Before we dive in this week, make sure to check out last week’s article by author Ferrett Steinmetz, who asks the question, “Is there such a thing as a necessary prequel?” Some great thoughts about prequels and, of course, focusing on The Magician’s Nephew as an example of a prequel that gets it right!

In 1958, C.S. Lewis recorded a series of radio interviews about love. These would go on to become the basis of his 1960 book, The Four Loves. The Narnia series were all in print by this time, so I’m not going to pretend here that The Four Loves was in any way in the back of Lewis’s mind as he wrote The Magician’s Nephew. However, what is clear is that The Magician’s Nephew is also intended as a sort of “tour” through the world of love as well. It’s not surprising that some of Lewis’s core insights and thoughts about love exist in both books (in fact, as we’ll see when we get to Perelandra and again in ‘Til We Have Faces, some of these themes are touchstones he returns to over and over again in his work).

So, I thought it would be interesting to use Lewis’s later thoughts as a framework to explore what he’s up to in this one. Being Lewis, of course he’s going to use ancient Greek concepts of love as the basis for his philosophical experiments…

First, we have “Affection” and the Greek word στοργή (storge).

Affection, Lewis tells us, is seen most clearly in family. The affection of a parent for their child, or a child for their parent. It’s a love that we see in animals as well as people, a “humble love” Lewis tells us…and where people might brag about friendship or romance, they may be ashamed of affection. He uses the example of a dog or a cat with its puppies or kittens as a favored picture of affection: “all in a squeaking, nuzzling heap together; purrings, lickings, baby-talk, milk, warmth, the smell of young life.”

Of course, for Digory, his mother is a central figure throughout the book. He’s worried about her health. He’s trying to keep quiet so as not to disturb her rest. When his uncle insists that he send Digory through to another world, Digory’s first thought is, “What about Mother? Supposing she asks where I am?” When Jadis is brought back to their flat, his biggest concern is that she might frighten his mother to death. He’s focused on finding some healing for her, once he knows that might be an option, and when Jadis starts trying to use the idea of his Mother to get him to steal the fruit which he knows he must not, he asks her why she cares so much, all of a sudden, for his mother. He has “natural affection” for his mother—but why would Jadis? “Why are you so precious fond of my Mother all of a sudden? What’s it got to do with you? What’s your game?” And when she is finally healed, why, it’s all singing and playing games with Digory and his friend Polly.

Lewis tells us that affection is often—even commonly—mixed in with other loves, but it’s most clearly seen here, in the bond between a child and their parent. It’s the simple love that is, in many ways, the engine of this book. And where it is lacking—for instance, we should expect that Uncle Andrew should have this same affection for his own sister… though if he truly has any such affection, it has been marginalized by other things—it brings disastrous results.

Affection covers an array of loves. Like animals, the care of mother to babe is a picture of affection. It relies on the expected and the familiar. Lewis describes it as humble. “Affection almost slinks or seeps through our lives,” he says. “It lives with humble, un-dress, private things; soft slippers, old clothes, old jokes, the thump of a sleepy dog’s tail on the kitchen floor, the sound of a sewing-machine…” Affection can sit alongside other loves and often does. For example, when two adults fall in love it is often because of certain affections—a particular location, experience, personality, interest—that begin to wrap around the couple so to make love an expected and familiar part of their shared lives. It’s the familiarity of “the people with whom you are thrown together in the family, the college, the mess, the ship, the religious house,” says Lewis. The affection for the people always around us, in the normal day-to-day of life, is the majority of the love we experience, even if we don’t label it.

Then we go on to “Friendship” or φιλία (philia).

Lewis says friendship is “the least biological, organic, instinctive, gregarious and necessary…the least natural of loves.” He goes on to say that “the Ancients” saw it also as the “happiest and most fully human of all loves.” Why don’t we talk about it more in the modern world? Lewis thinks it’s because so very few of us truly experience it. You want to talk about affection or romance, and everyone perks up their ears.

Lewis says that “Friendship must be about something,” a common interest or goal or experience. That’s why people who “just want to make friends” find it difficult…you can’t build a friendship around wanting friendship, it needs to have something else in common. It can be philosophy or religion, or a fandom, or funny stories or, as Lewis says, “dominoes or white mice.” What matters is that you have something that you share.

Digory and Polly become friends practically by accident. The first sign of their friendship is, more or less, summed up by Polly’s question to him the first time they meet, and soon after Digory moves into his Uncle’s house: Is it true that his uncle is mad?

The mystery bonds them to one another at once, along with the reality that they are both home for the summer, neither is going to the sea, and so they see each other every day. Polly introduces Digory to her “cave” in the attic and eventually they go off on an “adventure” together through the attics of all the row houses and that’s how they find themselves in Uncle Andrew’s room and, much to their dismay, traveling into other worlds.

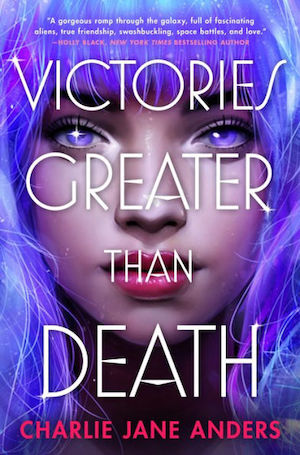

Buy the Book

Victories Greater Than Death

A scene I love in this book that captures their friendship well, is after Jadis is brought to life (Digory’s fault) and brought back with them to London (also Digory’s fault), at which point Polly says she’s going home. Digory asks her, you’re coming back though, right? He needs her with him. Polly says, rather coldly, that if he really wants her to come back he should apologize. Digory says he’s not sure what he has to apologize for and she points out several things: he acted like a “cowardly bully” and hurt her wrist when she was going to leave Jadis’s world and he didn’t want her to; he struck the bell and woke Jadis when Polly said not to; he turned back to Jadis when they were escaping into their world, although Polly didn’t want him to. Notice that in all three things, Digory is working against their friendship. He is forcing his interests, his decisions, on Polly. It’s the opposite of friendship, where their joint interests bring them together.

Digory is surprised when Polly lays it out. She’s right. He’s not been a good friend. He apologizes at once, and tells her again that he needs her, that he hopes she’ll come back. And Polly, when she forgives him, forgives him fully. Later, face to face with Aslan, Polly is asked if she’s “forgiven the Boy for the violence he did you in the hall of images in the desolate palace of accursed Charn?” Polly doesn’t hesitate for a moment, she just says, “Yes, Aslan, we’ve made it up.”

And, like many friends, their love for one another only grows as they gain more and more things in common. How could you not be friends with someone when you’ve ridden a winged horse together to the end of the world? Their love for Narnia and Aslan becomes a core part of their friendship and, as we’ll see in The Last Battle, they remain friends their entire life.

Lewis sticks to the Greek with the third kind of love, calling it simply Eros (ἔρως).

This is what we think of when we say someone is “in love.” Lewis doesn’t use the word “romance,” as that has a different meaning for him. This is also the least helpful section to use as a lens for The Magician’s Nephew, as his exploration of the idea is pretty thorough and nuanced in a way that The Magician’s Nephew of necessity is not. (Interesting sidenote: Lewis received a good amount of criticism for his frankness in discussing sex when he spoke about Eros on the radio.)

Much of what we see about Eros in The Magician’s Nephew is related to the power of desire. Old Uncle Andrew is suddenly and irrevocably attracted to—and terrified of—Jadis the moment he sees her. Yes, Digory had seen her as beautiful (Polly didn’t really see it), but Andrew falls into, as Lewis calls it, a sort of grown-up “silliness.” He forgot she had frightened him and started saying to himself, “A dem fine woman, sir, a dem fine woman. A superb creature.” And “the foolish old man was actually beginning to imagine the Witch would fall in love with him.”

Which, of course, she doesn’t, as Jadis is not one to dabble in any of the loves…she didn’t even show love to her own sister. It’s telling that this passion never really wanes on Andrew’s part, even after all he goes through in Narnia, and even when he is (sort of) reformed in his later years. He’s still talking about that “dem fine” lady in his retirement in the country.

Lewis spends a good amount of time in The Four Loves teasing out the ways that this or that love can be healthy or “a demon” and the ways Eros can go wrong are given special attention. But he also talks at length about how Eros at its best creates, essentially, a naturally selfless love…all our attention, all our care goes toward the beloved.

We see this healthier Eros in one nice little moment when Frank, the cabbie, is asked if he likes Narnia, which he admits is a “fair treat.” Aslan asks him if he’d like to live there and without a moment’s thought he says, “Well, you see sir, I’m a married man. If my wife was here neither of us would ever want to go back to London, I reckon. We’re both country folks really.” In other words, Frank could never stay in Narnia—even if it were paradise itself—without his wife. In the words that Lewis would put in the mouth of Eros, “Better this than parting. Better to be miserable with her than happy without her. Let our hearts break provided they break together.”

Lastly, the divine love of Charity or ἀγάπη (agape).

Charity is love that comes only—and of necessity—from the divine source. Humans are able to participate in it by receiving it and in time can learn to gift it others as well. While the other three loves are what Lewis would call “Need loves,” Charity is all “Gift love.”

And, interestingly enough, Lewis sees the best example of this type of love not in the places where you might expect a theologian to go—not at the cross and Christ’s sacrifice, and not at the resurrection—but first and foremost in the creation of the world.

He says, “We begin at the real beginning, with love as the Divine energy. This primal love is Gift-love. In God there is no hunger that needs to be filled, only plenteousness that desires to give.” He goes on to explain that God didn’t create the universe because he needed people to manage, or because he needed worship, or because he needed a place to exercise his sovereignty. On the contrary, God doesn’t need anything. Charity is not about need. “God, who needs nothing, loves into existence wholly superfluous creatures in order that He may love and perfect them.” He creates the universe not out of need, but as a gift of love to the creation itself.

And yes, Lewis notes, God does this foreseeing the cost…pain, heartache, sacrifice, the cross.

Here we see Aslan plainly enough in The Magician’s Nephew. In Lewis’s imagination the creation is an act of joy, of beauty, of love. And Aslan’s first words to the creation are an invitation for them to become like Aslan: “Narnia, Narnia, Narnia, awake. Love. Think. Speak. Be walking trees. Be talking beasts. Be divine waters.”

And perhaps we see most clearly the power of love as Lewis describes the happy ending of the novel (and make no mistake, Lewis says himself that they were “all going to live happily ever after.”).

How are they made happy?

Well, Mother got better and Father—now rich—returns home, and the affectionate family which had been broken was made whole again.

And, “Polly and Digory were always great friends and she came nearly every holiday to stay with them at their beautiful house in the country.” Their loving friendship continued on throughout their lives.

King Frank and Queen Helen (along with the talking animals of Narnia) “lived in great peace and joy” and had children of their own.

Uncle Andrew went to live with Digory’s family in the country, an act of love offered by Digory’s father to give Letty a break from the old man’s presence. He never did magic again, as he had learned his lesson and over time became kinder and less selfish. But Eros still burned bright for him, as he cornered visitors to tell them about the “dem fine woman” with the devilish temper who he had known once upon a time.

And lastly, the divine creative force of Aslan’s love is worked into the happy ending itself, as the magic apple which healed Digory’s mother also grew to be a tree. When it fell during a wind storm, Digory couldn’t bear to just throw it out, and had it made into a wardrobe…which brought four more people into the loving orbit of Aslan.

Because love at its best—charity—is something too much for any one person. It fills us and overflows into the world around us. The creative power of love echoes down the generations, bringing blessing to unexpected places and unexpected people.

I don’t know that there could be a more fitting place to end our discussion of The Magician’s Nephew, so when we meet again we’ll dive in to—finally!—The Last Battle.

Until that time, my friends, may you find love in the world around you, as well as great peace and joy.

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.