Divide et impera. Divide and rule: the approach of choice for many historical conquerors, and also a great way to write a novel.

Breaking apart something that was once whole to examine the pieces provides the novelist with an approach fit for a whole range of subjects. I’ve found so many books following that pattern that I couldn’t begin to list them all. But the good news is that I’ve only been asked to talk about five here, so I’ve picked five that have lodged themselves in my brain, and showcase in how many ways the tactic can be used when it comes to the best science fiction and fantasy writing.

Divided Kingdom by Rupert Thomson

First published in 2005, Thomas’ vision of a United Kingdom chopped into quarters to house a populace divided by personality type is a dystopia full of ideas that feel ever more relevant. Once sorted into Humors (the Ancient Greek system of medical categorisation) children are relocated to live with families designated as similar in temperament. The main character, Thomas, is Sanguine—with his new, cheerful family he appears to thrive, until a trip over the border to the Phlegmatic quarter arouses old memories. For a country split apart by razor-wire boundaries and strict rules, Thomson finds beautiful moments. Or maybe that’s simply down to the exceptional quality of his writing.

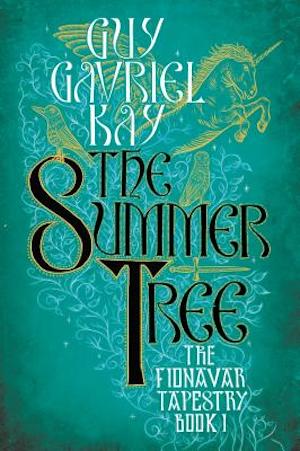

The Summer Tree (Book One of The Fionavar Tapestry trilogy) by Guy Gavriel Kay

The great divide that epitomises fantasy writing could be said to lie in the break between worlds—often found in that magical moment when a character steps from one reality into another—and one of my first experiences of being transported by portal fantasy came from the Fionavar Tapestry trilogy. I’ve loved it ever since. But not only for the way in which it, with pace, moves five teenagers from the University of Toronto to the land of Fionavar, where a vast battle between good and evil awaits them; it’s also the divisions that then form between the paths of the teenagers that has always appealed to me. Kay incorporates well-worn storylines, gods and goddesses of old, into his world, and then breaks them all apart to bring fresh emotion.

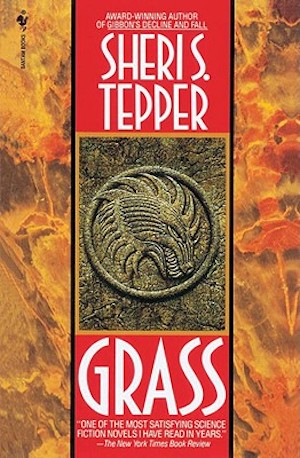

Grass by Sheri S. Tepper

If conflict really does drive drama, then the divisions of the class system have often been behind the steering wheel. Grass creates a society split into aristocracy and desperation. The nobles, ruling a planet of lush plains with an ecosystem they have not bothered to understand, are obsessed with horse-riding, and the highly stylised hunts they organise. They have no time for the plague that is sweeping the universe and yet, somehow, doesn’t seem to affect them.

How we cut up resources to suit ourselves, and deem some more worthy of those resources than others: this fundamental unfairness of humanity lies at the heart of so many SF/F stories that stand the test of time, possibly my favourite being Herbert’s Dune. I can’t wait to see Villeneuve’s film version of that, to find out what he chooses to stress and what he finds less relevant. How societies move on from their past literary visions, particularly when it comes to social and political concerns, is fascinating—have we moved on from Tepper’s Grass?

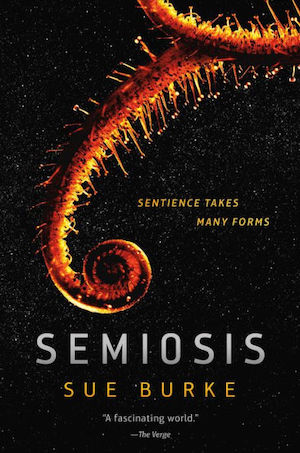

Semiosis by Sue Burke

On that thought, how far do we move from anything that’s gone before? SF and fantasy can approach this question with the freedom to traverse worlds and time to make its point. Semiosis takes a carefully layered, generational look at a group of colonists who settle on a planet far from Earth and must learn everything about their new home. Issues that one generation solves creates the problems of the next, and any solutions are hard-fought, involving difficult social change and compromise. Maybe what really divides the colonists is the chasm between those that want to become part of what already thrives on the planet, and those who want to dominate it.

This idea of human generational shift affected by a changing world is so potent; many of my favourite books fall into this category, including Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy—I’ve written about it before for Tor. I’m always pleased to find a new example, such as Marian Womack’s upcoming novel, The Swimmers, which shows how well this approach can also reflect on current environmental issues.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

Many of the divisions mentioned so far happen on a large scale, but there are some that are little more than fine cracks, barely noticeable, and it takes exquisite writing to make them visible to the reader. Often books that achieve this feel deeply truthful about what it means to be human. Personality is, perhaps, a collection of memories, thoughts and feelings, joined together with the cracks papered over in reality. In fiction, these cracks can be exposed. They can even be blasted apart.

The Memory Police starts as a dystopia, set on an island where a police force might enter your home and take you away, never to be seen again, for a very specific crime: remembering. Once all the islanders lose a memory of something—a small thing such as a ribbon, say—it is a crime to still be able to recall it. Why can some people continue to remember? But the questions that drive the first pages of the book soon give way to deep concerns about how much is being lost by each forgetting. The focus becomes the question of how much an individual can lose in this way before there’s no personality left at all. Ogawa brings in psychological horror brilliantly: everything can be divided, in the end, and there will be nothing left for the memory police to conquer. All that we are can be taken away from us.

Buy the Book

Skyward Inn

Aliya Whiteley’s novels and novellas have been shortlisted for multiple awards including the Arthur C Clarke award and a Shirley Jackson award. Her short fiction has appeared in Interzone, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Black Static, Strange Horizons, The Dark, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Guardian, as well as in anthologies such as Unsung Stories’ 2084 and Lonely Planet’s Better than Fiction. She also writes a regular non-fiction column for Interzone magazine. Her latest novel, Skyward Inn, is a classic science fiction story of division between worlds, states, families, and memories.