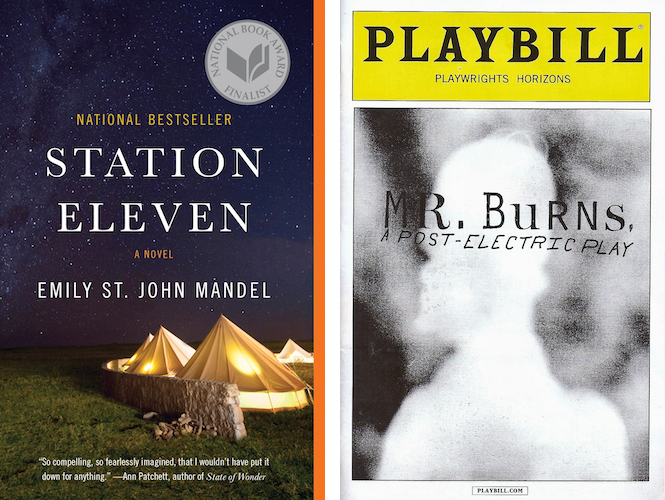

There seem to be two types of people, a friend observed to me this week: Those who have absolutely no interest in pandemic narratives at this particular point in history, and those who are strangely soothed by reading about how fictional characters respond to a world paused, and then halted, by a hypothetical disease that suddenly seems very familiar. Despite being in the latter camp, it’s not as if I take any grim satisfaction in how the early days of the Georgia Flu in Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven eerily mirror some of our current supermarket-sweeping, social-distancing status quo. Nor do I long to inhabit the post-electric world of Anne Washburn’s incredible play Mr. Burns.

Even Mandel herself has joked that people might want to wait a few months before actually reading Station Eleven, emphasizing the book’s hopeful future over our bleak present. But I would argue that now is the exact right time to get to know both the novel’s Traveling Symphony—who bring Shakespeare and classical music through post-apocalyptic towns—and Mr. Burns’ nameless theater troupe, who filter The Simpsons through oral tradition and eventually transform it into choral mythology. It’s not the pandemic that is central to either work, but rather how both tackle the aftermath. That is, the stories that the survivors tell one another in worlds that need to be lit by something other than electricity. So, what can these works tell us, as we struggle to adapt to our current crisis, about the importance of connection, memory, art, and storytelling?

Spoilers for Station Eleven and Mr. Burns, a post-electric play.

In that strange morphic resonance that characterizes certain periods of the arts, both of these works were released in the early 2010s. Perhaps both writers got to thinking about the end of the world since we had escaped the Mayans’ predicted 2012 apocalypse, though we were only a decade removed from SARS and even less from the swine flu. The first decade or so of the 2000s also marked a rise in young adult dystopian fiction, a series of thought experiments unspooling potential futures based on which cataclysmic levers got pulled in our present.

Of the two works, the Station Eleven is more widely known, by dint of being a book but especially a genre-bending book, literary fiction reflected through an unmistakably speculative lens. To wit, when we meet the Traveling Symphony in Year 20, we learn that they have emblazoned a quote from Star Trek: Voyager on one of their caravans: “Survival is insufficient,” a sentiment with which everyone can agree, even if its source material is polarizing to these aesthetes. That bit of TV trivia is more of an inside joke, as their dramatic repertoire entirely consists of the Bard’s oeuvre. Shakespeare, one Symphony member opines, is most palatable to their audiences because “[p]eople want what was best about the world.”

*

In an early draft, the Traveling Symphony performed playwrights other than Shakespeare, as well as teleplays. “But,” Mandel told Bustle around the time of the book’s publication, “I had a troupe 20 years after the end of the world performing episodes of How I Met Your Mother and Seinfeld—it may have been funny, but those are such products of our modern world. It seemed incongruous to have, in a post-electric world, these teleplays being performed.”

Mandel might have felt differently about the TV-centric approach if she had had The Civilians to do a test run. When the investigative theater company commissioned Washburn to write a play in 2008, she put a half-dozen artists in an underground bank vault to try and reconstruct a Simpsons episode without external distraction nor the temptation to Google missing details. Much of the first act is drawn verbatim from those conversations, punctuated by ums and likes and tangential ramblings.

Shakespeare might represent the world at its best, but The Simpsons is a more accurate mirror for our everyday lives. (I can count on two hands the number of actual episodes I remember, yet I’ve picked up so much about this series through osmosis from my five years on staff at Tor.com, listening to my colleagues Chris and Sarah bounce quotes and YouTube clips back and forth.) What Mandel might not have considered is that TV has always driven water cooler conversation with a universality that theater only rarely attains. (To be fair, both stories would likely be different had they been written in a post-Hamilton world.) The Traveling Symphony carries three precious, battered copies collecting Shakespeare’s works; the Simpsons survivors hold it all in their heads.

The first act of the play feels closer to Boccaccio’s The Decameron, one of the classics getting lots of play on Twitter lately, because its storytellers are closer to their plague than the Traveling Symphony is to the Georgia Flu. Lit only by a campfire, a handful of strangers struggle to piece together the plot of the 1993 Simpsons episode “Cape Feare”—itself spoofing the 1991 Hollywood remake Cape Fear. Between them they can’t even reconstruct the entire episode, and they often wind up inserting quotes from other episodes, yet the ritual provides a strange comfort.

When a stranger stumbles into their camp, the survivors greet him with a strange ritual that has developed in the weeks following a nationwide nuclear power plant collapse: Everyone pulls out a notebook and reads aloud the names of the people most important to them, hoping that this newcomer might have encountered any of them. He has not. Like the Georgia Flu, this combination of an unnamed pandemic and the resulting electric grid failure seems to have claimed the majority of the global population.

Then the stranger, who has been listening to their exquisite corpse of a Simpsons episode, comes through with the punchline nobody could remember—and suddenly he’s part of their new family.

*

Kirsten Raymonde, the Symphony member who has the Star Trek quote tattooed on her body and also embodies Titania, Queen of the Fairies, nevertheless loves another piece of pop culture above all: Station Eleven, the eponymous graphic novel about a planet-sized station that left Earth behind long ago. In all of her travels to new towns and raiding of abandoned houses, Kirsten never encounters another person who has heard of this comic, to the point where she would almost think she had made the whole thing up, if she didn’t possess a treasured print copy. While it’s not unlikely that someone in the post-apocalypse would have this same experience of being the only one to remember an obscure pop culture artifact, in Kirsten’s case it’s the truth: There exist only twenty copies total of Station Eleven, and a roundabout series of events happened to put two of them into her hands the night that the world ended.

Like any young child exposed to a pivotal piece of pop culture, and like any adult starved of other entertainment, Kirsten imbues Station Eleven with meaning far beyond its intended purpose, reading into every caption and metaphor. To be fair, there is something eerily prescient about how its creator, Miranda Carroll, somehow predicted, through the inhabitants of the Undersea, the exact longing that people in Year 20 would have for a world lost to them. But Miranda also never intends for anyone to see Station Eleven, beyond herself and her one-time husband, actor Arthur Leander. For Miranda, it was enough to simply create the world.

While Kirsten never connects the dots between Miranda and Arthur, he becomes her second cultural touchstone thanks to their brief interactions when she was a child actress in the play during which he suffered a fatal heart attack. In the decades following, Kirsten collects every scrap of information she can about Arthur, mostly in the form of gossip magazines: paparazzi shots of his unhappy marriages, rumors about his latest affairs, bloviating quotes from the man who simultaneously doesn’t want to be noticed and intensely craves the spotlight. Already famous before his death, Arthur becomes a near-mythological figure to her, a stand-in for the lost parents whose faces she cannot remember.

*

Emily St. John Mandel is to Station Eleven the book as Miranda Carroll is to Station Eleven the comic. Just as Miranda unerringly captured the grief of people in Year 20, so did Mandel describe almost six years ago the kinds of scenes taking place just last week. Jeevan Chaudhary, a man whose life crosses with Arthur as paparazzo, journalist, and paramedic, combines every possible reaction to a pandemic: Despite his worries about being seen as alarmist and overreacting, he clears out a supermarket, hoarding six shopping carts’ worth of supplies for himself and his wheelchair-using brother Frank. It’s a selfish act that is nonetheless motivated by love, and which allows Jeevan to survive and become something of a doctor in the post-electric world.

But before that, Jeevan spends weeks holed up in his brother’s apartment, watching the world end while Frank stubbornly finishes a ghostwriting project despite the fact that its subject is probably dead. The interlude brings to mind a recent well-meaning tweet that went viral for the opposite of its intended effect. While the writer meant to encourage folks to treat this self-isolation as a period of creative inspiration, drawing a line from the Bard himself to everyone sheltering at home, she didn’t account for the complete emotional and creative paralysis of not knowing how long we will have to self-isolate:

Just a reminder that when Shakespeare was quarantined because of the plague, he wrote King Lear.

— rosanne cash (@rosannecash) March 14, 2020

The Shakespeare play that Kirsten performs in the night that the world ends? King Lear. (How did she know?!)

Jeevan’s brother’s obsession with completing his project is a one-off moment, one person’s emotional response to an impossible situation. We don’t know if a tweet like this would have landed so badly in Mandel’s world, because social media conveniently winks out almost immediately. There are no strangers shaming one another for either failing to optimize their quarantine or for disappearing into their work out of comfort and/or financial necessity. Station Eleven’s survival is found in getting away, instead of staying in place. Even the Symphony’s business is transitory, trading their artistic offerings for supplies and knowledge.

The capitalist critique you might be looking for is found instead in Act 2 of Mr. Burns. Seven years after that first group of amateurs imitated Mr. Burns’ trademark “eeexcellent” around a campfire, they have become a post-apocalyptic theater company bringing “Cape Feare” and other episodes to eager “viewers,” complete with recreations of TV commercials that speak to the yearning for old-world comforts like bubble baths and Pret a Manger sandwiches.

Yet what they have (and which Mandel’s Symphony remains free of) are competitors. Other troupes—the Reruns, the Thursday Nights—cottoned on to this lucrative retelling-TV business, and have laid claim to other fan-favorite episodes. On top of that, our company operates a booth through which they invite strangers to come and contribute their memories of one-liners, the best and most accurate remembrances rewarded with vital supplies. It makes sense that even the average person would want to monetize their memory, yet there too exists the friction of people accusing the troupe of stealing their lines or not fairly compensating them.

Recreating television is a dangerous business, bound by an uneasy truce that nonetheless is severed by a shocking act of violence. Even in a post-electric world, capitalism is brutal, and takes lives.

*

While Year 20 possesses its own everyday hazards, and many of its survivors have inked evidence of the necessary kills they’ve made, Station Eleven’s violence can be traced back to a single person: the prophet.

Though they do not interact for most of Station Eleven, Kirsten has a shadow-self in Tyler, Arthur’s son and eventual cult leader. Both are about eight when the Georgia Flu erases their future, and both cope by imprinting on the nearest pieces of entertainment they happen to share: Station Eleven, and Arthur’s celebrity life. But while Kirsten’s mythologizing is harmless, Tyler misconstrues these elements drastically out of context and reforms them into a dangerous story he tells himself to justify his own survival.

Unlike the play’s Simpsons survivors, every disparate piece only further warps the narrative: Reading from the Bible, specifically the Book of Revelation, gives young Tyler the language to place the dead into the column of they must have deserved this fate, and himself and his mother into we survived, ergo we are good. Spending two years living at an airport with several dozen other passengers who know exactly who he is likely exposes him to less-than-flattering stories about his father jumping from wife to wife—behavior that metastasizes into adult Tyler’s entitlement to as many young wives as he pleases. Elizabeth’s decision to leave the Severn City airport with her impressionable child and join a cult provide him with the framework to eventually start his own following.

A key factor here is memory—and, tied up in that, the issue of class. Instantly orphaned, Kirsten and her older brother immediately begin walking; she blocks out her memory of that first year on the road and what they had to do to survive. Tyler and his mother can afford to shelter in place at an airport—sequestering themselves further in the first-class section of one of the airplanes. “The more you remember,” Kirsten reflects, “the more you lost.” She comes to Station Eleven as a blank slate, he as a sponge, which accounts for their radically different interpretations. Tucked into Tyler’s Bible is just one splash page, in which Dr. Eleven is instructed to lead following the death of his mentor. Whereas Kirsten winds up begging for her life on her knees facing the prophet’s rifle, quoting the pleas of the Undersea: We long only to go home. We dream of sunlight, we dream of walking on Earth. We long only for the world we were born into.

*

“We are all grieving our lives as they once were,” as culture writer Anne Helen Petersen recently summed up our current state. While the BuzzFeed News writer has been reporting diligently on all angles of COVID-related self-isolation—from how to talk to Boomer parents to teen coronavirus diaries—she has also maintained her own free Substack newsletter, which contains this call to action: “It’s already clear that those lives will not return as they once were: there will be no all-clear signal, no magical reversion to 2019 day-to-day-life. What happens over the next few months will affect how we think of work, and domestic division of labor, friendship, and intimacy. Like all calamities, it has the potential to force us to reprioritize, well, everything: what are needs and what are wants, what is actually necessary and what is performative, whose work we undervalue and whose leadership is actually bluster.”

Petersen’s “the collected ahp” newsletter is just one voice describing our times, one artifact of this era. There are new, quarantine-specific podcasts cropping up every day with familiar voices reiterating messages of hope. Twitter sees celebrities failing (the “Imagine” singalong) and succeeding (Tom Hanks’ dad-like encouragement) in emphasizing the importance of staying home and not spreading the disease. Theaters that were forced to close productions have made some plays available via streaming services or have mobilized their artists to write shortform, short-turnaround monologues to be put into the mouths of beloved actors. If you can believe it, watching these pieces performed over Zoom conjures up not all of the magic of live theater, but enough energy to feel electric.

Kirsten and Jeevan didn’t have Substack. The folks gathered around the fire didn’t have Instagram Stories. Yet what are these newsletters and podcasts and monologues but people taking their spots next to the digital fire and taking their turn at explaining, in their own words, what’s going on?

Neighbors in Italy serenade one another on balconies, and in Brooklyn on brownstone stoops. Food writers pivot to cooking advice columns. The Bon Appétit Test Kitchen stars become one-person camera crews in their own kitchens. Boutique fitness studios are dancing through remote cardio workouts over YouTube and Instagram. Award-winning playwrights are leading live writing classes over Facebook and Zoom. TV and movie masterclasses have dropped their paywalls so anyone can learn the secrets to creation—if they want to. What Mandel was not able to predict was the extent to which the real-time digital connection of social media would shape our experience of a pandemic.

While Mr. Burns also does away with social media, it jumps far enough ahead into the future (75 years) to postulate a similar coming-together of artistic forms. In an incredible mashup of pop hits, choral odes, fight choreography, and religious mantras, “Cape Feare” is hollowed out of almost all of its canonical plot and one-liners, instead becoming the framework for this particular population’s myth of survival. While the character of Mr. Burns was not that episode’s villain, he becomes the radioactive devil of this morality play, representing the collapse of a capitalist system that recreated what was basically Springfield’s worst-case scenario: the nuclear power plants all fail, and the survivors must deal with the fallout. They will never know a world that’s not decaying.

*

For years, I was convinced that the final visual in Station Eleven is a man on a bicycle, slowly pedaling the light back into a dark room. It seemed a whimsical demonstration of the endurance of the human spirit. Imagine my surprise, then, upon rereading and coming upon the man on a stationary bike in the first third of the novel—his exertions only managing to briefly power a laptop that still cannot log back on to the Internet. As futile as his efforts seem, Kirsten feels herself even more ineffectual, as she cannot even remember what the Internet looked like.

The book does end with a hopeful tease of electricity—an impossibly lit-up town, glimpsed through a telescope from an air traffic control tower. Someone, in the distance, has managed to bring electricity, or something like it, back. But that triumphant final note actually belongs to Mr. Burns: Act 3’s choral tradition culminates in a twinkling spectacle of Christmas tree lights, electric menorahs, chandeliers, and good old-fashioned theater lights. As a curtain falls away, it is revealed that the actor playing Mr. Burns slipped offstage after his death scene and took up his role in the crew, walking on a treadmill to power this electric display for the audience’s benefit.

Memory is a funny thing.

*

Anne Helen Petersen wraps up her newsletter by saying that “I hope we start thinking now about what we want that world on the other side to look like—what sort of protections, and safety nets, and leadership you want in place—and let every day of anger and frustration and fear bolster that resolve for change.”

Kirsten witnesses the electricity and ventures out to discover the answer behind this post-post-electric world. The Simpsons actors make that stage magic, and usher their audience back into the light.

Both the Traveling Symphony and the Simpsons survivors are forced into their rediscoveries of art—necessary reactions to their respective worlds crumbling around them. They don’t reawaken until after something has put their society, their culture, to sleep. One of the Symphony’s members, known only as the clarinet, even rails against the company’s Shakespeare snobbery. Yes, both the Bard and the Symphony live in plague-ridden worlds without the benefit of electricity, she agrees… but only one of them also lived through an electric world, and knows what they miss. Shakespeare may be timeless, but there is also room for the art that is more of their time.

We are finding our own ways into art, into (re)connection, now. We have the benefit of foresight, of nightmare futures glimpsed but not created. Make no mistake, this era is still devastating for so many, and will permanently change how much of our culture works. But for now, we can still keep the lights on, and look forward, thinking about the future we want to shape, and how to bring it into being.

Natalie Zutter really regrets being too broke to see that NYC production of Mr. Burns, but she will make it to a performance someday. Talk post-electric futures with her on Twitter!