A series of interviews between a young, clean-cut journalist and an alternative, independent pichal pairi turns into an unexpected romance. But their relationship is tested when the entire world around them shuts down.

I met the pichal pairi by the Ravi’s bank at the mouth of a secret tunnel. She was sitting on rocks, massaging her backwards feet on pebbles from the riverbed.

“My mother always said,” she sighed, “this is good for plantar fasciitis.”

She was smaller than I’d expected, five-three perhaps. Pretty, with green eyes and walnut hair with copper and gold hues, so a red ripple went through it every time she shook her head. She wore ripped jeans, a white T-shirt with WHAT WILL PEOPLE SAY? printed on it in electric blue with a middle finger skewering PEOPLE, and an orange dopatta around her neck. No jacket, though the riverbank was chilly from late February winds. Woke, but somehow vintage at the same time.

“I didn’t realize witches got plantar fasciitis,” I said.

“I didn’t realize I’d be stuck with an idiot who wouldn’t know the difference between a witch and a churail.” She arched her back, stretched, and straightened. She spoke perfect English, slipping in and out of the language like an eel. “So, who’re you with again?”

“Dawn Magazines.”

“Ah, that bastion of anti-establishment sentiment. Nice.” She produced a cigarette from a shoulder bag on the rock beside her and lit up with a Zippo. The smoke drifted across the bank toward a buffalo wallowing in a stream that was once a river.

Buy the Book

#Spring Love, #Pichal Pairi

Everyone knows there are tunnels that go from the Fort to the Ravi and under the river—so the old guide at Lahore Fort told me when I visited years ago. Basements from Emperor Akbar’s time—many levels deep to the famous Fairy Palace—toss labyrinthine limbs toward the water. Not only did they give embankment against the mighty Ravi of the sixteenth century, they provided escape from scalding heat and quick access to the ferries should the Mughals face siege from enemy forces.

Now the Mughals were gone, the Ravi a muddy gash in the face of Punjab, its water a urine-colored trickle, and the tunnels—

Everyone knows the tunnels are a myth, they said when I first began asking around. Of course, no prince ever ran blind in that darkness, spilling gold coins and diamonds in his haste to flee the city. No queen, courtier, or guard made use of such secret passageways. And even if such tunnels existed, most certainly no pichal pairi with banshee wails and malformed feet haunted them. Was I ready to buy Badshahi Mosque next too? They’d heard it was up for sale.

Ghostly circles grew like mouths widening around me.

“Raza, right?” the pichal pairi said and blew another smoke ring at me.

“Yeah. I’m sorry about calling you a witch earlier. My bad.”

“Sure. Try not to stick around after dusk.”

Ignoring the alarming quip, I lowered myself next to her, aware of the proximity of her alien limbs curling and pressing against a litter of pebbles, first one mud-streaked foot then the other. Did she walk along the river between scatters of tents and tin-sheds, where hundreds of homeless families lived? After exiting Ring Road I’d noticed sickly-looking panhandlers—adults and children in rags tapping on car windows, slum-dwellers. I had no idea how long they had lived here. Generations? I made a mental note of looking into that for a possible piece.

She was smiling, a hint of teeth between lightly painted lips. I grabbed my recorder, clicked it on.

“Hello! Raza Minhas of Dawn Magazines here,” I began, “and I’m here with Lahore’s very own pichal pairi—Ms. Firoza of Old Ravi. Ms. Firoza, I’m very pleased to meet you.”

“Name’s Farah. Charmed, I’m sure.”

“Could you tell me a little about yourself?”

“And risk being doxxed? No, thanks.”

“A little about your family then. Are you married?”

“Your questions are boring.” She flicked ash between the pebbles. “Indubitably, delightfully unmarried.”

“Parents?”

“Ailing in a retirement home. No, we won’t be discussing details.”

“Any siblings?”

“I have a sister. She is very pretty.”

“What does she do?”

“I’ve changed my mind. Can you turn that thing off?”

“You’re kidding?”

“About not putting my personal info on record? I’m sure as fuck not.”

“Potty-mouth,” I said under my breath.

“Did…did you just use a kindergarten slur to tone-police me?”

I turned the recorder off. “No, Ms. Firoza, I didn’t.”

“Farah. Yes, you did.”

“So that’s it for the interview?”

“I said I’d meet you, then decide.” She lifted an eyebrow. “So, yes.”

We regarded each other. I looked away, then at her. Green eyes with flecks of hazel.

She licked her lips. “Are you hungry?” she said. “I’m hungry.” I must have looked worried, for she said, “For some chicken, moron.”

Which is how the pichal pairi and I went to eat Shahi Murgh Chanay at Lakshmi.

She had lived in Lahore for more than three decades. Her father was Parsi; his ancestors moved from Eastern Iran to Afghanistan a century or so ago. Mother’s family were nomads, descended from a Hindukush tribe called Abarimon.

Mentioned in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, these swift and savage mountain people lived alongside animals amidst tall pines and firs on the highest peaks and couldn’t be captured due to their tremendous speed. When Alexander of Macedon passed through a Scythian valley, his troops spotted an Abarimon male and gave chase. The back-footed man vanished quickly into the rocks and verdure, but later there were screams in the night and steel and animal noises. When dawn came, an entire regiment of soldiers was gone, the snow-whitened ground spotted with blood, littered with chewed up human feet.

Mortified and enraged, Alexander gave orders to track the aggressors with dogs and seasoned foresters. After three days and nights, they captured an Abarimon juvenile. She was hoisted on a pole like a hog, brought to the camp, and presented to the king. Alexander tried to touch her, but the Abarimon bared her teeth. The king laughed and ordered her caged so he could take her with him to the Indian plains. The moment the army left the valley, however, the Abrarimon gasped and fell to the ground, dead.

Alexander’s land surveyor Baiton would conclude that the Abarimon could only breathe their own valley’s air. The outside was poison to them.

“Baiton, of course, was blowing smoke up his own ass,” Farah said. “The kid was likely ill and the account exaggerated. It had nothing to do with the air. Our ancestors were nomads, for heaven’s sake.”

She had a point—further demonstrated by her presence in Lahore.

Springtime in the City of Gardens. A cool breeze patting the heads of white roses, honeysuckle, and gardenias set in a neat row by the house opposite the coffee shop. Our second meeting scheduled at Gloria Jean’s, and we were getting more comfortable.

Her name was Firoza, but she preferred Farah.

“I was Ferozeh at birth, but it was too Parsi a name and my father didn’t want anything to do with Iran or Afghanistan anymore.” She sipped honeyed green tea. “So my parents changed it when we moved to Pakistan in the seventies. I was ten.” She raised an eyebrow. “What?”

“I didn’t say anything.”

“You gave me a look.”

“Well, you don’t look fifty.”

“Appearances. Deceiving. And all that.” She dusted crumbs off her shirt. She had been dipping biscuits in her green tea, which I thought was weird. “Besides, I am half-Afghani, half-Abarimon. Deathless mountains,” she pronounced, “are in my bone marrow. Unlike you plain-crawling Lahoris.” She laughed not unkindly.

I was tempted to point out her current habitat of choice, but refrained. “So you’re a refugee?”

“When the Soviets invaded, my father knew the differently abled would be the first to get targeted. With us there was no question of staying when war came.”

I decided to move away from the morbid.

“What else do you like besides Peanut Pik, murgh chanay, and green tea?”

“Are we keeping an inventory? Chill the fuck out, bruh.” She wiggled her backwards toes out of her dainty buttercup flip-flops, retrieved Vaseline from her purse, and rubbed it on her heels. “God, that feels good.”

I watched her spread more lubricant over blisters. “Must be tough walking with a shifted center of gravity.”

She made a noncommittal noise.

“Did you go to school in Lahore?”

“LGS, then a few years at NCA and a summer at Boston U. My mother used to say education by dint of broadening your horizons, by showing you the world, can ruin you. Especially a pichal pairi.” The side of her mouth twitched. “I didn’t understand it at the time. I do now.”

“I’m not sure I follow.”

“Don’t worry about it.” She called to a waiter who came over, carefully keeping his gaze away from her feet. “Can we get the check please?”

“Jee, madam. Should I pack anything?”

“Just a slice of chocolate cake. The hazelnut, please.”

He moved off.

“Do you need a lift?” I said as we stepped out.

She shook her head. “Careem zindabad. Long live ride-share.” She held my gaze. “As before, I’d appreciate it if the piece you’re working on—”

“Alternate lifestyles and minorities in Lahore.”

“—doesn’t mention my family history or details of my personal life. No identifiers.”

“Nothing specific. No addresses or family names. I’ll keep my word.”

“And if you don’t,” she said, flashing teeth. “I know where to find you.”

“I have your number. Will get in touch if I have more questions.”

“Your questions are getting better and you’re a good listener. Rare, that.” She walked to the curb, where her Careem was waiting, the swing of her body throwing her spine up and back, turning her gait lord-like. She cast a coy glance over her shoulder. “I’m on Tinder too, you know. Just saying.”

I couldn’t help a grin. “Full body pic?”

“Don’t be an asshole.” She got into her car. “See ya, news guy.”

She likes chocolate, I thought. I’ll remember that.

We went to see Nighat Chaodhry at The Colony on Queens Road.

I’d like to think it was my irresistible charm that made Farah call me, but I’d be lying. Her Careem app wasn’t working and she needed the ride.

“I’ve only seen her on YouTube. The woman is a fucking genius,” Farah said as we settled on pillows the organizers had arranged on the floor. The hall was filled with college students and student-adjacent adults. They sat cross-legged, cellphones flashing in their hands. Someone opened the balcony door and pot smoke drifted in.

“Didn’t Plaza Cinema use to be here—” I began to say, but Farah put a finger to my lips. The lights were dimming. A yellow square lit up the stage. A wave of shushing went across the room as Shafqat Amanat Ali’s “Ya Ali” began to play. Wearing anklets and a solemn black-red lehnga Nighat Chaodhry appeared on stage from the left. She held red roses in her outstretched hands, an offering to the song’s eponymous patron saint Ali. Facing the audience, head bowed, Nighat placed the roses in the middle of the stage, swayed, and began to whirl. Her dance ebbed and flowed, her arms and legs transforming the music into geometric shapes of grief and hope.

She came empty-handed to Ali, the song told the audience, hoping her barren bowl of desire would be filled by the time she left his holy presence.

Farah watched the kathak performance with a glint in her eyes. Her right foot tapped the hardwood floor in tune with the tinkling of Nighat’s anklets and the subsequent lamentations of tabla, flute, and sitar.

After it was over and another dancer replaced Nighat, Farah rose and went to the balcony. Slipping my jacket on, I followed. Above us a pale February half-moon hung in the sky like a prop.

Farah lit a cigarette. She was wearing an orange kurta and a pleated pink skirt that fell to her calves. In the moonlight her feet gleamed like marble, and I wondered briefly what it would feel like to put my lips around her toes and suck.

I put my hands on the edge of the balcony.

“So, what did you think?” I said.

She inhaled and blew smoke out her nostrils. “Woman’s a genius.” She looked at Queens Road brimming with evening traffic. “When I was young I used to wonder why people danced. What compels our body to harmonize with music? Why waste all that energy?”

“The taal of the tabla, the beat of the drum. The obvious answer is dance is like sex,” I said. “And sex is life.”

“You’re such a guy.”

“What’s your hot take?”

“You know all that time she was dancing, I kept thinking of Anarkali.”

“The dancing girl?”

Farah twisted her wrist and pointed her fingers at the sky. Simultaneously she stepped forward with a foot, her body in line with her arm—a classic kathak step; but her balance was off. Even I could see that. “Yes.”

I knew the story, of course. “Why?”

Smoke ribboned to the sky from her airborne hand. She breathed and straightened. “You remember in the story Anarkali and Emperor Akbar’s son Saleem fall in love?”

“Yes?”

“When Akbar finds out, he is livid, right? How can his son, the future emperor of India, fall in love with a dancing girl! In his rage Akbar has the girl entombed alive. Bricked up airtight. Left to starve to death while the prince goes on to wed his queen and retain royal rights to fuck concubines on the side. A tragic ending, eh? Patriarchy wins again.

“Except there are other versions of the story.” She took another drag and offered me the cigarette. I took it. “In my favorite, a mason is bought off by the prince and he lets a brick sit loose so the girl can breathe—while the prince’s men burrow beneath the walls a couple nights later and get her out. Anarkali is taken to the tunnels beneath the Ravi and whisked off to Delhi, where she lives happily ever after.”

I had a vague memory of reading this particular account years ago.

“Escape.” Farah’s eyes shone. “The dancing girl escapes, Raza. They can’t have her, after all. All of dance, for me, is Anarkali’s escape. A flight of mind, body, and spirit.” She smiled and held out her hand for the cigarette.

The balcony door opened. Music drifted out. A contemporary number. The Dunhill Light was moist from Farah’s lips. I dragged on it, gave it to her, leaned in, and kissed her cheek.

When I pulled back, she was watching me, her green-blue eyes trained on mine.

“What was that?”

I shrugged, but my heartbeat had picked up.

“Next time, ask first.” Farah puffed, then flicked the cigarette stub off the balcony. It spun all the way down, scattering embers into the night. She pulled out a Ferrero Rocher, popped it into her mouth, and munched.

She turned to me. “May I?” she said quietly, caught the V of my shirt, and pulled me toward her. It was a firm, inquisitive kiss. Her breath was hot and tasted like smoke, chocolate, and metal—it made me shiver. I took her face in one hand, ran my fingers through her hair. She smelled like lavender and the barest hint of sandalwood sherbet. She gently bit my upper lip and sucked it, before drawing back to examine me.

“Well,” she said.

“I never said yes,” I told her. A couple stood half a dozen feet away, pretending not to look at us. The girl laughed. I felt tremulous and very aware of our surroundings.

“Fair enough.” Farah slipped her hand into mine. Her fingers were cold and so soft. “You can be mad at me in the cab.”

We went to my place.

You don’t need to know the details, except this. A pichal pairi’s feet curl with pleasure. When they do they tend to turn forward.

It is fascinating, watching them rearrange. Pleasure, or happiness, it seems, is their true north.

Farah had published poetry under a pseudonym. Quite decent, too. Spring rain drummed on my patio the following Sunday as, bare-chested, I fetched my acoustic and played a few progressions to render her words into song. She lay on her stomach on my Beatles floor rug listening, her legs penduluming in the air. She was wearing my Freddie Mercury shirt and nothing else.

“Not bad,” she said, eyes closed, “although one can tell the lines weren’t written for music.”

“Neither was Faiz’s work, but look at what folks did with that.”

“Eh.” She turned her head the other way, blew a copper-hued hair strand out of her eyes. “I’d like to check out Hast-o-Neest sometime.”

“The traditional arts place?”

“Yes.”

“Sure.” I put away the guitar and dropped to all fours. I began kissing the inside of her thighs. Her limbs had a fine down that was exquisitely erotic. “I was wondering why someone with a degree in the arts doesn’t seem interested in pursuing them as a career.”

Farah made a noise. She rose on her forearms and arched her back, allowing me access. “Who said I’m not interested?”

“Hmm.”

A matter of some urgency then engaged our interest—multiple times—until night came and took Farah with it.

Despite my seductions, despite my pleas, my pichal pairi wouldn’t sleep over.

Were you ever bullied as a kid, Farah?

What do you think, genius?

I’m so sorry.

It’s okay.

Was it at school?

Yeah.

Did you get mad?

A little. On the first moonless night of my adolescent cycle I ate him.

Her favorite color was orange. Which, in retrospect, explained her choice of clothing.

She loved lychee in the summer, mixed nuts in the winter, and Aamir Khan in Rang De Basanti. She hated manspreading, mansplaining, and the Jonas Brothers. Loved the smell of fresh roti, the first bite of mango in season, and Hot Spot, where she once spent hours snapping pictures of the desi posters. She hated dahi bhallay, bananas, and loudspeaker sermons on Friday. She thought Johnny & Jugnu was overrated (the burger patty is too chewy!) and, to my horror, couldn’t get enough of Salt’n Pepper’s club.

“This is why people break up,” I told her when she wouldn’t stop kissing me with her mouth full of that fucking sandwich.

She had a hell of a time with shoes. Her left foot was her right and her right foot left. Her Achilles tendon twisted like a vine to bring her hind foot to the fore. None of this was conducive to good shoe sizing and heels were out of the question. Ergo, mostly flip-flops.

She loved Breaking Bad and the fact that I hated Pakistani serial dramas.

“I can’t,” I begged. “Please. I just can’t.”

“But they’re so much fun. They’re so stupid their stupidity is addictive. Watch one with me, babe.” She batted her long witch eyelashes and pressed her boobs against me. “Please?”

I watched an episode of Mann Mayal and almost died. Seriously.

I don’t want to sound like a PTV soap opera, I told her, but my parents died when I was nine. I have no siblings. A somewhat negligent aunt raised me. I moved out at seventeen and have cruised along pretty much on my own since. My parents left me some money and a house in Model Town. It was enough to get me through college, enough to get somewhat settled.

No, I don’t see my aunt much. A phone call every Eid or so. My relatives on my mother’s side aren’t any more interesting. Every six months I get the urge to hang out with cousins. Usually takes one cards night to remind me how much they bore me.

Do I feel like I had a lonely childhood? Not at all. I had neighborhood kids to play cricket with and a stray cat named Mankoo, whom I adopted. Oh, I don’t know—the chowkidar named him, I think. Yeah, I know it’s a dumb name, a monkey’s name.

I loved that cat, though. He refused milk from any hand but mine.

Farah vanished for a week. My phone calls and texts went unanswered. I went to the Ravi. Where the mouth of the tunnel should have been was a boulder. Moss grew on it. I couldn’t find a way in. No, I won’t describe its whereabouts. She said not to.

I thought about filing a police F.I.R., but changed my mind. I went to all her favorite joints to ask if anyone had seen her. They hadn’t. Just when I was frantic enough to reconsider seeking help from the cops, my doorbell rang. There she was, barefoot, in ripped jeans and an orange SAVE OUR PLANET T-shirt. Smiling, a bit pale, but fine.

We clung to each other, kissed, and made love, but I could not get anything out of her. Next time she’d try to let me know, she said, but sometimes she just had to go away.

I had to be content with that.

How does it feel, Farah?

How does what feel?

To live a life with your feet pointing the wrong way all the time.

Who says my feet point the wrong way? Maybe they’re fine and it’s my torso that never got the message. Maybe it’s my head that’s backward.

Maybe I’ve just been looking over my shoulders all my life.

What woman, she said, hasn’t spent her life compelled to look at the past, the baggage car of trauma that follows her—even as her feet march her forward?

We went to the Aurat March in Lahore.

I was assigned to cover it for Images. Farah had been planning for months. She wore beads and a hand-painted yellow kurta with the words YOU FEAR LOVEMAKING BUT NOT WAR-MONGERING? in front and PICHAL PAIRIS ARE WOMEN TOO on the back. In her hands she held a placard: LOOK AT THIS POSTER, NOT AT MY FEET.

Surrounded by hundreds of people, we marched down Egerton Road, chanting My body! My choice! My body! My Choice!

An eighty-year-old lady in a wheelchair proclaimed I HAVE WAITED A LIFETIME FOR THIS MARCH. A trans woman in a bright-red dopatta drummed a dholki hung around her neck. The woman next to her hoisted a sign that said STOP TRANSGENDER RAPE. Women of all ages and sizes stormed down the street. Men too. So many “uncles.” Next to a young woman a gent in his sixties held a placard that read MY DAUGHTER, HER CHOICE. A mustached banker-type smiled at Farah as he walked along, holding a ten-year-old’s hand. The kid was hopping along in excitement. Her poster said DISTRIBUTE MITHAI. IT’S A GIRL!

Farah grinned at her and the girl beamed.

A tall sharp-featured girl wearing face paint and a pearl necklace bumped into Farah.

“Excuse me,” she said, then her gaze dropped to Farah’s feet. “Oh.”

“No prob at all.” Farah smiled. “March is packed. Which is great.”

“Uh huh.” The girl inched away and in a low voice spoke to her companion, a heavy-set woman with silver hair. They looked us up and down.

“Everything okay?” Farah said.

The woman pointed at me. “He shouldn’t be here.”

“He’s covering the march for a newspaper. He’s an ally.”

“This is our day,” said the tall girl. “Would be nice to have one fucking day without men.”

“Excuse me?”

“You shouldn’t be here either,” said the girl.

Farah’s smile widened, but it didn’t reach her eyes. “You want to be careful now, sister.”

“Oh, sweetie.” The girl smiled brightly. “I’m not your sister.”

“That’s enough, Hira.” The woman nudged the girl. “They’re not worth it.”

They moved away and disappeared in the crowd.

Farah’s face was flushed. “Fucking pichal pairi haters.”

“I’m sorry.” I squeezed her hand. “Every party has a pooper, I guess.”

She adjusted her baggy jeans to better cover her feet, but not before I caught a glint of long, sharp claws protruding from her toes. She raised her placard higher. “Let’s go.”

We finished the march as planned.

That night we heard about the incident at the Islamabad Aurat March. A bunch of mullahs had crashed it, pelted stones at the marchers, given a teenage boy a concussion. The kid needed a CT scan and a couple nights in the hospital.

It left Farah furious. I couldn’t reach her for days.

a mile of twisted metal, a scorched train

(she wrote in a poem)

a train aflame

trails my love’s wedding dress;

flanked by men

she stumbles down the aisle.

Her favorite place in the whole wide world was not in Lahore.

Not in this urban village foaming with concrete and traffic and smog that made your eyes water. This over-developed parochial town with its incestuous elite who all knew and fucked each other and played golf in private clubs on acres of green, even as the last tracts of nature available to fruit-wallas and chanay-wallas shrank with every passing day.

Of necessity she loved Lahore, its potpourri of culture, cuisine, music, and literature. For remembrance of times past. But her favorite place in the world was not in Lahore.

My dear, have you ever beguiled and partaken of a wayfarer?

Huh?

Cannibalism, love. Pichal pairis are notorious for taking on the form of lovely women, luring men off lonely highways, and feasting on them.

You’re joking, right?

No, my butterfly. They say you hang upside down from trees—tree-spirits of a sort—and latch onto any unfortunate micturating under said foliage.

Rumors, you moron. Most of us prefer regular food and lodging. At least till someone pisses us off.

Oh.

Oh, indeed.

Do I…ever piss you off, Farah?

Yes, darling.

Uh. Okay.

But you shouldn’t worry. You taste awful.

Is that insult or reassurance—who can say?

I’m kidding. You taste sweet. Okay, sometimes a little salty, a bit gummy maybe, somewhat nasty, but that’s usually after you drink that stupid kalonji oil you like so much.

Gee, thanks.

If it’s any consolation, you taste sweeter than most men I’ve swal—

Not helpful, Farah!

*Laughter.

I had a work thing in Karachi. I asked Farah if she wanted to come. She surprised me with a yes.

We booked first class tickets in PIA. She paid the fare; I couldn’t have afforded it.

“Oh, chill, my dude.” She grinned at my discomfort. “It’s all good.”

Two days before the flight she brought a suitcase and emptied it in my living room. Skirts, jeans, shalwar kurtas, baggy pants, T-shirts, lots of undergarments, and flip-flops. I was assigned ironing, while she would make dinner and pack. A chappal whizzing by my head preempted my protests.

Farah flitted from room to room, bouncing with nervous energy. It drove me batty.

“Could you please settle down?” I slid the iron over her undies. “I’ll burn it if you keep dancing around me.”

“You’re right.” She dropped the hangers she was holding and threw herself on the couch. “I need a break.”

“Are you okay?”

She drummed her fingers on the armrest.

“What’s up?”

She moved uncomfortably. I turned off the iron and joined her on the couch.

“My sister lives in Karachi,” she said. “That’s one reason I wanted to go.”

“Hey, that’s great.” Farah didn’t talk much about her family. I’d assumed it was a pichal pairi thing. “We should totally meet up with her.”

“She’s very pretty. Runs her own business: a yoga studio and a garments store. She is doing very well.”

“Sounds wonderful.” I squeezed her hand. “But do I sense a ‘but’ coming?”

Farah shot me a glance and sighed. “It’s just…I live in a goddamn tunnel, Raza. Like a hobbit. She lives in a high rise near French Beach and wears branded clothes and sells branded shit. I haven’t seen her in years. Not since our parents—” Her voice lifted and fell. “I don’t even know how to talk to her anymore, and…now I’m planning to fly off with you to see her.”

I pressed her thigh. “You don’t have to see her, you know.”

“I guess.”

“Sleep on it. Meanwhile, think of walks on the beach, prawn haandi at Boat Basin, nihari at Burns Road—and let’s pack our shit.” I rose to my feet and kissed the top of her head.

She responded by grabbing my crotch.

“Watch it!”

“Or what?”

Like a bull held by its horn I was led into the bedroom, where she did naughty things to me, wearing only socks.

It was the last time the pichal pairi and I made love before the world was cancelled.

We were on our way to Allama Iqbal International when the news broke.

I called the airline but found a busy number. I dialed airport help. An impatient voice told me all PIA flights had been canceled.

“What on earth is happening?”

“It was on one of the flights, sir. A passenger from Tehran.”

“So they cancel other flights as well?”

“Sir, all non-emergent flights to Karachi have been canceled.”

For several weeks we’d heard rumors of a disease that had emerged in a neighboring country. The few cases reported in Sind hadn’t really raised eyebrows since they were all returnees from abroad and had been house-locked immediately.

We thought we had plenty of time. Until we didn’t.

I called a well-informed friend at the paper. Reliable reports that the country would go into lockdown in less than forty-eight hours, said my buddy. And a good thing too. This was no ordinary illness.

Whatever it was, it was killing people like flies.

I asked Farah to go into house-lock with me. She said no.

“There are hundreds of homeless people who live around Ravi. That’s my neighborhood. They’re going to starve when the rich shut themselves in their mansions. I have resources. I can help them. But I can’t do that and return to you. I’ll bring that damn bug with me.”

“I’ll take the chance.”

“I won’t.”

“We don’t even know it will affect you the same way. You’re…”

“What?”

“You’re different.”

She shrugged. “Good. It means I have a better chance of not contracting and dying from the fucker.”

“But what if you’re affected worse than regular people? Listen, Farah,” I said, not liking the desperation in my voice. “I’m not letting you go out there alone.”

“That isn’t your decision.” She picked up her suitcase and turned to go.

I resisted the urge to grab her wrist. Instead, I followed her outside. “What if we both stayed here and took occasional trips to wherever you need to go and dropped ration packs there, or something?”

Her hair flew in her face when she shook her head. “I’ll be going out to help every dayIt’s simply too much of a risk for you.”

“Holy shit, are you listening to yourself? You’re not a health worker. You’re not Mother Teresa. It’s not your responsibility.”

The murky green-blue of her eyes burned. “Let me be very clear, Raza. I could vanish so quickly you’d never even see me go. But I wanted to talk. I wanted to make sure you understood. Who knows how long this will—”

“That is my point, Farah. We don’t know how long—”

“—last. So”—she took a deep breath and let it go—“I don’t want to see you for a while.”

“What?”

“I don’t want to see you. And I don’t want you to come looking for me. Is that clear?”

I stared at her. “Why does that sound like a break up?”

“Because—” She stood on tiptoe and, placing one hand on my unshaved face, kissed me hard on the lips. Her breath was warm, and her skin cold. “—it is. For now. Take care, Raza.”

With that Farah swiveled on her backwards heels and strode away on a rapidly emptying street.

Lahore retreated into house-lock to wait out the mystery illness.

Rangers were stationed at strategic places all over the city. All businesses except food and medical stores were shut down. To get from my place in Model Town to the news office near Pepsi required passage through two checkpoints. If you weren’t wearing a mask, you were berated. If there were children in the car, you were asked to pull over while the army man called in to see what should be done with you.

No children and a press card meant my life was easier than most’s.

I Skyped and physically interviewed doctors and healthcare workers. With a physician friend I co-wrote an article for EOS that got a fair amount of traction and landed my buddy a slot on Indus News.

From backdoor army channels I bought five thousand surgical masks and had them distributed in the kachi abaadi near Kainchi. Donning one myself, I went with a team of rangers to give out food and hand sanitizer to unemployed laborers sitting at roundabouts, waiting for the world to resume its dysfunctional working. These were the invisibles who were everywhere and nowhere. The worker atop the bamboo scaffold at your uncle’s plaza. The watchman at the house your father was building. The ditch digger who came once a week with your gardener. Society sweep. Raddi-wala. The woman who rifled through your trash, and her son who swept the steps for a tip. The sun-darkened, cachectic faces of True Lahore.

Victims of the house-lock numbered in the millions. Farah was right.

Three weeks in, and not a single message from her—even as my WhatsApp bulged with misinformation, memes, and magical cures for the illness. My calls went to a recording that apologized and informed me my desired number was currently turned off.

I told myself I never really made a promise. I went to the Ravi and the river was there. Overhead, the sky, an impeccable blue Lahore hadn’t seen in decades, simmered with brown cheel kites. They cried and swooped at chunks of sadqah meat commuters bought from roadside vendors and flung in the air to ward off evil from their loved ones. No dogs, though. Usually there were several packs around. Under the bridge homeless men huddled together without masks or shirts. They whispered when they saw me. I tightened the strings on my N95, got out of the car, and handed out money and ration packs. When they tried to swarm me, I shouted at them to back up six feet. They retreated.

I walked along the river till I found the hill and the tunnel mouth still blocked by the boulder. It was impossible to tell there had ever been an opening here.

Two teenage boys in shalwar kameez were tethering a goat in front of a makeshift tent. I beckoned them over. Showing each a thousand, I asked if they had seen a pichal pairi around. They looked at each other. The lanky one with a farmer turban on his head scratched his chin.

“Don’t know what you mean, sahib,” he said in Punjabi.

It took me a moment to realize they were protecting her. “Listen, I know Farah-bibi very well. I mean her no harm. I haven’t been able to reach her for a while. All I want”—I added another thousand-rupee note to each hand and held the money aloft—“is to make sure she’s okay.”

The boy with the turban elbowed his friend. The latter shrugged and reached for the money. “Farah-bibi’s probably fine, sahib,” he said through buckteeth. “I saw her a couple days ago.”

“Where?”

“All over, sahib. Munir the ferryman has been rowing her up and down the Ravi for weeks. Munir told my chacha that they’ve given out more ration bags than the government.”

I gave him a thousand, held the second note back. “Can you tell me where to find her?”

“Sure.” He gestured at the tunnel mouth behind me. “She lives in the tunnels. Everyone knows that.”

“Everyone?”

They snickered. “We’re river dwellers, sahib,” said the first boy. “We know the water’s secrets.”

“Know a way to get past this?” I nodded at the boulder.

The turbaned boy hesitated, glanced at his friend, and nodded.

I handed them the promised money, took out my wallet, and showed them its contents. “Take me to her and all this is yours.”

The second boy reached out. Firmly, he closed my hand around my wallet.

“Keep your baksheesh, sahib. If you’re her friend and here to help, we’ll show you the way. But we won’t go in.”

“Why not?”

“She may be the nicest pichal pairi that ever lived,” said the boy with buckteeth, “but she’s still a churail. And you enter a churail’s house at your own peril.”

I found the pichal pairi at the end of a secret tunnel. How I got there is none of your business.

Blanket pulled up to her neck, she lay on her side in a canopied bed in a room wallpapered with white and blue stripes. At the foot of the bed perched a bench piled high with frilled pillows. Dirty Dancing and Rang De Basanti posters hung above a couch covered in aqua fabric. A gold-framed Sadequain replica, softly lit by niche lights, swirled across one wall. Three bookcases lined the sidewalls with the collected works of Sylvia Plath and Parveen Shakir poking their heads out like stone animals.

The air was hot and smelled of camphor.

I went to her and whispered, “Farah.” She stirred. I reached out to touch her. “Farah, it’s me.”

She shivered and her head came up. Something was wrong with its shape. “Who’s there?” Then she made a sound, something between a gasp and a keening. “Raza?”

Quickly she thrust a hand to paw at the side table. I saw a flash of pink as of wrinkled pale drapes, and the lights went out. When they flickered on, Farah was sitting up, leaned against the headboard. Sleep hair seethed around her face. Her eyes were red and the eyeliner was a mess.

“You’re such a shit,” she whispered and tried a half-smile. “You broke your promise.”

“I made no promises.” I lowered myself next to her. She shifted to make room and the bedroom shifted with her. A sense of unreality came to me like heaviness in the head, and vanished.

“Where the fuck were you, Farah?” I said. “I was worried sick.”

“I was here, trying to—” She broke off with a cough that came from deep in her chest. It shook her entire body. Sweat beaded on her brows. She recovered, took a long breath, winced, and said, “I’ve been trying to help, but I guess I overdid it. I woke up real tired two days ago and”—she waved vaguely at the room—“I haven’t really been able to get out of bed since.”

I placed my hand on her forehead. She was burning up. I could smell her sickness. A humid, sweaty tang in her hair, her pores. The odor of a sick dog.

Her nose was running.

“You’re sick, Farah. This may be pneumonia. Hell, this may be that fucking bug. We need to get you out of here.”

“I’ll be fine, but you need to get away from me.” She wiped her forehead with a hand. “Please just go. I’ll come see you when I’m better.”

“Like fuck I will. You need fluids and medicine. Is there food here somewhere? A kitchen? Maybe some soup.”

“No, babe.” Farah laughed. There wasn’t any laughter in her eyes. “I’m all out.”

“Then let’s go to my place. Come on, I’ll help.”

She shook her head. “Ain’t happening, love. I’m too dizzy.”

“I’ll carry you if I need to.”

“No. It’ll take us a while to get out and I’m…I’m too weak to create—” She began to cough again.

My legs trembled when I got up. “Wait here. I’m gonna go get some things for you.” I looked around, as a shudder went through the bedroom. The film posters wavered as if the movies were about to play. The niche lights dimmed, then resurged.

“Farah,” I said. “What is this place? How’s there electricity here?”

She tried to get up, but her legs gave out. Like a leaf from a felled tree she sank into the covers. “Please, Raza,” she whispered, closing her eyes. “If you care about me, please go away and don’t come back.”

I was already running.

It was after maghrib when I got back. I had taken at least three wrong turns in the dark and two tumbles, resulting in a cut on my palm and a leak in the milk carton. It must have left a sticky trail for a mile.

Just when I feared I was lost I saw a flickering light. I hurried down the tunnel and stopped at the doorless entrance of her bedroom.

In a chamber of granite and limestone she lay on a bed of moss and leaves. Two oil lamps, one in each corner, showed chairs with broken legs, heaps of pink plastic bags (the sort vendors sold sadqah meat in), soda cans, broken pitchers, and clay pots. Gunnysacks filled with refuse. And bones strewn everywhere.

Gleaming vertebrae, dull scapulae, mandibles and maxillae, skulls with deep eyeholes, incisors, and canines. Leg bones. Thigh bones. A veritable kingdom of the picked clean.

Seized with horror, I lurched to her. “Farah.” When she didn’t respond I dropped the supplies and grabbed her shoulder. “Farah, please.”

The netted mass that was my girlfriend’s shape crumpled at my touch. Wet grass rustled, eggshells from river birds cracked, the anthill beneath the fishing net stirred. Its shiny black denizens poured out in waves, swarmed to the walls, and broke against them.

I didn’t scream. Did a part of me expect this?

I settled down: into the bone dust, the odor of incense and rain-washed leaves, the crackling of ant bodies under my boots, the stillness of the air. I steepled my fingers and rested my chin on them. The river whooshed somewhere above me, a distant echo, and an image came to me of a shadow-girl bolting in the dark. The tunnels, they go from Lahore Fort to the Ravi and under it—an old chowkidar told me when I visited Lahore Fort so many months ago. Crisscrossing, apple-saucing, elbowing the river before turning southeast. Nearly five hundred kilometers they ran so the Mughal princes and their courtesans could elope, escape, abscond—all the way to Delhi, where they would live happily ever after. Why shouldn’t the tunnels run thus for a girl in a white T-shirt, an orange scarf, and blue jeans fleeing death, disease, and countless versions of herself?

This cavern should stink, I said to myself as I rocked back and forth on my perfectly formed heels. All that filth and refuse.

But the cavern smelled of cedar and pine.

Seated in the chamber at the end of the tunnel—no, I won’t tell you which one—I tore open the soup packet and ate my fill. I licked my fingers and the hole in the milk carton, and drank the remaining (thimbleful of) milk. I munched all the chocolate, including the Ferrero Rocher.

After, I went home.

THE END

On the last day of April when the first of the heat waves reached Lahore a postcard dropped into my mailbox. This was surprising because our mailman had died two weeks prior from the contagion and the postal service had been temporarily shuttered.

Back inside, I took off my cloth mask and placed the card on the dinner table. Carefully I washed my hands with soap, dried them, returned to the table. Thoroughly, and avoiding the writing, I sanitized the postcard with alcohol. The picture was a seascape with a dancer in the foreground caught by the camera in the most fluid of transformations.

I held the card between my palms. I blinked a few times—my eyes were wet—and read the back. There it was, the stamp of the city it was mailed from.

In the middle of the card were three lines printed in neat handwriting. The ink smelled like mint and roses.

No, I cannot tell you what they said.

The postcard said not to.

Buy the Book

#Spring Love, #Pichal Pairi

“#Spring Love, #Pichal Pairi” copyright © 2021 by Usman T. Malik

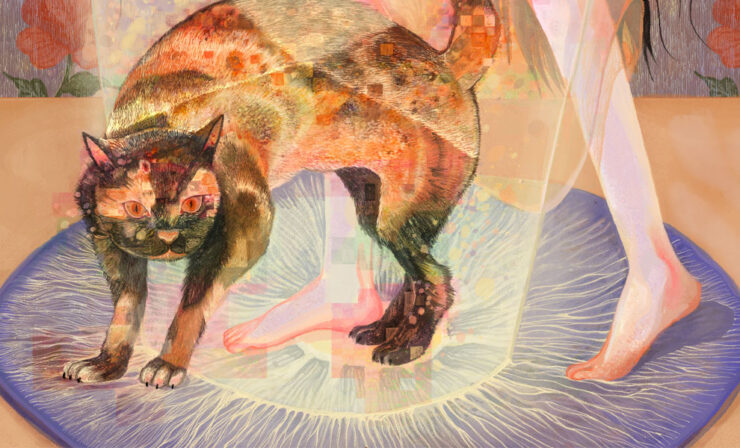

Art copyright © 2021 by Hazem Asif