Here’s what I know. Four days after Breonna Taylor was murdered, my county effected a shelter-in-place mandate. My second book was delayed, then undelayed, then delayed, then released in April, but all my signings and events were canceled. I watched the body count get higher and the list of people being laid off get longer and the disregard and disdain from those who remained blissfully unaffected get deeper.

The day George Floyd was murdered, I finished reading Bethany C. Morrow’s A Song Below Water. It filled me with love and righteous fire and I couldn’t wait to write my review. Hours later I was doubled over in pain worse than anything I’d felt before. I couldn’t sit, couldn’t stand, couldn’t lay down.

The day Tony McDade was murdered, I was laying in a hospital bed waiting on test results. The peaceful protests and brutal police retaliation erupted, and I could only watch, feeling helpless and enraged at the same time. A few days later as others were being beaten and arrested and shot at, I went home to recover from surgery. I had my family by my side. Taylor, Floyd, and McDade did not.

And now after a week of protests, change is happening in fits and starts. I cannot march in a protest, and I only have so much money to donate, but what I do have is a voice, a platform, and a love of Black young adult speculative fiction. I don’t know what I can say that hasn’t already been said by activists more informed than I, but I can use this opportunity to honor our culture and the people doing the work. Lately, every moment of my life is swallowed up in Black pain, so I want to take a moment to celebrate Black joy. To do that, we need to talk about A Song Below Water.

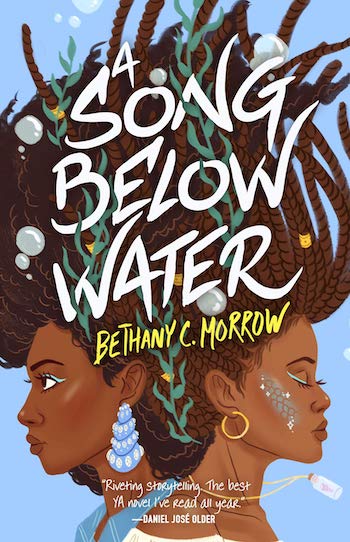

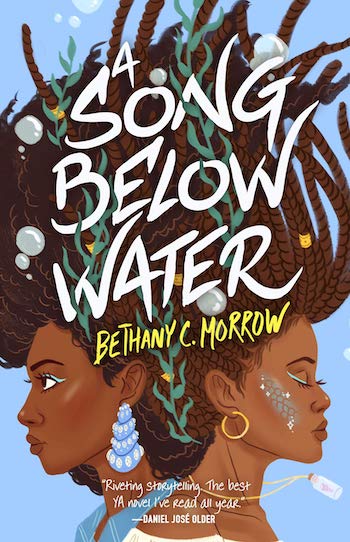

The story unspools around two Black teen girls confronting systemic oppression, anti-Blackness, and police brutality. One girl, Tavia, is a siren. With her Voice, she can make people do things they normally wouldn’t do. That power would be fearsome enough on its own, but because most sirens are also Black women, being a siren is equated to being a weapon. Tavia follows the orders of her overprotective parents and keeps her true self a secret. Even as her throat burns to release her Voice, she stays silent.

Effie is human, as far as she knows, but she deals with the grief of losing her mother and never knowing her father. Her self-esteem is shattered by a mysterious skin condition and the guilt at being connected to several incidents of humans being turned to stone. Blocked from accessing her history by her grandparents, Tavia cannot see the future coming at her. Her family only wants to protect her, but they all learn the hard way that protection cannot be won through ignorance.

Buy the Book

A Song Below Water

Then a Black woman is murdered by her boyfriend and is posthumously accused of being a siren. Then, when pulled over for the crime of driving while Black, Effie is forced to use her Voice on cops threatening violent escalation in order to extricate herself from potential harm. Then a popular Black YouTuber comes out as a siren and walks with them in a large march for the murdered woman. Then a protest against police brutality turns violent as peaceful protestors collide with agitating cops. With Tavia’s freedom at risk and Effie’s mental stability fracturing, the girls must work together to save themselves, not just from those who wish them harm but from a tyrannical system determined to punish them for daring to speak out.

Early on in the book, Effie sits through an uncomfortable classroom conversation every Black kid in a predominantly white school will recognize. While her teacher is specifically talking about Black sirens, the pattern of the discussion is the same. The teacher begins talking about civil rights and civil liberties which devolves quickly into victim blaming, assimilationist rhetoric, and bootstraps ideation, with a sprinkling of Black exceptionalism and “we don’t need affirmative action anymore” for good measure. Black sirens have an unfair advantage, you see, over “normal” people. It doesn’t matter whether they use their powers or not. That they can is seen as a break in the social hierarchy, not just because they’re sirens but because they’re Black women sirens. They are condemned for not assimilating and then denied the opportunities to participate in society. So they’re collared, their voices stifled and their bodies physically marked as “other.”

Morrow does not describe the siren collars in detail, but my mind immediately flashed to the heavy iron collars some enslaved Africans were forced to wear. These collars, worn for weeks or months at a time, often had three or four long, pointed prongs sticking out, frequently with bells attached, making it painfully difficult to sleep, sit, or labor. I also thought of Escrava Anastácia, the enslaved African woman in 18th century Brazil whose image – an illustration of her face muzzled and her neck collared – went viral recently when a white woman used it to compare the coronavirus lockdowns to slavery.

Effie and Tavia live in a world exactly like ours except mythical beings like elokos and gargoyles and pixies are common, although some are tolerated more than others. In particular, the girls reside in Portland, Oregon, a city that is 77% white and 6% Black (as of the 2010 census) and that has a long, tumultuous history of racism and anti-Blackness. Effie and Tavia are survivors in a society that does not care about them. They, like countless Black women before them, face the worst of what the world has to offer and stand strong against it. They have carved out their own spaces of peace and self-care amidst a world that wants to punish them for having the audacity to be both Black, female, and powerful. But they also fight to be believed, to be heard.

Like, Effie and Tavia, I have lived almost all of my life in predominantly white spaces. I’ve seen white store clerks follow my Black mother through stores. I’ve seen white cops come to our house, hand on gun, soured with suspicion even though it was my mother who was reporting the crime. I had to listen to white classmates assume my mother was a welfare queen even though she has a Master’s degree and a better paying job than their parents. Even in the hospital I was walking that tightrope of needing help but not wanting to seem demanding, of trying to express what I was feeling while making sure the doctors and nurses believed me. I’ve seen white doctors and nurses brush aside my Black women’s pain and I was terrified they would do it to me.

In nearly every job I have ever had, I have been the only or one of the only Black people employed. And the only Black queer woman. Every time I speak out against some new bit of systemic oppression or racial injustice, I have to navigate an obstacle course of questions. Will I be labeled an Angry Black Woman? Will I be heard or ignored? Is the cost of speaking out more than keeping my mouth shut? How many white people will publicly support me and how many will just send me emails full of “YAS QUEEN” and “get it, girl.” I’m already far less likely to be promoted to positions of leadership, but will this quash what few opportunities there are? Can I trust the other BIPOC in the room or have they allied themselves with white supremacy to get ahead?

That last question is a big one, and one I’m happy to see Morrow engage with. Learning that not all skinfolk are kinfolk is a hard lesson for those of us in predominantly white spaces. We’re so desperate for BIPOC kinship that we often make the mistake of seeing the sheep’s clothing but not the snarling wolf underneath. Some will throw you under the bus in the name of white supremacy. Some will drag the Model Minority Myth out as a battering ram. In the book’s case, we see Naema, the brown-skinned girl who wears a siren collar as a joke, and Lexi, the siren who made herself a reality star by “willingly” wearing a collar. How does a young adult stand up to a system so massive and powerful that it corrupts your own kin?

This young adult fantasy debut could not have been released at a better time. A Song Below Water isn’t just a story about The Struggle™. Morrow gives teen readers something to hold onto right now and something to work toward for the future. She offers more than a story about race or racism. Using the tropes of fantasy, she digs into the nuances of Blackness, of being a Black woman in a white supremacist and patriarchal society, of intersectionality, of systemic oppression, and state tyranny. Protest is more than fighting back with chants, posters, spray paint, and bricks. It is using our words to give hope and inspire the next generation.

Change is coming whether the oppressors want it or not. For many Black teen girls, A Song Below Water will be the boost of confidence they need. It walks them through intersectional oppression by showing them fantastical versions of their everyday lives. And it shows them how to be their best, Blackest self, in whatever form that takes. To my young sisters who are new to this fight, we welcome you. We are angry. We are tired. We are hurting. We are crying. We are filled with four centuries of fire and resistance. We are our Black enslaved ancestors’ wildest dreams and white supremacists’ greatest nightmare. We are the shield and the sword. We are the voice and the thought and the action. We will be heard, one way or another.

A Song Below Water is available from Tor Teen.

Alex Brown is a teen services librarian by day, local historian by night, author and writer by passion, and an ace/aro Black woman all the time. Keep up with her on Twitter and Insta, or follow along with her reading adventures on her blog.