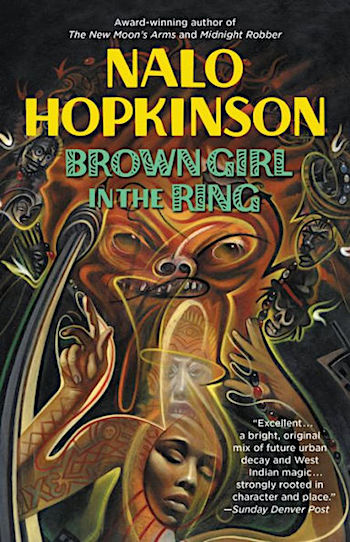

In 2016, Fantastic Stories of the Imagination published my survey “A Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction” (now hosted here). Since then, Tor.com has published 29 in-depth essays I wrote about some of the 42 works mentioned, and a thirtieth essay by LaShawn Wanak on my collection Filter House. This time we’re discussing the importance of Brown Girl in the Ring, the first published novel by the wonderful award-winner Nalo Hopkinson.

PLAYING

The act of making a piece of art can give the maker as much pleasure as those who partake of it. Daring to draw together elements as diverse as a 1957 play by Caribbean literary giant Derek Walcott, a common children’s game, and cutting-edge research on heart transplants, Nalo Hopkinson created a stunningly original world, peopled it with memorable, relatable characters, and set them moving through a simple yet involving plot. Ti-Jeanne lives in central Toronto on a repurposed model farm with her grandmother Gros-Jeanne and her nameless newborn. The town has been abandoned by its government to unscrupulous drug lords, one of whom recruits Ti-Jeanne’s ex-boyfriend to find a human heart for a high-profile transplant. Tony, Ti-Jeanne’s ex, must procure the right heart for the drug lord whether or not its donor is willing. Ti-Jeanne is front and center during Tony’s search, her own struggle with unwanted spiritual abilities becoming entangled with his darkly furtive quest. Teenaged and still attracted to Tony’s “soft brown eyes,” his sweet, tingle-inducing lips, and his “Words that promised heaven,” Ti-Jeanne struggles to escape Toronto by his side. She doesn’t exactly succeed. She does something better.

WHERE WE COULD BE STAYING

On a certain point Hopkinson’s extrapolated Toronto was spookily prescient: the abandonment of cities. Cost/benefit analysis led to the replacement of Benton Harbor, Michigan’s elected officials with a state-appointed autocrat. Detroit’s recent bankruptcy resonates with the same concerns: how long-lasting and how deeply held is politicians’ commitment to majority black urban centers? Not very deep, and not for very long, according to Hopkinson’s near-future dystopic milieu.

MAKE WAY-ING

Though Brown Girl won the Warner Aspect First Novel Contest way back in 1997, over 20 years ago, it’s still on the forefront of representation in many ways. The protagonist is a nursing mother, a rare demographic for genre heroes. And the child is an integral part of the novel’s plot, not merely a fashionable accessory.

Another major character is doubly disabled. Her mental illness and blindness originate from a curse, which some may find problematic. But she’s there, an active subject, not simply a pawn and a prop.

This book makes way for a multitude of representations of nondominant paradigms—among them, nonstandard religious practices.

PRAYING

The spiritual abilities Ti-Jeanne tries to avoid using are connected to West African traditions brought to the New World by unwilling immigrants. Hopkinson recounts Ti-Jeanne’s visions of the trickster at the crossroads, Eshu, her dances with the one-legged healer Osain, and her adventures in invisibility, all in an even-handed, non-exploitative voice. The teen’s totally plausible disaffection with a world readers will find fascinating changes over the novel’s course, and these changes make just as much sense as Ti-Jeanne’s initial cynicism.

OBEYING

Part of Ti-Jeanne’s initial reluctance arises out of a youthful desire to differentiate herself from Gros-Jeanne, who is a Vodun practitioner and follower of Osain. Part of her learned acceptance entails the realization that what she’s conforming to is not her grandmother’s idea of who she is but her own essence. In the same way, we who belong to the African diaspora sometimes see adherence to tradition and our minority community’s values as oppressive. I know I did, back in the 1960s and ‘70s, when Black Power was the One True Path per my elders as well as per my peers. I felt that hanging out with my (mainly) white friends made me special and edgy and far superior to parental control.

Now I understand obedience to traditional teaching as something other than submission to forces outside myself. I see it as akin to discipline, an act of will. It can be a form of attunement to the forces inside you, to your own heart, your own head. It can lead you away from the status quo, just as it does Ti-Jeanne.

SAYING

With this novel, in many ways, Ti-Jeanne’s creator Hopkinson also cleaves to tradition while simultaneously striking out on her own. Her father, Abdur Rahman Slade Hopkinson, was a writer too. But a poet—so though in some sense following in her father’s footsteps, Hopkinson focuses her talents in a different direction, on a slightly different task: that of telling a story. A science fiction story.

Of course, science fiction has its traditions as well. Some of these Hopkinson honors by her adherence to them, as when she sets Brown Girl in the future and posits plausible advances in technology. And some she honors by flipping or ignoring them, as with the racial makeup of her cast of characters and the tangible presence of her fictional world’s spiritual dimension.

Because she blends into it the sorts of elements some of the field’s more entrenched voices assign exclusively to fantasy, advocates of genre purity hesitate to call Brown Girl a science fiction novel. But this fussiness hinders our understanding of what is by insisting on nonexistent distinctions and labeling Hopkinson’s glorious debut based on what it is not.

What it is is beautiful. What it is is a whole world, balanced and varied. All-encompassing. Imagined, yet real. Moving, and impure and imperfect in its motion. Alive.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction, and the editor of the anthology New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction, and the editor of the anthology New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.