“These are the oldest memories on earth, the time codes carried in every chromosome and gene. Every step we’ve taken in our evolution is a milestone inscribed with organic memories.” —The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard

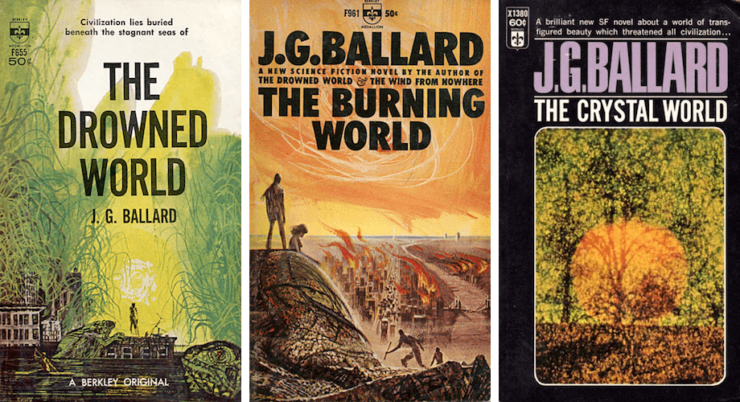

In The Drowned World (1962), Earth has flooded due to soaring temperatures, species regress to their prehistoric forms, and humanity retreats to the Arctic while being subconsciously drawn to the boiling southern seas. Surreal, bleak, and suffused with ennui, it is a novel not about death, but transformation. Writers in postwar England found high-modernist optimism didn’t speak to their reality. Their lives weren’t interrupted by a distant war, but rather were defined by it, and their literature needed to be summarily transformed to match. Inspired by avant-garde writers like William S. Burroughs, they gazed not towards the stars but to the world within, and so the New Wave was born amidst the English rubble—so named, according to some sources, by critic Judith Merrill, borrowing from the French Nouvelle Vague movement in cinema.

The field of biology, too, was poised for an unanticipated but inevitable transformation. For a hundred years, the holy grail had always been the easing of human suffering, from developing better treatments to eugenically redefining humanity. While the nightmare reality of the Nazi eugenic program killed off the latter approach, the former was revitalized by the expansive understanding of the nature of life facilitated by the molecular biology revolution of the ’50s and ’60s. As biologists followed their logical lines of inquiry away from the central dogma, the transformation would come from a rather unexpected place.

A defining voice of the British New Wave came from an equally curious place. James Graham Ballard was born in 1930 to British expats in the splendor and squalor of the international city of Shanghai. Sino-Japanese conflicts since the 19th century had caused a steady stream of Chinese refugees to pour into the wealthy port city, and Ballard grew up with his wealthy but distant parents amid extreme poverty, disease, and death. On December 7th, 1941, the Japanese seized the city, rounding up international citizens in internment camps, including Ballard’s family—giving Ballard a front seat to the capricious violence of humanity. Despite hunger, disease, and more death, Ballard wasn’t entirely unhappy, being close to his parents for the first time, but at the war’s close, upon returning to England, they abandoned him to boarding school. Ballard, who never before set foot on British soil, was struck by the dissonance between the nostalgic vision of England extolled by the expats in China with the grim reality of its grey skies, bombed out streets, and exhausted citizenry.

Back in the realm of science, genes were key in understanding genetic disease, but genes remained frustratingly inaccessible, and following a 1968 sabbatical, Stanford biochemist Paul Berg switched focus from bacterial to mammalian gene expression. Bacteria were well studied due to their ease of culture, but they were fundamentally different from higher order cells, and Berg wanted to decipher their differences. He wanted to use simian virus SV40, which infected mammalian cells and integrated its circular DNA into the host’s genome, to insert pieces of bacterial DNA and see how conserved the mechanisms were. Berg knew a number of bacterial proteins for cutting, pasting, and copying DNA were available in nearby labs, so he devised a method to stitch the SV40 virus to a bacterial virus containing the three lac operon genes and see if he could ultimately express them. Berg used six different proteins to cut and join the DNA, and by 1972 he had successfully created the first “recombinant” DNA molecule hybrid.

Ballard found himself to be a kind of hybrid upon his return—British by birth, but American in sensibilities, with a different set of wartime traumas than his classmates —he found diversions in Cambridge bookshops, magazines, and cinema where he developed an appreciation for film noir, European arthouse films, and American B movies, and the moods of alienation he found in Hemingway, Kafka, Camus, Dostoevsky, and Joyce. But it was the truths about humanity he discovered in the work of Freud and the Surrealists which inspired him to write. In 1949, he entered medical school for psychiatry, and his two years spent studying and dissecting cadavers became an exercise in taking the dictum “Physician, heal thyself” to heart, as Ballard exorcised his survivor’s guilt and humanized the death that had permeated his childhood. He decided to focus on writing and moved to London in 1951, where he worked odd jobs and struggled to find what he hoped would be a groundbreaking voice.

Recombinant DNA was groundbreaking in the creation of something new to nature, but was also as a powerful tool to interrogate individual gene function. Berg’s method yielded little product, so his graduate student, Janet Mertz, aimed to improve its efficiency. She approached Herbert Boyer, a microbiologist at the University of California San Francisco who worked on restriction enzymes—”molecular scissors” that bacteria evolved to cut invading viral DNA. Boyer had recently isolated EcoRI, which had unprecedented specificity and left “sticky” ends, which vastly improved Mertz’s reactions. To bulk up the yield further, she proposed using the replication machinery of E. coli to make copies (i.e. clones) at a 1971 seminar at Cold Spring Harbor, but encountered unexpected backlash. SV40 caused cancer in mice, but was unknown to do so in humans, and concerns about inserting potential oncogenes into a bacteria that lived in the human gut gave Berg pause. Mertz held off putting the constructs into E. coli and Berg consulted with micro- and cancer biologists. They concluded it was low risk, but Berg didn’t want to be wrong. As biochemist Erwin Chargaff put it, “You can stop splitting the atom; you can stop visiting the moon; you can stop using aerosol… but you cannot recall a new form of life.”

In 1954, Ballard needed a change in his life and joined the RAF to indulge his interest in flight and gain time to write; during training in Canada he discovered science fiction paperbacks in a bus depot. Science fiction had stagnated in the ’50s, and Ballard found much of the literature at the time, Astounding included, too earnest and self-involved, ignoring the psychological aspect of the everyday world. Instead, it was the stories of near-future extrapolations of social and political trends in Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction which gave him a sense of vitality. He demobilized, and with the support of his new wife, Mary, he sold his first stories in 1956 to the English markets Science Fantasy and New Worlds, both edited by John Carnell. Carnell believed SF needed to change in order to remain at the cutting edge, and encouraged Ballard to focus on developing his surrealist psychological tales. Furthermore, Ballard meshed his love of the emerging pop art aesthetic into his early Vermillion Sands stories, where intangible things like time and sound became fungible in the hands of the desert city’s vice-addled artist community, as he explored recurrent themes involving overpopulation, man’s relationship to time, and the dark side of the Space Age.

Still fearful of the darker implications of recombinant DNA, Berg called for design and safety measures to be established, as more and more requests came in to his lab for materials, but the Pandora’s box had been opened. Stanley Cohen, a new professor at Stanford studying plasmids (extrachromosomal circular DNA transferred when bacteria mate, carrying traits such as antibiotic resistance), organized a plasmid conference in Hawaii in 1972. He invited Boyer based on his EcoRI discovery, and one night as the two walked the beach in Waikiki they found they had the materials for a “safer” and more robust cloning method—one not involving virus-bacteria hybrids. Cohen had a plasmid that carried antibiotic resistance and was proficient in transformation, a technique to get plasmids into bacteria. With EcoRI, they could move the antibiotic resistance gene from one plasmid to another, allow it to transform, then see if the bacteria grew in the presence of the antibiotic. By 1973, after shuttling supplies up and down Highway 101, they’d cloned the first wholly bacterial recombinant DNA, demonstrating the ease and versatility of the new technique.

Buy the Book

The Future of Another Timeline

Meanwhile, the postwar economic boom and influx of baby boomer youth into London had become its own Pandora’s box, revitalizing the city and inaugurating the progressive swinging ’60s social revolution. Ballard flourished in the artistic climate, publishing further boundary-pushing stories in more markets, but his day job as assistant editor of a scientific journal ate into his writing time. To finally write full time, he needed to sell a novel to the booming book market and rushed to produce The Wind From Nowhere (1961), the first in a sequence of catastrophe novels. But it was his second novel, The Drowned World, which established Ballard as the voice of something new. His focus on “inner space,” where a character’s environment melds with their psyche, compelling them to a destructive unity with a dying world, was compelling, and he followed it up with The Burning World (1964), and The Crystal World (1966), a gorgeous surrealist masterpiece in which epidemics of crystallization threaten to consume the world.

Boyer and Cohen’s scientific masterstroke inspired John Morrow, a graduate student in Berg’s lab to replicate the experiment with frog DNA. When it worked, the resulting paper—published much to Berg’s horror behind his back—became a media sensation with its implications for synthesizing other higher order compounds, like insulin or antibiotics. Berg quickly gathered signatures from half a dozen scientists in a letter to Nature demanding a moratorium on such experiments, and organized the 1975 Asilomar conference, inviting scientists, lawyers, and journalists. Despite the excitement, public fear of genetic engineering was stoked by works like Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain and Nixon’s hostility towards science; Berg hoped that proactive self-regulation would help avoid potentially crippling government oversight. Debate was heated and resulted in a hasty set of temporary guidelines, formalized by the NIH in 1976, banning experiments like Morrow’s outside of the highest levels of biosafety containment (to which few institutions worldwide had access).

In 1964, Michael Moorcock took over New Worlds and his inaugural editorial issued a call for a new kind of science fiction, in which he celebrated William Burroughs’ portrayal of their “ad-saturated, Bomb-dominated, power-corrupted times,” along with the work of British writers like Ballard who were “revitalizing the literary mainstream.” His pronouncement caused a stir, with denouncements from Hard SF traditionalists, who held that science fiction was a genre of intellectual prediction, not a literature of emotion, and proponents on the other side arguing that naive optimism made science fiction trivial by ignoring the emotional realities of the world—realities which writers like Ballard embraced. Ballard’s fiction certainly reflected his own inner turmoil, and when his wife died suddenly from pneumonia that year, he became a single father and threw himself into fatherhood, whiskey, and writing. In 1969, he released The Atrocity Exhibition, a novel influenced by Burroughs, about a man having a psychotic breakdown while reconstructing consumerism, the assassination of JFK, the Space Race, and Marilyn Monroe’s death. Ballard further explored the overlap of atavism and the human psyche in his next three novels: probing the connection between sex and the violence of car crashes in Crash (1973), imagining a version of Robinson Crusoe stranded on a traffic island in Concrete Island (1974), and offering a meditation on human tribalism in High-Rise (1975).

In 1976, a split in the scientific community began when Boyer was approached by Robert Swanson, a venture capitalist drawn to the Silicon Valley tech scene. Excited about recombinant DNA technology, Swanson worked his way down the list of Asilomar attendees looking for someone to start a company with. Boyer’s son was deficient in human growth hormone (HGH), so he knew therapeutics like HGH were inefficiently harvested from donated cadavers and could conceivably be made using a recombinant approach. Genentech was founded that year, the world’s first biotechnology company. Swanson wanted to target low-hanging pharmaceutical fruit like HGH or insulin (which was harvested from ground-up animal pancreases, occasionally causing anaphylactic shock), but Boyer urged caution. Proof of principle experiments were needed before approaching risk-averse pharma companies for funding. First, they needed to prove that they could express a protein, and collaborated with researchers at nearby City of Hope National Medical Center to quickly clone and express the bacterial lac repressor. Next, they had to express a human protein. To get around the Asilomar restrictions on cloning higher order DNA, they chose the 14 amino acid-long protein somatostatin and used a new method to design and successfully clone synthetic DNA, encoding the protein in 1977. Boyer declared, “We played a cruel trick on Mother Nature.”

For decades, Ballard had channeled the cruel tricks of his own mind into his fiction, but as his children grew, he found himself thinking more and more about Shanghai. In 1984 he finally tackled his past head-on in the compellingly brutal and moving semi-autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun, his first best seller, which Steven Spielberg adapted in 1987. It was a Rosetta Stone for Ballard fans, revealing the traumatic origins of all the drained swimming pools, abandoned hotels, flooded rivers and deserted runways in his fiction. In his memoir, Miracles of Life (2008), the author recounted how his tackling of the topic allowed him to finally let it go, claiming the decade to follow would be some of the most contented years of his life; his fiction reflected that, with a concentration on more literary/crime stories. Ballard died from cancer in 2009, but his distinctive perspective survives and has made his name into an adjective (“Ballardian”) that captures the feeling of a bleak and modern surrealism, which at its heart was always a celebration of the miracle of life.

Back on the front lines of scientific progress, Berg argued against restricting the miracle of recombinant DNA technology at a 1977 Senate subcommittee hearing, citing the expression of somatostatin as a “scientific triumph of the first order… putting us at the threshold of new forms of medicine, industry and agriculture.” Eli Lilly, the pharma insulin giant, was struggling to meet demand and thus issued contracts to Genentech and Harvard to produce human insulin. While Harvard struggled with regulations, Genentech, a private institution, operated outside their scope and in their incorporated lab space in South San Francisco, they successfully expressed human insulin in 1978, then HGH in 1979, (a success which proved critical in 1985 when an outbreak of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease was linked to cadaver-derived HGH).

1980 was a pivotal year: the central question of the patenting of life forms was definitively answered by the Supreme Court, going against scientific traditions of open exchange of information and material, and the subsequent media frenzy began a troubling trend of prioritizing press conferences over peer review, which alienated academic biologists. With the ability to patent their technology, Genentech went public with a miraculous Wall Street debut, raising $36 million on their first day, paving the way for the foundation of new biotechs, simultaneously alienating and blurring the lines between academia and industry as scientists moved between them. Ultimately, fears over recombinant technology proved overblown and restrictions were lifted, allowing the technique to become a staple lab technique, and Berg would win the 1980 Nobel prize for his pioneering work.

Next up, we’ll dive deeper into the New Wave and examine what it means to be human by delving into the work of developmental biologist Sydney Brenner and a master of the postmodern, Philip K. Dick.

Kelly Lagor is a scientist by day and a science fiction writer by night. Her work has appeared at Tor.com and other places, and you can find her tweeting about all kinds of nonsense @klagor