The three-part essay “Excavating Unconquerable Sun” answers some of the questions I’ve been asked about how I adapted the story of Alexander the Great into a gender-spun space opera.

Which of the places and events represent real places and events from the past? How many of the characters are analogs for the historical actors? Why are modern (as well as historical) easter eggs worked into the text, some of which may seem wildly out of context or meme-ishly frivolous?

Transforming history into a fictional universe means the writer builds using a template of known events, places, and people. To begin with, when adapting real history into a fictional universe it is crucial to make sure any reader can enjoy the story without prior knowledge of the history. At the same time, a writer can weave aspects of the specific history into the story so readers who do know the history can catch references, allusions, asides, and jokes that play into or against what we know of the historical events and people.

Alexander the Great’s story is fairly clear-cut in its broadest outline. He was born over two thousand years ago in the kingdom of Macedon to Philip II and Olympias. In those days Macedon was seen by the culturally dominant Greeks as peripheral to the Greek world, and some ancient Greek politicians argued they were not true Greeks. Nevertheless, Philip, through conquest and negotiation, made himself hegemon of many of the Greek city-states and alliances. As king of Macedon, Alexander went farther than his father: he and his army conquered Persia, the great empire of his day.

In the ancient world, or at least among the Romans, he was declared the greatest military leader who had ever lived. Histories of his campaign and legends about his life proliferated for centuries as far afield as Persia, India, and Ethiopia. The Alexander Romance, more fiction than history, was one of the most popular stories during the European Middle Ages. New biographies of him are still published every few years. He is one of the best-known examples of an ambitious and successful young conqueror.

Once a speculative fiction writer has embarked on the march upcountry, many routes are present. Mine starts with Unconquerable Sun.

As a writer I started with questions: How much of the Alexander history do I want to leave intact as fairly direct narrative analog? How much do I want to alter and re-vision the people, setting, and events of the original story? Is it necessary for readers to be able to recognize the foundational story? Do I want to cleverly pack in details and themes derived from the original history that a knowledgeable reader can enjoy unpacking? Or is my intent simply to use the template as a rough guide without making it identifiable in the narrative?

Obviously there is no right answer to any of these questions. No two writers will filter the same historical events through the same speculative lens, and that’s how it should be.

My goal was to stay true to an idea of the historical Alexander while adapting where possible, and altering where necessary, the actual people, places, and events so they made sense within a space opera scenario. In addition, I wanted to honor and expand on the idea of a legendary Alexander whose adventures can reflect the concerns and interests of the contemporary audience who will be reading the story, just as did the medieval Alexander Romance with its many different episodes and fabulous adventures.

One of the most interesting aspects of Alexander the Great is the sense that he was the right person in the right place at the right time to accomplish what he did (whatever one might think of his campaign, good or bad). He is not an unencumbered Ubermensch perched atop the crag of history, poised to leap into any fray and win victory through the doughty sinews of his massive thighs and the daunting sledgehammer of his mighty intellect. Alexander is a product of his relationships with the world he was born into, the people he grew up amid and those he later came into contact with, as well as his understanding of his place in this landscape and history.

What did it mean to Alexander to be Macedonian and an Argead (Macedon’s ruling dynasty)? What role did the Greek city-states, especially Athens, and their long relationship with Macedon play in his understanding of the world? How did the Macedonians and the Greeks see the Persians, who ruled the greatest empire of its era, one of the first multi-cultural, multi-ethnic empires in human history?

To quote historian Carol Thomas: “To be sure, Alexander shaped the course of history by his own actions. At the same time, the nature of the world into which he was born shaped him to pursue his whirlwind career.” [Alexander the Great In His World, Carol Thomas, Blackwell Publishing]

Buy the Book

Unconquerable Sun

For this reason I chose to start my adaptation with the nature of a world—worlds, in this case—and the background of a history that could produce a character like Sun.

To do that, I began with two questions:

1. Which aspects of the main conflicts in the history do I want to retain while also creating a unique setting and background for the story?

2. Who is Sun (the main character and Alexander analog)?

It seemed useful to me to keep the three major players: the upstart Macedonians, the Greek city-states and their alliances, and the powerful and immensely wealthy Persian Empire. These three powers are clearly delineated from the beginning as the Republic of Chaonia, the Yele League, and the Phene Empire.

The history between these three political rivals follows a similar history to the real history because the real history creates good reasons why everyone distrusts everyone else and why Chaonia would choose to confront the much larger and more powerful Phene Empire now that it has the Yele League under control. The parallels aren’t exact, nor are they meant to be, but a vaguely historically familiar set of events have taken place in the past of the story in order to set up the present situation that opens chapter one.

The story references multiple other political entities and peoples, including the Hesjan cartels, the Gatoi banner soldiers, the hierocracy of Mishirru, the Hatti territories, Karnos (star) System, and the strategically crucial star system Troia.

These reflect historical analogs without being directly historical: The Hesjan cartels are a very rough placeholder for Thrace, kind of. The Gatoi are the roaming Celts, sort of. Mishirru stands in for Egypt (Misr), pretty much. The Hatti territories cover a lot of Anatolian ground (west and central modern Turkey). Karnos is a word broken out of Halikarnassos, a real place. In the text I say of Troia System: “On archaic beacon maps the Troia system is listed as Ilion, but after the Phene took over it began to appear on maps as Troia. A troia is an entertainer, a person who offers their services in a wide variety of capacities.” This of course is a play both on Troy and on the idea that under a long-term military occupation an entire eco-system of entertainment, sex, drinking and dining, gambling, and other such services would develop.

The history of the three major players is introduced at a basic level early on in book one. Its more complex aspects will unfold throughout the trilogy. For example, the Phene Empire is not a monarchy as the Achaemenid Persian empire was; its origins are radically different, and its current mode of rule is a central driver of the plot.

The single most significant change in the history and “geography” of the story past has to do with the space opera setting itself.

In the story, the human population (spread out through many star systems) is descended from refugees of a long lost Celestial Empire. These refugees fled this abandoned home world about four thousand years prior. I hope readers understand that the Celestial Empire is Earth, not that anyone in the story calls it that or has ever heard the terms “Earth” or “Terra”.

This aspect of the universe building isn’t based on the Alexander history. It specifically targets one of my goals for the larger story: the idea that we can only understand the past incompletely, through fragments and shards that don’t always make sense to us in the present day or that we may have mistaken for something different from what they really are.

Many of the names of planets, solar systems, habitats, and cities are taken from ancient history. This reflects the idea of people honoring an ancient past by naming their new homes after old places whose names have survived. It also is meant to suggest the fragmentary nature of the knowledge that has survived about the lost long home world. Think of it as a four-thousand-year-old archive of clay tablets, broken and scattered, from which a modern scholar must try to reconstruct names, places, history, and culture from across a vast distance with fractured evidence.

References to the Celestial Empire aren’t the only aspect of world building specific to the story while lacking ties to the Alexander history. For example, the Apsaras Convergence mentioned in the story does not reflect any historical place or people. It is part of the space opera setting because the Convergence were the creators and builders of a game-changing transportation method called the beacon network.

Within all this, who is Sun, besides being the Alexander analog? What aspects of the historical Alexander are most important to creating Sun’s story?

Alexander’s history is focused around war, battle, diplomacy, conflict, greed, power, treasure, and the complex interplay of ruling classes and competing political nations and factions. It can be problematic and arguably dubious, especially in these days, to focus a story on war when war is so destructive to so many aspects of life. But having decided I wanted to tell this story, I accepted that conflict and battle would be at its heart. Thus one of my goals as part of the story would be to recognize and illuminate some of the consequences for the often unseen people trapped in the path of conflict.

In terms of my main character, however, I asked myself what aspect of Alexander I most wanted to have Sun emulate. Given that I intended to gender spin the story, what aspect did I most want to highlight to reflect back on the original story?

As with Alexander, I felt Sun’s story would work best if she emerged from a dynastic line of rulers. Specifically, I wanted her to be part of a dynastic line in which gender isn’t a qualifying (or disqualifying) factor in inheritance.

As a man in the ancient world, Alexander never doubted his capacity to lead. In part this is because of his own supreme self confidence, but at root it is because the society he grew up in never questioned his right to become king after his father (factional disputes aside). He was a boy. Boys became men. Men became kings. Certainly I wanted to highlight ambition and self confidence as two of Sun’s defining characteristics. However, the aspect of Alexander I most wanted to depict in my space opera is the sense that the society around Sun also never doubts her capacity to lead. In our world today, it is still rare for women’s leadership not to be picked apart, questioned, and challenged. I wanted her personality to have developed within the same cultural assumption of competency and opportunity that Alexander received.

At the same time I wanted to complicate and interrogate the idea of monarchy in this far future.

Chaonia calls itself a republic. It has an assembly elected by all adult citizens, and it also has a palace in which lives an absolute ruler, the Queen-Marshal. Rulership in Chaonia is inherited but also earned in the sense that the ruler (as was true in ancient Macedon) must be able to lead armies in a political landscape filled with conflict. Because the Republic of Chaonia has been on a war footing for generations, the commander in chief of the fleets and the army is the head of the government. Thus the title of the ruler is that of marshal, not queen. As the character Zizou opines early in the story, “my teachers all said it is just a tyrannical military dictatorship.”

Every Chaonian ruler is addressed as queen-marshal regardless of gender because queen is the rank of marshal that the ruler holds as commander of the military. That is, a queen-marshal outranks a crane marshal, who outranks a kite marshal, who outranks a marshal. There is no tradition of kingship in the sense of rulership confined to or considered normal only among men, and there’s a reason for that, but you’re not going to learn it in book one.

There can be a danger in gender spinning stories. It is important, I believe, not to suggest that a woman can only be interesting if her story fits a traditionally masculine role because then we are still saying only men have interesting stories. Women’s lives throughout history and across cultures are just as worthy of story, even if we have often been told they are not.

As well, in many recent gender spun retellings, the story isn’t about giving a female character status and importance by making her a man or by giving her a traditionally male role. It’s about letting a narrative present not-male characters with the same qualities men have long been valorized for and which women and other marginalized and under-represented genders have always possessed but too rarely been allowed to express. It’s about creating a narrative in which an Olympias (Alexander’s mother) isn’t demonized for behavior that is excused or accepted if men engage in it. It’s about building a narrative that allows a range of positive and negative choices and traits to be unexceptional for anyone in a world where gender isn’t the defining social and intellectual and physical quality of an individual.

One of the great pleasures of writing this series is how it allows me to play with so many of the tropes and stereotypes that I grew up with as a reader. History can be remixed through a science fiction or fantasy lens to create a fresh angle for looking at familiar ideas and old, entrenched problems. Maybe also just for fun.

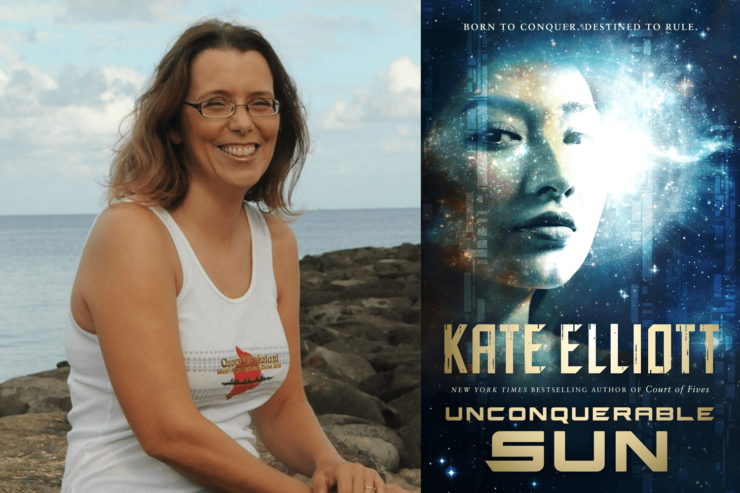

Kate Elliott’s most recent novel is Unconquerable Sun, gender swapped Alexander the Great in space. She is also known for her Crown of Stars epic fantasy series, the Afro-Celtic post-Roman alt-history fantasy (with lawyer dinosaurs) Cold Magic and sequels, the science fiction Novels of the Jaran and YA fantasy Court of Fives, and the epic fantasy Crossroads trilogy with giant justice eagles. You can find her @KateElliottSFF on Twitter.