Sleeps With Monsters hasn’t brought you a Q&A piece in a while. But as a special winter treat, K.A. Doore (author of The Perfect Assassin and The Impossible Contract) agreed to answer some prying questions.

LB: Way back three or four years ago, when I started doing these Q&As, I would open with a question along the lines of “WOMEN!—as authors, as characters, or as fans and commenters how are they received within the SFF genre community, in your view?” These days I think it’s important to expand that question a little bit more. How do you feel women (especially queer women), and nonbinary people (or people of other marginalised genders) are received as creators, characters, and participants in the SFF field?

KD: There’s still a disparity between the way the community wants to believe we are receiving queer women and nonbinary people and their art as participants within SFF and our reality. While we’ve come a long way from open hostility, we’re still a long way from actually treating non-white, non-male, and non-straight experiences as the normal they are.

From my own relatively limited experience, there’s often a lot of people saying they want queer books or books by women or books by POC, but the follow-through is lacking. It could be the marketing needs to be better—less There Can Be Only One and more Look At All These Books! It could be the reviewers need to be more aware of what they’re saying when they say “this book is too diverse” or “this book is too much.” Or it could be that readers themselves need to actively diversify their reading lists. At some point, readers do need to take the initiative; the number of times I’ve seen someone cry into the Twitter void about not being able to find queer adult fantasy or fantasy written by women is enough to be concerning.

Thankfully, the response to those void-cries has been loud and inclusive.

But to really reach those readers who have closed themselves off to SFF because of its perceived absence of non-cis straight male writers, we as a community will have to keep doing a lot of work. There was real harm done by SFF back in the day, and even if that harm wasn’t perpetuated by most of the authors writing today, it’s still our responsibility to correct and overcome.

Real change, the kind that will persist, takes time and a whole lotta work. We’ve come a long way toward creating a more inclusive and diverse SFF community and we should absolutely celebrate that. This year alone I counted over 45 adult SFF books with at least one queer protagonist, books predominantly written by queer authors. We’ve still got a ways to go, though.

Case in point: the constant “accidental” classification of women authors as YA. But that’s another bag of worms.

LB: So, question two! Your own work so far (The Perfect Assassin, The Impossible Contract) star people with a diverse range of sexualities and gender identities and are set in a desert culture. What prompted the choice of a gay (and largely asexual but not aromantic) protagonist for The Perfect Assassin and a queer woman for The Impossible Contract? Do their sexualities matter to the narrative? Are we as a society trapped into a cycle of forever earnestly asking writers about the sexualities of queer characters as though that’s a choice that requires more (different) explanation than the sexuality of straight characters and if so, what has to change before we can start asking people to justify the inclusion of straight characters in the same way? (That’s sort of but not really a joke. Did I get meta on my own question? Sorry.)

KD: I started writing this series because I’d grown tired of reading fantasy that couldn’t imagine anything beyond the heteronormative. I specifically (and somewhat viscerally) remember the book that made me rage-write The Impossible Contract, but I’m not going to call it out because it was only one book in a long string that had the same-old “Male MC Gets with the Sole Female MC” trope. That book was the book that broke the camel’s back, so-to-speak.

I wanted to write a book that was just as fun as any other adventure fantasy, just now the adventuring girl would get the girl. I didn’t set out to play with any other tropes—I just wanted bog-standard adventure fantasy that happened to be queer. Which, almost accidentally, ended up creating a queernorm world—that is, a world where being queer wasn’t an issue. I didn’t think there was anything particularly new or transgressive about that at the time, but since then I’ve learned how rare queernorm worlds are, even in fantasy. We’re getting better—especially this year—but we’ve still got a long way to go.

So: yes, their sexualities matter, but only as much as anybody’s sexuality matters. If Amastan hadn’t been ace, hadn’t been homoromantic, his story would have been completely different. If Thana hadn’t been keen on girls, her story would have been completely different. Our queerness is a large part of our identity, it’s all twined up in our selves, but it’s just a single piece of character as anything else. But so too is a character’s heterosexuality – we have just thus far seen it as a given or baseline, instead of the piece of identity it actually is.

I look forward to the day we ask how much the MC’s hetero identity influenced their narrative. :)

LB: Next question! It’s a simple one. Why assassins? And why assassins with the particular code of ethics that the assassins of Ghadid have?

KD: The seed of the plot that would become The Impossible Contract started with a morally questionable necromancer and the assassin who kept trying (and failing) to kill him. So it was assassins from the very beginning, although it took some time for their rigid code of ethics to solidify. That was really Amastan’s doing—when he entered the story as Thana’s cousin, I had to ask myself what a level-headed, practical young man like himself was doing as an assassin. The answer, of course, was that this was a world where being an assassin was practical.

The other side of it is that I’m a gamer with roots in first-person shooters and I wanted to counteract the pervasive idea that nameless/faceless NPCs are disposable, that death doesn’t have consequences. I didn’t want to glorify murder. Which means even though every contract is carefully weighed, it’s still not morally okay. And, as in life, some of the assassins understand that, like Amastan. Some don’t.

LB: Are the assassins of Ghadid inspired by any other (fictional or otherwise) groups of assassins? And what about the water-economy worldbuilding element there? (That’s really cool, I so enjoy well-thought-out logistics.)

KD: I went pretty old-school with my assassin inspiration. I’d read up on the history of the name and the term, as you do, and was fascinated by the origin of the word, which came from a group allegedly self-styled as the Asasiyyun who were trying to establish their own independent state in Persia around 1000-1200 CE. They became infamous for murdering the leaders of their political opponents, often in crowds and broad daylight. Supposedly, they learned the language and costumes of their intended target to better blend in, and often gave their life for their cause.

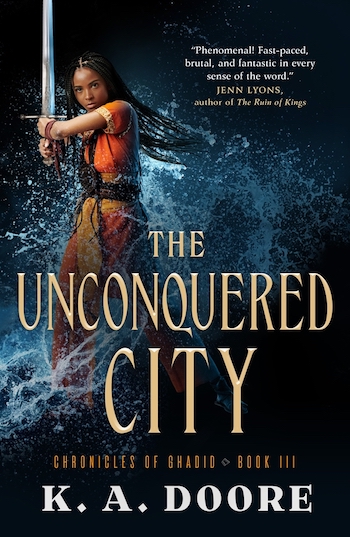

Buy the Book

The Unconquered City

I stole that idea of wholesale and committed infiltration of a mark’s home and life for the opening scene of The Impossible Contract. I then quietly sidestepped the idea of the assassin giving up their life for the contract, since that would have made for a very abbreviated story. But the idea of someone entering your home or household, becoming a part of your family, learning you better than you know yourself just to kill you and move on was seductively intriguing. That level of commitment was exactly the kind of assassin I wanted to write and explore.

As for the water-economy, that came completely from the desert I was living in at the time I wrote The Impossible Contract. The annual arrival of monsoon seasons and its violent storms and flash floods made it easy to imagine an ebb and flow to the water available to a city. With a limited supply, though, how would you make sure the water was kept safe and yet also parceled out equally throughout the year? The baat system was initially just a way to distribute water equitably; but people are people, and in Ghadid baats became currency and currency became controlled by the powerful and therefore water that should have been enough for everyone was no longer given to everyone. It was fun to play with the implications and then, later, turn that power on its head.

LB: Let’s talk about inspiration in more general terms. What writers, or what books, do you feel left a lasting impression on you? Would you say that they influence your work?

KD: Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood and For the Time Being were hugely influential on me as a writer and a human. Her lyrical and intimate stories were the first time I truly enjoyed reading literary fiction, and the first time I understood how powerful it could be. Dillard is careful about using all five senses to great effect and gives individual moments a weight that often gets lost in fast-moving, story-driven fiction. I can see her influence in the way I use details and senses to build up a more complete scene, as well as the lyrical flourishes that sometimes make it past multiple rounds of edits.

The Animorphs series by K.A. Applegate is the other single-biggest influence on me and my writing. A seemingly lighthearted and fun story about kids turning into animals and fighting an alien invasion disguised a deeper story about the sanctity of life, the brutality of war, the selfishness of corporations, the lies we tell kids, and the reality of trauma. This series really taught me the true power of fantasy: to have cool space battles, yes, but to create empathy by showing you worlds and circumstances and people you’ve never met and never imagined and expanding your own ability to imagine beyond the confines of your small world. Fantasy is deep and fantasy is powerful and fantasy is also fun and occasionally involves a tense lobster escape scene. Or, in my circumstances, a fight with an undead crocodile.

LB: What (female and nonbinary) writers working in the field right now do you think are doing really good work at the moment? What are your favourite books from the last couple of years?

KD: Oh gosh! There are the obvious—N.K. Jemisin (the Broken Earth Trilogy) has smashed through barriers for fantasy and Nnedi Okorafor (Binti, Lagoon) has done the same in science fiction—then there’s Nisi Shawl (Everfair, Writing the Other) who has been helping authors break through stereotypes and write inclusively, Alexandra Rowland (Conspiracy of Truths, Chorus of Lies) who invented and championed the hopepunk genre, Corinne Duyvis (Otherbound, On the Edge of Gone) who started #OwnVoices, and I can’t forget Malinda Lo, who has been doing an annual review of queer representation in YA fiction for the last decade and whose spotlight was absolutely integral for us getting to this golden influx of representation in all genres.

And those are just the ones off the top of my head!

Going back a few years, some of my favorite books included:

Hellspark by Janet Kagan, a linguistic mystery sci-fi from the 80s that has held up surprisingly well and is very kind and thoughtful;

The Tree of Souls by Katrina Archer, which was just such a fun and different fantasy with necromancy and time travel;

Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor, a slightly startling/disturbing sci-fi where the aliens come to Nigeria instead of NYC;

The Guns Above, and its sequel By Fire Above, by Robyn Bennis, a steampunk duology that’s good for when you just want to laugh, but also has more than enough gravitas for a serious read.

LB: So, last question—but not least: What’s coming next for you? I know the next book in the pipeline is The Unconquered City, but what are you working on for after that? What novel do you really want to write one day (or next)?

KD: Not least, but the hardest!

I have a short that will be coming out in the Silk & Steel anthology (that finished its Kickstarter at 900% funded!) later next year. Aside from that, I’ve got a WIP in the works, but no further promises except that it’s still queer af, and everything I write will continue to be so.

As for the One Day Dream, I would love to write an epic, sprawling fantasy that required massive amounts of research, indulged my inner historian & linguistics nerd, and necessitated a fancy map. It’s not just an excuse to live in the library for six months and write off some travel as well, but also it kinda is.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, was published in 2017 by Aqueduct Press. It was a finalist for the 2018 Locus Awards and was nominated for a 2018 Hugo Award in Best Related Work. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council, the Transgender Equality Network Ireland, and the Abortion Rights Campaign.