Have you ever wondered just what a rabbit has to do with the resurrection of Jesus? Or what the word “Easter” really means? And, for that matter, what’s with all the eggs? Could it be, as Jon Stewart once wondered, that it’s because Jesus was allergic to eggs?

Alas, no. But how we got to all this egg and bunny business is nevertheless a cool and rather medieval story.

But before we get to the Middle Ages, there’s some earlier Christian history and theology to unpack to understand Easter’s importance and its resulting traditions. I’ll try to keep this as succinct (and objective) as I can.

Rome and Messiahs

Aside from a fringe of folks who subscribe to the Christ Myth Theory, there’s near universal scholarly consensus that a Palestinian Jew named Jesus preached in the first decades of the Common Era. The year of his birth is unclear (the Christian Gospels seem to contradict themselves on the dating), as is the year of his death. He was a charismatic figure, though. He drew crowds, and he was almost assuredly proclaimed as a Messiah by many of his followers.

Then he died.

And dying is very much not what a Messiah was supposed to do.

A Messiah (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ), you see, had a fairly specific checklist of duties according to the Bible and the Jewish traditions surrounding it during the lifetime of Jesus. Most vitally, the Messiah needed to defeat the enemies of the Jews, and, following the example of King David, re-establish a properly Jewish kingdom in Israel. I’m simplifying things a bit here, but the Top 10 List of Israel’s Enemies during the life of Jesus would have looked something like this:

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- Rome

- People who work with Rome

So kicking Rome in the tail, to say the least, was pretty much a necessary thing to do for those who claimed to be the Messiah at the time.

And, as it happens, lots of folks were claiming to be a Messiah. During the year 4 BCE, for example, there were at least four different Messiahs running through the countryside around Jerusalem. One of them, a man named Simon of Paraea, was a former slave of Herod the Great; he was tracked down by the Roman general Gratus and beheaded—a death that has been theorized to be behind the mysterious “Gabriel’s Revelation” stone. (Shameless Plug Alert: The Realms of God, the third book of my Shards of Heaven trilogy, includes part of Simon’s story.)

Needless to say, being crucified by Romans, as Jesus apparently was (or beheaded by them, as Simon was), didn’t really fit with the idea of defeating them. So, like the followers of the defeated Simon, the followers of Jesus must have decided he wasn’t the Messiah after all and trundled off to follow another leader… except, well, they didn’t.

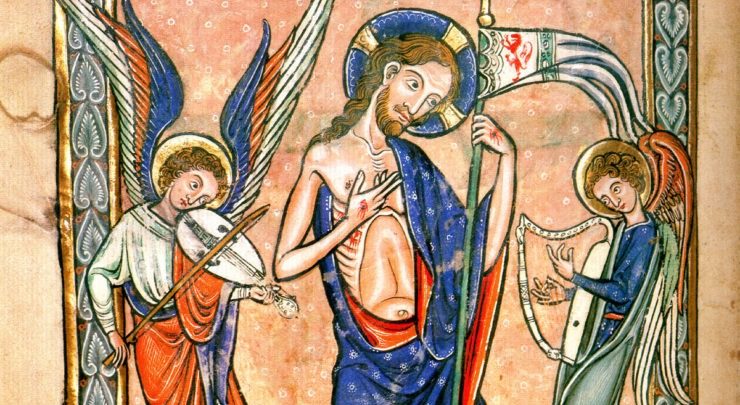

According to Christian history, the reason this particular movement didn’t dissipate is that three days after Jesus died, his followers began to claim that he had reappeared. He had been resurrected by God, and not long afterward he ascended into Heaven.

That still wasn’t what a Messiah was supposed to do—Rome was still around, after all—but it was hardly what had happened to Simon and all the other would-be Messiahs, who’d (presumably) died and stayed dead. The Resurrection was something very different, and the followers needed to figure out exactly what that something was.

In the end, through the twists and turns of a variety of fascinating thinkers (yep, I read Origen alongside Origin), Christian doctrine posited that Jesus really was the Messiah: folks just hadn’t really understood before him what a Messiah was actually supposed to do. The war the Messiah was waging wasn’t against Rome, they said, it was against Death. Jesus’ Resurrection, his followers said, had defeated Death and saved folks from everlasting torment in Hell.

So, yeah, for these believers, the Resurrection event was pretty much the biggest thing ever possible.

Even bigger than Christmas.

Dating Easter

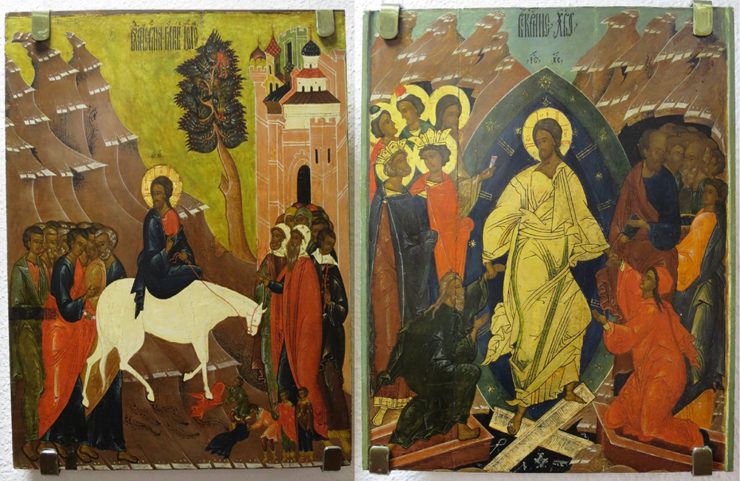

The Christian calendar, for all the above reasons, was built around the annual celebration of the Resurrection event. This was the real “New Year,” and dating it should have been easy: the Gospels were clear that Jesus died in Jerusalem during the Jewish celebration of Passover, and Passover begins on the 15th of the Hebrew month of Nisan every year, which falls on the first full moon after the vernal equinox in the northern hemisphere. Piece of cake.

Trouble is, the Jewish calendar is lunisolar (dealing with the moon and sun), whereas most folks in and around the Mediterranean used the only-solar Julian calendar. So confusion about the “correct” date started early. Even by the middle of the second century, we know from the meeting of Polycarp (bishop of Smyrna) and Anicetus (bishop of Rome) that churches in the east and west held different dates for this most important Christian celebration. Polycarp and Anicetus agreed to disagree, but as time went on it was clear that something had to be done. In the year 325 the First Council of Nicaea—where good St. Nicholas did his heretic punching!—it was decreed that the Jewish calendar was officially abandoned and that Christians would henceforth celebrate the resurrection on a Sunday. Problem solved.

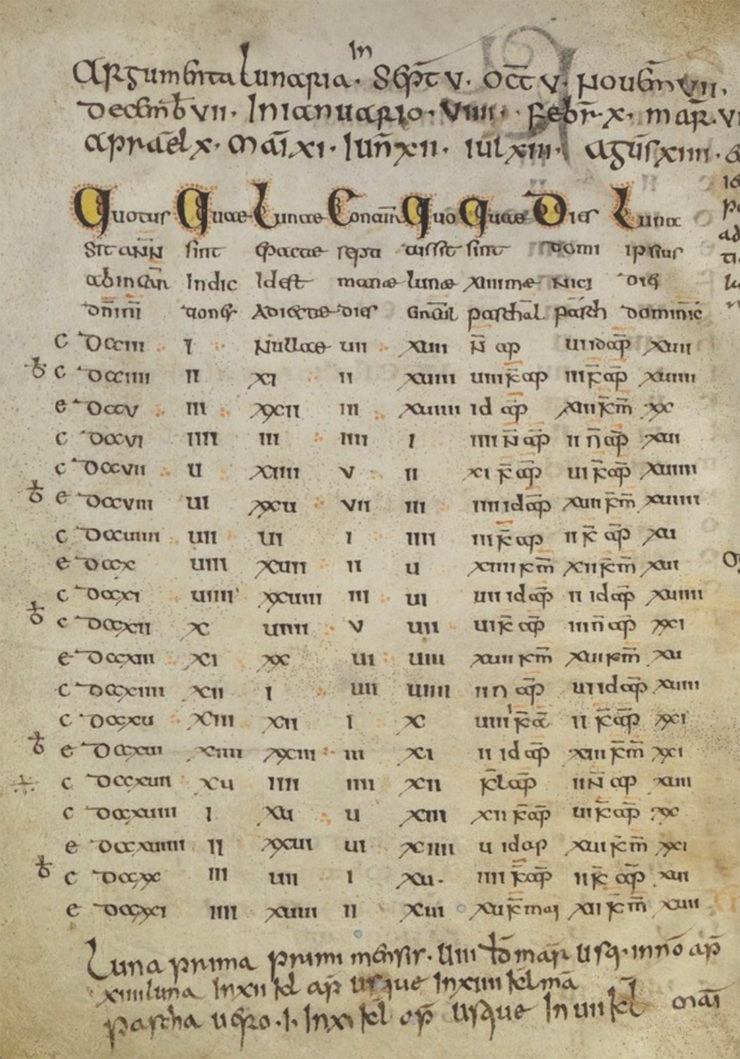

Unfortunately, this decree didn’t resolve things. Which Sunday was it? Elaborate tables were constructed to enable the correct execution of the Computus, as this most important calculation came to be known. Different calculation tables led to different solar-calendar dates for Easter.

In one memorable event, Celtic and Roman Christians running into each other in the north of England in the seventh century found that they had such different dates that the Synod of Whitby had to be called in 664 in order to resolve the issue and resolve the impasse. The decision at Whitby favored Rome, which angered the monks of Iona but at least allowed everyone to get back to work in Whitby. Good for Whitby, but folks still had different calculation tables in other places, and then the Gregorian calendar reform came in 1583 and the Catholics and most Protestants adopted it because it was easier, but not everyone did because a lot folks wanted to keep their older traditions and…

Well, it’s all still a jumble even today. In most Catholic and Protestant churches Easter is defined as the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the March equinox, which means it can fall for them any time between 22 March and 25 April on the Gregorian calendar. Most Eastern churches, though, didn’t adopt the Gregorian reforms; for them, it can fall between 4 April and 8 May.

Long story short? Don’t feel bad if you’ve no idea when Easter is next year.

(And if you want a high-res look at the Computus tables in a marvelous 12th-century medieval manuscript, check out this site!)

So about the Bunny and the Eggs…

Jews and Christians aren’t the only folks who tied a major holiday to the spring equinox. It’s pretty universal, in fact, for human cultures to take note of the cycle of increasing and decreasing periods of daylight: this is a relatively simple way to track the seasons and thus the best times to plant and to harvest. Put simply, the spring equinox set off a time of “life”, while the flip-side equinox set off a time of “death” (and thus contributed to the formation of Halloween).

It’s pretty fitting, then, that Christianity’s story of Jesus rising from the dead should be associated with the spring. Most resurrection and/or fertility deities are.

Among a long list of such figures, it’s worth it to point out one: Ēostre. She was a Germanic goddess of the dawn, bringing life back into the world after the cold death of night. The spring equinox would have been her most important festival, representing her overcoming the frigid grasp of Old Man Winter and such. Her importance to the moment led to her name being applied to the month of the equinox (“Eostur-monath,” as the Venerable Bede recorded it in his 8th-century work, The English Months). This popular pagan name survived past the conversion of the populace, so that the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection (in which the “light” of the “son/sun” conquered the “darkness” of “death/night”) came to be called, in many Germanic areas, Easter.

It seems likely, too, that Ēostre gave Easter more than its name. As a goddess bringing new life, she would have had strong connections to fertility, which could be symbolized by both eggs and rabbits (for obvious reasons).

In a parallel development, hares were also associated with the Christian story since, in the Middle Ages, it was believed that they could reproduce without losing their virginity, which associated them with the veneration of the Virgin Mary in church iconography. So the appearance of an Easter Bunny, a kind of springtime Santa that brought eggs to good boys and girls, was probably inevitable. (It’s first attested, just so you know, in 1682 in the writings of the German botanist Georg Franck von Franckenau.) Painting or dyeing these eggs made the event even more celebratory, especially in using the colors red (for sacrifice) and green (for new life).

As a side-note that may interest Tor.com readers, this movement of the egg from Ēostre’s fertility connections to Jesus’ resurrection connections is paralleled in the Ukrainian folk-art of Pysanky (seen above), which in origin pre-dates Christianity but has very much subsumed its traditions into this new religious framework. (And a shout-out here to Amy Romanczuk’s Patterns of the Wheel, which embeds pysanky symbolisms into a coloring book for Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time.)

Why hide the eggs? Sadly, no, it’s not because Jesus was allergic. The hiding and finding of the eggs enabled believers to have a participatory connection to the finding of “new life” on Easter. An Easter Egg hunt also functioned as a reward if eggs weren’t eaten during Lent (the time leading up to Easter); finding an egg meant (finally!) getting to eat the egg.

As someone who doesn’t care for eggs in any way other than scrambled, I’ve got to admit I’m super-glad this “treat” notion has left real eggs behind in favor of chocolates and jelly beans.

Anyway, whether you and yours religiously celebrate Easter or just religiously eat Peeps, here’s hoping you all had a wonderful holiday this year!

Originally published April 2017 as part of the Medieval Matters series, and again in March 2018.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.