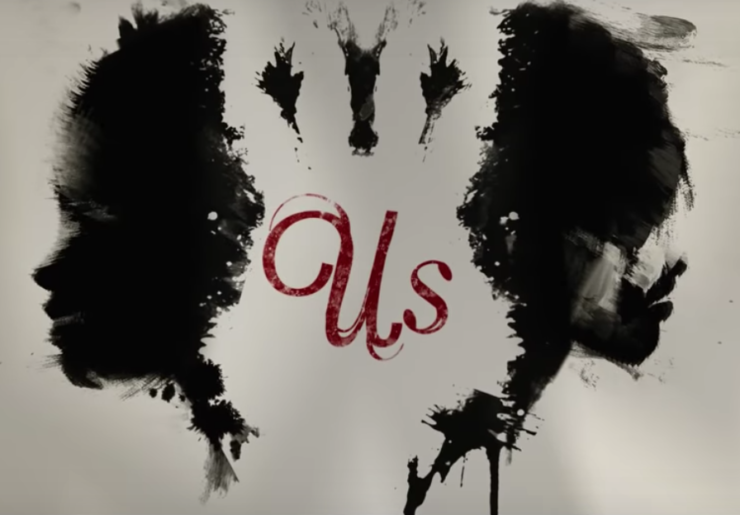

One of the unexpected pleasures of Jordan Peele’s Us has been tracing its various influences and allusions. In the weeks since its release, culture writers have been going nuts pointing out the movie’s overt references and placing it within genre traditions.

But as useful as these discussions have been, they’ve largely focused on movies. Of course, that makes sense—Us is a movie, and its main point of reference is other movies.

However, Us is not the first piece of science fiction to address troubling issues of community and inequality through fantastic ideas and imagery—not by a long shot. Two of the most accessible pieces working on this theme are the short stories “The Ones Who Walked Away From Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin and “Speech Sounds” by Octavia Butler. While readers of sites like Tor.com are likely to be quite familiar with both of these authors, the film is such a rich, overdetermined amalgamation of ideas, purposeful echoes, and pop cultural references that it encourages excavation—so let’s take a look at both stories, and the points where they connect with or reflect the film. While Peele may not have had these specific stories in mind while writing and filming Us, it’s clear that all three works share some thematic DNA, and that the ideas and anxieties expressed in each overlap to a significant degree.

A Movie About Us

At its core, Us is a horror story about an upper middle-class family—Gabe and Adelaide Wilson (Winston Duke and Lupita Nyong’o), and their children Zora and Jason (Shahadi Wright Joseph and Evan Alex)—whose vacation in Santa Cruz is cut short when a family of doppelgängers break into their beach house. Dressed in red jumpsuits and carrying golden scissors, the doppelgängers—led by Adelaide’s double Red (also played by Nyong’o, with a creepy, creaking voice)—claim to be the result of an abandoned government project, left in underground tunnels to mimic the behaviors of their above ground counterparts, tethered miserably to the actions and decisions of the privileged.

As the only doppelgänger with the ability to speak, Red leads her fellow Tethered in a “Hands Across America”-inspired revolution. She convinces the Tethered to rise from the tunnels, to kill their counterparts above ground, and announce to the world that they exist, that they cannot be ignored.

Like a lot of great science fiction pieces, the mechanics of Us don’t make a lot of sense, and various theories to explain how the Tethered operate and where they got their nifty scissors produce only unsatisfying answers. Such questions and demands for logical explanations ignore the proverbial forest for the metaphorical trees, however: At the risk of sounding like every film snob ever, Us isn’t about what the Tethered are—it’s about what the Tethered represent.

And what do they represent? We can ask them ourselves. When Gabe demands to know who they are, a wide smile covers Red’s wild-eyed face, as if overjoyed at the opportunity to finally identify herself. “We’re Americans,” she declares with pride.

The Tethered represent the Americans, disenfranchised and made monstrous by the American lifestyle—the shadow selves whose suffering makes possible the privileges and benefits the rest of us enjoy. When Red describes the cold rabbit meat she had to eat and the dangerous toys she received at Christmas—the underground versions of the warm food and good gifts given to Adelaide—one cannot help but think about the homeless, the poor, and the destitute ground down by the same systems that give me the food in my belly, the books on my shelf, and the computer I use to type this article.

Us derives its strength not just from Peele’s direction, from the cast’s outstanding performances, or from Michael Gioulakis’s striking cinematography—it works because it plays on the knowledge all Americans share, that the same system that rewards us punishes others. It works because it taps into the fear that someday, we’ll have to pay for that inequality.

Us in Omelas

One of Peele’s smartest creative decisions in Us was to make the Wilsons an “average” family—comfortable, but still aspirational. Sure, they have nice things like a good car and money to buy a (busted up) boat, but they aren’t nearly as rich as their friends Kitty and Josh Tyler (Elizabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker), who live in a fancier house, own every electric doodad available, and have an impressive (but unhealthy) alcohol budget.

Ursula K. Le Guin plays on that same point in her heavily-anthologized short story “The Ones Who Walked Away from Omelas.” Despite a name inspired by the mundane—a sign for Salem, Oregon spied by Le Guin in the rear-view mirror—Omelas is the most idealized of utopias. The city lacks an army or police, lacks priests or kings—anything that would place restrictions on its members. Instead, the people of Omelas have celebrations and parades and orgies, anything to live their lives as full citizens.

The story’s use of a “you” voice has a feeling of salesmanship, as the speaker seems to read the reader, anticipating the audience’s responses to the promises of Omelas. Just when the city sounds too fantastic to be taken seriously, the speaker addresses our skepticism. For instance, after inviting us to imagine a middle class, in which people “could perfectly well have central heating, subway trains, washing machines, and all kinds of marvelous devices not yet invented here, floating light-sources, fuelless power, a cure for the common cold,” she senses that she’s gone too far and pulls back: “Or they could have none of that: it doesn’t matter. As you like it.”

Instead of feeling scattered, this approach makes the city seem more realistic because we all know and recognize the experience of being sold to. All of us have encountered some salesperson or clerk making outrageous promises or playing on our vanities to make a sale. The speaker follows the acknowledgment that “Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale, long ago and far away, once upon a time,” by flattering us readers: “Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it however you want to… for certainly I cannot describe well enough to suit you all.”

As this offer indicates, the speaker creates this fictional city with the reader in mind, giving us the community of our dreams and inviting our participation in that world—both its virtues and its crimes.

Exasperated with trying to explain the plausibility of Omelas, the reader finally turns to the one thing sure to make us believe: “a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, or perhaps in the cellar of one of its spacious private homes, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window,” in which, on a dirt floor, “a child is sitting.” As the narrator explains, the citizens “all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.”

In that moment, the speaker knows that we readers believe. We may not believe in a world without war, but many of us live a life untouched by violence. We may not believe in a city of unwavering abundance, but many of us never go hungry and have fantastic inventions in our pockets. We may not have lavish robes, but many of us wear warm and stylish clothes.

And we all know, on some level, that these things come from the suffering of others. That suffering may be indirect, a by-product of the capitalist system in which we participate. Or that suffering may come from the sweatshops in which people work to death to provide affordable electronics and clothes. But we know we both cause and benefit from suffering, and thus we believe in Omelas.

The story ends with the speaker describing the various responses to this child. Some try to rescue the child, but decide that they can’t and give up. Some choose to forget what they saw or engage in rationalization, justifying the benefit of many at the cost of a few, and simply return to enjoying the city’s splendor. But some refuse to participate anymore. Some walk away from Omelas.

In the same way Us makes monsters out of everyday, comfortable middle-class Americans who just want to live their lives, Le Guin’s story forces us to admit what we wish we didn’t know. It gives us a model of behavior for confronting the suffering of others—impotent rage, willful ignorance, or intentional non-participation—but leaves the ultimate decision to us.

The Sounds of Us

For reasons Us explains in its final act, Red leads the Tethered because she is special, different. This difference is largely expressed in the fact that only she has the gift of speech—albeit a garbled, unsettling speech. The rest of the others can clearly communicate among themselves, but they express themselves in gestures, grunts, howls, cackles: animalistic noises that underscore their otherness and allow us, the audience, to consider them less than human. Because Red can speak, she provides the link between the Tethered and the rest of the world.

The power of speech and the horror of its loss drives Octavia Butler’s short story “Speech Sounds.” Set in a not-quite post-apocalyptic California, “Speech Sounds” follows the attempts of a woman named Valerie Rye to make her way to Pasadena. A mysterious disease has struck America, stripping most people of their ability to speak or read. Those like Rye, who can still talk, still lose the ability to read, and must keep their ability a secret, lest they be destroyed by jealous others.

Butler subtly shows the centrality of speech for our understanding of humanity by giving us a society not in ruins, but in permanent disrepair. The highway system still works, and buses and other vehicles still operate, but they do so in arbitrary or rudimentary fashion. The man driving the bus Rye rides at the start of the story responds to threats with violent grunts, and posts on the side of the bus “old magazine pictures of items he would accept as fare on its sides. Then he would use what he collected to feed his family or to trade.” Obsidian, the man who can read but can’t speak, and who befriends Rye, wears a police uniform and carries a gun because those symbols carry weight, even if the police force itself has disbanded.

Rye’s world functions like a shadow of the one we know, where familiar and mundane activities like walking down the street and encountering strangers becomes ugly, twisted, and horrific. Without words, basic human relationships become strained and fraught.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

We see this play out in nearly every encounter in the story, including the opening scene in which an otherwise innocuous disagreement on the bus quickly explodes into a full-on brawl. But the most important example of humanity warping and twisting in the absence of speech occurs in the budding friendship between Rye and Obsidian. Without words to bind them (or other satisfactory means of communication, like a shared sign language), the two have to perform and interpret a series of gestures and symbols to interact:

The bearded man sighed. He glanced toward his car, then beckoned to Rye. He was ready to leave, but he wanted something from her first. No. No, he wanted her to leave with him. Risk getting into his car when, in spite of his uniform, law and order were nothing—not even words any longer.

All of Rye’s communication with Obsidian follows a similar pattern. Instead of exchanging names, the couple needs to show one another their “name symbols,” “a pin in the shape of a large golden stalk of wheat” for Rye and a “pendant [with] a smooth, glassy, black rock” for Obsidian. Instead of admiring one another for their abilities—Rye’s speaking, Obsidian’s writing—the two have to fight their feelings of jealousy. The illness has not only crippled society, but it has also diminished the survivors’ abilities to maintain their humanity, abilities Rye and Obsidian struggle to keep.

With its depiction of humanity reconfiguring itself in the wordless shadow of civilization, “Speech Sounds” gives us an idea of the Tethered’s life in a manner more satisfying than the fan theories that try to fill supposed “plot holes” in Us. During their climactic battle, Red tells Adelaide that while the government figured out how to copy the body, they never learned how to recreate the soul, leaving “two bodies sharing one soul.” The speechless people of “Speech Sounds” helps us imagine what that life must be like, and invites our sympathy with the lookalikes, the others, of Us. After reading “Speech Sounds,” we understand why the Tethered would try to so desperately to rise up get the full lives hoarded by those above ground.

This isn’t to say that either “Speech Sounds” or “The Ones Who Walked Away From Omelas” was a direct influence on Peele or the movie. But in considering Us as part of the rich sci-fi tradition to which both of these stories belong, we can gain a better understanding of the tensions and fears, both individual and cultural, that continue to drive this tradition, and a deeper appreciation for the works that confront and examine these fearful truths so memorably.

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.