For decades, Disney executives never bothered with sequels, apart from the occasional follow-up to an unusual project (The Three Caballeros, which if not exactly a sequel, was meant to follow up Saludos Amigos), or cartoon short (the Winnie the Pooh cartoons in the 1960s.) But in the late 1980s, struggling for ideas that could squeak by the hostile eye of then-chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg, animators proposed creating a full length animated sequel to the studio’s only real success from the 1970s—The Rescuers.

The result, The Rescuers Down Under, provided an opportunity for Disney to test out its new CAPS software, and if not exactly a box office blockbuster, did at least earn back its costs. And it happened to coincide with a sudden growth in the VCR market, along with cheaply made, direct-to-video films. The combination gave Disney executives an idea: cheap, direct to video sequels of their most popular films that could also be shown on their broadcast and cable networks.

The first venture, the 1994 The Return of Jafar, a sequel to the 1992 Aladdin, may have been a critical failure (and “may” may not be the correct word here) but small children liked it enough to make it a financial success. Joe Roth, who had replaced Katzenberg as the chairman of Walt Disney Studios, ordered more sequels for their popular animated films. The box office success of Toy Story immediately placed it in that “popular” category.

Meanwhile, over on the Pixar side, executives and computer programmers alike, bogged down by A Bug’s Life, had doubts about their current technological ability to animate either one of their other two potential projects: a little story about monsters, which required animating fur, and an even more complex idea about fish, which required animating water—something A Bug’s Life was even then demonstrating was beyond Pixar’s current animation and rendering capabilities. They worried about moving forward on either option. A fast, cheap, sequel to Toy Story, everyone agreed, would give Pixar enough time to finish A Bug’s Life, figure out how to animate fur and water, and allow Pixar to train new directors for feature films. John Lasseter started working on story concepts.

Sure, both Disney and Pixar had questions—should the sequel be computer animated, or outsourced to the cheaper hand animators then working on Disney’s TV shows and the other animated sequels? Could Pixar get Tom Hanks, who had followed up his voice work in Toy Story with yet another Oscar nomination (his fourth) for his performance in Saving Private Ryan, for a direct-to-video sequel (most people thought no) or even Tim Allen, still extremely busy with the popular Home Improvement? (Allegedly, ABC initially thought no, whatever its parent company felt.) Could Pixar afford to pay either one? (Steve Jobs thought no.) Could Pixar finally obtain rights to other popular toys, now that Toy Story was a success? (Mattel thought yes.)

The question nobody asked: what if the sequel turned out to be, well, good?

Some of these questions were immediately answered by Steve Jobs, who took a look at a few of Pixar’s balance sheets and, after agreeing with analysts that the CD-ROM game based on Toy Story would not generate as much money as a cheap direct-to-video sequel, shut down the game development and moved all of its team over to Toy Story 2. That ensured that the sequel would, like the original, be entirely computer animated. And by March 1997, to everyone’s relief, both Tim Allen and Tom Hanks had agreed to sign on for the sequel, although original producer Ralph Guggenheim soon took off (reportedly at Disney’s request) for Electronic Arts.

A few months later, Pixar and Disney realized they had two problems: (1) as it turned out, Pixar was incapable of putting together a low budget, direct-to-video film, especially while simultaneously trying to churn out a film about bugs and compose a few sketches of monsters, and (2) Toy Story 2 was turning out to be just too good for a direct-to-video production. After more meetings, in 1998 Steve Jobs announced that Toy Story 2 would be a theatrical production—a decision that also freed up money to continue to attract and keep animators who might otherwise be tempted to meander off to Katzenberg’s new venture, Dreamworks.

The decision to turn Toy Story 2 into a theatrical release also meant that Pixar had to add another twelve to fifteen minutes to the finished film. That is why, if you were wondering, Toy Story 2 opens with a scene showing a Buzz Lightyear video game—it was an easy way to add a couple more minutes to the opening and a few more lines and jokes that could be inserted later on. The final chase scene was extended, and Lasseter and the other story contributors and screenwriters added in additional jokes and scenes.

Along with needing to add several more minutes of film, Pixar animators faced a new challenge: learning how to animate dust—something achieved in the old hand animated days by either never animating dust at all (the preferred Warner Bros approach) or by filming actual dirt, echoing the use of painted cornflakes to look like snow. Achieving the dust effect took weeks of failed effort, before finally one animator animated a single fleck of dust and had the computer copy the images. And in one horrifying moment, Pixar almost lost two years of work from their internal servers; luckily, someone had backups of most—not all—of the material.

Despite all of these technical challenges, Disney refused to change the film’s release date of November 24, 1999. To be fair, that date was the perfect time to release the intended direct to video sequel, right at the height of the Christmas shopping season—but considerably less ideal for a film that now was longer and more intricate. As a result, nearly everyone involved in Toy Story 2 began putting in massive amounts of overtime and pulling all nighters. Some animators developed carpal tunnel syndrome, and one stressed animator allegedly left his baby in the backseat of his car instead of at his planned destination—daycare.

At least one animator claimed that the stress was worth it: it had, after all, produced Toy Story 2, at that point, arguably the best film Pixar had yet produced, and one of the greatest animated films of all time.

Toy Story 2 does need a few scenes to get its pacing together. It opens on a scene of Buzz Lightyear heading to take out Emperor Zurg, in a setup for a subplot and later major gag midway through the film, then spends a few moments introducing us again to all of Andy’s toys plus one new addition: Mrs. Potato Head, briefly introduced via dialogue in the previous film, but speaking in this film for the first time. Woody is preparing for a major trip to Cowboy Camp, where finally he will have Quality Time with Andy. I’m not entirely sure why Woody is looking forward to this: Andy seems like the kinda kid who is kinda rough on his toys. We’ve seen plenty of scenes where Andy throws Woody around and knocks him against things, and that’s even forgetting about the last film, where it seemed that Buzz was about to replace Woody in Andy’s affections. Plus, Woody being Woody, he’s worried—very worried—about what will happen to the rest of considerably less responsible toys while he’s gone. On the other hand, it’s his chance to have something he desperately wants: time alone with Andy.

Unfortunately for Woody, he’s in a film that, already struggling with the dust issue, for technical reasons, did not particularly want to spend any more time than it absolutely had to animating humans, and thus needed to separate him from Andy. And so, just minutes into the film, Woody faces a major tragedy: his arm is ripped, and therefore, he can’t go to Cowboy Camp.

This is not actually the sad part.

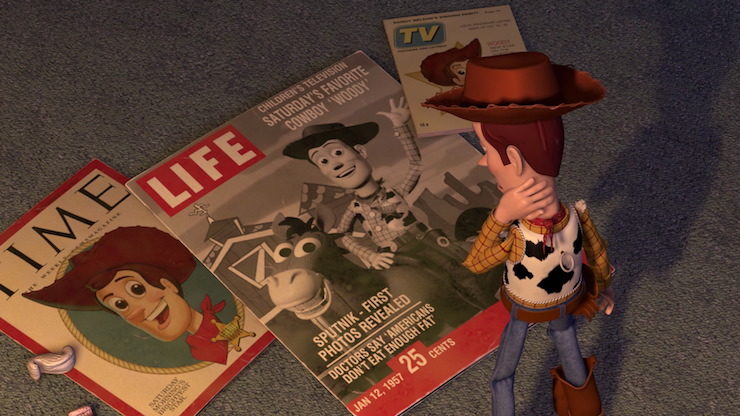

Thanks to this, and a regrettable incident when a perfectly good penguin who isn’t ready to leave Andy just yet ends up at a garage sale, leading to a series of unfortun—wait, wrong franchise. Never mind—Woody finds himself stolen by a toy collector, Al (voiced by Wayne Knight, here more or less playing his character Newman from Seinfeld), and taken to Al’s apartment. Here, Woody meets a new set of toys—notably Jessie the Cowgirl, Bullseye the horse, and Stinky Pete, the still in the box, mint quality doll—who tell him the truth: he’s one of several toys based on Woody’s Roundup, an old black and white television show from the 1940s and 1950s that bears a remarkable and hilarious resemblance to the old Howdy Doody show. The central toy from that show, as it happens.

Now that Woody has joined them, the Woody’s Roundup toys can all be sold to a museum in Japan, doomed to spend the rest of their lives separated from children by thick glass. Ok, that sounds dreadful, but for Jessie, Bullseye and Stinky Pete, it’s better than the alternative: going back into a box and into storage, unable to even see children again. Anything is better than this. Plus, Jessie no longer trusts children. She had a child once, and then… she didn’t.

All she had was a place in a donation box.

What do you do, Toy Story 2 asks, when your original reason to live and find joy in life vanishes? When you lose your best friend? When you are abandoned, or at least feel abandoned? This might seem like deep questions to ask small children, but that’s also a group that can readily understand this. Small children can and do face huge changes on a regular basis—in some cases, all the seemingly larger because they’ve had such limited experience with change. What happens to Woody and Jessie and Stinky Pete feels real because it is real: the feeling of getting hurt, the feeling of being replaced, the feeling of losing a friend.

To its credit, Toy Story 2 doesn’t provide a simple answer to this—or even one answer. Left behind on a shelf with no chance to ever play with a child, Stinky Pete sets his hopes on life in a museum, which at least means a long life, if nothing else. Jessie, convinced that losing someone that you love is far worse than never having that person in the first place, is more easily persuaded. After all, as a toy, Jessie’s ability to control her circumstances is somewhat limited (if a bit less limited than typical toys, who in general are unable to climb out of an airplane’s cargo compartment and leap to the runway). But Woody and Buzz have different thoughts. They have a child. They have Andy. And that, argues Buzz, is the most important thing for a toy.

Toy Story 2 also asks questions about loyalty, responsibility, and sacrifice. If Woody returns to Andy and his friends, he dooms the Woody’s Roundup toys to a life locked inside dark boxes. (Or so everyone claims. Watching it now, I couldn’t help but notice that not one toy suggested that just maybe they should try to look for another Woody. Sure, Al claimed that he’d spent years looking for a Woody without finding one, but as it turns out, Al thinks that just driving across a street is a major commute, so maybe we shouldn’t be taking Al’s word here, toys! You just saw how many Buzz Lightyears a manufacturer can make! Go find Woody!) On the other hand, staying with the Woody’s Roundup toys means leaving his friends—and losing his last years with Andy.

Unless—maybe—Woody can persuade the other Woody’s Roundup toys to join him.

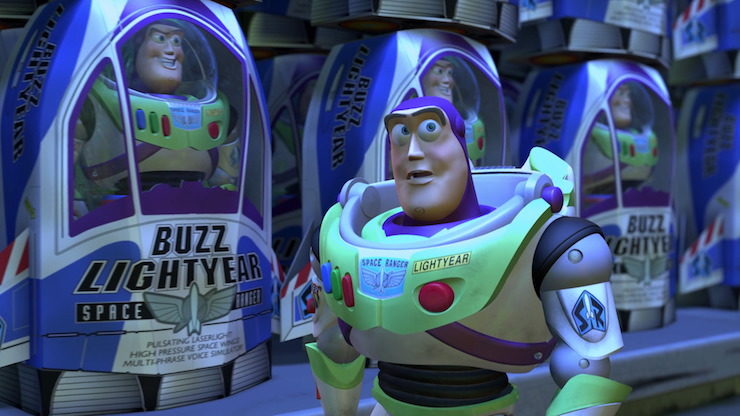

Toy Story 2 cleverly intercuts the angst ridden scenes of abandonment and fear with something much more fun: scenes of toys trying to cross a road and navigate a toy store. It’s difficult to choose any single highlight here, between Barbie’s expert mimicking of a Disney ride (in English and Spanish!); Rex finally figuring out how to win the Buzz Lightyear video game; Buzz Lightyear confronting an entire aisle of identical Buzz Lightyears, in one of the greatest images from the film; the toys failing to realize that they’ve been joined by a different Buzz Lightyear; or the emergence of Zurg, followed by a joke that, in the unlikely event that you haven’t seen Toy Story 2 yet, I won’t spoil.

Other highlights: the way this really is a sequel, featuring not just callbacks and appearances from previous characters (the sudden appearance of the Three Eyed Aliens from the first film provides another great laugh), but continued character development for Woody and Buzz. Once again, the other characters, except very arguably Rex, get a bit shafted in the character development department, but they do get a number of great lines, not to mention a major adventure.

Still missing, however: girl power. Toy Story 2 does improve on the original here somewhat, by adding Mrs. Potato Head, Barbie, and Jessie to the very slim list of female characters from the first film—Andy’s mother, Bo Peep, and Sid’s younger sister (absent in this film). Jessie, in particular, gets significant attention, and arguably the single most emotional—well, at least, the single most sniffly—scene in the film.

And yet. The toy who sets off to rescue Wheezy the Penguin? Woody, a guy. The toys who set off to rescue Woody? Buzz Lightyear, Rex the Dinosaur, Mr. Potato Head, Hamm the piggy bank, and Slinky Dog—all guys. Who sees them off? Bo Peep and Mrs. Potato Head, who never seem to even consider coming along. Navigating the terror of the airport luggage system? All of the above, plus three Three Eyed Aliens, and Stinky Pete—again, all guys, while Jessie remains locked in a box. Only in the very end does Jessie get her action adventure moment—and even then, it’s in the context of Woody rescuing her. It’s not enough to destroy my enjoyment of the film, but in a film that came out exactly one year after Mulan, inspired in part by the desire to correct this sort of thing, it’s noticeable.

I’m also not too thrilled about Stinky Pete’s final scene, where the evil toy suffers the fate—and from his viewpoint, it’s truly suffering—of getting found by a girl, and worse, an artistic girl who will, as Barbie assures him, color his face. Stinky Pete howls. On the one hand, I get it—all the poor toy had in life prior to this was the knowledge that he was in mint, box condition. Abandoned, sure, but museum quality, something that his new child will be taking away in a few seconds. And he’s not even the only toy in the film to prefer a life that doesn’t include a child—one of the other Buzz Lightyears makes the same decision earlier in the film. At the same time, though, given that part of the point of the film is that toys are better off when they are with kids, Stinky Pete’s dismay at his fate is a little painful. You’re out of the box at last, Stinky Pete! You’ll be played with! It’s what you wanted at one point! Is the problem that—I hate to say this, but I will—your new child is a girl?

Well, a touch of misogyny would hardly be Stinky Pete’s worst trait, and he really did want that life in a museum. It’s perhaps not all that surprising that he’s howling at that loss.

Though while I’m at it, given the supposed value of the Woody’s Roundup toys and the small sizes of the four main toys, why didn’t Al arrange to have all of them put into one single box that he or a courier could take to Japan by hand, keeping a constant eye on these valuable toys for their main journey? I realize that the answer is “So Pixar could give us that luggage conveyor belt scene,” but as a character/plot motivation, that lacks something.

But admittedly, these—and the poor quality of the animated fur on the dog—are nothing more than quibbles. Toy Story 2 may have left me sniffling in parts, but it also made me laugh out loud, and its final scenes are just such enormous fun that it’s difficult to complain too much. Even for me. As critics at the time noted, it’s one of the rare sequels to beat the original—proof that Pixar was not just a one-film story.

Toy Story 2 was an enormous success, pulling in $497.4 million worldwide at the box office, at the time behind only The Lion King as the most successful animated film of all time. Critics were also delighted, turning Toy Story 2 into one of the few films on Rotten Tomatoes with a 100% approval rating, something that as of this writing has been achieved by only two other animated films: the 1940 Pinocchio and the 1995 Toy Story.

By this time, Disney had belatedly realized that yes, toys related to Toy Story could indeed be a success—a previous failure snarked on in Toy Story 2’s script—and was ready to go with a full line of merchandise and related toys, including new toys based on Zurg, Jessie, Pete, and Whizzy the Penguin. The new Toy Story rides springing up at the Disney theme parks focused on Woody’s Roundup (but in color) and the world of Buzz Lightyear and Zurg introduced in Toy Story 2. Stinky Pete, naturally, never became a particularly popular toy, but Zurg merchandise continues to sell briskly.

It was all enough to give Disney and Pixar executives a new thought: what if they did a third Toy Story movie, creating a trilogy of films? Sure, that hadn’t been done with full length animated films—yet. But Toy Story possibly had more worlds of magic and toys to explore.

Originally published in March 2017.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.