Meet Roger. Skilled with words, languages come easily to him. He instinctively understands how the world works through the power of story. Meet Dodger, his twin. Numbers are her world, her obsession, her everything. All she understands, she does so through the power of math. Roger and Dodger aren’t exactly human, though they don’t realise it. They aren’t exactly gods, either. Not entirely. Not yet.

Meet Reed, skilled in the alchemical arts like his progenitor before him. Reed created Dodger and her brother. He’s not their father. Not quite. But he has a plan: to raise the twins to the highest power, to ascend with them and claim their authority as his own.

Godhood is attainable. Pray it isn’t attained.

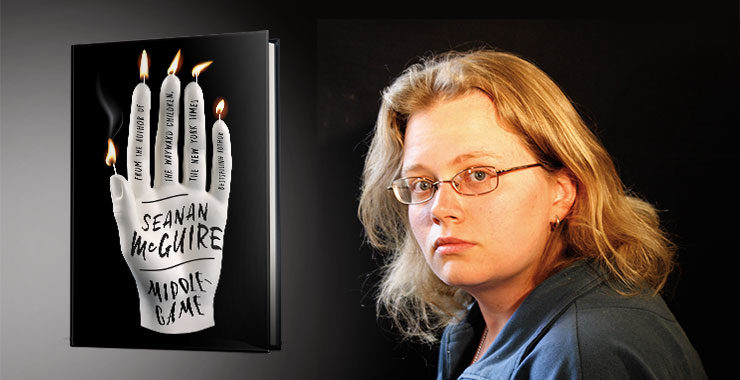

Author Seanan McGuire introduces readers to a world of amoral alchemy, shadowy organizations, and impossible cities in the standalone fantasy, Middlegame, out from Tor.com Publishing on May 7th. Read Part Three below, or head back to the beginning with Part One!

BOOK I

The Second Stage

Mathematical science shows what is. It is the language of unseen relations between things.

—Ada Lovelace

Sorrow is knowledge.

—Lord Byron

One Hundred Years Later

TIMELINE: 23:58 CST, JULY 1, 1986.

For a man on a mission, a hundred years can pass in the blinking of an eye. Oh, it helps to have access to the philosopher’s stone, to have the fruits of a thousand years of alchemical progress at one’s fingertips, but really, it was always the mission that mattered. James Reed was born knowing his purpose, left his master in a shallow grave knowing his purpose, and fully intends to ascend to the heights of human knowledge with the fruits of his labors clutched firmly in hand. Damn anyone who dares to get in his way.

Damn them all.

He waits at the end of the hall for his moment, standing in the place where the light, by careful design, fails to reach. Asphodel taught him everything she could: he learned the delicate arts of alchemy and the blunter arts of the con side by side, drinking knowledge like mother’s milk. This is all a show, and these men—these craven, prideful men, who think themselves kings of their corporate veldt—are his rubes, ready to be taken for everything they have.

(The Alchemical Congress does not approve of his dealings with the more mundane world, calling them risky and arrogant. The Alchemical Congress has no room to speak. Its members are arrogance personified, and their day of reckoning is coming sooner than they can possibly know or understand. Oh, yes. They’ll learn soon enough that they should never have crossed Asphodel Baker, or by extension, her son, heir, and greatest creation.)

This is his sideshow of wonders, his collection of freaks, laid out for the edification and carnival-glass seduction not of the masses, but the chosen few:

The hall is wide enough to accommodate two stretchers side-by-side, lit by glass-screened bulbs too dim to show the color of the floor. They barely illuminate the walls, which could be white, or cream, or gray; the light is too diffuse to make their color clear. Rooms dot the hall. The bulbs inside them are brighter, illuminating the occupants behind the individual one-way mirrors, throwing them into a stark, clinical relief that carries them from “child” to “curiosity.” They range in age from two to twelve. They wear colorful pajamas blazoned with cartoon bears, or spaceships, or comically friendly dinosaurs; they sleep under blankets decorated with more of the same; and yet, thanks to the light, they barely register as human.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

One little girl has crammed herself into the corner of her room. She is a watchful, doe-eyed thing, sitting with her arms wrapped around her knees and her eyes fixed on the mirror, staring like she can somehow see the men outside. Her companion sleeps under a blanket covered with cartoon robots, his back to the rest of the room. According to the label outside their window, their names are Erin and Darren, and they are five years old, and there is nothing about them that has not been done by design.

But the focus of this day is outside the cells. It’s on the men, three of them, soft, balding creatures in respectable business suits and sensible shoes. They would fit perfectly into a boardroom or stockholder’s meeting. Here, in this precise, perilous place, they are as out of their element as a blizzard in a volcano. They cluster together, uneasy. This is their doing as much as anyone else’s; they were the ones who dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s and signed the checks that made it all possible. They own this. They own every inch of it. And yet…

James Reed smiles as he watches them. Their unease is intentional, part of the balance of power. These investors may own everything they see, but he created it: here, he is God Almighty, capable of bringing life out of nothingness, able to command the forces of the universe. They would do well to remember that, these small men with their narrow minds and unstained hands. They would do very well indeed.

Behind the glass, a boy with eyes the color of concrete is rocking back and forth, looking at nothing. He has been humming for the last seven hours. Tiny microphones in his room—never “cell,” this is not a prison, this is a breeding ground for the future, and language is incredibly important here—have recorded every second of his meandering tune. Nothing is wasted, ever. Nothing is allowed to slip away.

(Later, cryptographers will reduce his song to its mathematical components, eventually determining that he’s been offering them a chemical formula, one atom at a time. The formula will yield a novel painkiller derived from several unexpected sources, nonaddictive and capable of offering relief to cases previously thought hopeless. Patenting and marketing the drug will take another twelve years, but the results will make billions for the shell company that handles the pharmaceutical side of things. Bit by bit, because of moments like this one, the lab becomes self-sustaining. It is already vast, and sprawling, and unspeakably expensive in the way of vast, sprawling things. And it must sustain itself, it must. If the Alchemical Congress paid a penny for its creation and upkeep, they would expect their investment to turn into ten times its weight in gold—and that cannot be allowed. Not now. Not with the Doctrine so close at hand.)

“Gentlemen.” Reed times his speech carefully: it emerges from the shadows and he emerges on its heels. Each step he takes highlights the disparities between him and his investors. They wear cufflinks purchased by their wives, their balding pates polished to a mirror sheen. He dresses like a character from a Ray Bradbury story of the endless American twilight: tight black trousers, a buttoned-up shirt in sapphire blue, even a tailcoat with bands of strange glyphs embroidered around the cuffs and bottom hem. The embroidery is gold, a reminder of the promises that drew these men to his side, moths lured by the promise of an all-consuming flame.

Asphodel—master, mentor, martyr—taught him the value of showmanship. He was always an eager student, and he understands his audience. They must think him a distracted dandy, a character from a children’s story, something to be tolerated and disdained. They must allow their arrogance to treat him as a synecdoche, using his little affectations to complete an inaccurate picture.

They forget, these pampered creatures of the corporate veldt, that always there are predators, and always there is prey. They think themselves lions when even a casual onlooker can see that they are zebras, weak and plentiful and ready for the kill.

His claws, draped in velvet and wrapped in affectation, are sharp enough to slaughter the world.

“Gentlemen,” he says again, and his accent is all things and nothing at all. He has honed it over the span of a century, choosing plosives and sibilants to make him sound exotic and exciting without tipping over the line into “foreign.” There is a reason the children on display in this hall are pale, made of milk and bone, rather than earth and stone and all the other things his subjects are rooted in. The white children seem almost like human beings to these greedy, grasping men, and here, in this cold, sterile hall bridging science and alchemy, reason and religion, appearances matter almost as much as words.

Children who seem human create guilt in the men who paid for them. Guilt opens wallets. It’s simple racism and simple math, and it opens the chasm of his loathing even deeper, for who with any sense would reject any of the wonders the disassembled human race could have to offer?

“Dr. Reed,” says one of the men, the self-appointed leader of this little cluster, elevated by self-importance and, more, by a lack of self-preservation. The other two fall back in what he will interpret as reverence, but which Reed sees as cowardice. “Why are we here? You told our offices you had some great breakthrough to show us, but we’re seeing the same old things.”

Reed’s expression of shock would look almost comical on anyone else. Not on him. Never on him. Practice, as they say, makes perfect. “You’re seeing subjects who can tap into the future, who shuffle probabilities like cards, whose cells regenerate at a pace we can’t track on our equipment, and you call it ‘the same old things’? Why, Mr. Smith. I’m ashamed at your shortsightedness.”

The man—whose name is not Smith; he accepts the bland pseudonym as a necessity, as do they all. There are costs to doing business of this kind, hidden in the shadows and outside the boundaries of law—stands a little straighter, narrows his eyes a little more. He isn’t being taken seriously. This must stop. “You’ve shown us wonders, but those wonders aren’t marketable, Reed. We can’t transform all the world’s lead into gold without destroying the economy we’re trying to control. What can you possibly have to offer us?”

“At last you’re asking the right questions. Come.” Reed stalks away, as fluid as the predator he is. The men in their flat. soled shoes have no choice but to follow or be left here, surrounded by the staring, unseeing eyes of the children they’ve paid to bring into the world.

Not one of them hesitates to go.

The hallway stretches like a band of taffy, passing more white-walled rooms, revealing more pajama-clad children. Some are older, moving into their teens; they sit at desks with their backs to the liars’ mirror, aware that they could be under observation at any time. Others are younger, toddlers who play with brightly colored blocks or curl, innocently sleeping, under hand-stitched quilts. The people who care for them say it’s better if their possessions are made by hand instead of by machine; something about the process of creation flavors the inanimate, and the children sleep better when surrounded by things with a less sterile past. Childrearing is difficult under the best of circumstances. What is being done here is so much more complicated than that.

The door at the end of the hall boasts three locks and a keypad. Reed undoes each in turn, making no effort to conceal the code as he punches it in. It will be different by morning. The security is for more than just show: it’s a warning, making sure these men understand that the things he has to show them are to be taken seriously. If any of them attempt to challenge his sovereignty, there will be consequences.

The door opens. Reed allows the investors to enter first. When he follows them, the door slams behind him like a tomb being sealed, final and cold.

“The universe operates according to several basic principles,” he says, without preamble or pause. “Gravity, of course; probability. Chaos and order. We’re part of the universe, and so the things we embody are equal in divinity to the forces which act upon us from the outside. Gravity is important. No one wants to drift away because the bonds holding them to Earth have been carelessly shattered. But love, curiosity, leadership—those are equally important, or they wouldn’t exist. Nature abhors a vacuum. Nothing without purpose has been made.”

It is dark here, in this space that seems to have no exits; unless he unlocks the door again, there is no escape. None of the investors say a word. They are happy to exercise their power in small ways when there is no threat to them, but here and now, in this space, they are not in control. It vexes them. Reed can see that, and glories in it.

“As you’re aware, our research has been focused on the creation of children attuned to these so-called ‘natural forces.’ Imagine a child who embodies transmutation so well that their touch alone is enough to transform base metal, or another who can bleed night into day. Success would put the most powerful weapons of all time in our hands. The power would be beyond description. Each of you was chosen to invest with us not only because of your financial resources, but because your emotional resources put you in good standing to help shepherd the world into this new era of enlightenment and understanding.”

Every time he gives this speech, Reed worries he’s shoveling it on too thick: that this will be the time one of their placid, milk-fed cattle finally remembers it was once a predator, too, and begins biting the hand that strives to feed it. Every time, he is relieved and disappointed in equal measure as they swallow his words, smiling and nodding in satisfaction. Yes, of course a new order will rise, and it’s only natural that they should be at the forefront. They’ve earned it. They’ve paid for it, and by paying, they have made themselves entitled to every benefit, every opportunity. This is theirs, and no one else’s.

Fools. But wealthy fools. Wealth has carried the project this far, away from the cowards of the Congress, to the point where they can become self-sustaining, where they can cut ties to businessmen who look at the miracle of the age and see only dollar signs. Not much longer now, and they can be free. Reed holds that thought firmly as he continues.

“Central to our efforts has been a force defined by the ancient Greeks: the Doctrine of Ethos. According to the Doctrine, music can influence individuals on an emotional, mental, and even physical level. Knowing as we do now that each individual is a microcosm for the creation, it seems obvious that something which can work on a single human could also work on the entire world. Alchemists have been striving to embody the Doctrine ever since.”

Reed pauses, giving them time to absorb his words. Then, to his surprise, one of the investors speaks.

“I was here nine years ago, when you told us you’d succeeded at doing exactly that. Why are we going over old ground?”

“Because if you were here nine years ago, you understand that our initial success was, in many ways, a failure.” Reed schools his expression with difficulty. How dare this man speak to him like that, as if he had any concept of the trials inherent in an undertaking of this nature? They are changing the world, and this man, and the men like him, only care about the color of the ink in their ledgers.

The investors are muttering amongst themselves now. He’s losing them.

“Our first attempt to embody the Doctrine was a success,” he says, before mutters can become outright revolt. “We forced a guiding principle of the universe into human flesh. There have been… complications, yes, but the theory remains sound.”

Complications: a boy with so much of reality resonating in his head that he can’t be bothered to interact with anything beyond what he sees behind his closed eyes. The child has never spoken. He stopped eating three years ago, and while he still lives, sustained by clever machinery and feeding tubes, he hasn’t opened his eyes in eighteen months. The Doctrine is imprisoned within his shivering skin. There’s no way to extract it, to make the world dance to their whim, save for giving it a new home and putting its old one in the ground.

“The difficulty of the Doctrine is its size. When placed inside the mind, there’s no room for humanity. We believe that by splitting the Doctrine into its component parts—mathematics and language— we can create a gestalt of sorts. Two people who will embody the concepts we’re attempting to harness, but whose abilities will be limited enough when separated that they will remain pliable and easy to control.”

“How pliable?” asks an investor.

“Pliable enough. We’ve arranged for an upbringing that will both encourage their endangered humanity to flourish, and teach them that pleasing us is paramount. Once they’re reunited, they’ll do whatever we ask if they want to stay together—and they will. Their natures will leave them no choice, and we’ll have them. We’ll control their access to everything, including each other.” What sweet torment it will be for them, these cuckoo children of the Doctrine, to be denied their other halves until he deems them worthy of reunion. “They won’t be ordinary children—that is denied to them, and gloriously so—but they’ll change everything.”

“How long can we expect to wait before we know whether this is another failure?” asks Mr. Smith.

Reed grits his teeth. “That’s what I’ve brought you here to see,” he says. He snaps his fingers, and the wall rolls up, revealing three small white rooms. The first two are occupied, one by a pair of children coming on two years of age, the second by a pair of sleeping babies, no more than a year old. The third is empty, save for two isolated bassinets.

The investors gape and goggle at these children like creatures in a zoo. Reed allows himself to smirk.

“We’ve already succeeded,” he says. The door at the back of the third room opens and two nurses step inside, each with a babe in arms. The newborns are placed reverently on their mattresses. The nurses slip away.

Three sets of children, representing three years of births. All were delivered by Cesarean section at the stroke of midnight, ripped from their mothers when the time was right, each pair divided by a single rotation around the sun. The original incarnate Doctrine will be gone by now, released from his earthly form as soon as the third pair of carefully tailored children drew their first unhappy breaths. All six of them are worthy hosts, and who owns the Doctrine now is anyone’s guess.

Well. Not anyone’s. No matter which of these pairs has drawn the concept home, they still belong to him.

“Gentlemen, I give you the Doctrine of Ethos,” he says. “One of these pairs will embody everything we have been working toward, and when they do, the universe is ours.”

Ours, and not yours, you pompous, shortsighted fools, he thinks. The investors crowd around the glass, fighting for a better view of their future.

The babies sleep on.

Later, when the investors have been ushered out, red-faced with excitement and buzzing about how the world is going to change, how they are going to change the world, Dr. Reed shrugs off his tailcoat and returns to the lab to check on his newest creations. The technicians and laboratory assistants whose shifts have kept them here this late into the night look up when the door swings open, paling before rushing to resume their duties. None of them want to catch his eye. Sometimes he has ideas about how things should be done. Sometimes those ideas are enforced in ways that leave scars.

Reed walks with shoulders back and head held high, content with the way things are progressing. Those fools in the Congress said it couldn’t be done, said no man could blend science and alchemy without losing the best parts of both, drove Asphodel to lengths beyond imagining to prove them wrong, and now here he is, king of all he surveys, dragging the old ways into the new world one inch at a time. There have always been avatars, he argued when this began; all he seeks to do is bring them under proper control. Maybe Asphodel’s ideas gave him his starting point, but by God, the rest has been his own.

(Summer kings and snow queens, Jacks in the green and corn Jennies; he knows the names, knows the secret stories whispered about them in the dark places of the world. He knows better than to try for the naturally incarnate concepts. That will come later. When he controls the Doctrine, when cause and consequence dance to his commands, then he’ll be able to reach out and collect the other things that should be his by right. He’ll hold the universe in his hands, and woe betide any who question what he chooses to do with it.)

“There you are.” The voice is accompanied by a woman popping around a corner like a cork out of a bottle, his own personal djinn in blue jeans and flannel. Leigh is the finest alchemist he’s had the misfortune of meeting since Asphodel’s death, a whirlwind of motion with acid holes in her shirt and hair kept short to minimize the amount of time it spends on fire. She has a wide, honest face, freckles scattered like stars across the bridge of her nose. She looks like peaches and cream, like Saturday afternoons down by the frog pond, innocence and the American dream wrapped up in a single startlingly lovely package. It’s a lie, all of it. He believes in exploiting the world for his own gains, but she’d happily ignite the entire thing, if only to roast marshmallows in its embers.

She is deeply flawed, and impossibly useful, and he’ll enjoy the day when he’s finally in a position to take her apart and reduce her to the components her originating alchemist used to make her. The old fool forgot the lessons of Blodeuwedd and Frankenstein: never create anything smarter, or more ruthless, than yourself.

Something about that thought bothers him—something about Asphodel, who was many things, but was never a fool. He shoves the thought aside, focusing on Leigh. “How was the delivery?”

“Smooth. Fine. Butter. Whatever word you want. The excess material has been harvested and disposed of.” She waves a hand carelessly. “Nothing out of the ordinary.”

He knows when she says “excess material,” she means more than just the afterbirth, which will possess strong alchemical properties of its own, thanks to the method of the manikins’ creation. She means the woman who gestated them, unwitting surrogate to a pair of cuckoos. He doesn’t know where Leigh found the surrogate, and he has enough humanity—if only barely so—not to ask. The cost of having his composite alchemist’s brilliant mind at his beck and call is that she’ll occasionally do things like this—and because of the woman’s long proximity to the subjects, her body may be of alchemical interest. It’s never possible to know in advance.

“The boy?”

“Dead. Waiting for you in your private lab. I know you wanted the honor of the dissection.” Her lips draw back from her teeth in displeasure. When something needs to be taken apart, she prefers to do it herself.

Reed pays her unhappiness no mind. “And the subjects?”

“The male was removed from the womb first, which means he’s likely the control; he’s fine, healthy, and ready to ship to his adoptive family. The female was extracted less than two minutes later. She screamed for half an hour before she settled down.”

“What calmed her?”

“The male. When we put them together, she doesn’t cry.” Leigh’s mouth quirks. “Isn’t the flight to her new home going to be fun?”

Reed nods. “And the others?”

“The adoptions have been arranged. We’re cutting along the Humors. Two each to Fire and Water, one each to Earth and Air.” For the first time, Leigh’s veneer of confidence cracks. “Are you sure about sending them out? I mean, really sure? I’d be more comfortable keeping them here, under controlled conditions.”

“The girl—”

“All of them.” Leigh shakes her head. “These children are irreplaceable. There’s never been anything like them in the world. They belong here, where they can be studied. Monitored. Managed. Putting them into the wild is asking for something to go wrong.”

“The plan has been carefully designed to maximize the chances of success.”

“You call this ‘careful design’? Placing half of each pair with a civilian family, that’s being careful? At least the other half will be with our people, but that’s not good enough. This isn’t how we control our investment.”

Reed knows what they’re doing: was the one who designed the protocol. Somehow, he manages not to scowl. “I was unaware that this was ‘our’ investment,” he says.

Leigh waves a hand dismissively. “You know what I mean.”

“Do I? Do I really? We’ve been over this. A certain amount of randomness must be introduced if we want the children to learn to access their abilities. We know strict lab conditions don’t work.” More, by raising them away from the lab, they avoid the risk of their subjects learning too much, too soon. Knowledge is power, for these cuckoos more than most. If he keeps them ignorant, he keeps them tractable—and oh, how he needs them to be tractable. Tractable things are so much easier to control.

“At least let us keep one of the pairs here. The newest. They’re young, they won’t know anything beyond what we show them. We can raise them in boxes, keep them apart, control everything they see and hear. We’ve tried absolute isolation together. We haven’t tried it apart.”

“Because it would break them.”

She shrugs. “Some things need to be broken.”

Things like you, he thinks, as aloud he says, “My will is law here, Leigh.”

“But—”

“My will is law.” His hand lashes out, grabbing her throat, slamming her back into the wall. Her eyes gleam with malicious delight. This is what she wanted: the reminder that he is the superior predator, that he has earned his place at the top of their tiny pecking order. How he wearies of the violence. How he understands its necessity. “Do you understand?”

“Yes,” she whispers.

“Yes, what?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good girl.” He releases his hold on her throat, pulling his hand away and straightening his collar. “Believe in me, Leigh. That’s all I ask. Believe in me, and I will lead you to the light.”

“And the light will guide us,” Leigh says, ducking her head until her chin almost brushes her sternum.

“We’re following the correct path,” says Reed, touching her shoulder.

As soon as his hand finds her flesh, the alarm begins to ring.

Both of them stiffen, heads snapping up, eyes scanning the lab for some sign of what’s gone wrong. All around them, the technicians who have studiously ignored their disagreement are doing the same, checking their equipment, calling up chemical readouts. Reed is the first to move. He pulls his hand away from Leigh and runs for his private lab. The door is closed, but opens at the swipe of the card he wears on a lanyard around his neck.

Inside, an astrolabe, spinning endlessly, occupies half the space in the vast room. Reed freezes in the doorway. Leigh, sliding to a stop behind him, does the same, as both of them stare.

The dance of planets was calibrated by a master’s hand, designed to mirror the heavens exactly. Asphodel poured years of her life into the spectacular machine, thinking it would be a key component of her legacy—and as her final, crowning touch, she knocked it outside of time, so that it could someday be used to chart the movement of the Doctrine. Reed has taken great pleasure in locking it away, using its mechanical horoscopes solely for his own gain. It is a wonder of technical alchemy. Only a great and terrible misuse of the forces of nature could damage this edifice of gold and copper and spinning jewels…

And it’s running in reverse.

Slowly, Reed smiles.

“You see?” he says. “We don’t need to wait to know if this is going to work. We’ve done it. All those old fools who thought they could control the world—Baker, Hamilton, Poe, Twain, even poor, damned Lovecraft—they failed, and we’ve succeeded. Two of those children, two of those six clever, clever children, have just reset their personal timeline. It works.” He turns to her, beaming.

“We’re going to control the world.”

Leigh cocks her head, following his words to their logical conclusion. “Does that mean we don’t need the bankers anymore?”

When keeping predators on a leash, it’s important to give them room to run. Reed nods. “Yes,” he says. “But make sure they understand why we’re terminating our agreement. It’s always better, when they understand.”

Leigh’s face splits in a smile as bright and wide as the gateway to the improbable road. In that moment, she is more terrible than she is beautiful, and Reed wonders how the alchemist who made her could ever have missed the warning signs.

“It will be done tonight,” she says.

“Good. I have business with the Congress. Everything is proceeding exactly as it should.” He tilts his face toward the window, his own smile smaller, and tamer, than Leigh’s. “The Impossible City will be ours.”

Behind him, Asphodel Baker’s astrolabe continues to smoothly rewind, and all of this has happened before.

Excerpted from Middlegame, copyright © 2019 by Seanan McGuire.