A group of mercenaries is hired to deliver a church’s ultimate power—a sacred oracle…

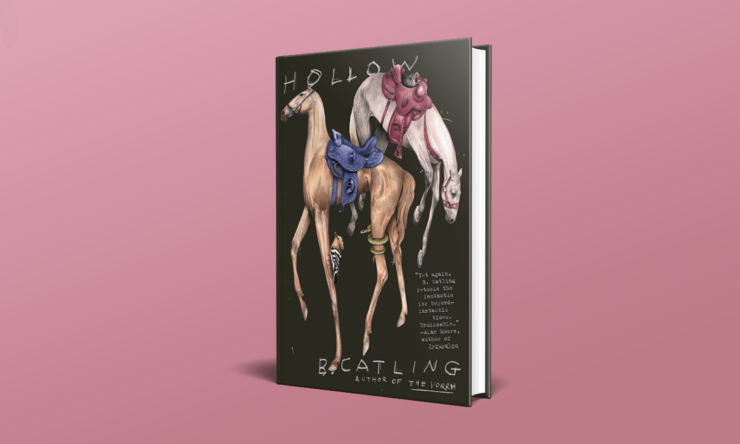

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Hollow, an epic odyssey from author B. Catling—publishing June 1st with Vintage Books.

Sheltering beneath Das Kagel, the cloud-scraping structure rumored to be the Tower of Babel, the sacred Monastery of the Eastern Gate descends into bedlam. Their ancient oracle, Quite Testiyont–whose prophesies helped protect the church–has died, leaving the monks vulnerable to the war raging between the living and the dead. Tasked by the High Church to deliver a new oracle, Barry Follett and his group of hired mercenaries are forced to confront wicked giants and dangerous sirens on their mission, keeping the divine creature alive by feeding it marrow and confessing their darkest sins.

But as Follett and his men carve their way through the treacherous landscape, the world around them spirals deeper into chaos. Dominic, a young monk who has mysteriously lost his voice, makes a pilgrimage to see surreal paintings, believing they reveal the empire’s fate; a local woman called Mad Meg hopes to free and vindicate her jailed son and becomes the leader of the most unexpected revolution; and the abbott of the monastery, influential as he is, seeks to gain even more power in this world and the next.

DOG-HEADED MEN

“Saint Christopher is a dog-headed man.”

The Oracle, bound in wet blankets, spoke for the first time with a voice to silence the angels. The eight men and their horses stood silently, paying close attention, while turning away from a ninth man, who hung in the tree above them, his face frozen in twisted pain. Scriven had been executed by the leader of this savage pack for the crime of writing.

Barry Follett would have let his victim stay where his lance had dropped him, but being eaten by wolves was considered a terrible fate, even if postmortem, so the men agreed he should be put out of the reach of wild animals. None of them cared enough to go through the motions of a real burial, and no one ever wanted to talk about the dead man again. So they strung him up in the branches of the nearest tree. The dense forests of sixteenth-century Europe were saturated with wolf packs. They had no fear of men, especially in the higher elevations and ragged mountains.

No one understood why Follett’s intolerance of writing had led him to kill this man, and now he had forbidden any discussion about what had occurred. Not that conversation had been rampant thus far in their journey. The snow and cold blighted all communication. No one had time for small talk or cared to hear what the others had to say. Only the strange words of the Oracle, which seemed instigated by the sudden violence, were worth heeding—and the men listened carefully before the wind snatched its words away, whisking their sound and their mystery into the eternal fury that squalled above.

The group had made it to the hard granite of the upper sierras, and its cracked, narrow paths were tighter and less forgiving than Barry Follett’s treacherous fist of a heart. Their leader sat alone on a bare rock above the gathering, silhouetted by a bright cold sun that stared down from the steel-blue dome of the sky. He was cleaning the head of his lance for a second time, while planning the route his seven ironshod pilgrims would take. He had hoped the first words the Oracle uttered would reveal his path; he was not expecting the inexplicable statement about a saint.

***

Follett had recruited his crew of mercenaries only months earlier, shortly after accepting the task to deliver the sacred Oracle to the Monastery of the Eastern Gate. His employers were the highest members of the High Church. They had summoned him, and he had consented only after being reassured that his potential employer had nothing to do with the Inquisition. Three solemn priests questioned him for more than an hour before nodding their agreement. One, an Ethiopian from a Coptic order, had been holding a small object during their meeting. He stood and held the precious thing so Follett could see it. It was a miniature, painted on ivory, showing a distant view of a vast mountain-like structure and its surroundings.

Buy the Book

Hollow

The oldest priest declared, “This is a depiction of your destination when it was known as the Tower of Babel.”

The black finger of the priest standing over Follett pointed at the tower, and he said, “.’Tis now called Das Kagel.”

A vast structure of spiraling balconies and stacked archways reached up to penetrate the clouds. A great movement of the populace speckled the enormous tower, while villages and townships crowded around its base, all balanced against a calm sea supporting a swarm of ships. The finger moved a fraction of an inch over the tiny painting to point more exactly at something that could not be seen.

“This is where you will find the monastery, and I should tell you the tower is changed beyond recognition. But you will know it by its profile and by the populace that infest the base. The Blessed One must be inside the monastery gates by Shrovetide, before the liturgical season of Lent closes the world and opens the mirror of Heaven.”

Follett cared little for Heaven and had never been near the Eastern Gate; few had. It was a shunned place that most men would avoid. Only a savage gristle of a man like Barry Follett would, for a price, undertake what needed to be done.

The priest abruptly palmed the miniature, and the conversation moved on to the details of Follett’s responsibility, payment, and duty.

When the terms were accepted, the black priest described the abnormal and difficult qualities of Follett’s “cargo,” especially the feeding instructions.

“The Blessed Oracle has little attachment to this world. Its withered limbs make it incapable of survival without close support. You must appoint a man to watch it night and day and to supervise its cleaning. It eats little, but its sustenance is specific: it eats only the marrow of bones, and those bones must be treated, prepared, by the speech of sinners.”

The other two priests paid great attention to Follett, gauging and weighing the confusion and disgust in his eyes.

“Your choice of the right men to join you in this mission will be crucial. They must have committed heinous crimes, and they must have memories of those deeds that they are willing to confess. You will encourage or force them to speak those confessions directly into the box of bones; the bone marrow will absorb the essence of their words. This ritual is called a Steeping, and it is at the core of your duties. The marrow will then be fed to the Blessed Oracle in the manner of an infant’s repast. Do I make myself clear?”

Follett nodded.

“Once the Oracle becomes accustomed to you, and when it needs to, it will speak.”

“Secretly? Just to me?” asked Follett.

“No, out loud. It has nothing to do with conspiracy or secrecy. The Oracle speaks only the truth. Much of what it says will make no sense to you because it often speaks out of time, giving the answer long before the question is asked or even considered. Its words should be carefully examined, especially if it is guiding you through unknown lands.”

A long silence filled the room.

“Do you have any questions for us?” asked the eldest priest.

Follett had only one question.

“What animal should be used for the preferred bones?”

A wave of unease elbowed aside the earlier composure.

“Preferred is a little difficult,” answered the black priest.

“You mean anything we can get on our journey?”

“Yes. Well, in part.”

“Part?”

“We cannot tell you what you already know in your heart.”

“Man bones?”

“We cannot say.”

“Human bones?”

Follett grinned to himself while maintaining a countenance of grim, shocked consideration. After allowing them to dangle from his hook, he changed the subject back to how the Oracle would bless and guide his journey and how he should speak to it. Thus, he indicated to his new masters that they had selected the right man to provide safe passage for the precious cargo. They gave him brief, broad answers and finished the interview with the pious conviction that their part in this transaction had been satisfactorily concluded. All other details were left to him. He had carte blanche in the “sacred” assignment.

Follett needed men who would obey without question, who had stomachs of iron and souls of leather. Men who would take a life on command and give their last breath for him and, on this particular mission, have no terror of the unknown or veneration of the abnormal. They would also have to have committed violent crimes that, if proven, would consign them to the pyre and the pit. The first two of his chosen company he had worked with before; the other five were strangers recommended to him.

Alvarez was his oldest acquaintance; they had nearly died together on four occasions. Without doubt, Alvarez would be the chosen guardian and servant of their precious cargo. Follett demanded that Alvarez accompany him to take charge of the delicate creature.

The Oracle had traveled from Brocken in the Harz Mountains. Alvarez and Follett were to collect it from a forest crossroads three miles from a tavern in the Oker region, a sullen valley dominated by the vast mountain range. On the third day, it arrived, escorted by two silent, heavily armed women and a tiny, birdlike priest. The soldiers placed the handmade crate, lined with chamois leather and silk, between them, and the priest again explained the complexities of the Oracle’s needs—the details of its feeding, travel, and preternatural appetites. He delivered his instructions three times in an eerie high-pitched singsong so that the tones, rhythms, and resonances insinuated themselves into the deepest folds of the men’s memories. Every particle of instruction, every nuance of requirement lodged there, keeping their disgust at what they had been told to do from ever touching them. They were simply caring for a rare thing that would direct them on their journey.

Alvarez took his charge seriously. He would protect and mother this abnormality, even against the other men in Follett’s chosen pack, if necessary. He was able to dredge up a kind of respect for the contents of the box, which helped dissipate his rising gorge every time he undid the catches and lifted the lid.

Pearlbinder was a bounty hunter and paid assassin, if the price was high enough. He was the biggest man in the pack, and the long riding coat he wore over his tanned fringed jacket suggested a bulk that resembled a bear. His speed, lightness of foot, and untrimmed beard added to the impression. He also owned the most weapons, including a Persian rifle that had belonged to his father. He carried many memories of his homeland and wore his mixed blood loudly and with unchallengeable pride, but his use of weapons was more an act of pleasure than an application of skill. Follett had known Pearlbinder for fifteen years and always tried to recruit him for the more hazardous expeditions.

Tarrant had the concealed ferocity of a badger entwined with a righteous determination, qualities that might be invaluable in this mission. He also spoke frequently of a family that he must get back to, so the payment at the end of this expedition would see his future solved. Thus, Follett would never have to lay eyes on him again—a conclusion that he relished with most men.

The Irishman O’Reilly was a renegade, wanted by the authorities in at least three countries. He was a ruthless man who needed isolation and a quick reward. In Ireland, he had been part of a marauding criminal family, most of whom found their way to the gallows before the age of thirty. He had been on the run all his life, and his slippery footfall had separated him from reality. Brave and foolish men might say it had turned him a bit softheaded, but they never said it to his face. Some of his stories seemed fanciful, especially when he spoke of times that were different from the ones they were all living in now.

Then there was Nickels, the bastard of one of Follett’s dead friends. He was fast, strong, and ambitious for all the wrong things. Skinny and serpentine, with a quick mouth and an even quicker knife hand, he was also the youngest, so they called him “the Kid.”

Follett knew he needed men experienced with the terrain, and the Calca brothers were perfect. They had grown up as mountain men and had traveled these lands before. Although they looked like twins, Abna was two years older than his brother, Owen. They were not identical, but they had learned to be alike, to think and act as one in defense against their brutal father and against the harshness of the nature that had no respect or interest in singularity. They were strongest by putting aside the need for any traces of individuality, opinions, or desires. They were bland, incomprehensible, and solid, the perfect slaves for Follett, who told them what to do and what to think. The Calcas obeyed him without question and mostly remained mute, except for a weird sibilant whisper that occasionally passed between them and sounded like a rabid deer dancing in a husk-filled field.

Lastly, there had been Scriven, who proved to be a grievous mistake. He had come highly recommended for his skill as a tracker and a bowman. Follett had taken him without suspecting that he was an avid practitioner of the worst form of blasphemy that the old warrior could image, and one that he would never tolerate in his company. But nobody saw Scriven’s demise coming, especially the man himself. Better that such errors are exposed early before they turn inward and slyly contaminate the pack. Scriven had been found spying on the other men and making written copies of their confessional Steepings. He had been caught listening and scribing Follett’s own gnarled words. Pearlbinder grabbed him and held him against a tree by his long hair. He pushed his sharp knife against the man’s jugular vein, allowing just enough space for his larynx to work and for him to attempt to talk his way out of his fate. He was midway through when Follett unsheathed his lance and pushed three feet of it through Scriven’s abdomen. Written words had condemned Follett before. Words written by others that he could not read. Ink keys that had locked him in a Spanish cell for three years. He had always distrusted written words, and now he despised them.

“Get it warm,” shouted Follett. Alvarez started to unpeel the stiffening bedding and clear the Oracle’s nose and mouth of frosted water. Dry blankets were unpacked from the mules and quickly bound around the small blue body.

“Choir,” bellowed Follett, and all of the men except Pearlbinder made a tight scrum around the diminutive bundle, forcing the little body heat they had toward their shivering cargo. This was the part they all hated, except Tarrant, who was always first to press close to the Oracle. Proximity to the otherworldly thing made the rest of the men ill and turned what was left of their souls inward and septic. But they had all agreed to be part of the ritual. It was in their contract. The balance of gold to horror was a much gentler bargain than many of them had made before. Their heat and guilt were needed, and they were balanced by the bliss emanating from the Oracle.

“I now know it lives. It only lives when it speaks or makes that sound of words,” said the Kid. “Behold, the rest of the time, it is dead.”

“Verily, it is not dead,” said Pearlbinder from the other side of the men. “Make no mistake, it sees and understands more of this world than thee ever will.”

The Kid’s smirking sneer was instantly quelled by Pearlbinder’s next words.

“It sees all and knows the ins and outs of thy soul. It remembers every stain of thy thinking and watches every act we commit. It will engrave a map of thy rotten heart on a scroll of its own flesh.”

Any talk of scrolls or books made the men alert and anxious. All knew such talk was impossible after what had just happened, but Pearlbinder was clever and could speak around things that no other dare even think.

“Take great note of what thee speaks, for it is remembering.”

The Kid spat, and nobody spoke again.

There was a gnawing silence as their breath plumed in the air, and each thought back on the words about animals and men and men who were animals. Something about the obscure statement that the Oracle had said seemed familiar and kept the bile of that day’s events at bay.

The landscape and the clouding-over sky had begun to close around them. Snow had left the growing wind and ice slivered into its place.

“Move out,” shouted Follett. “Tie Scriven’s horse on behind. We have four hours before dark.”

Everything was packed away, and the men were in their saddles and moving. Their leader stayed behind, mounted beneath the tree. When they were out of sight, he lifted his twelve-foot lance and pushed it high above his head and to one side so that its blade nestled and writhed among the ropes that held the frozen man to the swaying wood. The wolves would feed that night, a good time after he, and those he trusted, had passed beyond this place.

From HOLLOW by B. Catling, to be published by Vintage Books on June 1, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Brian Catling.