In the second century AD, the Roman writer Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis interrupted the winding plot of his novel, Metamorphoses, or The Golden Ass (a title used to distinguish the work from its predecessor, Ovid’s Metamorphoses) to tell the long story of Cupid and Psyche—long enough to fill a good 1/5 of the final, novel length work. The story tells of a beautiful maiden forced to marry a monster—only to lose him when she tries to discover his real identity.

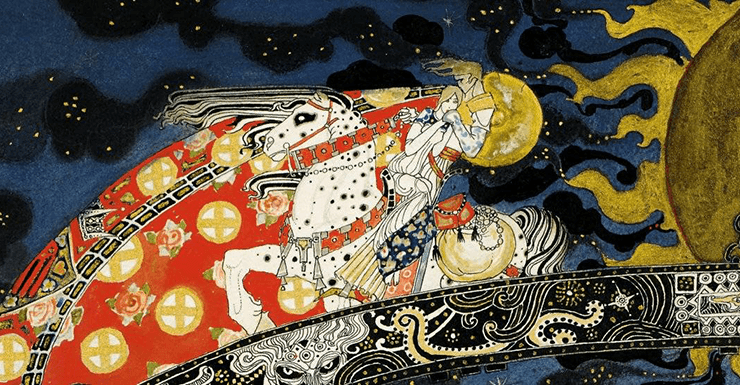

If this sounds familiar, it should: the story later served as one inspiration for the well-known “Beauty and the Beast,” where a beautiful girl must fall in love with and agree to marry a beast in order to break him from an enchantment. It also helped inspire the rather less well-known “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” where the beautiful girl marries a beast—and must go on a quest to save him.

I like this story much more.

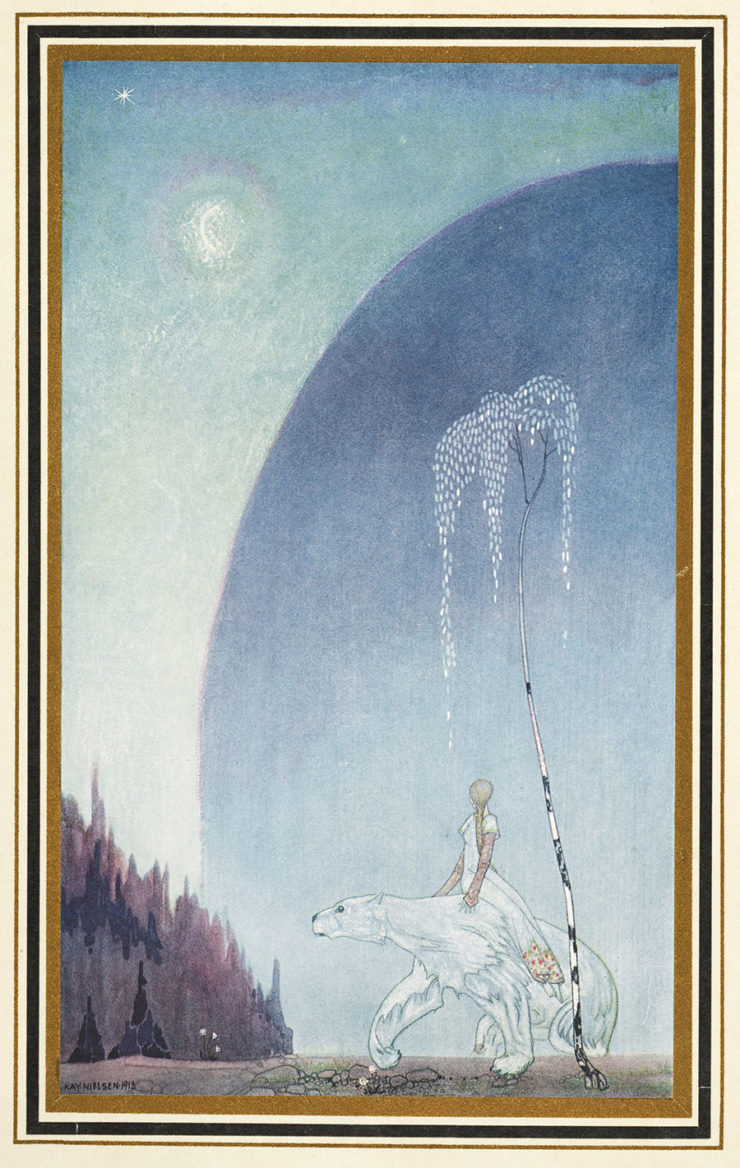

“East of the Sun, West of the Moon” was collected and published in 1845 by Norwegian folklorists Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Engebretsen Moe, and later collected by Andrew Lang in his The Blue Fairy Book (1889). Their tale beings with a white bear deciding to knock on the door of a poor but large family. So poor that when the bear asks for the youngest daughter, promising to give the family a fortune in return, the father’s response is not “Hell, no,” or even “Wait a minute. Is this bear talking?” or “Can I see a bank statement first?” but “Hmm, let me ask her.” The daughter, not surprisingly, says no, but after three days of lectures and guilt trips from her father, climbs up on the back of the bear, and heads north.

I must admit that when I first read this story, I missed all of the questionable bits, because I could only focus on one bit: she was getting to ride on a bear! Talk about awesome. And something easy enough for Small Me, who rarely even got to ride ponies, to get excited about.

Which was probably not the right reading. After all, in most of these tales, the youngest daughter bravely volunteers to go to the home of the monstrous beast—either to save her father (in most versions) or because she believes she deserves it, for offending the gods (the Cupid and Psyche version) or because an oracle said so (also the Cupid and Psyche version, featuring the typical classical motif of “easily misunderstood oracle.) This girl initially refuses. To be fair, she’s not under the orders of an oracle, and to be also fair, her father’s life isn’t at stake. What is at stake: money, and she does not want to be sold.

Nor can it exactly be comforting to learn that her parents are willing to turn her over to a bear—even a talking bear—for some quick cash.

But her parents need the money. So. In the far north, the girl and the bear enter a mountain, finding a castle within. I must admit, I’ve never quite looked at mountains the same way again: who knows what they might be hiding, underneath that snow. During the day, the girl explores the palace, and only has to ring for anything she might want.

And every night, a man comes to her in her bed—a man she never sees in the darkness.

Eventually, all of this gets lonely, and the girl wants to return home—thinking of her brothers and sisters. The bear allows her to leave—as long as she doesn’t talk to her mother. That, too, is a twist in the tale. In most versions, mothers are rarely mentioned: the dangers more usually come from the sisters, evil, jealous, concerned or all three.

In this version, the mother is very definitely on the concern side, convinced that her daughter’s husband is, in fact, a troll. A possibility that should have occurred to you when he showed up to your house as a talking bear, but let us move on. She tells her daughter to light a candle and look at her husband in the dark. Her daughter, having not studied enough classical literature to know what happened to her predecessor Psyche after she does just that, lights the candle, finding a handsome prince.

Who immediately tells her that if she had just waited a little longer, they would have been happy, but since she didn’t, he now must marry someone else—and go and live east of the sun and west of the moon.

This seems, to put it mildly, a bit harsh on everyone concerned. Including the someone else, very definitely getting a husband on the rebound, with a still very interested first wife. After all, to repeat, this version, unlike others, features a concerned mother, not evil sisters trying to stir up trouble. Nonetheless, the prince vanishes, leaving the girl, like Psyche, abandoned in the world, her magical palace vanished.

Like Psyche, the girl decides to search for help. This being an explicitly Christian version—even if the Christianity comes up a bit later in the tale—she does not exactly turn to goddesses for assistance. But she does find three elderly women, who give her magical items, and direct her to the winds. The North Wind is able to take her east of the sun and west of the moon. Deliberate or not, it’s a lovely callback to the Cupid and Psyche tale, where Zephyr, the West Wind, first took Psyche to Cupid.

Unlike Psyche, the girl does not have to complete three tasks. She does, however, trade her three magical gifts to the ugly false bride with the long nose, giving her three chances to spend the night with her husband. He, naturally, sleeps through most of this, but on the third night he finally figures out that just maybe his false wife is giving him a few sleeping potions, skips his nightly drink, and tells his first wife that she can save him if she’s willing to do some laundry.

No. Really.

That’s what he says: he has a shirt stained with three drops of tallow, and he will insist that he can only marry a woman who can remove the stains.

Trolls, as it happens, are not particularly gifted at laundry—to be fair, this is all way before modern spot removers and washing machines. The girl, however, comes from a poor family who presumably couldn’t afford to replace clothes all that often and therefore grew skilled at handwashing. Also, she has magic on her side. One dip, and the trolls are destroyed.

Buy the Book

Miranda in Milan

It’s a remarkably prosaic ending to a story of talking bears, talking winds, and talking…um, trolls. But I suppose it is at least easier than having to descend to the world of the dead, as Psyche does in one of her tasks, or needing to wear out three or seven pairs of iron shoes, as many of the girls in this tale are told they must do before regaining their husbands. In some ways, it’s reassuring to know that a prince can be saved by such common means.

In other ways, of course, the tale remains disturbing: the way that, after having to sacrifice herself for her family, the girl is then blamed for following her mother’s instructions—and forced to wander the world for years, hunting down her husband, and then forced to give up the magical golden items she’s gained on the journey just for a chance to speak to him. (The story does hurriedly tell us that she and the prince do end up with some gold in the end.)

But I can see why the tale so appealed to me as a child, and continues to appeal to me now: the chance to ride a talking bear, the hidden palace beneath a mountain, the chance to ride the North Wind to a place that cannot possibly exist, but does, where a prince is trapped by a troll. A prince who needs to be saved by a girl—who, indeed, can only be saved by a girl, a doing something that even not very magical me could do.

No wonder I sought out the other variants of this tale: “The Singing, Springing Lark,” collected by the Grimms, where the girl marries a lion, not a bear, and must follow a trail of blood, and get help from the sun, the moon, and the winds, and trade her magical dress for a chance to speak with the prince; “The Enchanted Pig,” a Romanian tale collected by Andrew Lang, where the girl marries a pig, not a bear, and must wear out three pairs of iron shoes and an iron staff, and rescue her prince with a ladder formed from chicken bones; “The Black Bull of Norroway,” a Scottish variant where the girl almost marries a bull, and can only flee from a valley of glass after iron shoes are nailed to her feet; “The Feather of Finist the Falcon,” a Russian variant where the girl must also wear out iron shoes in order to find her falcon—and her love.

These are brutal tales, yes, but ones that allowed the girls to have adventures, to do the rescuing, and to speak with animals and stars and winds and the sun and the moon. Among my very favorite fairy tales.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.