Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

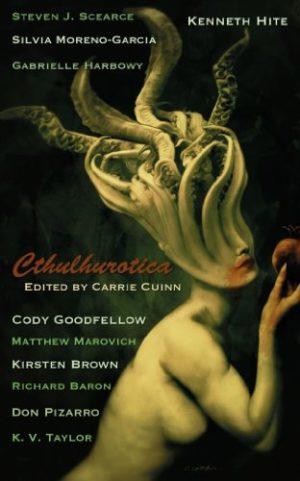

This week, we’re reading Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “Flash Frame,” first published in 2010 in Carrie Cuinn’s Cthulhurotica anthology; you can more easily find it in Ross E. Lockhart’s The Book of Cthulhu. Spoilers ahead.

“I looked at my steno pad and the lined, yellow pages reminded me of leprous skin.”

“The sound is yellow.” That’s unnamed narrator’s opening statement, explanation (if explanation is possible) to follow.

Back in 1982, narrator was a freelance journalist in Mexico City. In those pre-wire service days, he eked out a living providing articles for a range of publications, including an arts and culture magazine; however, it’s a “mixed-bag of crime stories, tits and freakish new items” called Enigma! that’s his chief source of income. Unfortunately, Enigma!’s new editor is picky. Narrator needs a story too sensational to reject.

He visits El Tabu, a once-grand Art Deco theater, now showing porno flicks and providing shelter to the homeless and the hustling. Projectionist Sebastian, a reliable source for sordid gossip, mentions a religious group that rents the theater every Thursday. The Order of something, as Sebastian unhelpfully names it, sounds like a sex cult to him. Sounds like because he’s never actually seen their services—they provide their own projectionist and confine him to the lobby. Still, he’s heard enough to doubt they’re worshiping Jesus.

The head of the Order is Enrique Zozoya—apparently a hippie activist in the ‘60s and a New Age guru in the early ‘70s. Since then he’s dropped out of sight. The lead’s intriguing enough for narrator to return to El Tabu the following Thursday armed with notebook and tape recorder. The notebook’s reliable; the old recorder sometimes switches on at random. Narrator hides on the balcony, peeking through a curtain as fifty worshipers enter. Zozoya, dressed in bright yellow, says a few (to narrator) incomprehensible words, then the projection begins.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

It’s a movie about ancient Rome as seen by ‘50s Hollywood, though with lots more bare tits. The actors are mostly “comely and muscled,” but background players have something “twisted and perverted about them.” Featured are an emperor and his female companion. The film lasts only ten minutes. Just before the end, narrator glimpses a flash frame of a woman in a yellow dress. Zozoya makes another inaudible speech, then everyone leaves.

Narrator’s underwhelmed, but returns the next week. This time Zozoya has a hundred congregants. Same film, new scene, this time a chariot race. But the dialogue’s missing—someone’s replaced the original soundtrack with new music and an undercurrent of moans and sighs. Near the end comes another flash frame of the yellow-clad woman sitting on a throne, blond hair laced with jewels, face hidden by a fan.

How is Zozoya collecting a congregation for some ‘70s exploitation flick shown only in snippets? Narrator goes to the Cineteca Nacional to research the film. He digs up nothing, but an employee promises to look into the mystery. The matter troubles him enough to dream about a naked woman crawling into his bed, wearing a golden headpiece with a veil. Her skin is jaundiced, its texture unpleasant. When narrator displaces the veil, he sees only a yellow blur.

Next day he feels unwell. His yellow notepad reminds him of the woman’s skin, and he gets little writing done. But Thursday he’s back at El Tabu, for his journalistic sixth sense suggests he’s chasing a worthy story. The new snippet’s set at a banquet, with emperor and companion overlooking naked but masked guests, some scarred or filthy. The guests copulate. Flash frame: the woman in yellow, fan before face, yellow curtains billowing behind her to reveal a long pillared hallway. She crooks a finger, beckoning. Back to the banquet, where the emperor’s companion has collapsed. The end. Narrator strains to hear Zozoya’s closing speech. It sounds like chanting, which the congregation echoes, all two hundred of them.

Narrator dreams again of the woman in the veil. She kneels over him, displaying a vulva of sickly yellow. Her hands press his chest, weirdly oily. He wakes and rushes to vomit. Next morning he can’t tolerate the yellow of his eggs, or of the manila folder containing his El Tabu research. He tosses both. After another nightmare, he’s weak and shivering. In the streets yellow cabs and yellow sunflowers so appall that he rushes home. A fourth nightmare, in which the woman gnaws his chest, wakes him screaming. He knocks over his tape recorder. It starts playing the movie’s soundtrack, which the machine must have recorded last time. He’s about to switch it off when he hears something that shocks him.

At El Tabu, the congregation’s swelled to three hundred. The snippet’s of a funeral procession for the emperor’s companion. Torches show men and women copulating in the background, not all of them with “anything human.” The emperor rides a litter with the yellow woman, who lifts her veil. It’s the shade of bright flames. The emperor—and narrator—look away.

Next day the Cineteca employee calls. She’s discovered the film is called Nero’s Last Days. They have a copy in their vault.

In March 1982, narrator notes, the Cineteca archives burn for sixteen hours before firemen extinguish the blaze. El Tabu burns down also. The reason is what he heard on his recording, what the machine caught that his ears couldn’t. The real voice track of the movie was—yellow. Noxious, festering, diseased, hungry yellow. Speaking to the audience, telling things, demanding things, “the yellow maw, the voracious voice that should never have spoken at all.”

Warning signs are yellow, and narrator heeded the warning.

Now narrator’s an editor for that arts magazine. He’s covering a Cineteca Nacional retrospective that will include—a rare print from the collection of Zozoya’s widow, of guess what film.

Since 1982 the Cineteca’s gotten higher tech vaults, but narrator’s learned more about chemistry. This time it’ll take the firemen more than sixteen hours to extinguish the fire.

What’s Cyclopean: Yellow yellow yellow yellow golden jaundiced yellow leprous bright noxious yellow festering yellow insatiable yellow

The Degenerate Dutch: Everyone here is degenerate; most of the story takes place in a porn theater.

Mythos Making: For all its serious artistic flaws, we find The King in Yellow translated into opera, paintings, and now film. Truly a multimedia franchise.

Libronomicon: Read Enigma! for true crime, tits, and “freakish news items.” And, we guess, arson.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Once you start tossing out perfectly good eggs, something is definitely wrong.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Ah, The King in Yellow. Never a bestseller, but perennially in print. Read and discussed around the world, translated into every language. (Every language.) Adapted for stage and screen—and thoroughly recognizable, even when the title is changed. A dangerous king is a dangerous king, right? Or queen.

Our last encounter with That Play was Fiona Maeve Geist’s adaptation to rock opera. But in every incarnation, it has much the same effect as Cthulhu shifting in his sleep: madness, art, and the overturning of the status quo. But because Lovecraft and Chambers had very different ideas about dangerous revolution, Cthulhian uprisings may be somewhat sympathetic to the non-imperialist reader, while Kingly uprisings are distinctly authoritarian. “The Repairer of Reputations” gives us the original of this pattern, borne out in Robin Laws’ expansions. Alexis Hall’s The Affair of the Mysterious Letter (too long for this column, but awesome) portrays a post-revolutionary Carcosa more hazardous than the Reign of Terror.

And Silvia Moreno Garcia gives us… something ambiguous. A yellow journalist watching a dangerous play from hiding in the back of a porn theater. A 2-bit demagogue who’s gotten hold of something real, attracting followers to watch clips of the sort of coupling that would give Lovecraft nightmares, and give the world… what? We never see what the followers do outside the theater, in response to the insatiable demands of the film’s voice track. We never hear what their leader tells them. And we don’t, in fact, know if what the tape recorder picked up is the same thing they heard. Are they all having dreams of squelchy yellow queens coming on to them, or is that just narrator?

And if they are having those dreams… what happens if you actually let her have her way? What actually scared Lovecraft wasn’t so much the coupling as the result of the coupling—what happens, say, 9 months later? Parasitic breeders, man. Can’t live with them…

The only clear result of the movie that we see, in fact, is the narrator’s growing taste for arson. Sure, each case he describes is intended to destroy a specific print of the film. But (1) I trust that about as much as I trust any claim made by someone who’s encountered That Play, and (2) there’s an awful lot of collateral damage, and by the end he seems to revel in it. Can shouting and killing be far behind?

Because that’s the thing about That Play. Once it’s shaped you, even your attempts to rebel against it are tainted. Are maybe even playing into what it wants. In “Repairer,” both sides of the incipient conflict ultimately serve the King. In “The Yellow Sign,” we can’t be sure of exactly what happens, other than that it’s painful and unpleasant for everyone involved. And that it serves the King.

For my money, That Play is far more terrifying than Cthulhu. Because you could have chosen to do one seemingly trivial thing differently—take a different book off the shelf, go after a different sordid story—and you’d have been fine. It’s the ease of making a little mistake, and paying everything for it, that we can only wish was limited to fictional theater. It’s the system that’s so big you can’t imagine changing it, ready to crush you into an extra grain for its insatiable maw. It’s the uncaring universe made paper or melody or celluloid, and compressed into portable form for your personal edification.

And everything you believe afterwards, everything you do to resist and serve it, will make complete sense.

Anne’s Commentary

Welcome back to the world’s scariest color. Have we seen the Yellow Sign? We have, many times. How about the King in Yellow? He’s an old friend, along with Howard’s High Priest Not to Be Described, who lurks deep in an ill-famed monastery on the Plateau of Leng, a yellow silk mask over his, or its, face. We’ve even made the acquaintance of a canine Yellow King in “Old Tsah- Hov.” Surely we’re overdue for a Yellow Queen?

We need wait no longer, for this week Silvia Moreno-Garcia serves Her up in the modern medium of celluloid. Twentieth-century cultists didn’t have time to scour musty antiquarian bookshops for an obscure play printed on paper as jaundiced as its titular monarch. It was much simpler for them to repair to a musty porn theater. Forget about reading a whole first act to get to the juicy second one. It was much less trying to the attention span to take their insalubrious entertainment in movie form. Zozoya didn’t even demand his followers sit still for a couple hours—instead, a forward-looking hierophant, he dished up vlog-length portions of ten minutes or so. And, like a savvy YouTuber, he saw his followers increase each week. Think what he could have done today, with a real YouTube channel, new videos uploaded every Thursday, don’t forget to like and subscribe and comment below on your rad nightmares!

Upon more sober consideration, maybe we don’t want to think about that. Social media would have given Zozoya a platform sufficient to start a world-consuming saffron conflagration. The pyrotechnics of “Flash Frame’s” narrator would have been pathetic sparks in comparison.

The King in Yellow is a frank demon, for He only appears to wear a mask—that’s His real face, Cassilda! Like Lovecraft’s High Priest, Moreno-Garcia’s Queen wears a yellow veil. This concealment, I think, makes them even more terrifying. What do they have to hide, how soul-wrenchingly hideous must they be? The Queen may actually up her scare-factor by being so unconcerned about revealing the rest of Her body, to its most intimate parts; and they’re scary enough, being coarse-textured, oily—and yellow. A yellow so diseased it infects with dread all the wholesome or cheerful yellows of narrator’s world, from egg yolks to taxicabs to sunflowers. More tellingly, it contaminates the yellows of his trade, steno pad pages, manila folders.

This Queen, this Yellow, is contagion itself. She and It are not content with poisoning sight; they also inflict the synaesthetic punishment of generating yellow sound, a maddening super-aural sensation that can only be consciously perceived via recorder playback. A machine has no emotional filters, no self-defensive deaf spots. Zozoya deliberately uses technology to serve his Queen; accidentally, technology reveals and thwarts Her.

Temporarily, locally, thwarts Her, I guess. Aren’t temporary, local victories the best we can hope for when faced with hungry cosmic horrors and contagions from beyond? Colors out of space, “yellow” as well as “fuschia” to our poor primate brains. “Queens” as well as “Kings” to our primate notions of hierarchy and sex. We have only metaphors for their realities.

Like other writers we’ve seen tackle yellow as the scariest color, Moreno-Garcia employs all the descriptors of disease: Her yellows are jaundiced and leprous and sickly and festering and withered and noxious. Reminiscent of pustules bursting open. Warning signs. Yellow cabs look like lithe scarabs—the sacred scarab of Egypt was a dung beetle, and aren’t both insects and dung associated with contagion? So is unprotected sex, like that practised in the orgies of Nero’s Last Days (where some participants are scarred or filthy or outright inhuman) and that implied by the Queen’s dream-assaults on narrator.

Contagion of the viral type is much on our minds these days, both in the biological and media senses. Is this what made “Flash Frame” particularly unsettling for me? I think so. From behind my masks, actual and metaphorical, I do think so.

Next week, Craig Lawrence Gidney’s “Sea, Swallow Me” raises questions of oceanic origins. You can find it in the author’s collection of the same title.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.