The previous installment of this particular rereading took us only so far as the Botanic Gardens—but Severian and Agia hadn’t entered the Gardens yet. So, after unwittingly destroying the altar of the Pelerines, they continue on their mission to collect an avern, the deadly flower which he must use in his impending duel:

The Botanic Gardens stood on as island near the bank (of the river Gyoll), enclosed in a building of glass (a thing I had not seen before and did not know could exist).

The building seems modern in comparison with the former spaceship that is the Matachin Tower, but we must take care when using words such as “modern.” More on that in a while…

Further on in the same paragraph, Severian says something that made me laugh out loud:

I asked Agia if we would have time to see the gardens—and then, before she could reply, told her that I would see them whether there was time or not. The fact was that I had no compunction about arriving late for my death, and was beginning to have difficulty in taking seriously a combat fought with flowers.

There is humor, after all, in The Book of the New Sun. In fact, there seems to be plenty of it, carefully hidden (and sometimes not that hidden). Reading Wolfe’s essays and interviews have given me a new appreciation for the man—who seemed to be a very funny guy, even if the themes he chose to feature in most of his stories are to be taken very seriously.

Agia explains to Severian that he may do as he pleases, because the Gardens, being maintained by the Autarch, are free for all. The first thing he sees when he enters is a broad door upon which are written the words THE GARDEN OF SLEEP. An old man sitting in a corner rises to meet them: he belongs to the guild of curators. By the condition of his faded robe, and the fact that Severian had only seen two curators in his life, both old, are we to assume that everything is falling to pieces in the Autarch’s government? Indeed, things seem to be a bit run down. The curator suggests to him that he first visit the Garden of Antiquities, where they will be able to see “[h]undreds and hundreds of extinct plants, including some that have not been seen for tens of millions of years.” Instead, Severian decides to visit the Sand Garden. The curator tells him that this garden is being rebuilt, but Severian insists—he would look at the work.

They enter the garden only to find out there is no garden, just a barren expanse of sand and stone. And yet, Severian doesn’t seem to be capable of leaving the place. Agia has the answer—“everyone feels like that in these gardens sooner or later, though usually not so quickly.” And she adds, “It would be better for you if we stepped outside now.” She doesn’t seem to be affected by this spell of sorts (which puts me in mind of Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, where a group of people who gathered for a gala dinner suddenly seems unable to leave the house; the reason is never explained, though one of the characters ventures the possibility of magic). She finally convinces him to exit the place, and reveals that hours have passed, instead of minutes (the short dialogue misleads us), and they must pluck his avern and go. Severian attempts to explain his reaction to the garden:

I felt I belonged there… That I was to meet someone… and that a certain woman was there, nearby, but concealed from sight.

This will come to pass indeed, but later. They enter the Jungle Garden, where they find a hut, and inside it, a strange sight: a woman reading aloud in a corner, with a naked man crouched at her feet. By the window opposite the door, looking out, is another man, fully dressed. It becomes clear that the fully clothed man and the women (Marie and Robert) are somehow masters of the naked man, Isangoma, and that he is telling them a story that is apparently a myth of origin of his people. Although they are not (apparently) related, I was reminded of the novellas of The Fifth Head of Cerberus. In particular, Isangoma reminded me of the abos of Sainte Anne; maybe because of one sentence: “So quietly did he lean over the water he might have been a tree.” As you who’ve read Cerberus know, the aboriginals believed that some of them (or all) are children of the union between women and trees.

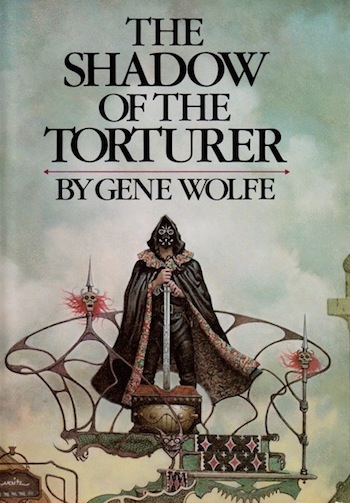

Buy the Book

The Complete Book of the New Sun

In the beginning of this particular scene, we are led to think that what is happening in front of Severian’s and Agia’s eyes is probably a kind of holographic presentation of things past—until Isangoma turns and faces them. He tells the couple that the tokoloshes (bad spirits) are there with them. Now, this moment seems reminiscent not of the Cerberus, but of The Island of Doctor Death, and the girl who tells the boy in the party that she sees him even though he may be but a dream of hers.

Isangoma explains that the tokoloshe remain until the end of the world. As might be the case. We still don’t know when Severian’s story takes place, but it most probably is at the end of history—not the end of history theorized by Francis Fukuyama in his book of that name (since then he has revised his opinions, but this is another story), but a point in the distant future where history is in a way repeating, though with other players.

Finally, Agia again convinces Severian to leave and search for the avern, and takes him to the Garden of Endless Sleep. Initially, Severian had expected to be taken to a conventional necropolis, but this garden was “a dark lake in an infinite fen.” The water, brown as tea, had:

(…) the property of preserving corpses. The bodies are weighed by forcing lead shot down their throats, then sunk here with their positions mapped so they can be fished up again later if anyone wants to look at them.

They find an old man with a boat and ask him to ferry them across the lake so that they can cut an avern. The man says he can’t oblige them because his boat is too narrow, and anyway he’s been searching for the “tomb” of his wife, whom he believes is not quite dead. He shows them a map of the corpse’s location but he swears she is not where the map points. He’s been looking for her for forty years.

Agia grows tired of this talk and hurries off in search of another boat. Severian goes after her but drops Terminus Est in the water. Without any fear for his life, he jumps in the lake to retrieve the sword. He soon finds it, wrapped in the fibrous stems of the reeds just below the surface. But he also finds something else: a human hand that pulls him down.

Here I couldn’t stop thinking of the beginning of the book, where Severian had also almost drowned, and how this first scene could be interpreted—at least by someone with a Catholic or Christian mindset—as a baptism; not an as acceptance of God, here, but symbolic of embracing a new life, of growing up. This new drowning (which again will be interrupted), brings a new person into Severian’s life—a woman who grasps him by the wrist (it is the same hand that pulls him down? Apparently not, though we can’t be sure) and helps him rise: a young woman, with streaming yellow hair. She is naked and feeling cold.

She has no memory at all. The only thing she can recall is her name—Dorcas. Agia thinks she is mad, and another man, who helped them in the lake, is sure that she has must have been assaulted, received a “crack over the head,” and that the attacker took her things and threw her in the lake thinking she was dead. He adds that people can stay a long time under the water if they are “in a com’er” (a coma, one assumes).

(The man is Hildegrin, and he also appeared in the beginning of the book, when Severian met Vodalus. He tried to kill Severian.)

They try to send Dorcas on her way, but she seems disoriented. She surprises them, saying that she’s not mad, but just feels as she had been awakened.

Hildegrin ends up taking them across the lake on his rowboat, and they finally arrive at a shore where the averns grow. Agia explains to Severian that he must be the one to pick the plant, but she guides him through the process so that he doesn’t die from the poison in the leaves. He manages to do it successfully—but the plant is huge, and carrying it is a tricky thing. Agia explains to him how to use it as a weapon, and he attempts to practice, using her advice:

The avern is not, as I had assumed, merely a viper-toothed mace. Its leaves can be detached by twisting them between the thumb and forefinger in such a way that the hand does not contact the edges or the point. The leaf is then in effect a handleless blade, envenomed and razor-sharp, ready to throw. The fighter holds the plant in his left hand by the base of the stem and plucks the lower leaves to throw with his right.

Along the way, Severian tells Agia of his love for and sadness regarding Thecla, and he suddenly reaches a very interesting conclusion:

By the use of the language of sorrow I had for the time being obliterated my sorrow —so powerful is the charm of words, which for us reduces to manageable entities all the passions that would otherwise madden and destroy us.

He is describing to some extent the logic that drives the sacrament of penance and reconciliation in the Catholic Church—that is, the confession—but he does so in a mundane fashion, not bringing religion into it, but focusing on rather a psychoanalytical explanation. (While rereading this novel, I find myself reminded of what I had already thought the first time I read this series: that Gene Wolfe might have been a die-hard, dyed-in-the-wool Catholic, but he didn’t want to proselytize. Instead, he seems to me a man who was utterly happy and content inside his religion, who merely wanted to communicate to us its joys and also its downsides. And I find myself loving him all the more for it.)

They arrive at the Inn of Lost Loves, where they will rest for a while, gathering their strength for the upcoming challenge later that day. Severian tells us that most of the places with which his life has thus far been associated were things of a distinctly permanent character, such as the Citadel or the River Gyoll. One of the exceptions is the Inn, standing at the margin of the Sanguinary Field. There is no villa around it, and the inn itself is located under a tree, with a stair of rustic wood twined up the trunk. Before the stair, a painted sign shows a weeping woman dragging a bloody sword. Abban, a very fat man wearing an apron, welcomes them, and they ask for food. He guides them up the stair, which circles the trunk, a full ten paces around.

Since the law forbids all buildings near the City Wall, the only reason they can keep an inn is because it has no walls nor roof, being in the tree, on circular and level platforms, surrounded only by pale green foliage which shut out sight and sound. Severian, Agia, and Dorcas go there, to wait for the scullion to bring them food, water, and a means to wash up. While they eat their pastries and sip wine, Severian notices that a scrap of paper, folded many times, had been put beneath the waiter’s tray in such a fashion that it could be seen only by someone sitting where he was.

Agia urges him to burn the note in the brazier without reading it. I couldn’t remember from my previous reading what this note was nor from whom, but I strongly suspected that it was from Agia or someone colluding with her. She tells him she might have some sort of supernatural power or premonition, but Severian is not that gullible, and tells her this: “I believe you still. Your voice had truth in it. Yet you are laboring to betray me in some way.”

Even believing her, he reads the note:

The woman with you has been here before. Do not trust her. Trudo says the man is a torturer. You are my mother come again.

Severian doesn’t understand it. Clearly the note wasn’t intended for him, but to one of the two women. But which one? Dorcas is very young, and Agia, though older, wouldn’t have given birth to someone who was old enough to have written the note. (Severian doesn’t know how old is she, even though, from their dialogue, we can assume more or less safely she is less than twenty-five, and Dorcas couldn’t be more than nineteen.)

Agia then urges him to go to the Sanguinary Field, because soon it will be the time for the fight—or the “mortal appointing,” as the scullion says (I must say I loved this figure of speech). Severian will go…but first, he wants to find the man called Trudo, mentioned in the note. The innkeeper tells him that his ostler (a stableboy, according to the Lexicon Urthus) is called Trudo, but when he sends for him, he finds out that Trudo has run away. They proceed on to the Sanguinary Field them, and along the way Dorcas tells Severian she loves him; Severian doesn’t seem to reciprocate (he has already made it very clear to us readers that he feels lust for Agia; that he experiences lust, not love, is significant), but before he can answer Dorcas, they hear the trumpet that signals the beginning of the monomachy ritual.

Severian is a complex character. We all know that by now, but I didn’t remember him as a person prone to violence. However, at this point of the narrative, when he asks Agia to announce him and she first refuses to do so, then ends up announcing him in a despondent fashion, he hits her; Dorcas is worried that Agia will hate him even more, and I couldn’t agree more. She will hate him, and maybe the reader will too.

After that the duel starts. They must fight right then and there, with the avern, but it still remains to be decided if they will engage as they are or naked. Dorcas interferes and asks that they fight naked, because the other man is in armor and Severian is not. The Septentrion refuses, but he removes the cuirasse and the cape, keeping the helmet because he was instructed to do so. Both Agia and Dorcas tell Severian to refuse to engage in combat, but he is young and stubborn, and he accepts. They fight, in a short but (to me, at least) believable combat scene, at the end of which Severian is mortally wounded, and he falls.

Except that he doesn’t die. Severian is allowed to get back to the fight when he recovers, but the Septentrion suddenly is afraid and tries to escape. The crowd won’t let him, and he slashes away at the people with the avern, while Agia shouts the name of her brother Agilus. Now we know who the Septentrion is, and recognize the truth of the elaborate scam.

Severian faints, and wakes up in the next day in a lazaret inside the city, with Dorcas by his side. When he asks her what happened, she explains how Agilus attacked him: “I remember seeing the leaf [of the avern], a horrible thing like a flatworm made of iron, half in your body and turning red as it drank your blood.”

Then she explains how two of the fighters finally took Agilus down after he killed several people with his avern. Severian asks Dorcas about the note. Dorcas concludes that it must have been written for her, but when Severian presses the subject, she just says she doesn’t remember.

Severian is then summoned and told that Agilus killed nine people; therefore there is no chance of a pardon for him. He will be executed—and Severian will be the carnifex, or executor. He goes to the prison to confront the treacherous siblings. Agilus explains to him that Agia initially appeared in the guise of the Septentrion, staying silent so that he wouldn’t recognize her voice. The reason for the attempted fraud? Terminus Est—the sword is worth ten times their shop, and the shop was all they had.

The two blame Severian, because he cheated death, and for several other reasons, and they attempt to beg and bully their way, trying to force Severian to free Agilus, which he does not. Agia even offers her body to him, and tries to steal coins from his sabretache. He doesn’t let her. Instead, he returns to stay with Dorcas, and they end up making love twice, but she refuses him a third time:

“You’ll need your strength tomorrow,” she said.

“Then you don’t care.”

“If we could have our way, no man would have to go roving or draw blood. But women did not make the world. All of you are torturers, one way or another.”

This last sentence made me stop reading for a while and ponder (I can’t remember if I did the same on that first reading. Maybe not; I am a different person now, as we all are, with the passing of time). All males are torturers. This is a hard pill to swallow even now, but it merits contemplation. So I will leave my readers to think about it while I end this article.

At last, the Shadow of the Torturer falls–on Agilus in the scaffold. Severian kills the man without pomp and circumstance, and that’s it. He is handsomely paid for the execution—a master’s fee—and moves on to Thrax with Dorcas, all the while asking himself why did he not die when the poison of the avern should have killed him? He tries to tell himself Agia that lied and that the poison didn’t kill him because it didn’t kill everyone. It is then that he discovers in his belongings the Claw of the Conciliator. He then concluded that Agia had stolen it and put it in his things, and that’s what she was trying to steal from him during the encounter in Agilus’s cell, not his coins.

They come upon Dr. Talos and Baldanders again, presenting a play. The two are not alone: there is a beautiful woman with them, Jolenta, who happens to be the waitress Severian met in the same inn at which he met the two men. Severian and Dorcas end up participating in the strange but elaborate play that mixes things old and new (in fact, they are all old, but by now we are used to regarding Severian’s times as purely medieval…though we should remember that that’s not the case). On the following day, they will meet another character in this story: Hethor, a stuttering man who had already met Severian the night before he executed Agilus. He seems to be a bit disconnected from reality, and talks about ships that travel in space—a thing that apparently was quite common but stopped happening centuries before Severian’s birth—so they don’t pay much attention to him.

The last character to be introduced, in the final pages of the novel, is Jonas, a rider with a cyborg arm. He immediately falls in love with Jolenta, who doesn’t appear to reciprocate. But then they approach the City Wall—and this book comes to an end.

Rereading this work and deciding what aspects to discuss became an almost impossible task, in some ways—if everything in Wolfe’s work is significant, then I should put everything in the articles. But I’m afraid that the map is not the territory. I can only touch on so much in these articles, and I don’t intend to split the rest of the books in many installments going forward; maybe two per book.

Allow me to snatch a quote from Severian himself:

But in a history, as in other things, there are necessities and necessities. I know little of literary style; but I have learned as I have progressed, and find this art not so much different from my old one as might be thought.

I am also learning as I progress in this rereading. Things will be missed, naturally; I can’t do anything about that. What I can—and I will—do is to be as faithful to my original idea as I can: to try and express my thoughts and feelings about Gene Wolfe’s work. Even though I’m an academic, I wanted simply to write here about my perceptions as I revisit these books. I hope I will still be of help to you in that respect, and hope you will share your own thoughts in the comments.

See you on October 3rd for The Claw of the Conciliator…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.