the teens question C. Berman (Gillian Jacobs/Sadie Sink), one of the only people who has lived to tell her story of being attacked by the monsters of Shadyside, they collectively realize the truth that has been suppressed for generations, as generations of Goodes have shaped and manipulated the story of Shadyside for their own dark advantage. Similarly, when Deena (Kiana Madeira) essentially becomes Sarah Fear through a hallucinatory flashback, she realizes how completely Sarah has been robbed of her own story, which has been co-opted by powerful men who sought to silence her and who, after her murder, recast her as a monster. Additionally, each of Janiak’s film’s taps into and draws upon a specific horror film moment and aesthetic, as 1994 follows the patterns of the mainstream teen horror films of the 1990s, 1978 follows classic slasher film conventions, and 1666 draws on tropes of historical horror. With allusions and visual echoes of films ranging from Wes Craven’s Scream (1996) to John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), Sean S. Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980), and Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015), among others, the Fear Street trilogy draws on established tropes and traditions to tell a new story, reflecting on the different ways horror can be mobilized and how some terrors never change.

Most significant, however, is whose story gets told in these films. Teen horror of the 1990s was almost exclusively white. Any BIPOC character was a matter of note, and they were almost all peripheral characters. There were significant class distinctions, but these were rarely addressed in any substantive or systematic way. Characters all fit into a rigid dichotomy of gender identity. Everybody was straight.

Janiak’s Fear Street films put a queer woman of color right at the heart of the narrative with Deena, played by Kiana Madeira. Deena is a hero who rallies her friends to fight against the evil force that threatens them and when her ex-girlfriend Sam (Olivia Scott Welch) becomes possessed, Deena refuses to give up on her, fighting through seemingly insurmountable challenges, trauma, and near-certain death to save Sam. She interrogates and dismantles the stories she has been told her whole life to figure out what’s really going on and in saving Sam and herself, is able to avenge Sarah Fear as well. Deena stands against both the supernatural forces and real-world power structures that threaten to destroy her, and she emerges victorious.

Buy the Book

Nothing But Blackened Teeth

While Deena’s individual story is compelling on its own, Janiak’s Fear Street films also make the critical analysis of social and systemic inequities central to the narrative. Deena’s subjective experiences are her own, but they are also indicative of the larger culture which surrounds her. Deena’s family struggles to make ends meet but this is also a larger, cultural problem: Shadyside and Sunnyvale are polar opposites in terms of class and privilege, a difference that shapes the opportunities their children have, how they are understood, and how they are treated and interact with one another, which is showcased at the memorial gathering in Fear Street: 1994 and the rivalry at Camp Nightwing in Fear Street: 1978. But this is not a coincidence. Civic management and the unequal distribution of resources (and okay, dark magic) also contribute to and exacerbate this systemic inequality. When Sarah Fear is persecuted as a witch in Fear Street: 1666, she is not singled out at random or because she has performed any magic at all, but specifically because she is a queer woman of color, a “threat” that must be neutralized after she is seen kissing the pastor’s daughter and refuses to acquiesce to the settlement’s patriarchal rules and traditions.

Janiak draws a direct through-line between these time periods that makes it undeniably clear that the evil of Fear Street cannot be isolated to a single figure or moment—it is the direct result of the systemic inequality of the community as a whole. The Goodes may mobilize it, but whole communities surrender to and uphold its inequalities. These power dynamics determine who could be successfully accused of witchcraft in Fear Street: 1666, allow the Sunnyvale campers to abuse the Shadysiders in Fear Street: 1978, and shape the public perception of Deena’s friends following their murders in Fear Street: 1994. Each individual threat can be neutralized, each monster stopped, but these are really just distractions, red herrings to keep the people of Shadyside from looking too closely at the power dynamics that shape their town. After all, if you’re trying to survive being attacked by an undead ax murderer, who has time to lobby for substantive social change?

While both Stine’s Fear Street novels and Janiak’s trilogy of films draw on the interconnections between horror and history, Janiak adds new voices and more inclusive representation to these tales of terror, effectively identifying and addressing a clear lack in the films’ inspiration and source material. As both versions of Fear Street demonstrate, we need to look to the past and its shortcomings—whether in history or popular culture—to tell more inclusive stories, amplify previously marginalized voices, and create a better future.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.