A young academic has been granted permission to travel to a mining outpost on a small planetoid far from the sun to study the culture of a small squatter population that lives in total darkness.

“It is a simple prescription. Avoid the darkness.

It is a simple prescription, but you will not follow it.”– Loren Eiseley

The company pounder jostled down a long tunnel in the bowels of the rock. Its eight legs drummed a steady rhythm that Chocky felt in his bones. When the tunnel curved, and the pounder changed direction, the bodies inside it kept moving. Thing called momentum. Chocky didn’t know how many there were. The pounder could hold two tons of ore; instead it was full of people. Those on the outside of the huddle slammed up against riveted walls, caked with frost from their breathing, so cold that skin stuck to it and got pulled off in strips when yanked away. The ones who touched the walls fought their way inward desperately, biting and clawing and kicking toward the warm center of the huddle. Those nearer the center clawed back. Chocky fought savagely, thinking he could feel himself dying but never really sure. His numb parts were hatched by cuts, marked all over by sores and bruises.

Chocky couldn’t die. Not while the virgin needed him. He was her servant, and he felt for her a ravenous, insatiable need.

The pounder was never meant to hold living, breathing creatures. The company liked to improvise. Chocky felt a curve in the tunnel, a change in the rhythm of its claw steps, and he braced himself for another round. Fear and lust and fury, a turning heat between his ears. His breaths were shallow, his heartbeat was slow. No sight, no vision. He lived in a darkness so total that he had forgotten the word for it. No need to distinguish between dark and not-dark. There was only the ashen touch of skin-on-skin, the sounds of bodies, moving and breathing and farting. Murmured threats, sexual moans, bawdy anecdotes intermingled. On top of that, distant rhythms: the churning servos of the pounder; the machines of the company grinding the rock’s mineral flesh to slurry; the rhythms of distant sounders feeding it all back, turning it into song. He barely felt it, but it was enough.

Chocky’s left side began to burn. So close to the edge, he needed the warmth of the center. He sidled inward, looking for crevices in between flesh. Skin like stretchy fabric. Bite into it and it comes apart.

Chocky tongued his sharpened teeth.

Buy the Book

The Tourist

The tourist’s first days on the rock were worse than jet lag, worse than planet lag. It was not a place with a time difference, where days were longer or shorter. It was a place with no days at all. The last stop, the outpost farthest from the sun, a lifeless rock with no name but a long and unpronounceable string of digits. The sun was only one star among many, barely brighter than the rest.

“Please understand. This outpost was meant to be run by a skeleton crew. Two thousand miles of tunnels, a hundred thousand autonomous mining systems, radiation levels that can be fatal after a week of exposure. Those were the conditions that the company prepared for, and that was challenging enough.”

The company representative felt pressured to answer for an ore hauler full of dead Squatters. The tourist let her speak, stunned by her corporate ambivalence in response to so many deaths, but afraid to say a word in response for fear that their request to go underground, into the tunnels, would be declined.

The tourist had to remember not to call the Squatters “moles.”

“The original design called for a crew of no more than fifteen, working yearly shifts. Due to acts of violence against company employees and equipment, we now have a full crew and an additional ten-person security detail. So long as the Squatter population continues to disrupt mining operations and to endanger company employees, we are forced to take action with what we have available.”

The asteroid’s surface was a crust of water, ice, and gray rock, never-ending twilight under a too-bright tapestry of stars. No sky, no clouds, no swirls of dust. There was barely enough gravity to keep a body from floating away if it jumped, just enough to pull it back after a journey of slow, drifting hours.

“If the Squatters continue to sabotage our operations, if they do so much damage that the operation is no longer profitable, then the company will be forced to close it down. Where will that leave the Squatters? They can’t take over. They don’t have implants. They’re ignorant, violent, cruel. We may then be allowed to evict them, at last. But until then they are, technically, legally, autonomous. They are not our responsibility until they do enough damage that we are forced to take action.”

The rock was an island nation of exiles on the dark edge of space. A population of stowaways settled on the rock in the early days of the outpost’s construction, before the first company overseers arrived. They lived in the tunnels themselves, surviving lethal radiation by crude but effective genetic modification. They cultivated water and oxygen from deposits of ice. They siphoned food from the stores left for company operatives.

When the operatives arrived, they found themselves severely understocked, and they lived on minimal rations for the two years before the next shipment arrived.

“This terrible accident with the pounder, for example. No employee was involved. Strictly autonomous. You won’t believe me, but I’ll tell you anyway. Whatever happened in there, they did it to each other.”

The surface installation was lead-plated. The Squatters lived underground, unprotected.

“Do you know what they call the other colonies? Prison planets. That’s what they say. They think that they’re the ones who are free.”

The tourist brought their own suit, specially designed. No lights. The moles hated lights.

“They don’t want law or order. Even responsibility. It’s a cultural thing. Really.”

The suit had heavy radiation shielding, 3D imaging mapped by infrared depth-mapping, a power supply that would last for weeks. Non-lethal defense systems, an array of protective countermeasures. Multiple redundant sensory feed backups. It could walk the tourist back to the surface by itself if anything were to happen underground.

“I know that this sounds callous and insensitive. I know that I can’t convince you to stay on the surface. You’ve been given permission to conduct research, and I won’t try to dissuade you. But please, be careful down there.”

The tourist left as soon as possible, and went down. They saw their first mole in the elevator, the last place where there would be light. Its age and sex were indistinguishable. Folds of skin hung loose and floated, bobbing along with subtle vibrations, drifting as if suspended in liquid. It was pale, very pale. The tourist stared at it from behind the opaque globe of the suit’s visor. It did not react. Although blindness was not congenital, the tourist wondered if it could see at all, if the use of its eyes had been lost to atrophy.

Chocky flung his way along the Promenade one great thrust of his arms at a time. He encountered other unseen Squatters sharing rungs on the long ladder. Passing in pure darkness, they heard, smelled, and felt each other. They muttered chants and obscenities. Their bodies collided and bounced away, never accidently. Hands grasped at Chocky’s face, pockets, genitals. He struck with arms and elbows and they struck back at him before parting, sometimes with metal stubs and short blades. The cuts and bruises marred and softened his already ravaged skin.

The violence was a ritual, the most common and mundane social interaction of any crossing of the Promenade, any trip along a high-traffic ladder. He traveled as far as he could, as fast as he could.

The rock could be traversed by hand in a week.

The virgin would be dead within days.

Chocky could not bear the thought of losing her. If she died then he would die.

There were elevators and pounders that could make the trip in a day’s time, but company security kept them locked down. Chocky knew of shortcuts and rail riders run by Squatters, but they ran on barter. Chocky had nothing to barter.

Exhausted and sick with worry, Chocky stopped and found a tube bar. The stink of sex and fighting and sickness. Gentle hands found him in the dark and he let them explore. Their kindness was gratis. He floated into a corner and made himself small, wondering if he would give up his body for a stupor, and what else might be asked of him if he were to sell himself to get to the other side of the rock. He wept, silent and ashamed.

He heard the soft whine of servos and a singing, synthesized babble translated from the language of some other place. A tourist. The first that he had seen in the tunnels in some time.

Chocky followed the sound of it as it moved. In the gritty surface of the wall he could feel its heaving motion. Loud and clumsy, bumping against everything, clearly unaccustomed to low gravity. A breathing apparatus served the suit’s occupant with deep, high-oxygen breaths. Inside the suit he imagined an animal formed entirely out of lungs. He set off from the wall and drifted, then kicked toward the suit. He sidled up next to it, heard it say, “If you don’t mind…”

The words made Chocky laugh. Then he pushed closer and bumped his shoulder against a firm metallic carapace.

“Excuse me,” said the tourist. Sickly polite.

“Oh,” said Chocky. “My apology,” he said, in dimly remembered prison language. “Welcome stranger.”

The tourist turned to face Chocky and spoke in rapid dialect, untranslated. Chocky reached out to touch the tourist’s lips, to silence it. His fingers bounced against the visor and were numbed by a mild shock. Chocky pulled his hand away and the tourist recoiled. The tourist continued to speak rapidly, words that Chocky didn’t understand.

“I don’t speak so well,” Chocky said. “Use translator.”

The tourist obliged and rattled off a flurry of apologies. “I am so so sorry,” the tourist said. “This suit, it has protective modules. And I thought that you could speak.”

“Only a little. It is no problem. Didn’t hurt.”

“I know only a few words of mole language.” Chocky winced at the word. “It is a difficult way of communicating,” the tourist continued, “with idiosyncrasies unique to low pressures, low oxygen. Truly unique.”

“Yes, yes.” Chocky sucked on his finger, tasted dirt. Felt nothing in the nub.

The tourist stopped talking and Chocky heard its servos hum.

Chocky saw a ghost. The sight of it made him gasp. A cloudy phantom shape moved in the air, turned and tilted toward him. No, not a ghost, but a faint glow from the tourist’s bulbous head. Not a light, not so painful as light, but an emanation from the visor that left long red trails in his vision.

“I am sorry, again, so sorry,” said the tourist, and Chocky realized that it could see him, truly see him, perhaps by the dim glow, and that it had seen the face he made at the sound of the slur. “I did not mean to cause offense. The, umm, translator must have misinterpreted.”

Chocky smiled for the tourist, felt for a dispenser and tapped it with a knuckle. A thin tube wormed into his grasp and he slipped it into the corner of his mouth. A sour tang tickled his gums. “No harm,” he said. “None at all.” He heard the tourist fidget, looking for words. The luminous blur of the visor floated in the dark. “What are you looking for in these tunnels, spaceman?”

“I am here for research.” The tourist paused, waiting for a response that never came. “For my PhD thesis. My subject is Squatter culture. Your culture. How it may be shaped by your unique environmental and physiological conditions.”

“Yes. Physiological.” Chocky stretched his face into a wider grin. “Squatters? You mean us moles?”

The tourist squirmed and mulled over a response. The shape of its visor was plainly visible to Chocky by then. His weak eyes tracked it easily. In the corner of that shape he soon saw another, a blob of pale white that moved across the curved surface as the tourist shifted.

Living in darkness, Chocky’s appearance meant nothing to him. Yet he found himself leaning closer, cocking his head, staring at his own reflection—his own face—which he had not seen in—

“The Squatters, yes. There have been no first-hand accounts, only simulations. Even my professors know next to nothing. Tell me: Do you know Squatter music? The sounders?”

“You want to know about sounders?”

“My focus is on extraterrestrial ethnomusicology.”

Chocky laughed and slapped the dispenser. “Funny words,” he said. Prison language. Another tube found his fingers and he brought it to his lips. “You are very smart, spaceman.” He sipped fermented worm pulp from the tube. He didn’t feel the burn of alcohol. Just the effects. “Sounders. I know all about them. Pay for my tab, yes? Let Chocky show you around.”

Servos whined. Metallic clack. Fingers touching, maybe, the bounce of the head. Something called a nod. “Thank you, Chocky,” the tourist said. Then it laughed. Coins jingled in the dark. “An economy of physical currency,” it said. “Remarkable.”

“Here, spaceman. Put your hand here.”

Chocky’s fingers brushed the elastic thread of a map net. He felt it hum. Far from the Promenade, or any avenue, Chocky traced their route by knotted markers and vibrations in a dense web of synthetic coil. He motioned for the tourist and struck a taut length of cord.

“There. Feel it?”

Chocky knew when the tourist grabbed hold because they gripped too hard. The pressure of their digits muted the sensation.

“The rope? Yes, I feel it.”

“No you slag, not the rope. Pulses. You can feel it here, in the cord. It’s strong. Means we’re going the right way. Understand?”

The tourist twitched. Their grip on the rope loosened, tightened, loosened again. The vibrations that Chocky could read like signposts stilled and returned each time.

“You feel it?” the tourist asked. “Sound in the rope?”

“What, you can’t?”

“Vibrations. I see.”

Chocky laughed and kicked away, following the knots and turns of the netting. Following them he aligned his course through a three-dimensional maze.

He told the tourist about the early days, Squatting in the empty mine. How he got there, what he did. Some of what he said was true.

They heard someone scream in the dark. The tourist stopped. Chocky did not. After a moment, the tourist continued.

“Did you hear that?” the tourist asked.

“I did.”

“Do they need help?”

“No. Just tell me if you see anything, yeah? Keep behind me or beside me, all times. Don’t go looking at anyone with that glass face of yours. If someone comes at you don’t get nervous.”

The tourist laughed, for once. The sound was loud and gasping. “For what I paid for this suit I almost hope that they try. You are sure that they are okay? The one who screamed?”

Chocky did not answer.

“How old are you, Chocky?”

Chocky shrugged and spat. “Doesn’t matter.”

“Forgive me. But—are you a man or a woman?”

“What’s it smell like in that suit of yours?”

“Smell?” Pause. “Doesn’t smell like anything.”

“But you got a weak nose, like your fingers I bet.”

Then Chocky heard the tourist gasp. It tried to stop moving by grabbing on to the netting. Its momentum sent powerful tremors through the lines that sent Chocky spinning out. He gripped the netting with his fingers and toes until the motion stilled.

“What did you do that for?”

“Do you see that?”

“I don’t see anything,” Chocky hissed.

“Yes. Of course. But there’s something—hello?” The tourist’s voice raised an octave, increased in volume.

Chocky heard it, then. Shuffling, groaning, the rip and tear of clothing. He grimaced. “Leave them be. Their business. Not ours.”

“What are they doing? There is blood. They’re covered in it.”

“Then they’re almost finished. Whatever it is. Don’t get in the way.”

“I should do something.”

“You should mind your own business.”

“We should alert someone.”

“There’s nobody to alert. Come. We’re almost there.”

Chocky launched himself forward through the netting. He felt no disturbances in the lines. Behind him the tourist quietly said, “They stopped.” And then he waited for the tourist to catch up to him.

Anywhere in the colony, Chocky felt vibrations. It was carried through the rock, barely audible as sound. The timbre of minerals and hollows, oscillations of mining machinery. The loops of the sounders above it all.

The vibrations in the tethers of the web grew stronger. Dense, pulsing patterns built up and multiplied. Harmonies and polyrhythms.

“We should go back,” the tourist said.

“Don’t be dense. We’re here. You feel that?”

The tourist was quiet for a moment, then said, “Yes. Yes, I do.” A hint of excitement, perhaps, in its synthesized voice.

The tunnel opened. The air changed, growing thick, heavy, and damp. The hot smell of bodies. The death smell of rot.

“You’re lucky not to smell it,” Chocky said. “But I don’t envy you having to see it.”

“It is incredible. How many are there?”

“Don’t know.”

“Are there sounders here?”

“Could be. This they call a resonance. The sounders make their own speakers, some of them. Wind copper wire around big magnets, make them thump. Bury them in the rock so they can be felt all over. Others come to be close to it.”

“I see them. Maybe. There are so many. Some are listening. Others are doing—oh no.”

Chocky turned away and put his hand against cool, smooth crystal.

“I’m going to pay my respects.”

“They are doing terrible things,” the tourist said.

Chocky kicked away, drifted for a time, and hit a bare spot in the rocky enclosure. Cool and wet to the touch. He wondered what the tourist saw, the shape of the space, how many dozens, or hundreds, were assembled here. What they did to each other in the dark. He put his hands and face against the rock and felt the heartbeat of his world. The churning of machinery and the feedback of his people, muddied into a constant thrum. He thought about the pasty blur of his face, reflected in the tourist’s visor. It became the face of the virgin, the source of all pain and salvation.

Somewhere in the hum was the beat of her small heart, carried to him through miles of crust. He believed that he could feel it, growing weaker.

He kicked back and returned to the tourist, finding the spot by memory.

“I can hear it,” the tourist said. “But I must transpose the frequency to do so. The audible range is outside of human norms. Some have speculated that the air pressure is too low here for there to be audible sound. That is how little they know.”

“Let’s go. We have to go.”

“I do not want to stay here. But, tell me. Can you hear it?”

“Yes. Hear it here, hear it everywhere. It’s in the rock. Whole damn thing. Now we have to go.”

The tourist was quiet. Listening. Chocky listened too. In the cacophony of the resonance he heard other, closer sounds. Flesh on flesh. Grunting, moaning, crying. When it spoke again, the volume of its voice was very low. “My interest is anthropological.”

“Big space words. Use mole words so I can understand.”

“You said that we should go. The ones who make the music. You call them sounders?”

Chocky thought for a moment and nodded for the tourist.

“You know one?”

“I know lots. You want to meet one?”

“It is important for my thesis.”

“Then we go.”

Chocky drifted in void. An ocean of sound, and him floating on the shimmering surface.

“None of my professors have heard this before. There are no recordings. Not until now. This music has roots going back centuries. Early ritual music. Twentieth century drone, minimalism, musique concrete, electroacoustic. It is communal, spatial, improvisational. Wholly remarkable. But what horror. I’ve never seen anything like—”

Metal clicked on rock. Movement in the dark. Chocky followed cords and tags to a stall in a market wall. “Here, spaceman,” he said. “You want to make good with the sounder? We’ll go to them with gifts. You barter for it.”

Chocky heard the clink of coins and the thanks of the merchant. He could hear the merchant’s smile, a tightness in the voice, for the amount that the tourist overpaid.

“What are these objects? Are they significant?”

“Booze and batteries. Give them to me.”

Chocky felt the objects in his hands: a glass bulb, filled with liquid and sealed on all sides; a short metal tube with a recessed switch along one end. He slipped them into a zippered pocket and kicked away, giving the merchant a slap on the shoulder as he left. The tourist followed directly behind him.

He led the tourist through winding, indirect pathways. He waited for the tourist to question his sense of direction, to ask if he was lost. They did not.

The tourist asked him many questions.

“Are you comfortable with violence?”

“It’s normal.”

“But it seems to be, umm, everywhere. The representative told me, but I didn’t—do you ever try to stop it? Does anyone?”

“If they choose. Most don’t. Why make trouble?”

The tourist was silent for a time.

“Do you ever wish for light? Do you wish to see in the dark?”

“Stupid question.”

“Why is it stupid? The company workers, they use sensors when they enter the tunnels. Infrared. Ultraviolet. Heat maps, depth scans. You don’t see their purpose?”

“I see the purpose. We like it this way.”

There were breaks in the tunnels, wide open space. Places where the company’s machines spun and shook and swarmed, eating away at the flesh of the rock.

“Everywhere else,” the tourist said in a place of relative quiet, “people extend and augment themselves. They see and feel the virtual, the unreal-as-real. They experience broad frequencies of light and sound. Colors never seen before, sounds never heard. Here you do the opposite. You live in darkness and hear only sound that passes through thin air and solid objects.”

“That’s not a question. What is it you want to know?”

“Are you familiar with the means by which the original immigrating biosect was conceived? Substantial augmentation. The naked mole rat, of Earth’s Africa, used as a DNA template.”

Chocky bit the inside of his cheek, tasted blood.

“It is an extraordinary animal. Studied for its unique immunity to cancers. Exceptionally long-lived. Naturally able to survive in environments with low levels of oxygen, high levels of carbon dioxide. And this, a planetoid with similar conditions, containing huge deposits of radioactive ore. Extraordinary ingenuity on the part of your designers, I must admit.”

Words from the tourist. Simple words. Not short blades in the dark. Not that faint pain, something deeper. Chocky felt it, then.

“Do you know that the naked mole rat is matriarchal? That they are a hive society, like insects? Apart from a few breeding males, all other mole rats in the colony are infertile. They serve the queen as drones. By any chance, do you find anything like this behavior in your own society? Do you have a female leader, some kind of matriarch?”

Chocky tried to talk and his jaw hung open. Words cracked in his throat.

“Do you have an answer? This is the major question of my thesis. The darkness, the sounders, the violence. Your genes, perhaps. There is a connection.”

“You thought about it more than I have, spaceman.”

“Excuse me.” The tourist drifted near him, clacking and buzzing. “You seem aggravated. I hope that I have not offended you.”

“Don’t know what you mean.” Chocky whispered now. The moment demanded silence. The wound in his cheek bled profusely, filling his mouth. He swallowed it. They came to a place that was unmapped. Secret. Chocky found a touch panel and entered a code by feel. The door that they entered through hummed shut. The tunnel twisted away, and the tourist would not be able to see that it ended in bare rock past a series of sharp breaks.

“Longest trip of my life,” Chocky said. “We didn’t know if we’d survive. That’s what most don’t talk about. We waited to die for six years. And the changes, the therapy. Pain that never ended.”

“You are referring to the settlement?”

“Worth it. Worth every sacrifice. Know why?”

The tourist stopped, close and blessedly silent, for a time. “You were there. But—I assumed that you were younger.”

“Talk like that,” said Chocky, his hands shaking, “is what we wanted to get away from. Put words in someone’s head and you can control their thoughts. Images, too. You think you’re smart. All those words. But the words think for you. Keep you locked away.”

“You were human,” the tourist said. Something like fear, or awe, in its voice.

“Not human. Never. Not a fucking mole either.” He reached in his pocket and removed the glass ball. He felt the liquid swirl inside.

The tourist began a sentence with the words, “If I may,” and then Chocky smashed the glass ball against its visor. The suit’s hands leapt up to defend its passenger. It was faster than Chocky, much faster. It hit him with a burst of electricity and sent him flying.

The liquid inside the glass splattered against the suit: visor, carapace, arms, and fingers. It hissed and spat and spewed acrid smoke where it touched. The suit turned and rushed for the door, following its programming to defend its passenger, to return it to the surface in the event of any emergency. Its hands grasped the door and pulled at its useless handle, buckling the metal.

Corrosive acid ate at the suit and its visor. Chocky’s senses returned and he heard the tourist’s screams. He choked on acrid vapor that wafted from the corrosion.

The materials of the suit weakened and groaned. The suit thrashed around the enclosure, clumsy and vicious, slamming around Chocky in the dark. It tried different doors, hammered against rock with its fists.

Then the acid melted through the visor. A microscopic puncture. The suit decompressed with a pop that rang in Chocky’s ears. It kept moving, the empty shell. It moved no differently than before, with the same sense of life and purpose, but Chocky knew that the tourist was dead.

Then he pulled the short rod from his pocket and gripped it tightly. He leapt at the suit, extending the long tip of the prod. With one hand he found the hole burned in the visor, the acid cool against his skin. The suit struck him in the chest and he felt the crack of it. He plunged the prod into the visor, dug it into what was the tourist’s face, and triggered it. The suit sparked and trembled and stilled, burned from the inside out.

Chocky drifted away, his eyes full of the light of the electric flash, clutching his chest, unable to breathe. He knew the pain of broken ribs. But where the acid touched him, where it ate gaping, scorched holes in his skin, he felt no pain at all.

His shoulder knocked against a mineral crag and he held on to it, pressed himself against it. He felt the pulses: the machines of the company, all around him. There were sounders nearby, and their drums were potent.

Chocky gave the suit to a gang of salvagers and booked an elevator home to his den. He found the virgin half-dead, feral and babbling, writhing tangled in the dense netting of the room. The stink of her filled the air and made it heavy. Chocky ran his hands along the walls. Urine and excrement splattered every surface, dried and caked under his fingers.

She murmured her made-up non-language, lost in a long and lonely madness.

He kicked off and soared through the netting, hands skipping through knots and cords, a maze that he knew because it was his home. He found her by her vibrations, the thrashing motion of her. She was caught in the netting that she could never find her way through, even though it was her home, also. He found her and grabbed her, pulled her close though she fought his touch fiercely. She clawed and bit and scratched at him, ravenous and afraid. He felt her breath and her fingers and her tongue. In one hand she held a blade, dull but still cutting, and she raked it across his eyes, lips, chest. The pain of his bruised ribs was excruciating. Blood sprayed from his wounds and he heard it drip and scatter against the clutter of the den.

He felt no anger for her. He thought about the face he had seen in the tourist’s visor, that pale and ghostly thing, flesh hanging loose, a sheath of skin over bones. Small black eyes under thick folds of skin. It meant something to him, that image. It meant that she, having been made from him, may be as beautiful as he thought himself to be. It mattered, even though he had no desire to see her as she was.

It was enough to imagine the pure and holy whiteness of her skin.

He pulled the knife from her fingers and hurled it away, heard it clatter. He returned to her at last, the virgin, the mute homunculus cloned from his cells, the only joy in his life in the tunnels. She clung to him, weeping wordlessly, at last too tired to fight him. In her touch he felt her breath, her heartbeat, come into sync with his own. His life he gave to her. An unbreakable bond. Together, to the end, they would live free. The tourist’s words troubled him no more. His blood soaked them both as they hung, breathless, in the dark.

Buy the Book

The Tourist

“The Tourist” copyright © 2020 by Alex Sherman

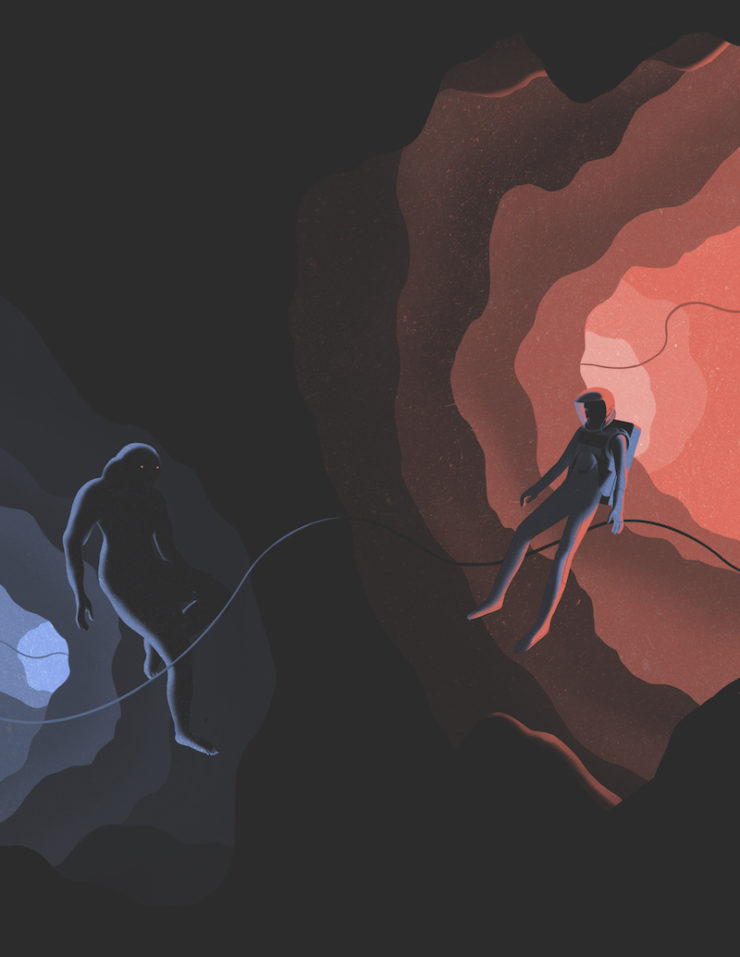

Art copyright © 2020 by Jun Cen