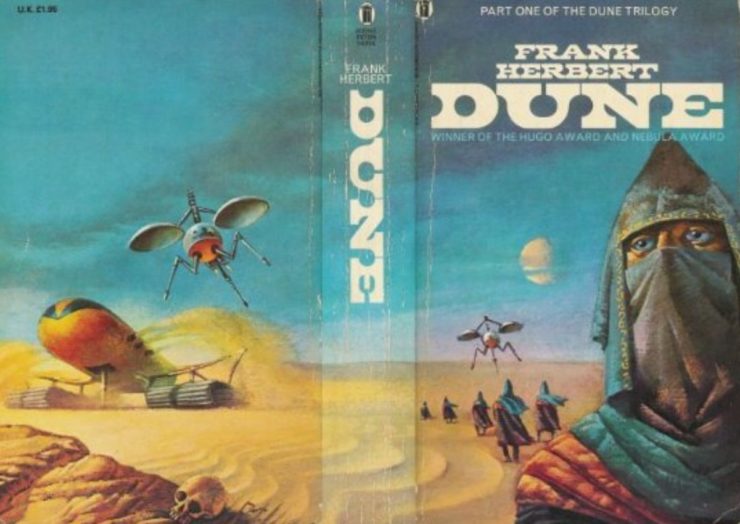

Frank Herbert’s Dune is rightfully considered a classic of science fiction. With its expansive worldbuilding, intricate politics, complex and fascinating characters, remarkably quotable dialogue, and an epic, action-packed story, it’s captured the attention of readers for over half a century. While not the first example of the space opera genre, it’s certainly one of the most well-known space operas, and indeed one of the most grand and operatic. In recent years, the novel is also gearing up for its second big-budget film adaptation, one whose cast and ambitions seem to match the vast, sweeping vistas of Arrakis, the desert planet where the story takes place. It’s safe to say that Dune has fully earned its place as one of the greatest space operas, and one of the greatest science fiction novels, ever written.

Which isn’t bad for a work of epic fantasy, all things considered.

While it might use a lot of the aesthetic and ideas found in science fiction—interstellar travel, automaton assassins, distant planets, ancestral armories of atomic bombs, and, of course, gigantic alien worms—Dune‘s greatest strength, as well as its worst kept secret, is that it’s actually a fantasy novel. From its opening pages, describing a strange religious trial taking place in an ancestral feudal castle, to its triumphant scenes of riding a giant sandworm, to the final moments featuring the deposing of a corrupt emperor and the crowning of a messianic hero, Dune spends its time using science fiction’s tropes and conventions as a sandbox in which to tell a traditional fantasy story outside of its traditional context. In doing so, it created a new way of looking at a genre that—while far from stagnant—tends to focus on relatively similar core themes and concepts, especially in its classic form (though of course there is plenty of creative variation in terms of the science, technology, and settings that characterize classic SF).

Before we dive into the specifics of Dune, we need to define what we mean by “epic fantasy.” Genre, after all, is kind of a nebulous and plastic thing (that’s kind of the point of this article) and definitions can vary from person to person, so it’s important to get everything down in concrete terms. So when I refer to epic fantasy, I’m talking the variety of high (or, if you prefer, “imaginary world”) fantasy where the scale is massive, the heroes are mythic, and the world is so well-realized there are sometimes multiple appendices on language and culture. The kind of story where a hero or heroine, usually some kind of “chosen one,” embarks on a massive globe-spanning adventure full of gods, monsters, dangerous creatures, and strange magics, eventually growing powerful enough to take on the grotesque villains and end the story much better off than where they started. There have been numerous variations on the theme, of course, from deconstructive epics like A Song of Ice and Fire to more “soft power” takes where the main character relies largely on their wits, knowledge of politics, and much more diplomatic means to dispatch their foes (The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison and Republic of Thieves by Scott Lynch do this sort of thing incredibly well), but for the purposes of this investigation, I’m going to do what Dune did and stick to the basic archetype.

Dune follows Paul Atreides, the only son of House Atreides, one of several feudal houses in a vast interstellar Empire. Due to some manipulation on his mother’s part, Paul is also possibly in line to become a messianic figure known as the Kwisatz Haderach, a powerful psionic that will hopefully unify and bring peace to the galaxy. Paul’s father Duke Leto is appointed governor of Arrakis, a vast desert planet inhabited by the insular Fremen and gigantic destructive sandworms, and home to deposits of the mysterious Spice Melange, a substance that heightens the psychic powers and perception of whoever uses it—a must for the Empire’s interstellar navigators. But what seems like a prestigious appointment is soon revealed to be a trap engineered by a multi-tiered conspiracy between the villainous House Harkonnen and several other factions within the Empire. Only Paul and his mother Lady Jessica escape alive, stranded in the vast desert outside their former home. From there, Paul must ally himself with the desert-dwelling indigenous population, harness his psychic powers, and eventually lead a rebellion to take back the planet from the Harkonnens (and possibly the Empire as a whole).

It isn’t hard to draw immediate parallels with the fantasy genre: Paul’s parents and the Fremen serve as mentor figures in various political and philosophical disciplines, the sandworms are an excellent stand-in for dragons, everyone lives in gigantic castles, and back in the 1960s, “psionics” was really just an accepted science-fictional stand-in for “magic,” with everything from telepathy to setting fires through telekinesis handwaved away through the quasi-scientific harnessing of “the powers of the mind.” The Empire’s political structure also draws fairly heavily from fantasy, favoring the feudal kingdom-centric approach of fantasy novels over the more common “federation” or “world government” approaches most science fiction tends to favor. Obvious fantasy conventions abound in the plot: the evil baron, a good nobleman who dies tragically, and Paul, the young chosen one, forced to go to ground and learn techniques from a mysterious, mystical tribe in order to survive and exact vengeance on behalf of his family—a vengeance augmented heavily by destiny, esoteric ceremonies, and “psionic” wizardry.

Buy the Book

The Last Emperox

This isn’t a simple palette swap, though. Rather than simply transposing fantasy elements into a universe with spaceships, force shields, and ancestrally held nuclear bombs, Herbert works hard to put them into a specific context in the world, with characters going into explanation of exactly how the more fantastical elements work, something more in line with the science fictional approach. It isn’t perfect, of course, but in doing things like explaining the effects and mutagenic side effects of spice, or by getting into the technical methods by which the Fremen manage to survive in the desert for long periods of time using specially-made stillsuits and other gear, or giving a brief explanation of how a mysterious torture device works, it preserves both the intricate world and also takes the book that extra mile past “space fantasy” and turns it into an odd, but entirely welcome, hybrid of an epic, operatic fantasy and a grand, planetary science fiction novel. The explanations ground the more fantastical moments of sandworm gods, spice rituals, and mysterious prophecies in a much more technical universe, and the more fantastical flourishes (the focus on humans and mechanical devices instead of computers and robots, the widespread psionics, the prominence of sword and knife fights over gunfights) add an unusual flavor to the space-opera universe, with the strengths of both genres shoring each other up in a uniquely satisfying way.

Using those elements to balance and reinforce each other allows Herbert to keep the border between the genres fluid and and makes the world of Dune so distinctive, though the technique has clearly been influential on genre fiction and movies in the decades since the novel was published. Dune is characterized above all else by its odd textures, that critical balance between science fiction and fantasy that never tips over into weird SF or outright space fantasy, the way the narrative’s Tolkienesque attention to history and culture shores up the technical descriptions of how everything works, and the way it allows for a more intricate and complex political structure than most other works in either genre. It’s not quite fully one thing, but not quite fully another, and the synergy makes it a much more interesting, endlessly fascinating work as a whole.

It’s something more authors should learn from, too. While a lot of genres and subgenres have their own tropes and rules (Neil Gaiman did a lovely job of outlining this in fairy tales with his poem “Instructions,” for example), putting those rules in a new context and remembering that the barriers between genres are a lot more permeable than they first seem can revitalize a work. It also allows authors to play with and break those rules, the way Paul’s precognitive powers show him every possible outcome but leave him “trapped by destiny,” as knowing everything that’s going to happen wrecks the concept of free will, or how deposing the Emperor leaves Paul, his friends, and his family bound by the duties of running the Empire with House Atreides forced to make decisions (like arranged marriages) based more on the political moves they have to take than anything they actually desire. In twisting and tweaking the familiar story of the Chosen One and the triumphant happy ending, Herbert drives home the ultimately tragic outcome, with Paul and his allies fighting to be free only to find themselves further ensnared by their success.

All these things—the way Dune merges the psychedelic and mystical with more technical elements, the way it seamlessly settles its more traditional epic fantasy story into a grand space opera concept, and the way it uses the sweeping world design normally found in works of fantasy to create a vaster, richer science fictional universe—are what make it such an enduring novel. By playing with the conceits of genres and inextricably blending them together, Frank Herbert created a book that people are still reading, talking about, and trying to adapt half a century after its release. It’s a strategy more authors should try, and a reminder that great things can happen when writers break with convention and ignore accepted genre distinctions. Dune is not only one of the more unusual and enduring epic fantasies ever to grace the genre of science fiction; it’s a challenge and a way forward for all the speculative fiction that follows it.

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Their writing can be found at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.