My teenage queer experience was chiefly one of obliviousness. I did my best to cultivate crushes on various boys, the best one of which was where I’d never met him but really admired a painting of his which had been framed in the art department. My diary from this period is tragic: “goals for this year: become friends with Sophie L. I don’t know her but she seems so nice.” I didn’t seek out queer books because I didn’t know there were any, and in any case couldn’t countenance any specific reason I would look for them. At the same time I bounced off the whole of the library’s Teen section because I “didn’t care about romance”, which I now take to mean that I wasn’t very interested in girl meeting boy.

Recollecting all this, I couldn’t help wondering whether I would have been happier and more sane if I had figured it all out sooner, and whether I wouldn’t have figured it out sooner if I’d seen myself in the mirror of fiction. I might have spent less time feeling I was missing some essential part, as if it had fallen into the sea.

It’s not like I didn’t know that gay people existed: it was 2006, civil partnership for same-sex couples had existed for two years in the UK, and I read a lot of homebrew webcomics in which sad boy vampires might eventually kiss (you may remember ‘Vampirates’). My sketchbooks were full of the same sort of thing, although I reminded myself fiercely that it was important to avoid Fetishising the Gays by thinking that there was somehow something particularly nice and pure about these scenarios. But the idea that there was mainstream fiction—let alone SFF—with queer characters—let alone queer women—never occurred to me. The few instances I stumbled across, in Neil Gaiman’s comic series The Sandman and the novels of Iain M. Banks, didn’t spark any kind of recognition. They clearly weren’t for me.

All this is to say that there will be a special place in my heart forever for the books that were for me, and that slipped queer themes past me without my realising, managing to feed my sad little heart, as it were, intravenously.

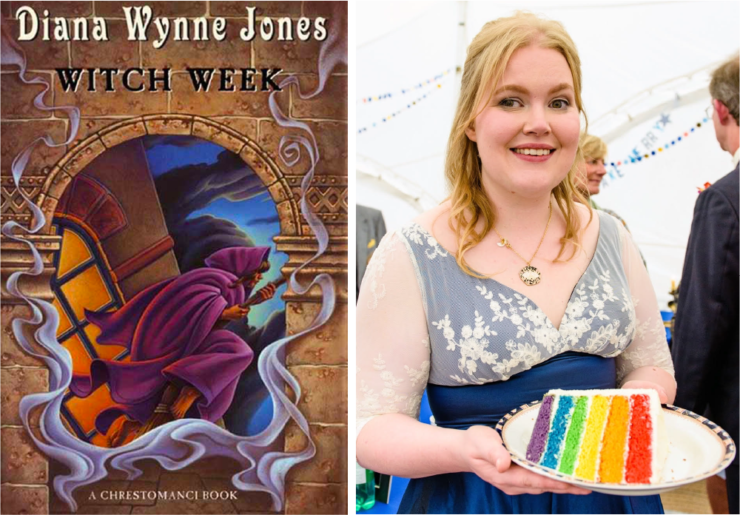

Diana Wynne Jones’ Witch Week is a novel about a remedial boarding school for witch-orphans, set in a world almost exactly like 1980s Britain except that everyone lives in fear of being arrested and burned as a witch. The story revolves around a single class of children, several of whom are suspected of witchcraft.

The casual horror of the totalitarian setting is introduced in mundane detail which disturbed me much more as an adult than when I first read it: “bone-fires” are announced on the radio; almost all the characters’ parents have been executed or imprisoned. It’s an education in the banality of evil:

His blue suit did not fit him very well, as if Inquisitor Littleton had shrunk and hardened some time after the suit was bought, into a new shape, dense with power.

We learn that witches are born with their powers and have to try to hide them, but usually can’t resist using them. One of the main characters, Charles, deliberately burns himself with a candle to try and condition himself out of doing magic. Later, a teacher discovers Charles’ secret and tries to warn him:

“You are lucky, let me tell you, boy, very lucky not to be down at the police station at this moment […] You’re to forget about witchcraft, understand? Forget about magic. Try to be normal, if you know what that means. Because I promise you that if you do it again, you will be really in trouble.”

This goes from chilling to heartbreaking when Charles later learns that the teacher is himself a witch, who has been the victim of years of blackmail:

He remembered Mr Wentworth’s hand on his shoulder, pushing him back into detention. He had thought that hand had been shaking with anger, but he realised now that it had been terror.

I’m sure you don’t need me to spell out the queer latency here, but you may be thinking that this sounds like a miserable goddamn book, a kind of middle-school V For Vendetta. DWJ does handle the grim stuff without flinching but it helps that there is a characteristically light touch—the mystery of the witches’ identity unfolds through a series of high-stakes school scrapes, where the fear of having to write lines looms larger than the fear of state violence. But more to the point, the book is genuinely uplifting. At the denouement, the mystery comes apart altogether:

Then the box beeped for Estelle too. Theresa tossed her head angrily. But Estelle sprang up beaming. “Oh good! I’m a witch! I’m a witch!” She skipped out to the front, grinning all over her face.

“Some people!” Theresa said unconvincingly.

Estelle did not care. She laughed when the box beeped loudly for Nan and Nan came thoughtfully to join her. “I think most people in the world must be witches,” Estelle whispered.

The revelation that nearly everyone in the class is a witch, that in fact nearly everyone in the world is hiding this secret self, is a moment of immense catharsis. Even the conformist bully Theresa turns out to be “a very small, third-grade sort of witch”.

The “superpower as queer identity” metaphor can break bad in all kinds of ways. (Admittedly, I’ve always loved it; I still have many lovingly coloured drawings of my X-Men self-insert character “Keziah” who had both fire and ice powers). It works here in part because magic is never actually a dark or corrupting force, but subversive, chaotic, joyful. A flock of wild birds invades the school, a pair of running shoes is transformed into a Black Forest gateau, a girl turns her school uniform into a ball gown. All of which goes to make the authorities’ disgust for magic look even more small-minded, and unjust. DWJ is a master at dissecting the hypocrisy and injustice of adults towards children, and the repression of witchcraft is given the same treatment here, not just evil but stupid and absurd:

[Charles] suddenly understood the witch’s amazement. It was because someone so ordinary, so plain stupid as Inquisitor Littleton had the power to burn him.

I can’t say that the first time I read this book I grasped any of the Themes outlined above: to me it was a blisteringly accurate description of the experience of having to go to a school and deal with other kids (bad). I read it again and again without noticing. For years I would have identified it as my favourite book by my favourite author, and yet it’s not until I reread it as an adult that I consciously put together that this book is pretty gay. The character Nan Pilgrim was always particularly dear to me: she’s lonely, bad at sports, suspicious of authority, keen on making up fantastical stories—and she forms an inseparable friendship with another girl, Estelle, who discovers Nan is a witch and reacts not with horror but with protective loyalty and kindness.

I truly have no idea whether any of this was intentional. I doubt a children’s book with more overt queer themes could have been published in 1982. An interview printed in the back of my copy quotes the author as saying “I was thinking of the way all humans, and children particularly, hate anyone who is different”, so: who knows. Regardless, I clearly got what I needed. This is a book about the triumph of nonconformity, about the misery of denying who you are and the joy of embracing it. And thank god, all this without ever spelling it out, which would have been a trial to my teenage self, who was allergic to being taught a lesson. The final message is embracing: the chances are that you are not alone in your loneliness. The irrepressible strangeness in you may be the best part of who you are:

[Nan] supposed she did need help. She really was a witch now. […] She knew she was in danger and she knew she should be terrified. But she was not. She felt happy and strong, with a happiness and strength that seemed to be welling up from deep inside her. […] It was like coming into her birthright.

Reading again this year, I was struck by the fact that the characters of Witch Week save themselves in the end by finding help from other worlds, including one where witchcraft is practised freely. Until that point, they struggle even to articulate what they are. It’s only when they learn that there is another place and another way that they’re able to imagine that things could be different, and to find purpose. Rather than only escaping to safety, they manage to transform their world. For me this is the power of both SFF and queer fiction. Lana Wachowski put it so well in the extraordinary 2012 speech in which she came out as trans: “this world that we imagine in this room might be used to gain access to other rooms, to other worlds, previously unimaginable.”

By gaining access to another world, the children are able to make their own world anew, to undo a whole history of violence, to know themselves and be free. I’m glad that the next generation have more ways to reach these other worlds where they can see themselves; I’m also glad I had this book.

A. K. Larkwood studied English at St John’s College, Cambridge. Since then, she has worked in higher education & media relations, and is now studying law. She lives in Oxford, England, with her wife and a cat. Her debut fantasy The Unspoken Name publishes February 2020 with Tor Books.