Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

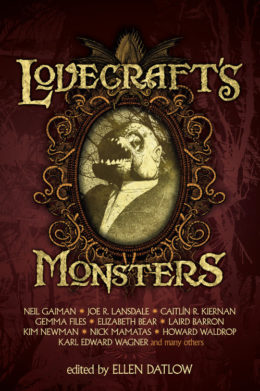

This week, we’re reading Karl Edward Wagner’s “I’ve Come to Talk With You Again.” You can find it most easily in Lovecraft’s Monsters; it first appeared in Stephen Jones’s 1995 anthology Dark Terrors: The Gollancz Book of Horror. Spoilers ahead.

“The music box was moaning something about ‘everybody hurts sometime’ or was it ‘everybody hurts something.’”

Summary

Jon Holsten is an American writer hailed as the “finest of the later generation of writers in the Lovecraftian school,” which earns him a modest living and an annual trip to London. He meets five of his old mates at a pub called the Swan, where the smell of mildew and tobacco irritate his nose, the racket of jukebox and pinball machine his ears. More depressing is the realization that in years past there would have been eight or ten around the table. Cancer, weak lungs and drug dependence have taken a toll this year alone. So it goes.

Present friends have their own health problems: hacking cough, diabetes, heart disease, obesity, alcoholic liver. All five, by Holsten’s reckoning, are about forty years old. They marvel that Holsten at sixty-four looks twenty years younger and remains superbly fit. What’s his secret? A portrait in the attic, Holsten jokes. Pressed, he falls back on vitamins and exercise.

Over the rim of his glass he sees a figure enter the pub clad in tattered yellow robes, face hidden behind a pallid mask. Its cloak brushes a woman, who shivers. As it seats itself at the friends’ table, Holsten tries without success to avoid its shining eyes. Memory floods him of a black lake and towers, of moons, of a tentacled terror rising from the lake and the figure in yellow pulling him forward, then lifting its pallid mask.

Is Holsten all right, a friend asks, shaking him out of the waking nightmare. Fine, Holsten says. He watches the tattered cloak trail over another friend’s shoulders and knows that this fellow’s next heart attack will be fatal. The figure studies a third friend—one who will soon throw himself in front of a tube train, drained and discarded. It peers over the shoulder of a fourth, who doesn’t notice it.

None of them do.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

The tentacles grasp and feed, drawing in those who’ve chosen to come within their reach. There were promises and vows and laughter from behind the pallid mask. Was the price worth the gain, Holsten wonders. Too late. It was in a New York bookstore where he found the book, The King in Yellow, pages from an older book stuffed into it. He thought it a bargain. Now he knows it didn’t come cheap.

Holsten excuses himself to return to his hotel: Someone wants to interview him. The kid’s name is Dave Harvis, and he’s already waiting in the lobby when Holsten arrives. Harvis doesn’t recognize his idol, however; he was expecting a much older man, he stammers.

“I get by with a little help from my friends,” Holsten says. In memory, the tentacles stroke and feed. They promise what you want to hear. The yellow-cloaked figure raises its mask, and what is said is said, what is done is done.

Recalled by Harvis’s concern, as he was by his friend’s earlier, Holsten suggests they go into the hotel bar where it’s quiet. Harvis buys two lagers, sets up his cassette recorder. He’s got some friends coming by later, he says, who want to meet their idol. The figure in tattered yellow enters and regards Holsten, and Harvis.

Harvis fumbles with his cassette tape. Holsten feels a rush of strength. Into his pint he mumbles, “I didn’t mean for this to happen this way, but I can’t stop it.”

Harvis doesn’t hear.

Neither do any gods who care.

What’s Cyclopean: For the finest of latter-day Lovecraftian writers, Holsten is pretty pedestrian in his vocabulary.

The Degenerate Dutch: Everyone in this story appears to be a middle-aged white guy, except for one who’s indeterminately older, and a younger fellow being brought in to… supplement… the middle-aged crowd.

Mythos Making: Look into the eyes of the King in Yellow, and see the dark and terrifying shores of what is presumably Lake Hali.

Libronomicon: “Confirmed bachelors” Dave Mannering and Steve Carter run a bookshop. That is not where Holsten bought his copy of The King in Yellow, and whatever older work he found within.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Holsten’s “friends” are anxious about a variety of health issues, and understandably so.

Anne’s Commentary

And we’ve come to talk again, in hushed whispers, about Carcosa and the black lake of Hali and the King in his saffron tatters. Hastur has worn many masks, pallid and otherwise, since Ambrose Bierce created the benign god of shepherds whose name Robert W. Chambers borrowed for his “King in Yellow” stories. Lovecraft spiced “The Whisperer in Darkness” with mentions of Hastur and his cult, supposed enemies of the Mi-Go. Derleth expanded Hastur into a Great Old One possessed of octopoid morphology and a King in Yellow avatar. And, as Karl Edward Wagner puts it, so it goes, on and on.

We can thank Chambers for the King in Yellow’s fictional endurance. It’s amazing, really, how with a few allusions and a couple brief passages from the play of the same name he fashions a figure of such charismatic enigma. We have “Cassilda’s Song” and the bit from Act I in which Camilla and Cassilda urge the “Stranger” to unmask. He tells them, however, that he wears no mask. (“No mask? No mask!” Camilla gasps. That’s right, my dear. What you see is what this Stranger is.)

But can we trust what we see? What if we only see what we want to see, with clarity of vision coming too late?

Wagner’s Jon Holsten would have to agree with Kierkegaard: Life can only be understood backwards. And that includes eternal life, or at least unnaturally prolonged vitality. When you’re living life forwards, one seemingly inconsequential decision at a time, can you really be held responsible for mistakes like, oh, picking up a bargain-priced copy of Chamber’s King in Yellow? So what if the book’s stuffed with pages of what can only be King in Yellow, the dreaded play? Just because Holsten’s a writer of Lovecraftian tales doesn’t mean he’s superstitious; was Lovecraft, after all? Holsten and his readers may delight in the ageless trope of the book not meant to be read, of knowledge too dangerous to plumb, but Holsten doesn’t believe in any of that. Come on. Nobody can blame him for perusing the play, even into Act II.

Nor can anyone blame him if, after a visitation from the King in Yellow, Holsten follows the ragged spectre to Carcosa. Turn down a chance to collect that kind of first-hand material? What Lovecraftian writer worth his Curwen salts would do that?

Holsten is eager to dodge blame, all right. The trouble is that the most powerful self-deception is no match for what Holsten alone can see and what he precognates. The point of view of “I’ve Come to Talk with You Again” is complex, third person with a focus on Holsten but also seemingly third person omniscient. We readers listen in on the thoughts of Holsten’s friends. We even learn their sad futures, as in Crosley’s suicidal dive in front of a train. Who is telling us all this? Wagner as narrator? I think his approach is more sophisticated. I think that Holsten himself knows what his mates think and knows their ends, because the King in Yellow knows all this and passes it on to him through whatever torturing link they’ve developed. Torturing for Holsten, that is. Probably quite gratifying for the King, who in Wagner’s version of the iconic figure resembles another iconic figure: Satan. The King is that demonic lion that walks the earth hungry for souls, which he devours in his (true?) tentacled form, the beast of the black lake in Carcosa-hell.

But Christianity is much younger than Cthulhu and Hastur, the Lord of R’yleh’s “half-brother.” Someone in Holsten’s position might conclude that it was Hastur which came first, being a cosmic reality on which human mythologies were later based. Myth both warns and soothes. The warning: Avoid those who tempt you with exactly what you want most. The balm for victims of the King: What human could possibly understand such a being, beside which Satan is limpidly transparent?

It isn’t balm enough for Holsten. He likes to repeat his Beatles-inspired line, that he gets by with a little help from his friends. The truth is that he gets by on the very vitality of his friends, sickening them unto death. More casual associates, like fan-interviewer Harvis, also feed him. That’s more than a little help. That’s a form of vampirism, and the worst of it may be that Holsten gets just a small percentage of what’s drained, with the King/Hastur taking the, ah, lion’s share but feeling no guilt about it. Why should they, uncaring deities that they are?

I’m taking a guess that the song Holsten disparages at the beginning of the story is the Eagles’ “Heartache Tonight.” That came out on a 1979 album, which would make it current in 1980, the year John Lennon died—he being one of the two Beatles dead by 1995, when Wagner published “I’ve Come.” Or one of the three Beatles, including Stuart Sutcliffe and (as Holsten belatedly recalls) Pete Best. The actual Eagles lyric is “Somebody’s gonna hurt someone before the night is through.” Holsten wouldn’t like to hear that, given he was the hurter, and so he finally makes out the line as “everybody hurts somebody.” There’s a little comfort in that—he’s not the only predator, right? Right? And as he mutters into his lager as Harvis’s energy begins to filter to him, “I didn’t mean for this [my extended life] to happen this way [at the cost of your shortened one].”

He can’t stop the process now. But he didn’t have to start it. As Holsten admits to himself in flashback to the unholy doings in Carcosa, he deliberately chose to submit himself to Hastur. Another telling song lyric is evoked by the story’s title. Being a Simon and Garfunkel fan, I immediately heard them singing the first line of “The Sound of Silence.” It’s not exactly “I’ve Come to Talk with You Again.” Wagner wisely leaves off the first few words, which confirm Holsten’s guilt. It’s “Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again.”

No doubt about it. “Darkness,” paradoxically in shades of yellow, has become a closer friend to Holsten than any of the mates he dooms.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Simon and Garfunkel may seem at first glance like an odd choice to title a cosmic horror story, particularly a story about the sanity-breaking, world-shifting King in Yellow. But if darkness is an old friend to whom you sometimes say hello, it’s probably irresistible.

It really isn’t the author’s fault that I spent half the story earwormed by the gently dystopian strains of “The Sound of Silence,” and the other half imagining Yakko from Animaniacs shouting “Helloooooo Darkness!” at an extremely confused, yet suddenly cartoonishly ineffectual, King.

It is the author’s fault that the story wasn’t sufficiently diverting to distract me from this more compelling image. The King in Yellow is up there with the Yith for my favorite cosmic horror ideas, the ones I will read every bloody take on in the hopes that they’ll live halfway up to the original. And there are some good successors to Chambers, most notably Robin Laws and his stories unpacking and expanding the unreliable histories of “The Repairer of Reputations.” But Wagner is no Laws, and his King is a thoroughly reliable shadow of the original. There’s a mysteriously appearing book in the background, sure, but for me it doesn’t make Holsten a more intriguingly doubtable narrator, just a guy with a really screwed-up symbiotic relationship.

Honestly, the story might have worked better without the tentacle predator/symbiote labeled as the King, and if the original publication hadn’t been in a much more generic horror anthology I’d suspect him of tacking on the reference. Because there’s the core of something interesting here, a deal with the devil that actually works reasonably well for the dealer, assuming that his conscience provides minimal pinpricks. Holsten gets fame, moderate fortune, long life if not immortality, and interesting if ephemeral company. The King gets bait to gather tasty dinners. Relative to Cordyceps or even Toxoplasmosis, the King is pretty kind to Its host/partner, if not to his ability to form long-term relationships.

That feeding is subtler, too, than many predators. If people constantly drop dead around you, you’ll quickly become either a suspect or a little old lady detective. If your friends tend to be in ill health and die in their forties, that sort of bad luck—or bad choices—can happen to anyone. And Wagner would know: This story was published posthumously in 1995, Wagner himself having passed away in 1994 from heart and liver failure consequent to alcoholism.

Like Lovecraft, he must have been very aware of his own imminent mortality. And unfortunately, that kind of awareness doesn’t always result in “The Shadow Out of Time.”

Actually this reminds me more, thematically, of later Heinlein: writers writing about writers, and imagining immortality. Lovecraft’s particular power at that stage was the focus on legacy over long life. Though he sometimes depicted the inconceivable cost of living forever, he was far more obsessed with the inconceivable cost of being remembered—and that makes his last stories far more memorable.

Next week, a tale of Sword & Elder Sorcery in Jeremiah Tolbert’s “The Dreamers of Alamoi.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.