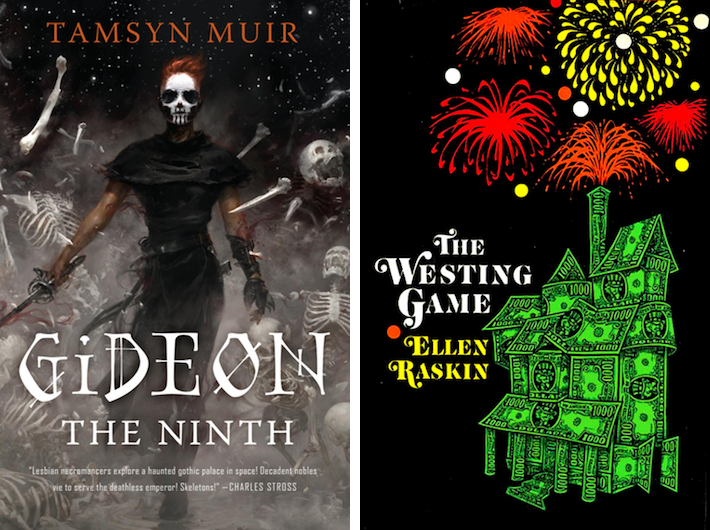

What do gooey haunted-castle space horror adventure Gideon the Ninth and The Westing Game, a children’s mystery set in an eccentric millionaire’s factory town, have in common? They both have “the” in the title!

No, but really: Despite Tamsyn Muir’s debut novel bringing to mind everything from Sweet Valley High to And Then There Were None, it bears an especial resemblance to Ellen Raskin’s 1979 classic. Both are locked-room mysteries in which sixteen relative strangers must solve a mystery that has something to do with the death and rebirth of an omnipotent man who has been pulling the strings on their entire lives. But more important than the answer is the reward—what they stand to gain from their participation. Their inheritance.

Spoilers follow for both Gideon the Ninth and The Westing Game.

I read The Westing Game with 29 other tweens in sixth grade, circa 2000. All the same age as badass fictional hall of famer Turtle Wexler, we tackled this slim mystery in a weeks-long unit that involved drawing each of the 16 heirs, playing along with them as they piece together their clues, and mock trials in which we put different characters on the stand for the murder of tycoon Samuel W. Westing. Based on who I talk to, this middle-school experience is either singular or universal, but either way, it ingrained Raskin’s quirky mystery into my mind.

When Sam Westing—equally renowned for his Westing Paper Products empire and for his penchant for dressing up as everyone from Uncle Sam to Betsy Ross every Fourth of July—dies, he leaves a two hundred million-dollar fortune… if one of his supposed heirs can identify his murderer.

These heirs, neighbors and the sole inhabitants of the luxury building Sunset Towers, are described by the omniscient (but intentionally vague) narrator as “mothers and fathers and children. A dressmaker, a secretary, an inventor, a doctor, a judge. And, oh yes, one was a bookie, one was a burglar, one was a bomber, and one was a mistake.” They are also Jewish, Greek, black, Polish, Chinese, and Chinese-American—related not by blood but by their potential fortune. That they are paired off seemingly randomly (the restaurant owner with the homemaker, the socially-awkward “freak” with the golden child) only serves to highlight their disparities in age, education, and ambition.

Similarly, when the Emperor—Necromancer Divine, King of the Nine Renewals, our Resurrector, the the Necrolord Prime—calls the heirs of eight of his nine Houses to return to the First House, each necromancer/cavalier duo defines themselves by how they are set apart from their peers. The bookish Warden and his cavalier primary couldn’t possibly have anything in common with the glittering royal twins, nor could the shadow cultists of the Locked Tomb ever level with the dreadful teens. (To be fair, they’re dreadful teens.) While Gideon Nav, who has always felt like an outcast in the Ninth House, is intrigued by these adepts with prettier clothes and sunnier personalities and foreign approaches to necromancy, Reverend Daughter Harrowhark Nonagesimus is the one who stubbornly sets them apart. This is in part to protect their secret identities as the mistake heirs, pretenders at the necromancer/cavalier relationship the other duos have had their whole lives; but as a citizen of this Empire, she comes by it honestly. Despite the fact that the Emperor had eight Lyctors (immortal warrior-saints) originally in his service, these young pairs assume that they and only they will ascend, that they must compete with the others for the secrets to Canaan House’s morbid puzzles rather than cooperate.

The Westing heirs stand to inherit not immortality exactly, but something equally transformative: money. Fortune, literal and figurative, to jump social classes, to invest in a new business or never have to work again, to write a new job title or position on a census sheet. These same impulses lead them to greedily hoard their clues—words like spacious and fruited printed on Westing Paper Towels—and spy on one another, even as a series of amateur bombings rock Sunset Towers and they begin to realize that Westing’s game may be one of revenge.

Equally myopic are the 16 House heirs stuck in a dilapidated castle full of locked rooms and abandoned necromantic experiments, unable to send out a communique nor board one of the shuttles they came in on. Even once something in the bowels of Canaan House begins to pick them off two by two, they stubbornly guard their clues out of self-centered self-preservation. Because Lyctorhood is the be-all, end-all, even if it kills them.

Each Westing heir envisions themselves as some ideal of the most deserving individual: shrewd enough to carry on a chess game with an unknown opponent, creative enough to figure out that the clues are the lyrics to “America the Beautiful,” daring enough to gamble their initial prize money in the stock market. The would-be Lyctors are no different, except that each thinks their way of approaching death and rebirth is the best, from siphoning energy out of a living battery to constructing skeleton armies to learning everything they can in a book before applying it to real life. They regard one another’s methods as juvenile or uninspired, ghastly or uncouth, assuming that there is one path to Lyctorhood instead of it being the sum of all parts.

That sixth-grade unit on The Westing Game was incomplete, however: not a moment did we spare for a discussion of the book’s wry satire of capitalism and the American Dream. Maybe because the murder mystery was complex enough for us, maybe because it was nearly a decade before the 2008 recession. Not to worry, that discourse came about almost twenty years later, via a New Yorker piece from Jia Tolentino that highlights how the book both pays tribute to American labor history while “fram[ing] America as both a land of obscure and marvellous possibility and also a hollow farce.” Every heir, from the local doctor to the kids still in high school, traces their livelihood back to Westingtown; Westing Paper Products supplies every tissue, paper cup, and disposable diaper. Samuel Westing’s very full life (and it was only one of many) was earned off the time and labor of Westingtown, even as its inhabitants fight over scraps. “Heirs, beware,” Westing’s will tries to warn, even as his heirs squabble over scraps of paper towel.

Buy the Book

Gideon the Ninth

The Empire may be spread across nine Houses and a myriad of centuries, but it is functionally the same. Worse, even, because each House was established on the foundation of being a piece of the Necrolord Prime’s figurative body: the Second House is the Emperor’s strength, the Third his mouth, the Fifth his heart, the Sixth his reason, and so forth. In turn, each House has molded itself around that particular image set forth some nine thousand years ago, leaving little room for alternate interpretations, either within its own ranks or between Houses. Even though it should be obvious that an arm is not a mouth, or that joy is not reason. The Houses are so consumed with competition that they fail to consider how much the Emperor benefits from the combined labor of his limbs.

Even before she is revealed as the mistake heir, Sydelle Pulaski takes great strains to stand out among the Westing group, faking an injury and hobbling around on crutches she repaints to match every occasion. When Turtle cruelly calls her out for her literal crutch, her seemingly perfect older sister Angela quickly turns it around into a symbolic crutch, explaining how “people are so afraid of revealing their true selves, they have to hide behind some sort of prop.” Turtle’s crutch, for instance, is her long “kite tail of a braid”—a temptation to all she passes to tug this marker of youthful naïveté, only to get a nasty kick to the shin for their presumption. But Turtle’s rage doesn’t start and end with her braid; it merely gives her an excuse to exercise the anger she already feels at the world for constantly underestimating and undermining her.

Harrow’s crutch is undeniably her bones: skeletal helpers fight her battles, pick locks, and even prop her up when she’s too exhausted from the aforementioned necromancy. She invests herself into the process, to be sure, but she has also spent her 17 years shielding herself with disposable fighters, down to her initial cavalier relationship with Gideon.

Gideon’s crutch is trickier to parse—her sword, perhaps? Not because she isn’t stunning with the rapier and absolutely stupendous with the longsword, but because the blade itself is the problem. Gideon is Harrow’s sword; it doesn’t matter which weapon she wields. It is only when Gideon makes the hardest decision for both of them, forcing Harrow to take her in instead of extend her outward, that the necromancer can achieve the Lyctorhood she once so craved and the cavalier can “really, truly, absolutely understand.” (Nope, I’m never going to be OK about this.)

This is not just the Ninth House’s problem, it’s endemic to all of the Houses. Their isolationist identities, their deeply-worn traditions and approaches, are constraints—are crutches. It would have been better if they had adopted the attitude of The Westing Game’s sweet Chris Theodorakis, initially seen only as a poor kid with a nerve disease in a wheelchair, yet able to see how fellow heirs the most clearly. When called upon to name his guess for Westing’s murderer, he instead credits the man: “He gave everybody the perfect partner to make friends.” The real secret to Lyctorhood really is the friends we made along the way? Harrow the First will learn as much in her next adventure, when she (and fellow Lyctor Ianthe, perhaps) possibly cross paths again with missing cavalier Camilla the Sixth and fake necromancer Coronabeth Tridentarius.

The secret to Samuel Westing’s longevity winds up being almost laughably simple: he lives five lives, born as Windy Windkloppel and spending varying amounts of time as magnanimous business owner Sam Westing, skeevy real estate agent Barney Northrup, humble doorman and Westing heir Sandy McSouthers, and corporate executive Julian R. Eastman. It’s not nine thousand years, but it’s more tries at the American Dream than the average citizen.

So, approaching the end of one of his lives, Sam Westing tries to share his wealth, but it can’t be as easy as a generous donation; nor does the Emperor hand out Lyctorhood like a blessing. Both require trials, and sacrifice, and self-examination. Both rewards must be earned.

Tolentino gently disagrees with Raskin’s own description of her novel as “a comedy in praise of capitalism,” instead reading it as “a comedy in praise of the messes people make when they’re allowed to access a sense of possibility.” Tabitha-Ruth (a.k.a. Turtle) Wexler becomes the only true Westing heir, guessing the key to his seemingly endless life and attaching herself, as T.R. Wexler, to the millionaire in his final decades. Harrow and Gideon grow up as well, but more than that they grow out of their dark origin stories: Harrow the living embodiment of the Ninth House’s 200 souls, Gideon the one soul that didn’t die when it was supposed to. They earn their freedom from the Ninth’s tomb, and the opportunity to revive a dying Empire, and the chance to live—well, not forever, but close enough.

Natalie Zutter (who is torn between Fifth and Sixth Houses) would love to see Gideon the Ninth taught à la The Westing Game in a sixth-grade class someday. Talk inheritance murder mysteries with her on Twitter!