Let’s get into it, friends. Let’s talk about what really matters.

Let’s talk about death.

We’re here to start Pratchett’s very first Death-centered book, Mort.

Summary

Mort’s father Lezek and his uncle Hemesh are talking about what to do with him. He’s just a very strange young man who thinks too much and isn’t much suited to doing anything, plus he reads. His uncle suggests his father get him apprenticed, so he’ll become someone else’s problem, and they head to a nearby village where boys line up in the town square to become apprentices. No one picks Mort, but he waits all day unto the stroke of midnight, and Death arrives. He offers Mort a job as his apprentice, making Lezek think he’s being apprenticed to an undertaker. Before they go, Lezek tells Mort that apprentices sometimes inherit the business of the men they’re apprenticed to, especially if the man owning the business has a daughter they can marry. Death takes Mort to Ankh-Morpork to have a curry, and while Mort thinks to ask about how he can eat, Death goes off on an entirely different tangent—someone has drowned a bag of kittens, and he’s angry about how his job means he often doesn’t see people at their best.

They eat curry and get Mort new clothes and a haircut, and Mort wakes up the next day in Death’s house. He walks around and runs into Ysabell, Death’s adopted daughter, who is surprised to find he is real and alive, and decides to call him “Boy”. She takes him to the kitchen where the manservant Albert is cooking up breakfast, but before Mort can eat, he is summoned to Death’s study. He tells Mort to muck out the stables, though he fails to explain what this has to do with learning the secrets of time and space, as being Death’s apprentice is sure to impart. As he’s working, Ysabell comes to ask why Death would have taken him on as an apprentice, as Death isn’t something you become, it’s something you are. Once he’s finished, he goes back to Death’s study and asks him why he was told to muck out the stables. He realizes that it’s because Death is always up to his knees in horseshit. Death is impressed by Mort’s clarity, and asks if he’s met Ysabell, his daughter, who will of course inherit everything that’s his. Then Death tries to wink.

Buy the Book

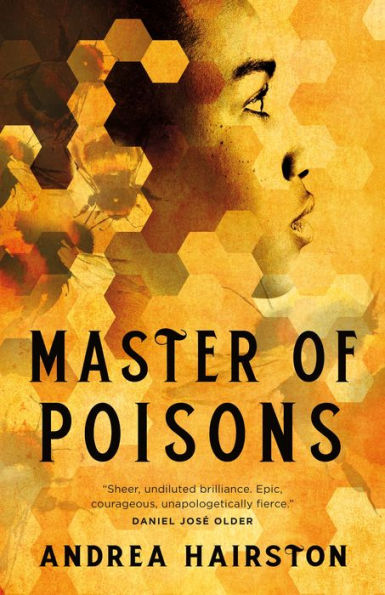

Master of Poisons

Mort spends some time with Albert, who is quite alive, though he won’t say how he came to be in Death’s employ, or why they seem to have a quiet understanding between each other. Death takes Mort out to do his job—he’s going to the assassination of a king in Klatchistan at the hands of the Duke of Sto Helit. Mort is full of questions—what sort of king the man is, why he has to die then, why Death uses a sword instead of a scythe here (kings get the sword on account of being royalty)—while Death is trying to explain that he’s merely there to do the job, not dispense justice. Mort tries to warn the king, but his pleas don’t work, as Death says they won’t. The king handles his death quite well, though he is worried for his daughter. As they leave, they walk through a wall, which almost kills Mort when he realizes that he shouldn’t be able to do it. He asks Death if this is magic, but that’s the one thing it isn’t, according to Death. The king’s morphogenetic field begins to weaken and he fades. Mort asks what’s happened to him, to which Death replies ONLY HE KNOWS.

Death explains to Mort that only the gods can interfere with who lives and who dies, and that attempting to alter it could destroy the world. Mort wants to know if he’ll be sent home, but Death isn’t displeased that Mort showed compassion—he merely tells him that he’ll have to learn the type of compassion suitable to the trade. After some time in Death’s home, where he occasionally goes out for the sake of “the Duty” of their trade, sometimes helps Albert about the place, and sometimes reads in the library, Mort asks Death for a day off. Death is surprised, but sends Mort to Ankh-Morpork for the day. Once there, he tries to get a fast horse, with the intention of heading to Sto Lat, but ends up menaced by a bunch of thieves who want the money Death sent him out with. Mort outwits them handily, knowing he’s not likely to die—he walks through a wall. In the meantime, Death is going through the upcoming deaths, one of them being a princess who is only fifteen. He decides he will send Mort solo to collect the next three deaths because he is feeling quite sad.

Mort winds up in a Klatchian household and allows them to think he’s a demon, asking them to get him a horse. The husband, who is a server at the curry place, tells the family they’re moving back home—because he just sold Mort the Patrician’s champion racehorse. Mort rides to Sto Lat, intending to talk to the king’s daughter because she’d seen him when he was invisible before her father died. But he can’t manage to walk through walls into the palace, so he goes to find a wizard, and meets Cutwell. He asks the wizard to help him figure out how to walk through walls, but Cutwell says that will take time and research. Mort gives him a gold coin as a down payment, then notes that it’s sunset and Death will be coming to collect him in the city, so he rushes from Cutwell’s home… but finds himself with Death as soon as his time’s up.

Book Club Chat

Pratchett has stated that Mort is the first Discworld novel he was personally pleased with, making some comment about how before all of his plots had existed to essentially hold up his jokes, and Mort was the book that changed all that. It is not at all surprising that the first Death book would be the tome that did it, I think, because the Discworld is a unique fictional universe, but Death of Discworld is something altogether singular even alongside that remarkable feat.

And of course, what really matters about Death is that he’s capable of being depressed.

There is always a question of whether we believe, from a storytelling perspective, that being a personification of Death would be a depressing job. And different stories have different opinions on the matter, whether they decide that Death is a function and therefore incapable of feeling any way about the work, or that having a job tied to literally the only fact of life—that everything eventually dies—is an inevitable hardship that takes its toll. But with Discworld’s Death it’s a bit more specific, namely in the fact that Death is aware that his job means that he’s often going to encounter the worst in people. We get that very explicitly with the section around the drowned kittens, and it comes early in the story as a way of framing the difficulty we’re going to see between Death and Mort.

There’s a weariness to Death from the outset of the story, which really culminates in the moment when he asks Albert about what he’s feeling, Albert tells him sadness, and he replies I AM SADNESS. Which always struck me because if you’re the personification of an aspect of natural order then… well, it just makes sense that your emotional states are more than just your brain doing chemicals. If Death is sad and he is becoming sadness, conceptually, that’s a lot, even for him.

There’s also the romantic aspect to this story between Mort and Ysabell, of course, which is made to mirror Great Expectations. (The fact that Ysabell calls Mort “Boy” is a tell to that end, as Estelle calls Pip the same.) And I have feelings about that because honestly, it is not a Dickens I’ve ever been overly fond of, but you could argue that Pratchett is trying to do Dickens one better here. Just to start, the set up is better—rather than a horrific bitter old woman keeping a girl locked away from the world, Ysabell’s adopted dad isn’t trying to make her life miserable with the world he’s created around her. He knows that she’s lonely and could use some company her own age. He’s trying to help in a very messy dad sort of way. So it’ll be fun to pick over the way Pratchett uses that framework to a better end, and actually creates a proper love story around it.

As a side note, there’s a thing I think about a lot, which is that Death’s decor is all done in purple and black. Which is just… it’s the thing, right? Like, I myself as a person with deeply goth sensibilities who still loves glitter and color, know that the goth color outside black is always purple. If a character who leans goth is wearing another color, it’s purple. (Occasionally there’s a splash of red, usually if they’re evil.) Ergo, Death’s house is black and purple. And white, too, because bones.

Asides and little thoughts:

- Obvious thing out of the way—Mort means death in French, we all know it, it’s very cute.

- This is the second time we read “million-to-one-chances crop up nine times out of ten” in the Discworld novels, which is something of a running joke for Pratchett that even predates Discworld—apparently it can also be found in The Dark Side of the Sun.

- Stuck on the idea of reannual plants, and being a gardener who knows they are planting things so that you can enjoy what you saw last year.

- When Mort tells Death that his clothes are new and Death’s response is IT CERTAINLY ADDS A NEW TERROR TO POVERTY, just, damn son. I think one of my favorite things about Death is how his sense of humor is something scathing and profoundly gentle all at once.

- As descriptors go, the idea of Ysabell being close to Pre-Raphaelite but with the “slight suggestion of too many chocolates” is something that I think many of us would strive for, or have possibly achieved. *reaches for chocolates*

- Mort’s way of dividing up the stables when doing his work is, indeed, a very useful way of thinking of anything, even if I can’t always get my brain to cooperate on that front.

- I love that Death says he gets his coins in pairs, as a reference to covering the dead’s eyes with coins. It’s just good.

Pratchettisms:

Tragic heroes always moan when the gods take an interest in them, but it’s the people the gods ignore who get the really tough deals.

The other diners didn’t take much notice, even when Death leaned back and lit a rather fine pipe. Someone with smoke curling out of their eye sockets takes some ignoring, but everyone managed it.

He blanched and muttered a few protective incantations after Death turned, very slowly for maximum effect, and treated him to a grin.

There were a lot of funereal drapes here, and a grandfather clock with a tick like the heartbeat of a mountain. There was an umbrella stand beside it.

It had a scythe in it.Three men had appeared behind him, as though extruded from the stonework. They had the heavy, stolid look of those thugs whose appearance in any narrative means that it’s time for the hero to be menaced a bit, although not too much, because it’s also obvious that they’re going to be horribly surprised.

Death had said that it was an acquired taste. Mort had decided not to make the effort.

We will be reading through to “Fut up!” next week.