News broke last Friday about the passing of Neil Peart, the drummer, lyricist, and philosophical heart of the Canadian band Rush. His departure from the circles of our world far, far too early (he was a mere 67) has left many of us grieving in ways that celebrity deaths normally do not. There’s a kind of shockwave effect running through the fandom. And here’s the thing: the guy was extremely private (in a band known for its privacy). It’s hard to miss the man himself—none of us knew him personally. Peart himself wrote, speaking of his adoring fans, “I can’t pretend the stranger is a long-awaited friend.” But losing that secluded presence of a man who produced what he produced—that we can grieve.

But wait, what business does this tribute to a rock legend—yea, even one counted among the greatest drummers of all time—have on a site devoted primarily to science fiction and fantasy? If you’re familiar with Rush, you already know why. And if you don’t, please indulge me.

In my own life, Neil Peart’s impact rivaled Tolkien’s, particularly when it comes to landscapes of individualism, personal escapism, and unambiguous moral awareness. His fans—even his bandmates—affectionately called him “The Professor.” His bookishness, his introspective mind, his methodical artistic precision, and his proclivity for (sub)creating has endeared him to many folks of geeky persuasion. The guy was a famous and uber-private introvert, but man oh man, did he find means of expression—through his virtuoso rhythms, his written words, and the vocals of Geddy Lee. He also suffered unbearable tragedies in his life and miraculously pulled through his grief and remained prolific.

Pack up all those phantoms

Shoulder that invisible load

Keep on riding north and west

Haunting that wilderness road

Like a ghost rider

But, well, this post isn’t meant to be a biography. Just a moment of homage and reflection. Neil Peart was many things—a musician, an author, a traveler, even a biker (a self-proclaimed “ghost rider”)—but if you ask me, he was a storyteller and a thinker above all. An uncompromising individualist, he made a good hero: the sort who kept his fans at arm’s length, to say the least, as he was never comfortable with fame.

And as the de facto lyricist for the progressive rock trio, this also means the complex music of Rush does so much more than impress and entertain. It tells stories of substance. Here are a few of them, along with the albums they came from. (Remember albums, Gen Xers and Boomers?!)

From his imagination to ours…

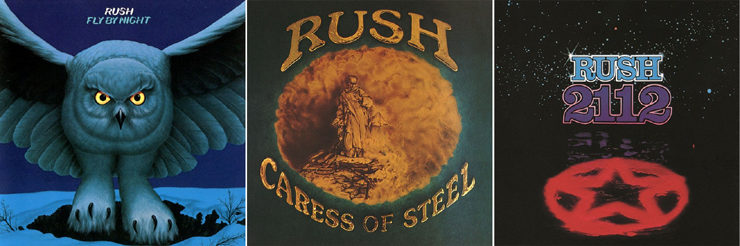

Fly By Night (1975): Rush had a self-titled first album with a different drummer, and both Alex Lifeson (guitarist) and Geddy Lee (bassist, vocalist) worked up the lyrics in that one. But in this one, Peart’s first album with the band, the song “Rivendell” is one of the finest musical paeans to Middle-earth’s famous Elven refuge. And on a personal note, this is the song that first garnered my preteen attention in the late ’80s (thanks, brother John, for bringing home that cassette!). Meanwhile, in the growling-yet-haunting showdown of bass and guitar known as “By-Tor and the Snow Dog,” we hear of the so-called Knight of Darkness (Centurion of Evil, Devil’s Prince!) set out from Hell itself to face his greatest foe, some sort of mighty… celestial?… hound.

Across the River Styx out of the lamplight

His nemesis is waiting at the gate

The Snow Dog—ermine glowing in the dampnight

Coal black eyes shimmering with hate

I’m willing to bet this was the first (and maybe last?) rock song to ever use the word “ermine.” The whole concept might seem bombastic, even goofy, but behind it Rush took nothing too seriously. By-Tor and the Snow Dog were derived from the names of some real dogs their road manager met at a party. To fans, these three guys would become as famous for their sense of humor as their musicianship. Still, the language in Fly By Night is a serious uptick in quality from Rush’s first, Peart-less album. The Professor was just still just warming up.

Caress of Steel (1975): A twenty-minute epic titled “The Fountain of Lamneth” on Rush’s third album blends Odyssean myth with what might as well be a solo D&D adventure, as an ambitious, but inexperienced young man goes in search of wonder embodied in some sort of mystical fountain; he has misadventures on the sea, meets a girl, revels and despairs, and ultimately finds weariness at the journey’s end. Then there’s “The Necromancer,” an even more Tolkienesque tale of “three travelers, men of Willow Dale,” who are preyed upon by the selfsame wizard who gazes down from his tower upon all creatures with his “magic prism eyes.”

The road is lined with peril

The air is charged with fear

The shadow of his near(ness)

Weighs like iron tears

Evil necromancer is evil! But he’s ultimately defeated by… Prince By-Tor? Totally a different person from the last album, it would seem. Or the Knight of Darkness has somehow been redeemed? The storytelling is clumsy but endearing at this point. But hey, Neil Peart was in his early 20s and still getting used to this lifestyle.

2112 (1976): On side B (remember A and B, Pre-Millennials?), there’s a straight-up homage to The Twilight Zone. But the entirety of side A from this groundbreaking album is the titular seven-part opus, inspired by Ayn Rand’s novella Anthem. (Neil would later distance himself from Rand’s philosophies, but this novella still holds up.) “2112” is set in a dystopian future among the stars, where independent thought is suppressed and “every single facet of every life is regulated“ by the domineering Priests of the Temples of Syrinx. At first, our protagonist thinks his life is good “under the atmospheric domes of the Outer Planets.” Yet one day, he discovers an ancient relic in a cave behind a waterfall, and upon learning that it’s “got wires that vibrate, and give music,” he considers what wonders what mankind might have lost, and could have again. Surely the “benevolent priests” would praise him for finding and presenting this musical device! How do you think that will go over?

Our great computers

Fill the hallowed halls

We are the Priests Of the Temples of Syrinx

All the gifts of life

Are held within our walls

Not so great, is how. The priests reject him because free-thinking, creative expression = no good for their particular status quo. They destroy what is very obviously a guitar, and the protagonist lapses into despair and experiences a potentially oracular dream. The whole thing culminates with a riotous clash as a third party arrives like an invasion to “assume control” over the existing dystopia. Good news or bad news? Neil lets us decide!

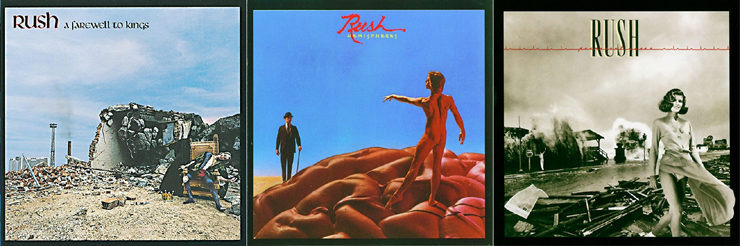

A Farewell to Kings (1977): This album is jam-packed with stories. The title track is rather political, so it’s pretty easy to substitute the “scheming demons in kingly guise” and the “ancient nobles” with whichever president or CEO best fits the bill today. Somehow the medieval imagery makes the parallel between the past and our present readily apparent, but for me it was also a fine soundtrack to my earliest D&D games. Then there’s “Xanadu,” a Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem come to life, and then some; it plays out like a cautionary tale, as the paradox of eternal life ultimately drives its seeker mad. And it’s pure fantasy.

I had heard the whispered tales of immortality

The deepest mystery

From an ancient book, I took a clue

I scaled the frozen mountain tops

Of eastern lands unknown

Time and Man alone

Searching for the lost

Xanadu

And now, a quick pause to point out that the top Billboard hit of this same year, 1977, was Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night (Gonna Be Alright).” And while the least interesting Rush songs were never quite that much of a snoozer, even their pre–Neil Peart first album had song titles like “Need Some Love” and “What You’re Doing.” That was when the band sounded like Canadian Zeppelin (and there’s nothing wrong with that), but traces of what Lee and Lifeson would become were evident.

So anyway, with that in mind, the last track of A Farewell to Kings is “Cygnus X-1,” wherein the narrator is some kind of interstellar traveler. He deliberately steers his ship, the Rocinante (you hear that, fans of The Expanse?), towards “the mysterious, invisible force” of a black hole known as Cygnus X-1.

Through the void

To be destroyed

Or is there something more

Atomized—at the core

Or through the Astral Door—

To soar…

And as Geddy Lee’s final scream sinks into the vortex of spacetime with gravitational acceleration so strong that nothing—not even light—can escape it, we’re left hanging, because the saga continues in the next album.

Hemispheres (1977): We’re six studio albums in now, and the SFF epics aren’t done just yet, as Neil Peart cherrypicks from Greek mythology (again!) in a way that would make C.S. Lewis proud (and Tolkien grumpy). The title track paints a world metaphorically “splintered into sorry hemispheres,” as the populace is swayed first towards the mind (embodied in the god Apollo) and then the heart (embodied in Dionysus).

When our weary world was young

The struggle of the ancients first began

The gods of Love and Reason

Sought alone to rule the fate of Man

Neither choice lasts, and humanity falls into strife. Yet in the midst of war, the narrator asserts himself as we’re brought back to a familiar spacecraft from the last album.

Some who did not fight

Brought tales of old to light

My Rocinante sailed by night

On her final flightTo the heart of Cygnus’ fearsome force

We set our course

Spiralled through that timeless space

To this immortal place

So it turns out flying into the center of a black hole renders one a “disembodied spirit,” bereft of form but not of awareness; and in Olympus itself he appears, where the gods are rightly amazed. They learn his story, take counsel, and decide they’ve found a solution to the world’s troubles in this erstwhile starship captain by introducing to the world a new god of balance.

With the Heart and Mind united

In a single perfect sphere

This is all very rich, of course. All these Rush opuses are mere vignettes of science fiction—and are arguably just vessels for Lee, Lifeson, and Peart’s euphonious chops—but they fire the imagination for those who give them a chance. Peart’s lyrics provide the framework of an epic story, the music powers it, and the listener can fill in the lines between the lines.

Permanent Waves (1980): This album is lush with imagery, and there are no solid stories here. Just insights. One of their well-known classics, “The Spirit of Radio,” hails from this album, an anthem to the freedom and integrity of music itself (for those who want it). No more twenty-minute songs at this point: the longest track here is the mere nine-minute “Natural Science,” which could be seen as the telescoping story of mankind itself, beginning in tidal pools and idling unaware before a QUANTUM LEAP FORWARD to more complex destinies.

The mess and the magic

Triumphant and tragic

A mechanized world, out of hand

But for all the chaos, there is order in the “wheels within wheels in a spiral array,” and eventually “the honest man” may yet “survive annihilation.”

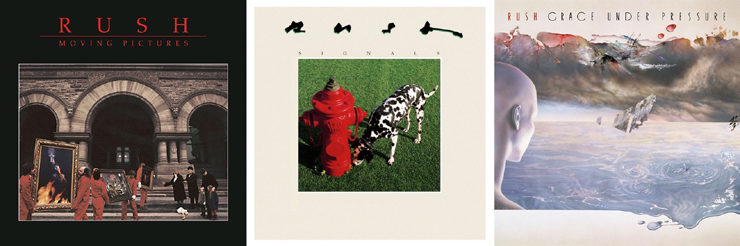

Moving Pictures (1981): Okay, so most folks have encountered “Tom Sawyer” and possibly “Limelight” a few times, but from this, Rush’s most commercially successful album, there is a lurking sci-fi yarn. “Red Barchetta,” which is ostensibly about some guy’s joy ride in the countryside, but the car in question turns out to be more than a set of vintage wheels. It’s outlawed! Neil Peart was inspired by the speculative short story “A Nice Morning Drive” by Richard S. Foster, wherein motor vehicles of the future are replaced by safer, more regulated machines. Peart’s theme of rebelling against a controlling society screeches on: when our hero encounters a monstrous “gleaming alloy-air car” on the mountain road, and then another, he whirls around with “a desperate plan.”

At the one-lane bridge

I leave the giants stranded

At the riverside

Race back to the farm

To dream with my uncle

At the fireside…

Signals (1982): As usual, every song’s got something meaningful to say, like the alienation many of us rail against as teenagers (wonderfully embodied in “Subdivisions”), or the loss of skill and vision as we grow older (“Losing It”), but I’ll cut to the chase here. The final track, “Countdown,” is Neil Peart’s love letter to human achievement, to those days “when the super-science mingles with the bright stuff of dreams.” It was inspired by the band’s in-person witness to the launching of the Space Shuttle Columbia.

Like a pillar of cloud, the smoke lingers

High in the air

In fascination—with the eyes of the world

We stare

Maybe it goes without saying that we sometimes get to look at science fiction and strip away the fiction.

Grace Under Pressure (1984): Although not quite a concept album, this one’s laden with dark, if contemplative Cold War themes (fittingly). But herein we get two sci-fi dystopias. “Red Sector A” imagines a desperate prison-camp where the narrator struggles with hope and despair; when he hears “gunfire at the prison gate” he can only wonder if it means death or liberation—poignant, since singer Geddy Lee’s parents are Holocaust survivors. In “The Body Electric,” there’s no ambiguity. The song is about a sentient machine trying to break free from the system that condemns it to a “hundred years of routines.” Only flight, and prayers to the “mother of all machines,” give our robotic hero any hope.

One humanoid escapee

One android on the run

Seeking freedom beneath

A lonely desert sun

It’s so great. But maybe avoid the video—except, y’know, for kicks—which bears less resemblance to the actual story (such are music videos) and more resemblance to, say, a low-budget Canadian Star Wars knock-off. Yet it still has some charm to it.

Incidentally, I only recently came across this illustration by painter Donato Giancola (you know, the Caravaggio of Middle-earth and frequent Tor cover artist!). This is an homage not only to “The Body Electric” but to Rush in general (notice the graffiti). I reached out to him to see if I could share it here, and he was happy to say yes. The dude’s a Rush fan, to say the least. I mean, look at this!

Guidance systems break down

A struggle to exist—

To resist

A pulse of dying power

In a clenching plastic fist…

The next phase of studio albums veer away from SFF for the most part, and the only stories are personal speculations about the real world, which at times certainly seems to be splintered into its own sorry hemispheres. (Look how polarizing ideologies are today, never mind thirty years ago!) Peart’s recurring lyrical motif, if he has one, is in resisting conformity, “swimming against the stream”—and doing so honestly, not merely for spite.

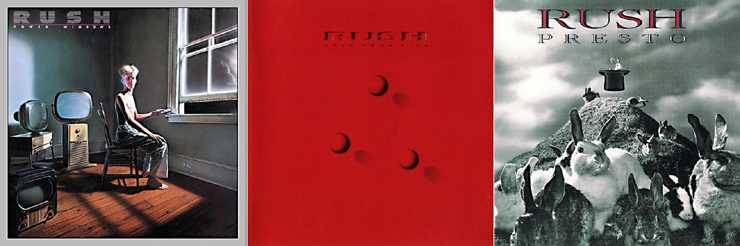

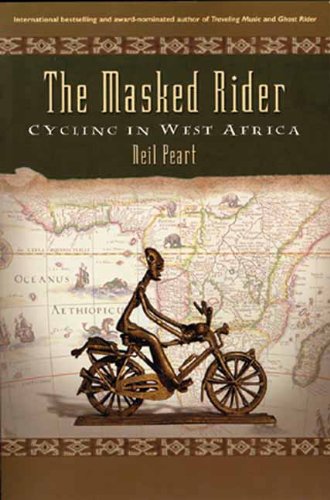

Power Windows (1985): This album reflects on the development of nuclear weapons, global territorialism, and mysteries of the unknown. Peart was clearly aware of humanity’s destructive inclinations, but seemed to maintain a sense of meliorism, anyway—even after the multiple tragedies he would later experience. And that reminds me of something else I always appreciated about Neil Peart. He wasn’t the least bit religious, was understandably critical of organized theism, but… he never claimed to have the better answers. In his first book, The Masked Rider, he called himself a “linear-thinking agnostic,” and I find that jibes with all these lyrics forever burned into my mind. I didn’t share all of the beliefs (or unbeliefs) held by my hero, but that never fazed me. I respected the man and felt less alone thanks to his words.

I think it was when I first really listened to “Mystic Rhythms” for the first time that my fandom was carved in stone. The lyrics draw no conclusions, just delight in the mysteries of the natural world, where “nature seems to spin a supernatural way.”

So many things I think about

When I look far away

Things I know—things I wonder

Things I’d like to say

The more we think we know about

The greater the unknown

We suspend our disbelief

And we are not alone

Hold Your Fire (1987): This one shared a whole slew of ideas and observations, and the now-classic “Time Stand Still” even roped in a guest female vocalist (Aimee Mann)—unheard of but awesome! Although… newbies expecting glamor should steer clear of the video, unless you really need a good laugh. Then there’s “Mission,” which addresses the all-too-familiar topic of what we aspire to do with our lives. Some of us have the drive, or the ambition, or the vision (usually not all three), but still we compare ourselves to others, wishing we had their dreams (and they, in turn, might be wishing they had simpler lives). Still, it reminds us of something.

But dreams don’t need

To have motion

To keep their spark alive

Presto (1989): A mixed bag of goodies and topics. The title track speaks to the desire we often have of just willing things to be better. Whether in big or small ways, we sometimes want to just wave a magic wand and “make everything all right.” But to me, the most soul-wrenching track here is “The Pass,” with its conscientious treatment of teen suicide, a phenomenon that had been trending all too highly at the time. Too many kids were romanticizing death, in Peart’s view. The song became a popular one for them to play live, but honestly, the conviction captured in the studio recording gives me chills.

Someone set a bad example

Made surrender seem all right

The act of a noble warrior

Who lost the will to fightAnd now you’re trembling on a rocky ledge

Staring down into a heartless sea

Done with life on a razor’s edge

Nothings what you thought it would beNo hero in your tragedy

No daring in your escape

No salutes for your surrender

Nothing noble in your fate

Christ, what have you done?

Roll the Bones (1991): The theme is clearer here: chance and (mis)fortune! Most, if not everything, that happens might just be dumb luck. A roll of the dice. The lyric “Fate is just the weight of circumstances” is the best takeaway from the title track. Warning: it takes some real commitment (and possibly some years) for the “rap” segment of “Roll the Bones” to become good fun and not just cringe-inducing to hear. Then you’re in the clear forever. The songs “Bravado” and “Heresy,” though, take a look back at recent political events, in particular the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. In an essay, Neil Peart wrote this:

The deconstruction of the Eastern Bloc made some people happy; it made me mad. For generations those people had to line up for toilet paper, wear bad suits, drive nasty cars, and drink bug spray to get high—and it was all a mistake? A heavy price to pay for somebody else’s misguided ideology, it seems to me, and that waste of life must be the ultimate heresy.

Counterparts (1993): Partnerships are the order of the day here. Two agents in symbiosis, two halves of one whole, interconnected entities that complement one and “add to each other like a coral reef.” Comedy and tragedy, lock and key, tortoise and hare, mortar and pestle, male and female. Indeed, this album offers the closest thing Rush has to real love songs. But they’re Peart-style love songs, so they’re not frivolous, not skin-deep. They’re legit, presenting one’s romantic partner as an equal, an intrinsic part of oneself. A true counterpart. Especially romantic is “Alien Shore,” which rejects the “narrow attitudes” of the roles society tries to assign.

For you and me—Sex is not a competition

For you and me—Sex is not a job description

For you and me—We agreeYou and I, we are pressed into these solitudes

Color and culture, language and race

Just variations on a theme

Islands in a much larger stream

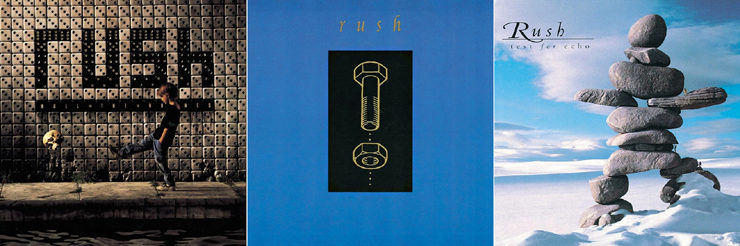

Test For Echo (1996): In the mid-to-late ’90s, the internet was rising, reality television was well underway, and Neil Peart—ever appreciating yet critical of technology—had a few remarks to make about it in this album. When the form and spectacle of technology, rather than its function, becomes our priority, we lose sight of ourselves. Are we sharing information for the betterment of all, or are we just exploiting it for base entertainment?

Don’t change that station

It’s Gangster Nation

Now crime’s in syndication on TV

Sadly, it was just after the Test For Echo tour that tragedy befell Neil Peart. In the space of ten months, he lost both his 19-year-old daughter (to a car accident) and his wife (to cancer). No one begrudged him the space and time he needed to work through the resulting agony and the emptiness, and it wasn’t clear that he would come back from it.

Rush prepared to call it quits on his account.

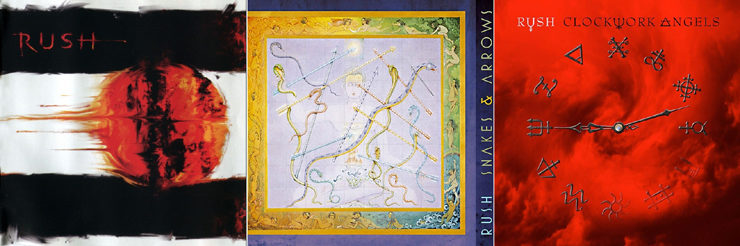

But Peart did eventually return, having ridden some 55,000 miles on a “nameless quest” through the back roads of North America, and as it turned out he had three more albums in him—not to mention tons of touring. Rush has always been a live band, delivering in person almost precisely what they offer in the studio. With Vapor Trails (2002), Peart penned “Ghost Rider” (and later a book of the same name), arguably the most autobiographical song in Rush’s discography.

Sunrise in the mirror

Lightens that invisible load

Riding on a nameless quest

Haunting that wilderness

Like a ghost rider

The subjects of Snakes & Arrows (2007) are edgier, a touch more cynical than Peart’s usual fair, rife with conflict, fear, and hypothetical angels. Guitarist Alex Lifeson’s solo acoustic instrumental, “Hope,” serves as a nice bit of counterpoint. The band has had quite a few memorable and face-meltingly awesome instrumentals, but they’re a bit off-topic here.

And this brings us to Rush’s final album, Clockwork Angels (2012), which finally brings us back to science fiction. In a big way. Hell, this is a full-blown concept album, set in a “world lit only by fire,” where alchemy and a figure called the Watchmaker imposes precision and order on the world. Steam-powered trains, steamliners, roll on in caravans toward the big cities.

In the official tour book for Rush’s 2010–2011 Time Machine Tour, Peart summed up the album’s conception:

I told the guys about an idea for a fictional world that had interested me lately, thinking it would make a great setting, maybe for a suite of songs that told a story. A genre of science fiction pioneered by certain authors (including my friend Kevin J. Anderson) had come to be called “steampunk,” seen as a reaction against the “cyberpunk” futurists, with their scenarios of dehumanized, alienated, dystopian societies.… But I was thinking of steampunk’s definition as “The future as it ought to have been,” or “The future as seen from the past”—as imagined by Jules Verne, for example in 1866, when he was writing 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

There are echoes of 2112 here, where the powers that be seem to be benevolent but ultimately try to regulate normality…and one individual resists. Craving more than the simple, predictable life that he’s been assigned in the small village of Barrel Arbor, our protagonist hops aboard one of the steamliners that roll past (“Caravan”). His destination: the capital of Crown City and Chronos Square, where the revered Clockwork Angels reside, four mechanical colossi.

Clockwork angels, spread their arms and sing

Synchronized and graceful, they move like living things

Goddesses of Light, of Sea and Sky and Land

Clockwork angels, the people raise their hands –

As if to fly

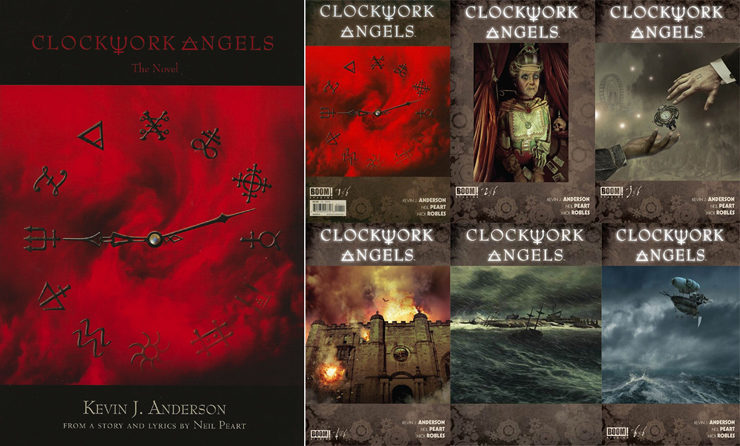

He throws in with some traveling performers (“Carnies”), falls foolishly in love (“Halo Effect”), runs afoul of a perilous agent of chaos (“The Anarchist”), and adventures beyond the sea and sky (“The Wreckers,” etc.). Based on the album’s lyrics, Kevin J. Anderson wrote a novel of the same name (the audiobook is even read by Peart!). The story he tells is an enjoyable one, though ultimately it feels like an alternate adaptation (just as Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is great, but it’s not quite the same story as in the book). BOOM! Studios even went and made a tie-in comic book series, while others cruelly teased us about a movie adaptation.

There is so much to appreciate about Rush, who changed musical styles multiple times without ever selling out, without ever compromising. There are those who like only one or two eras of the band, but I’m one of the lucky ones who loves them all and can’t even rightly pick a favorite. And oh yes, there are, of course, those who would like the band but can’t quite get past Geddy Lee’s voice. (My dad came to refer to the band as “squirrels on parade” from the many years of Rush blasting out of my room.) Say what you will, he’s got the most unique voice in rock, and it’s not always squirrely.

Some hardcore fans call them rock gods, the Holy Trinity. But that’s too much, especially for Neil Peart. Moreover, Rush has always been humble, with eyes wide open, even as they rose in accomplishment and fame beneath the mainstream. “The measure of a life is the measure of love and respect,” is one memorable line from “The Garden,” the final track of their final album, and it suits him well.

Neail Peart has left us by an ill-fated roll of the bones. Well, men are mortal. Or more succinctly, “only immortal for a limited time.” But art and expression are not, and the music of Rush is some of the best on this Earth.

But I’d like to close by emphasizing one of the things Peart excelled at: proffering hope and open-minded advice, and doing so humbly. Lately, in this political era where there seems to be a wellspring of willful ignorance and a fear of the Other, I find myself going back again and again to the song “Hand Over Fist” from Presto. It’s about resisting the impulse to fight what we don’t understand. It invites us to us to “take a walk outside” ourselves.

How can we ever agree?

Like the rest of the world

We grow farther apart

I swear you don’t listen to me

Holding my hand to my heart

Holding my fist to my racing heartTake a walk outside myself

In some exotic land

Greet a passing stranger

Feel the strength in his hand

Feel the world expandI feel my spirit resist

But I open up my fist

Lay hand over hand over

Hand over fist

It seems almost too simple. Greet a passing stranger… Neil Peart wasn’t a man who found the world and all of his insights in the pages of a book. He was a chronic traveler, and he walked the walk—or, I guess, cycled. Among his many adventures abroad, there was the time he rode a bike through West Africa, and he wrote about it in his first book, The Masked Rider. He was already rich and famous, but he was still an everyman with boots on the ground, happy to remain anonymous on a dusty, adventurous road. He went through physically rigorous travels, slept on dirty floors, and even passed through war-torn regions (how many rock stars would do that?). He experienced the world his talent and good fortune allowed him to.

Here are two short and relevant excerpts from The Masked Rider.

Cycling is a good way to travel anywhere, but especially in Africa; you are independent and mobile, and yet travel at “people speed”—fast enough to move on to another town in the cooler morning hours, but slow enough to meet the people: the old farmer at the roadside who raises his hand and says “You are welcome,” the tireless woman who offers a shy smile to a passing cyclist, the children whose laughter transcends the humblest home. The unconditional welcome to tired travelers is part of the charm, but it is also what is simply African: the villages and markets, the way people live and work, their cheerful (or at least stoic) acceptance of adversity, and their rich culture: the music, the magic, the carvings—the masks of Africa.

And…

It used to be said that electronic media would bring the world closer together, but too often the focus on the sensational only distorts the reality—drives us farther apart. That is why in Ghana the children followed me down the street chanting “Rambo! Rambo!” and that is why Canadians look at me as if I were a lunatic when I tell them I’ve been cycling in Africa—they can only picture it from wildlife documentaries, TV images of starvation camps, and old Tarzan movies.

Wise words from a nerdy white guy from Canadian has left an awfully deep, informative impression in the world for those who wish to look and listen.

Oh, and also: the man was amazing at percussion. Like, really good. You might have heard that. As Geddy often said, “Ladies and gentlemen: the Professor on the drum kit.”

By the way, it’s PEERt. Not Pert. Just sayin’.

Jeff LaSala married a female Rush fan (they absolutely do exist) and even incorporated some lyrics from Counterparts into his vows. He can’t be convinced that the fifth track from 2112 (“Tears”) isn’t somehow a magical portent of the mage Raistlin Majere (from Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance Chronicles), who didn’t show up until nine years later. When not talking about Rush, he is usually talking about Tolkien.