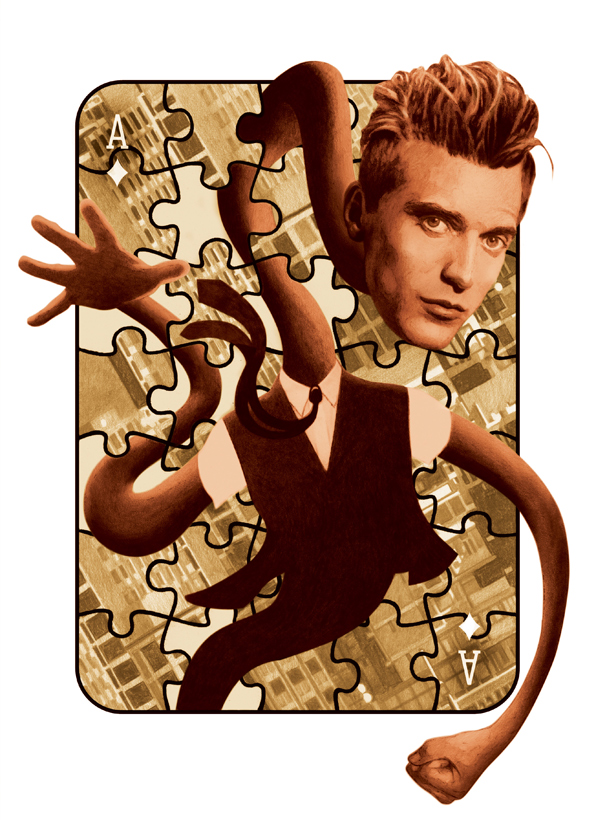

For over 25 years, the Wild Cards universe has been entertaining readers with stories of superpowered people in an alternate history. “Fitting In” by Max Gladstone shows how everyday people can step up to become extraordinary.

Robin Ruttiger tries—he really does—but his lot in life falls way shorter than his expectations. A failed contestant of the superhero reality TV show, American Hero, he now works as a high school guidance counselor to reluctant students. Things change, however, when a favorite bakery in Jokertown becomes a target of vandalism, and Robin realizes he can play the hero after all.

Six weeks into the school year, Robin Ruttiger still didn’t feel like he belonged in Jokertown.

The commute was part of his problem, he knew. He’d rented a sterile flat up in East Harlem, and the 6 south from 116th Street was a mess. Robin’s elastic powers could have helped with the crush, in theory, but going into full Rubberband mode on public transit wasn’t as good an idea as it might sound. Yes, he could squeeze himself paper thin, stretch his arms to whips and wrap them around the bar overhead, but it made his neighbors nervous. Plus, the one time he’d tried, he’d tangled himself up, and his pants fell down.

Anyway, if he started stretching in public people might recognize him from TV. It had been five years since he competed on the second season of American Hero, trying to win the dubious honor of America’s favorite spandexed good-doer, but even though he’d never cared for the celebrity circuit he’d had a few more rounds on the tabloids and talk shows than his fellow contestants, between coming out, breaking up with Terrell, and leaving the spotlight to get his master’s in education. He’d slipped incognito through grad school, but the last thing he needed was some blurry cell phone video on BuzzFeed drawing another round of the same old questions.

So he woke up at four most days in his blank apartment, dressed and packed in the dark, rattled on the train with his backpack jammed between his legs and a paperback in hand, then walked again from Lafayette to Xavier Desmond High. He waved to the night custodian as she got off shift, and slunk down narrow waxy halls to the cramped office with GUIDANCE COUNSELOR on the door, ROBIN RUTTIGER on the desk, and the last occupant’s kitten poster still on the wall: hang in there.

The last counselor obviously hadn’t.

Buy the Book

Fitting In

In just six weeks, a pile of paperwork had overwhelmed not only his inbox but the notion of pile, splaying and slipping and tumbling until it was more of a mound. He finished as much as he could before the starting bell, without making any visible progress.

In through the nose, and out through the mouth, was what the two-dollar mindfulness book he’d bought at the Strand advised. Life comes one breath at a time. His first-period meeting didn’t show. He breathed out, and wrote an absence slip.

Robin had better uses for the forty-five minutes, anyway. He still had to enter comments on kids he’d met into the student database. He’d turned off autocomplete on his laptop four times, but each time it turned itself back on. When he typed u it suggested unresponsive. S was for silent, sometimes sullen. He deleted that one every time it appeared. C, cautious.

At last, the bell rang, and the break before second period set him free.

The world might hold greater joys than the walk across Roosevelt Park to Zargoza Bakery in early autumn, but Robin couldn’t afford them these days. Clear sunlight through yellow-red leaves dappled the green. A tinkertoy contraption with a child’s face scuffed its many feet through a leaf pile; in the trees overhead, three small folks hunted squirrels with six-inch spears. Not exactly an Ohio autumn. He looked both ways before he crossed the street. A half-man, half-bus individual trundled to the curb and disgorged—no, make that released, the individual in question had a mouth, which gave the other term even more unfortunate implications than usual—a small parade of absolutely identical women in absolutely identical black hats. Sisters? Twins? One person split into many bodies, or experiencing the same moment many different ways in time?

Robin realized he was staring, and stopped, and walked faster. Zargoza’s was his daily indulgence—a fardelejo, coffee that hadn’t come from the break room’s foul pod machine, and a brief spot of warmth. Then back out into the world. The second-period break was short, but he’d timed his trip exactly. If he walked fast he’d make it back for the bell.

When he reached the Zargoza Bakery there was a line out the door, and the line was not moving.

A line wasn’t unusual in itself. There were often lines in front of Zargoza’s. There had been since before Jetboy back in ’46, before the plague, before the riots and the barricades and the aliens. Through all that Mama Zargoza kept the doors open and the pastries and coffee served and the gold leaf filigree window her papa’d bought in 1927 shining and clean. The lines had been longer than ever in the week before Mama Zargoza’s funeral, and there had been lines every day since her granddaughter Octavia took over.

But the line always moved.

Octavia kept it moving. Octavia, caked in flour, hair straining against its kerchief, deep-dimpled and smiling, her arms heavy from kneading dough, at the center of her swarms of little animated doughmen, could greet her customers, serve them in thirty seconds, and usher them out the door feeling like they’d had a half-hour conversation. Robin and Octavia had never met outside of work—they were both busy enough that “outside work” had little meaning—but she was an old Motown fan, and so was he, and she didn’t watch television, so he never had to worry that she might one day remember how he looked wearing red spandex and a stupid little cape.

But this line wasn’t just not moving—it was growing. An oak tree in a peacoat shifted from root to root and breathed into her hands. Robin joined behind a tall, thin, eyeless man in thick mittens and a coarse knit scarf who appeared to be reading the standard-print Wall Street Journal. Robin tried to wait. He glanced at his watch. It still wasn’t working. He kept meaning to change the battery, but by the time his after-school meetings were done all the shops were closed, and he had to get to the office before they opened. He checked his cell phone instead. Ten minutes until next period. He shouldered deeper into his threadbare coat. “What’s going on?”

“Eh, who knows.” The eyeless man had a thick Long Island accent.

“I heard shouting,” the oak tree offered.

The eyeless man shrugged and turned the page to the stock report. “Not our problem, is it?”

He looked to Robin for reassurance, but Robin was already weaving to the front of the line.

Robin grabbed his belt to keep his pants from slipping down around his ankles, made himself skinny, and slid past the oak tree and the animated mannequin in front of her. With a sigh, he corkscrewed between the legs of the conjoined triplets who blocked the door. Inside, the bakery was cramped even worse than the 6 at rush hour; here, though, he didn’t feel as awkward about stretching himself nine feet tall and ribbon-thin and squeaking past tight-packed bodies to the front of the crowd, and the raised voices.

“I’m not selling, Mikhail,” Octavia was telling a tall broad man in a black suit, with all her voice’s usual strength and none of its usual welcome. “Not to anyone, and certainly not to you.” It was hard to tell what of the cracked flour on her arms was just flour and what was the doughlike skin she’d gained when her card turned. Coils of hair had escaped from her kerchief. Octavia’s card let her shape little helper homunculi from dough, tiny half-cute, half-creepy helpers who communicated by purring and tended to anticipate her needs. Normally they swarmed through the kitchen, kneading and turning and minding the ovens, but now a pile of them gathered on the countertop to glare at Mikhail with their cinnamon drop eyes.

“Is good offer,” Mikhail said. “Honest, and generous.”

“You’ve come here every week for a month and every time I say no, and you don’t listen. You’re holding up my customers. Will you please just leave me alone?”

Mikhail adjusted his shoulders, which took a lot of adjusting, since there was a lot of shoulder. He set one knuckle to his chin, pondering, and did not leave.

Robin had been a hero for a while. He’d been bad at most of it except for the cats-out-of-trees part (cats liked him, probably because they knew he was allergic), but he’d stopped a few robberies and made it onto TV and toured the country and even dated Terrell who was a real true-blue hero, one of those rare guys who had the knack of saying the right thing and meaning it. But he was past all that now. He was a guidance counselor at Xavier Desmond High School, and while he had always believed that teachers were the real heroes, this sort of thing wasn’t in his job description anymore. He knew from his hero days how often well-intentioned intervention made things worse. Octavia could handle herself. She really could.

Still, he found himself tapping Mikhail on the arm and saying, “Um. Excuse me? Is there a problem?”

Mikhail turned around. Like the shoulder-adjusting, that took a while, and for the same reason. He looked down his nose at Robin, which was a nice trick since he was actually a couple inches shorter—but this guy had down-the-nose practice, not to mention a solid foot of breadth on Robin. The effect would have been intimidating if Robin hadn’t spent years dating a man who warmed up for his bench press by chaining a Buick to each end of the bar. “Is no problem. Civil discussion only.”

“Robin,” Octavia said, calm, measured. “It’s okay.”

He took the hint. God, he felt stupid. What did he mean to do, anyway? Start a fight with this guy, smash a few tables and the little pottery tchotchke cats Mama Zargoza’d spent her life collecting—maybe even that beautiful window? Make more trouble for Octavia? “Sure. Sorry. I don’t want any trouble.”

“Is no trouble at all,” Mikhail said, drawing closer, and Robin’s hero hindbrain started calculating exits and trajectories in case this got ugly. “Is all business. You should explain to lady friend. Is always good to do business.” Mikhail wasn’t about to punch Robin—was he? With all these people watching? Or was he trying to goad Robin into trying something? Robin felt so jumpy it just might work.

Robin opened his mouth without knowing what he was going to say. His throat was dry, and his voice croaked. Then there came a flash, and he was blinded.

Lightning, he thought first, and then, Camera. When he blinked the spots from his vision, he saw Mikhail had rounded on the photographer: an Asian woman a bit older than Robin, wearing a leather jacket and leather trousers, all buckles and studs, leather gloves, comically huge sunglasses. Electric blue lines webbed her skin, and she was grinning as she looked down at her camera. “Wow! Never got a snap of a reptoid agent in the wild before. Usually you’re more the shadows-and-secrecy type.”

“Give me that.” Mikhail grabbed for the camera, but the woman stepped back without looking as if she’d noticed.

“Or are you Illuminati? Bavarian or Alsatian? Then of course there’s the counter-Rosicrucians, considering the accent.” She raised the camera and snapped another picture, another blinding flash. Mikhail covered his face too late. He sputtered.

“Get back here. I am not—what is reptoid?”

“Precisely what a reptoid would say. Go tell your lizard masters to stay out of Jokertown!”

Mikhail lumbered toward her, swiping blindly, but Octavia caught his wrist. He swiveled toward her, slow and dangerous, but Octavia didn’t give. “Mikhail. I think you should leave.”

Mikhail glared at her. He tried to pull his arm out of her grip, but Octavia had kneading muscles. And in the pause that followed, Mikhail heard the murmurs.

Crowds, in Robin’s experience, were funny, changeable things. Groups of people played little games together without realizing it. When the whole group watched in silence, they were playing ‘audience’: the audience doesn’t speak up, doesn’t interfere. You could shout orders to a crowd in an emergency and they’d just blink. They weren’t part of the scene—they were supposed to watch. But if a few people left the audience and started doing something, well, the rest of the audience might start to ask themselves why they weren’t doing things too. They put aside the game of audience and started playing other games: work group, army, mob.

More people had crowded into the bakery. The oak tree cracked her knuckles. The triplets glared with six eyes between them. Even the eyeless gent had rolled his copy of the Wall Street Journal into something like a club.

Mikhail looked from the crowd, to the photographer, to Robin, to Octavia. He frowned with his forehead. “Very well. No business today.” She let him go. He tried to wipe away the flour she’d left on his sleeve, and mostly did. “But you will understand in time.” When he straightened his lapels, the flour on his palm dusted one of them white. He turned to go. The crowd parted grudgingly. Halfway to the door, he tripped. When he recovered his balance he glared at the crowd, but everyone looked innocent, especially the triplets. He squeezed past the oak tree and the eyeless man, and glowered off up the street.

“Here you go, Robin.” He turned to see a doughboy set a fresh fardelejo in wax paper on the counter beside a cup of deep black coffee in a cardboard sleeve. Octavia smiled. He’d never seen her smile as a mask before. “On the house.”

“Octavia, I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have butted in.” He reached for his wallet, and had it halfway open when she put her hand over his to ease it closed.

“I’m glad you did. I can handle myself, but you and Jan helped.” He looked around for Jan—the photographer, he assumed—but she’d vanished into the crowd. “Real estate guys get worse all the time. Even Jokertown’s Manhattan these days.” Her smile tightened. “How’s the guidance, counselor?”

He took the hint. “Another no-show this morning. Starting to wonder if they’ll ever trust me.”

“You’ll be all right.” This time the smile was close to real. “This is Jokertown. Trust takes time. The kids will open up.”

Ten minutes, a coffee scald, and a school bell later, Robin sat across his office desk from a big slab of a kid named Slade, with rock-hard skin and heavy opal eyes, as closed as a sarcophagus. Slade held his hands cupped in his lap, and made slight grinding sounds when he moved.

Robin glanced down at the file again, at circled words: underperforming, risk, attention issues, disengaged. Detentions for weeks. Arrested once for shoplifting, but the store owner didn’t press charges.

The books he liked said you weren’t supposed to tell the student about themselves. You might get it wrong, or worse, get it right in a way that hurt. He wasn’t here to read Slade’s profile back to him. Slade’s card turned young, and since then he’d always been the big dumb rock guy, a useful buddy to have in grade school—his friends didn’t expect anything more from him than backup. Teachers wrote him off, even joker teachers who should have known better. Even at Xavier Desmond, which had a football team the way some people have plantar’s warts, the coach followed him with the kind of attention usually reserved by hyenas for small wounded buffalo. The last thing Slade needed was one more person telling him who he was. But that left Robin sitting across the desk, waiting for him to talk.

He reached for his coffee. It was empty. He’d finished it in the first silent minutes of the session.

“What do you like to do outside of school?”

Slade raised his head with a sound like heavy tires crushing gravel. “Nothing. Hang out.”

Robin waited for him to elaborate. Slade waited for him to ask another question. Slade won.

“Ms. LaJolla enjoyed teaching you geometry.” He didn’t mention the incomplete portfolio note, or refuses to answer questions in class. “Do you like math?”

Slade’s eyes rolled up to Robin’s face, then down again. “I guess it’s okay.”

After forty more minutes of that, Robin saw Slade to his office door, drifted to the teachers’ lounge, and collapsed in an understuffed, coffee-stained chair, staring at the wall. Hang in there. He wondered why he’d thought of that, then realized he was staring at another cat poster. They were the same, but this cat looked closer to falling.

Ms. LaJolla marched into the room, checked her mailbox, flipped through the papers stacked there, shredded five of them, and tossed the rest into the trash. Robin heard the shredder growl. He needed sleep. He checked the clock. Five minutes to the next period. He checked the clock again. Still five.

Ms. LaJolla stopped at the door and turned back to face him. They’d traded maybe ten words since Robin started at Xavier Desmond, and he didn’t know much about her other than that other math teachers shivered when she drew near. Beatrice LaJolla ruled Geometry with an iron fist. Rumor had it that once, when some parents came in to protest their kid’s grade, she’d given the parents homework.

“You’ll toughen up,” she said. “My first six weeks, I cried myself to sleep every night.”

The door slammed behind her.

Robin left after sunset and eight more pointless all-but-silent meetings, and shouldered deep into his coat as he crossed the park. The sky dimmed starless overhead. He had too many thoughts about himself and his life choices, but he also had a personal rule about taking seriously any self-criticism that arose on his homeward commute. Even in his young career as a guidance counselor, though, he’d learned that just because you knew better than to do something, didn’t mean that you could stop. Streetlights and headlights cut the dark but did not relieve it.

Zargoza’s should still be open. Octavia made this thick drinking chocolate, what she said was European style, which bloomed on the tongue as rich as any wine. Robin could not afford two café visits in a day, but she’d given him the pastry and coffee free this morning, and it wasn’t like he could afford anything in this city on a teacher’s salary. Chocolate might not justify God’s ways to man in any lasting sense, but it did fine over short distances.

He’d just turned off Roosevelt when he saw the crowd, and the police lights.

His ever-unhelpful hero brain salted panic with analysis as he ran toward the crowd. No flames, that was a good start. No ambulance, either: probably also good. Unless it was so bad they’d told the ambulance not to hurry.

He stretched his legs fourteen feet high and lurched over the crowd’s heads with a single teetering stride. His legs sprang back to more-or-less normal with that trademark rubber-band snap, and sent him sprawling to the sidewalk in front of Zargoza’s, one hand on asphalt, the other in a pile of broken glass.

He sat up and shook the glass off. Most of it fell away, but one long triangular shard had actually pierced him, and when he pulled it from his palm the pale hydraulic fluid he had instead of blood these days leaked out and congealed into a translucent lump. It hurt, but he didn’t care at first. The shard of glass was covered in trailing gold leaf filigree, and printed with the lower corner of a Z.

The shop was dark. Slivers of the gleaming 1927 window hung from the frame like broken teeth. Most of the glass lay shattered on the ground.

“Sir! Sir, I’ll have to ask you to step back.”

He looked past the policewoman to Octavia, who stood, shaking, blanket around her shoulders, beside another cop. Doughboys huddled against her ankles, flaking in the chill. Jan, the photographer from before, was offering Octavia a cup of something hot, but Octavia hadn’t noticed—because she had seen Robin, and, in spite of the broken window, in spite of everything, she looked relieved.

“It’s okay,” he told the cop. “I’m a friend.”

Heroes tended to meet people on very bad days. Though Robin never told the magazines, that was one of the reasons he quit—he wanted to help people before things got so bad you needed powers to do it.

Octavia held herself together better than most. Robin and Jan talked her into a cab, doughboys clustered in her lap, and rode with her to her building, which would have been twenty minutes’ walk away. She made it up five flights of stairs and through her triple-locked door into a sidewalk rescue chair whose ragged upholstery she’d covered with a knit blanket, before she started crying. Robin touched her shoulder. She did not seem to notice. He shot Jan a what-should-we-do-now look, but she raised her hands, search me, and retreated to Octavia’s postage stamp kitchen to start a kettle boiling. Robin looked around the cramped apartment, every surface that wasn’t a counter covered in bright cloth, and after some doily-displacing scramble, found a box of Kleenex wearing what seemed to be a specially knit wool jumper. Octavia took a tissue, blew her nose, and said, “Thank you,” and, “I’m just so angry!”

He hadn’t expected the last word, so the reply he’d had ready, “It’s okay,” sounded wrong. The doughboys glared at him, confused. “I mean. It’s not.”

“No! It’s not. It is not okay.” She pronounced every word distinctly. “My great-grandfather bought that window. What is even happening to this city? Mama Z got robbed a couple times in the eighties when things were really bad, but they’re supposed to be better now, and the last two months—what’s wrong with people?”

He thought of Mikhail, and of the crowd. “Did you see who did it?”

“Some kids in tracksuits and masks. Not jokers that I could tell, but you can’t always.” Her hands were dry and their dough-skin was cracking. She reached without looking for a moisturizer jar among the plants on the side table, unscrewed the lid, and massaged the white cream into her palms. “I bet they’re the ones who spray painted my shop two weeks ago—all those horrible words, I was up all night cleaning them off. Maybe they blew out the tires on my delivery truck, too. Detective McTate—thank you, Jan—he said they’ve had reports of people lingering around. Loitering. The police always think people are loitering in Jokertown, but…” She sipped her tea instead of finishing her sentence. Robin looked from her to Jan, who’d crossed her arms and leaned back against the overstuffed sofa. She still wore her sunglasses.

“You know it’s not kids,” Jan said.

Octavia blew her nose long and loud, and handed the crumpled tissue to one of her doughboys. They tossed the ball of paper from one to the other to the trash can hidden under the spider plant. She laughed. “Maybe they just don’t like me. They liked Mama, but I’m not Mama.”

Seated mute across from her, Robin remembered the urgency with which Octavia had said, It takes time. Had she been talking to herself as much as to him? Absurd. People loved Octavia. Mrs. Blaine in the history department, who’d moved to Jokertown when she grew gills forty years ago, always said how happy she was Octavia was following in her grandmother’s footsteps. Though now it occurred to him to think more closely, Mrs. Blaine had sounded surprised. “It’s not you,” he said. “It’s them. And it’s not even them, probably. The attacks on your business, Mikhail trying to buy you out—it’s too close for coincidence.”

“Exactly,” Jan said. She stood up and started to pace, gesturing wildly. “There’s a dark truth at the bottom of this. Wheels within wheels. But we’ll drag the skeleton out of the closet.”

“Really?” Octavia looked shocked but relieved. Robin had seen that effect before. People didn’t like to think that the world might just hurt them for no reason, but the suggestion of conspiracy could coat disasters with an oil slick of order.

He stretched out his hand to take Octavia’s wrist. “I wouldn’t be surprised if Mikhail’s trying to push you away from your shop. Don’t worry, though. Whatever’s happening, we’ll find out, and stop it.” He glanced up to Jan, who shrugged, sure.

“I can’t ask you to do that for me,” Octavia said.

“You’re not asking.”

She put down the tea and hugged him. Doughboys rained from her lap at the sudden movement, and landed with a somersault on the rug. “Robin. Jan. Thank you. But it’s dangerous. It means so much that you’d offer, but really, I mean, shouldn’t you go to the police?”

“I already told them what I think,” Jan said. “They might listen, or not. Either way, they have their own idea, which is that a joker gang is running around picking on small business owners. Cops look for cop-sized solutions to cop-sized problems. If we push them on it, maybe they’ll run in a few XD students who just happen to be hanging around school at night. Robin, how many of your kids do you think could get arrested without being booked for resisting? How many of their families can afford bail?”

Robin hadn’t even thought of that part. Some guidance counselor he was.

“Besides,” Jan said. “Robin’s a hero. We’ll be fine.”

Jan walked fast. She was inches shorter than Robin, but he still had to stretch his legs and quicken his step to match her pace. “Look, Jan—”

“Jan Chang.” She turned, grabbed his hand, and squeezed without breaking stride. Her handshake gave him a tingling static feeling even through her gloves. “And you’re Robin Ruttiger. I watched your show before I blew up my television. Got halfway through. Did you win?”

“What? No.”

“Glad to have you on board anyway.” She stepped off the sidewalk, still walking backward, just as the light turned green. He shot out his arm into a long rubber rope to pull her back, but the oncoming cab squealed to a stop inches from her leg. Jan glanced at Robin’s arm over her glasses, intrigued, while the cabbie cursed. “That was nice of you.” She turned to face front and kept walking.

“I think we’re on the same page about what’s going on here, with Octavia’s shop and with the tracksuits and with Mikhail, but I want to be sure.”

“Yeah.” She walked through a cordon into a street festival that had closed off a block of Mulberry. Kids clustered around a fried dough stand; a cold but enthusiastic band of Brooklynesque young people with strange facial hair played polka music. Robin waved to a man he recognized selling arepas. “It’s reptoids,” Jan said. “Obviously.”

“What? What’s a reptoid?”

“Secret lizard inhabitants of the counter-Earth. Or possibly they occupy our own planet’s hollow core. I’m not sure yet. I’ve been tracking them for a while. They infiltrate surface society with their mind control and shape-shifting powers.”

“What? I’ve never heard of anything like that.”

“Of course not. Do you think ancient superintelligent shape-shifting mind-control lizard monsters would be so bad at this that you would know about them?”

He frowned. “Is this where you start talking about the Rothschilds? Because if so, I can solve this case on my own, thanks.”

“Ugh. I know we’ve just met, and trust me I understand where the question’s coming from, there’s a ton of anti-Semitism in the field of Secret-World-Men-Behind-the-Curtain Studies and it’s gross and evil and those of us who are really trying to save the world always need to be on watch against it. But please believe me, and do keep calling me on this if you think I’m screwing up: I’m not talking about racist scapegoat fantasies. I’m talking about real actual lizard people.”

He tried to follow her logic, and ended up feeling like a yoga victim. “I do think it’s Mikhail, though. He wants the shop. Real estate in Jokertown’s still cheaper than most other places in Manhattan, but not for long. He wants to get in while the getting’s good, but Octavia won’t sell. So he’s trying to force her out.”

“Because,” Jan said as if spelling things out for a child, “his reptoid masters want to expand their secret network of mind-control broadcast stations. They’ve had trouble in New York because the real estate prices are so high. But Zargoza’s is a good target, and it’s located on a nexus of the geomantic power their technology requires.”

Was she crazy? You weren’t supposed to call people crazy. But he was pretty sure none of the things she was saying were actually things. She seemed to be a friend of Octavia’s, and Jokertown was full of its own sort of people, but none of this seemed helpful. “Look, I’m not saying Mikhail’s a nice guy, but he really doesn’t seem the mind-control conspiracy type.”

“Which is—”

“—exactly why he’d make a perfect reptoid agent?” he suggested.

She stopped, wheeled on him, and shifted her glasses down her nose. Her eyes were bright blue without pupils, and glowed softly from within. The little veins around her irises were blue, too, and pulsed. He tried not to look away. On the show, he always looked guilty when he was being judged. Blame it on the Catholicism. “I like you, Ruttiger. Even if you are a bit naïve.”

She shouldered past two men selling watches onto Prince toward Bowery, then north. “All I’m saying is, we don’t need a more complicated explanation when we have a simpler one.”

He didn’t need to see her eyes to tell she was rolling them. “What are you, William of Occam?”

“No! I’m just trying to figure this thing out. If all the stuff you’re talking about was real, I mean, really really real, we’d have to plan for it. I don’t even know how you defend against, what were you saying, reptoid mind control.”

Right on Houston, across the park, then south on Forsyth past the school. “Nobody’s sure. That’s what makes it so dangerous. Some people go for gemstones. I think leather insulates you. Their technology’s designed to exploit thin mammalian skins.”

“But if it’s really just that Mikhail hired some thugs to intimidate Octavia into selling, then all we need to do is link Mikhail and the thugs.”

“And if we go in unprepared, the reptoids will eat us for dinner. They do that, you know. I mean, I bet they don’t call it dinner, lizards would have a whole different way of thinking about meals. Slower metabolisms. But you get the idea.”

She turned left onto Eldridge. Robin added up the turns in his head, frowned, and quickened his pace to walk beside her. “Couldn’t we have just crossed at Kenmare?”

Jan raised one eyebrow. “God, Ruttiger, haven’t you ever shaken a tail before?”

He hadn’t seen anyone, or at least, he didn’t think he had seen anyone. “Are we being followed?”

“Not that I can see. But if they were good at their jobs, I couldn’t. So it’s better to assume. Come on. We’re almost there.”

If not for the virus, this row of apartment buildings would have gone through at least two rounds of gentrification by now. The building on the corner was a broken-windowed mess; so was the next, though one of the tenants had tried to make it a bit more homey with the addition of a bright yellow welcome mat and fake plastic flowers. The tenant in question was wearing a Tommy Bahama shirt, and collecting his mail, and appeared to be a more or less ambulatory walrus. He waved. “Hi Jan!”

“Hey Jube!” She stopped two doors down, in front of the most broken building on the street—chunks of brick missing from the façade, rusted iron on the rails. Little stone lions flanked the front steps. At least, one of them was a lion. The other was missing its head.

“What we need,” Robin said, “is a—”

“Stakeout,” Jan said at the same time as he did. “Exactly. Whether this is a random attack or reptoids or a conspiracy, someone might come back tonight to follow up. Maybe they’ll hold off until Mikhail can approach Octavia again—but if we’re lucky they’ll come and we can trace them back to their hideout. So we need gear, in case they’re ready for us. Or in case they’ve mobilized a short-range mind-control device. I’ve developed a range of anti-reptoid paraphernalia in collaboration with key researchers on the internet. It should keep us safe. I’ll be right back.”

She vaulted over the railing, landed on the basement level, and forced the door open with her shoulder. A startled rooster—less startled than Robin felt seeing a rooster in Manhattan—ran outside, bucking protest. From within, Robin heard a curse, crashing paint cans, grinding glass, a heavy whuff of falling paper, a second curse, and two loud bangs he was reasonably certain weren’t gunshots. Jan Chang staggered out ten minutes later laden with duffel bags, slammed the door with her foot, and tossed one of the duffel bags to Robin. The weight started to bowl him over, but he shot one arm twenty feet up to wind around a lamppost and kept himself more or less afoot. Jan threw her own duffel over the rail onto the sidewalk, and vaulted after. “Great.”

“What is this dump?” Robin’s arm did not want to unwind from the lamppost at first, but when he tugged harder it slipped free with a snap. “Secret hideout?”

“More or less,” Jan said. “It’s my home. Come on. We have a stakeout.”

“What I don’t get,” Robin said later, in the car down the street and across from Zargoza’s Bakery, “is, if there really were lizard people with immense technological powers, why would they care about controlling our world? Why not just…do their own thing?”

“Maybe they’re afraid.” She unscrewed her tea thermos lid and drank. She’d offered Robin some, but it tasted smoky and weird, which she claimed it was supposed to. Robin’s experience of tea was limited to Lipton and Lemon Zinger, so maybe she was right. “Maybe they think we might go to war if we discover them, and they don’t want to kill us. What I think is, they use humanity as a research experiment and nature preserve. They control us to keep us from realizing that there really is alien life out there in the cosmos.”

“There is, though.”

She laughed, and screwed the thermos cap on again.

“No, seriously. Aliens made the wild card virus. Doctor Tachyon was an alien.”

“Whose word do you have for that? An alien who just happens to look like a human being in Ren Faire garb wearing a silly hat? Come on, Ruttiger, I thought you were smart. It’s obviously a psy-op. And look how effective! There are all these pictures of him standing right next to normal humans and you can’t tell the difference except for the hat, and you still think he was from Mars or whatever.”

“There was an alien invasion back in eighty-six. The Swarm…”

“That’s just what they want you to believe. Obviously the invasion was staged. They don’t even need rubber suits these days. They can do it all with computers, or with cards.”

“But—wait. Why? Say your reptoids exist and really did want to use us as a nature preserve or whatever. Say they did want to keep us all to themselves. Why would they fake first contact, and an alien invasion, and an alien scientist living among us for fifty years? Why would they make it all up?”

“To see how we’d react, of course. But I think they’ll change their experiment soon. Don’t be surprised if you start to forget the aliens.”

“Why?”

“It’s failed, you see. The reptoids didn’t learn what would really happen if we met whatever’s out there.” She pointed up with her thermos, past the windshield, past the streetlights, past the slate-gray sky. “Think about it. You believe everything they’ve told you. Tachyon, the virus, interstellar criminal syndicates, the whole line. You’ve been sitting here listening to me, convinced I’m crazy.”

“I don’t—”

“It’s okay. I get that a lot. But, just for a second, stop thinking about me, and consider what’s going on in your own head.”

“Okay.” He knew he sounded skeptical.

“You don’t actually believe we’ve met aliens.”

“I do, though.”

“You don’t. None of you do. I’ve seen you around the last few weeks, Ruttiger. You go to work every day, you get your coffee, you worry about your rent and your, I don’t know, do you call them students? You worry about whether that sweater vest goes with those shoes, and the size of your bank account. If you believed aliens were real, really really real—if you believed that up there beyond the sky there really were other beings from other worlds, vast and maybe incomprehensible but certainly different from us, and that all this horrible nonsense we have down here was just one tiny thread of a huge tapestry, how could you stay so small? How could any of us fight about taxes, about oil, about the price of credit default swaps or who our neighbor fucks or what words she says when she prays? How broken would someone have to be, to know all that and not to change her life?”

He leaned his head against the window and gazed aimless toward the shop, toward the last glinting shards of broken glass that still clung to the frame. Police tape crossed and crossed again. If there were cops watching, he hadn’t seen them. Then again, maybe they were better at this than he was. She was wrong. He knew the truth. He’d seen pictures, and anyway who could possibly manage that kind of cover-up? Who had the resources? Who would dare try? But she was right about the other thing. He didn’t act as if he knew. Nobody did.

“What are you doing here, Jan?”

“I want to solve this case. Octavia’s a decent person. I’d like to stop the world from fucking with her, if I can.”

“I don’t mean here, now.” But he almost did. “I mean, in Jokertown.”

“You think I could live anywhere else?” She clunked the thermos back in the cup holder. “They’d lock me up. They’d lock any of us up.”

“You could pretend.”

“Too much of that going around.” She gripped the steering wheel. He saw a road roll on before her, long, straight, endless, and unpeopled, a road where she could drive forever and ever and never crash. She uncurled her fingers one by one. “I came down here when my dad died and my card turned. I was messed up. It took me a long time to sort things out.”

He said “I’m sorry” by reflex and in the silence after he wished he hadn’t, because even if the reflex was right, there was a wrongness to just saying the words without taking time to find the heart behind them. He should have waited and thought about who Jan might have been, who her father was, what turning her card would have done to her life, about how she’d come down here and how she’d ended up in a hole beneath a crumbling building. But she nodded as if he’d said the right thing, and maybe he had.

“I like it down here. My family used to live here, like Octavia’s—they left while Octavia’s grandma stayed. We never knew each other, but that’s kind of a connection. Besides, she makes good coffee. And her family history in the area makes me reasonably confident she’s not a reptoid agent.”

The world weighed so many million pounds and most of them were pressing down on Robin’s head and shoulders. The window glass felt cool against his temple. Maybe he should have drunk more of that tea, even if it didn’t taste like Lemon Zinger. “Of course,” was the best he could do.

“What about you, Ruttiger? What brings you down down to Jokertown?”

The first instinct was to answer I don’t know, but he did know. Didn’t he? He’d given all those interviews, though he’d never mentioned Jokertown, because if he had the spotlight would have followed him, as no doubt it would find him again someday when some kid scraping along through her tabloid internship by stapling together a TaskRabbit gig and a rideshare gig and a side hustle drawing porny fan art asked herself whatever became of…and pitched the story to her boss. He had reasons. He thought he had. He had some vague notion of giving back to “the community,” less certainty than ever what “the community” might be, and in the years since American Hero he’d had a growing sense that his life looked less like heroism and more like celebrity with every column inch or TV interview. Not everyone felt that way—Terrell hadn’t—but what everyone felt and what everyone did wasn’t Robin’s responsibility. He only answered to Robin Ruttiger. Not even to Terrell, these days. And didn’t heroism always tend to celebrity over time? To be a hero was to be a face, a personality, a brand. People liked you because of what you did at first, and then they liked you because you were you. Which was where it all got complicated. Heroes didn’t change anything.

And what made you a hero, or a villain? You got sick, or in Robin’s case a mad scientist injected you with a mutated virus strain to see what would happen, and you got better or you got dead. Even if you got better, mostly you changed in some way that didn’t help. Your eyes disappeared, wheels replaced your feet, you grew chitin plates all over your body. Your flesh turned to stone. And for the rest of your life you were the stone guy, or the girl with the chitin face, or the woman who turned into a wolf when she heard a bell ring.

And if you were one of the vanishingly lucky, like Robin, who had some marginally useful gift and could pass undetected in a crowd, well, when people found out that you could stretch your body like a rubber band, or fly, or move things with your mind, or deadlift a train, or turn invisible, they stopped caring whether you wanted to play the violin or teach high school or be a pharmacist. If you wanted to turn invisible for the rest of your life, or be a professional move-things-with-your-mind person, you were in luck, best wishes, enjoy the run. But if you didn’t…

The world was really good at deciding who you were without consulting you.

To be fair, the card often turned in ways that echoed your own personal damage. Sometimes it was a sick joke and sometimes it was a gift, which was what made the whole thing feel so mean. But whatever you became when your card turned, it wasn’t all about you. It couldn’t be. People weren’t just one thing. Not even heroes.

Once the card and the world decided who you were, the world tried so hard to use you. It had been easy to hide his graduate school plans from the talk shows and the magazines, because they weren’t interested. They couldn’t imagine him wanting to be anything but the stretchy guy. If he’d never left, he would have lived well and never realized he wasn’t free. But what about Slade, whose eyes made sounds like marbles rolling when they moved? God forbid the kid ever step into a military recruiter’s office to ask for directions. And there was always the other side of it: say he goes for a walk uptown one afternoon, or worse, out with his family to some small town where they don’t see jokers hardly ever, and there’s a cop. And.

He tried to explain all this to Jan Chang in the car across the street from Octavia’s shop with its broken window, but he’d been awake since four and he felt so heavy, and all these thoughts he’d spent so much time chaining together in the privacy of his own head smeared when he tried to speak them. He couldn’t hear his own voice over Jan’s resounding and silent disdain—even if he was pretty sure that disdain was just him filling in the blanks. Words bunched up. Sentences tangled. His voice ran thick as mud, then dried and hardened and with a lurch he found himself awake and blinking in predawn blue, a taste in his mouth fouler than Jan Chang’s tea, to find Octavia Zargoza knocking on the car window, waving, and offering a cup of fresh coffee.

The day blurred past. He hadn’t met with his first two students yesterday, so they wouldn’t notice that he was still wearing yesterday’s clothes, or that his hair was wacky. Oh, who was he kidding? They would notice, kids always did, but they wouldn’t say anything about it to him. After those meetings he had two hours until next period, which he’d ordinarily spend in a vain attempt to summit Mount Paperwork, but instead he sprinted to the 6, and home, and the kind of ten-minute shower-shave-dress-pack-an-overnight-bag routine he’d got the knack of back on the show. His apartment was efficient, spare, modernist, all things he told himself he liked, but in cold daylight it just looked empty. He found himself wanting a beheaded lion, or a trace of broken filigree. Back to the 6, then, and, in spite of construction and thanks to a breakneck run that undid most of the benefits of his shower and change of clothes, he reached his office just before the next bell.

“Look, Slade, Ms. LaJolla says you’re good at math.” What she’d written had more of a sense of could be about it than Robin was letting on, but he was here to nurture potential. And to spend six hours a day corresponding with colleges and program administrators. And to attend five hours of meetings a week. But nurturing potential was what he wanted to do. “Now, the school has plenty of resources to help with that. We have books of puzzles, and there’s this Intracity Math Olympiad which you might like—it’s competitive, but you’d also get to meet kids from all over the city who share your interest.”

No answer but marbles rolling over granite.

“I’m not trying to trick you, Slade. We don’t want you to be bored. School is all about potential, and growth, and discovery. Maybe you feel you don’t fit in, but there’s more to this place than you might think. Your teachers care about you, and so do your fellow students. We want to help you build a place for yourself. I want to help. What do you need?”

Slade looked up. The colors in those opals shifted, unreadable. “Bathroom?”

So Robin made it through that, and the meeting after, and the rest of the day until sunset, when he crossed the park again to join the stakeout. He was looking forward to it now. Everything had gone fine the night before, except for the sleeping part. Now, he had fortified himself with adrenaline and anticipation. He’d do better. After all, he knew something about how to be a hero.

The car was gone.

He looked all along the street and around the corner at a loss, until he tried looking up. The car wasn’t there, but Jan was, waving to him from the roof of the boxy building across the way with the flower shop on its first floor.

“What happened to the car?” he asked after he climbed the fire escape. God, he needed to find time for the gym. This sort of thing didn’t used to wind him.

Jan sat cross-legged against her duffle bag. Her tea thermos steamed. “Wasn’t mine.”

“What? I thought—I mean, you said—”

“Relax, Ruttiger. It belonged to a friend. She needed it tonight. Here.” She unzipped her bag without looking, pulled out a thermos, and handed it to him.

“It’s okay, I don’t—”

“It’s Assam. It’s sort of like Lipton if Lipton was good.”

He unscrewed the lid, sniffed, uncertain. Tried a sip. Blinked. “Oh, I like this.”

She rolled her eyes behind the sunglasses, he was certain, though he couldn’t see. But he sat down, and together they sipped tea as the streetlights came on and the sun set and the sky grayed out. There were so few stars, but the city’s constellations changed as offices and shops winked out and home lights on, people coming home, making dinner or ordering, finding their sofas and cats where they left them. Robin needed a cat. Or a rooster, or something. He yawned. Jan hadn’t. And she hadn’t slept at all last night.

“Did you sleep during the day?”

“I don’t sleep. Dreams are easy targets for mental manipulation. For the last two months I’ve trained myself on distributed napping: sleeping for fifteen minutes every two hours. I’m trying to adjust the ratio by only half-sleeping for thirty minutes every two hours.”

“Does that work?”

“Da Vinci used it to increase his productivity.”

“That’s not really an answer.”

“It works perfectly, right up until you die.”

That deserved a stronger answer than “Um.”

“I don’t consider that a drawback,” she said.

“Wait.”

“I mean, if you think about it, it’s true for everything.”

“No, I mean, wait.” He held out his hand, palm down, and leaned over the building’s edge. “Someone’s coming.”

Masks and tracksuits. Robin had believed the story, but there was always that spot of difference between hearing a report and seeing for yourself. Someone said, Don’t go through that door, there’s a giant snake in there, and the image your mind coughed up for “giant snake” was so vivid and particular that when you went through the door after all (you always did), you couldn’t see the real snake because it didn’t look like the one in your head.

The first masks peered around the corner, big-horned costume-shop noh-theater affairs, with hoods pulled tight to hide the heads that wore them, and black tracksuits with thin white stripes up the sides. The scouts motioned behind them, and other identical masks and tracksuits slipped around the corner up the sidewalk toward Zargoza’s. One held a bottle with a rag in its mouth. The yellow police tape across the shattered window looked very thin.

“We should call the cops,” Robin said. “911.”

Jan shook her head. “We have to assume the cops are reptoid-compromised. We can do this ourselves.”

“There are eight of them, and two of us.”

“We have powers,” she pointed out.

“They might have powers too. Or guns. You’re going to get us killed.”

“I’ve arranged for backup.” The tracksuits had gathered across the street from Zargoza’s. A Zippo lighter glinted in the streetlight. “Some things we just have to do ourselves.”

He was still trying to think of a way to tell her no, and was in fact reaching for his cell phone to call the cops, when he realized she wasn’t there anymore, and heard a clang from the fire escape and a loud cry: “Freeze, reptoids!”

Some did freeze. That happened more often than you saw on television. Even people who didn’t freeze might slip, or fall, or hurt themselves trying to turn and draw and fire and run all at once. Snap reactions came with instinct but mostly with training—so the number of tracksuits who didn’t freeze was worrying. A spark bloomed to flame on the rag in the bottle’s mouth, and as the tracksuit threw, Robin, who had better instincts than he was comfortable with, poured himself over the building’s edge.

Stretching yourself flat was harder than people without stretchy powers tended to assume. Like with super strength and heavy lifting, the mind played a role: what your body could do and what you knew how to ask it to do were two different categories, especially if you added the important adjective safely. People thought, if you were stretchy, you could just make yourself ribbon-thin, flat and broad as a rubber sheet. Well, yes, technically. Except, by the age of three or so, most human beings are used to the notion of having a rib cage. Even if the card you drew transformed your body into, for example, a highly elastic skinlike membrane around a hydraulic fluid—don’t ask about the nervous system, the answer to that question’s even more unsettling—thereby allowing you to splay and morph yourself so as to, say, spread yourself flat and broad as a tarp, with your arms hooked over lampposts, and use your body to shield your friend’s bakery from an incoming Molotov cocktail, doing so still caused a fair amount of mammal panic as what passed for your hindbrain insisted you were crushing yourself to death.

Robin wore exceptionally stretchy trousers and shirts in case of just such an emergency, but his sweater vest tore at the seams. The bottle bounced off his belly and shattered, leaving a burning puddle on the asphalt. He let go of the lampposts and snapped back down to normal size, stumbling as his limbs sorted themselves out. The rags of his sweater vest were smoldering; he rolled on the pavement, slapping at his chest. The tracksuits were watching him. He didn’t need to see past the masks to tell they were stunned.

So stunned, in fact, that they didn’t notice Jan Chang drop from the fire escape behind them. Her gloves were in her teeth, her hands bare. She caught one of the tracksuits by the wrist, and he dropped with a snap and a bright blue spark. She reached for a second but he pulled back and drew a knife. Sparks danced between Jan’s fingers, and her eyes glowed bright even behind her sunglasses. She raised her hands; the tracksuits drew back into a semicircle. One flicked out a collapsible baton. Two more drew knives.

Robin caught two lampposts and rubber-band-gunned off them, splattered against the wall of the building across the way, and tumbled down to resume his mostly normal form—a bit stretched—beside Jan. Her sparks glinted off the masks. The tracksuit she’d stunned found his feet, tried to raise his knife, and dropped it.

Tiny lightning bolts danced between Jan Chang’s teeth when she grinned. “Nice move. Got any more?”

He pulled a quarter from his pocket, cupped it in the webbing of his left thumb, pulled the webbing back three feet, then loosed. The quarter struck the nearest tracksuit’s knife hand with a sharp crack, and he swore and dropped the blade. The others backed up further, into the street. They weren’t scared—just timing for their rush. Waiting to see if he had any more quarters. Robin heard a rumble far away, like people in heavy boots running. Reinforcements? “This was a bad idea. We should have called the cops.”

“Relax, Ruttiger. I told you, we have backup.”

No. Those weren’t booted feet. He’d just never heard hooves on asphalt before.

He wasn’t any more ready than the tracksuits for the buffalo charge.

There was only one buffalo, but it was easily as tall as the tallest tracksuit, weighed as much as the whole group put together, and was doing forty miles an hour at a charge. The first tracksuit to see the buffalo might have preferred to describe his reaction as a warning cry, but it sounded like a scream to Robin. The tracksuits really were well-trained: without audible communication they realized how the odds had changed, and turned to run, weaving between cars, trying to keep out of horn range.

Jan whooped. “Way to go, Chowdown!”

“You know that buffalo?”

“Upstairs tenant. Come on! They’re getting away!”

So he ran.

The tracksuits couldn’t outpace a buffalo on a straightaway, but they ran out onto Bowery and into traffic. Horns blared and the buffalo’s hooves scraped on asphalt. Robin sprang from fire escape to rooftop to rooftop as Jan followed on the ground. Below, he saw the tracksuits split into three groups. “Stay on the north group!” he shouted, and Jan followed them across the road, waving apologies to the cars she ran between. Robin catapulted himself across the whistling gap and landed in a puddle beside Jan on the west side of Bowery. By the time he gathered himself, the tracksuits had vanished around the corner of Houston, but only just. Robin ran, and Jan ran beside him. He might be out of shape but the chase was burning in him now, and beneath that the joy of doing something right for a change. He skidded on the corner of Houston, glimpsed a sneaker and a tracksuit leg vanish around Mott, ran after, Jan thudding behind in her Doc Martens. He forgot to breathe—he didn’t really need to anymore, his skin took all the oxygen his system needed from the air—and his stride was smooth and easy. When he reached Mott he saw them turn east on Prince. Keep it up, keep it up, you’re almost there.

When he turned the corner, he stopped and began to curse.

A pile of tracksuits and masks lay on the corner of Prince and Mulberry. And Mulberry was wall-to-wall people: eating arepas, dancing to indie folk, lining up at the Korean barbeque burrito stand, drinking beer while doing all of the above. He’d walked through the street fair two days before. He hadn’t forgotten about it. He just hadn’t thought at all.

Jan skidded to a stop. “They must have changed shape. After reptoids shed their skin, they glisten in direct light for a few minutes after—we can still catch them.”

He sagged. “No. We can’t. We should have called the cops. They would have caught one of these guys. We should have done something, anything even remotely effective.”

“We saved the shop.”

“Great! Good. We were real heroes for two minutes! And what now? Do we wait for them tomorrow night, and the night after that? These guys aren’t amateurs. They could have killed us. Next time they’ll bring something to handle your buffalo buddy. This isn’t about reptoids, or mind control, or, what, wacky hijinks. Octavia’s real. We got into this to help her. And we just fucked it up.”

Jan took off her sunglasses. Without them her eyes were large and glowed softly. “You think I don’t know that?”

This was all wrong. That is, it wasn’t wrong, he wasn’t wrong, they should have called the cops, they should have done everything he said, but still somehow he’d just messed it up worse. Like always. He reached into his pocket for his phone. “I’m tired. I’m calling 911, and I’m going home to sleep. Some of us have work tomorrow.”

Thursday after school, Robin went to rehearsals. He still felt like he’d been crushed by a steamroller—he actually had been once, on the show—but he liked to see how the kids spent the time they could control. After a school day when he’d felt all eyes swivel toward him as he wandered through the hallway, only to swivel back to their own business when he turned, after even Ms. LaJolla pursed her lips across the lunch room table in what he felt certain was judgment, he needed to sit in a dark room and watch someone else take the spotlight.

He clapped. He couldn’t stop himself. The kids were good. When he’d been in high school theater, he’d been so impressed by how his friends transformed from the dressing room to the stage, melted by the lights into their roles. Now it seemed staggeringly obvious the girl playing John Wilkes Booth was just fifteen, her mustache pasted on. There was something pure about that, though femme Booth would probably have been mortified to hear him say so: the clarity of performance, the person revealed underneath.

After the rehearsal, he congratulated the director—Mr. Cho—and the kids, and ended up in the empty theater with a Broadway actress named Baker (“Like Tom, or Josephine,” she’d said with a half smile in a British accent he couldn’t place, “but Abigail”) who’d come in as a vocal coach, on what he’d heard whispered was a sort of . “The kids love you,” he’d told her after Mr. Cho introduced them, and it was true. Part of that was the Broadway mystique, and maybe the slight lawbreaking edge, but she was glamorous and handsome and tall and had hair like she should have been in Cabaret, with tattoos on both arms. Booth had blushed and gone corpse-still every time Baker so much as glanced in her direction.

“They’re perfect,” she said. “I mean, they’re fabulous. Working with young talent like this, with no agents or managers, is sort of the dream, isn’t it? Pure theater. And I say that from the point of view of someone who’s in the wrong line of work. Dealing with them every day, though, probably like ice cream for breakfast all the time, if you’re lactose intolerant. Slightly. Sorry, metaphor needs work. Anyway. Assassins in a high school—bit of an odd choice?”

“I don’t know. Less so here than most places.”

“I suppose.” She stretched her arms over her head, and they kept stretching until they reached the ceiling, then snapped back. “Ow!” She rubbed her shoulders.

“I hate it when that happens to me,” Robin said. “Once I threw my jaw out yawning. How long have you been stretchy?”

“Just since a few minutes ago,” she said. “That’s me, you know, Abigail Baker, the Understudy.” When she sketched a bow, her arm swooped elongated behind her. “Your talents are my speciality.” When she looked up, her eyes widened in an expression Robin dreaded. “Just a mo. Stretchy. I remember you. Ruttiger—Mr. Rubberband, right?”

“Just Rubberband. And I don’t go by that anymore. Just Robin, these days.”

She really was a good actor, Robin thought. Her expressions were transparent: he could read her trying to stop herself from speaking, then deciding she’d rather not pass the chance. “I watched American Hero religiously. I watched a lot of TV between auditions. When you retired from public life I was so bloody furious. At you, I mean. Yes, we have just met, and it is terribly unfair of me to say, and, obvs, you have no idea who I am, but, new policy, honesty at all times. Back then, here were my thought processes: I’m trying to break in; no luck whatsoever; big debut, gloriously romantic, also an enormous storm of bollocks—and here was this guy who lucked out, got the golden ticket. Only rather than appreciate it, off he goes. Oh thank you so bloody much. I mean, have you seen the world? We don’t really have love, do we? Instead we have celebrities. Those were my thoughts at the time. However. Adulthood. One sees mistakes were made. I was a child. I was being unfair. Now, I really get it. You were right. So, well done there. And thank you for remaining still for all that.” She set her hand on his arm, and his experience of British people was too limited to know whether that felt as forward for her as it did for him—they did the cheek kissing thing over there after all, didn’t they, or was that France? “It’s good to see you happy. To see anyone happy. Well, that is my portion of Too Much Information today, and now I shall retreat—”

“No,” he said, “it’s all right. Thank you.” And he meant it, more or less.

Was he happy? He walked the halls to his office, unsure.

His hand was on his office door and his mind on home, sleep, solitude, when a voice like crushed granite interrupted the quiet of his skull. “Mr. Ruttiger? Me and the guys were talking and, um. There’s something you got to see.”

“Look, Mr. R, you gotta understand, my jokers and me, we’re not into anything bad, right? We just keep an eye out. Take care of each other. But soon as you start to, like, you hang around, and you get so’s you know each other, and you make up a handshake, a special kind of nod, not meaning anything by it, people get ideas. We’re not doing wrong, right? Like okay maybe once in a while there’s some jokers want to get scrapping on your block, so you scrap back, and sometimes nats come down to start shit with little jokers who can’t defend themselves. Squishy people. I don’t mean you, you’re okay, Mr. R, you got your own back, I’m talking about, like, Smalls, who’s small, or Gabby who don’t have a mouth so she can’t call for help. God made me a rock so I got to be a foundation, you figure?”

“I figure.” There were parts of Jokertown not even realtors went, buildings that had been rat traps and fire hazards long before the virus, and after that turned weird, shellacked by three generations of joker inhabitants, crumbling masonry glistening with slime, veined by crystal, studded with papery nests for wasps the size of toddlers.

By itself, those hazards wouldn’t have kept the street safe. New York realtors had bulldozed and built over worse, and lied about it on the environmental impact statement. But the locals were fiercely loyal, and no one yet had worked up the entrepreneurial gumption to offer enough money to break that bond for an apartment wallpapered with its previous owner’s cast-off skin. Robin had walked most of Jokertown on one lunch break or another, but never this four-block stretch. They didn’t have places like this in Ohio.

“But you start that and then the police gall you, right, like every group of jokers is a gang or some mafan shit like that. But we heard you and Miss Jan scrapped them tracksuit guys who came for Octavia’s last night.”

“You heard about that?”

“Shit yeah, everybody heard! Why you think all and them was watching you all day? Some badass shit man! Wha!” Slade mimed a channel 5 kung fu movie pose, and an uppercut. The ground shook when he bounced on his feet, and rock flour drifted from his joints. “Yeah. So I added it up and thought maybe you’d like to know your tracksuit boys hang out here.” He nodded across the street and down: a building with broken windows boarded up, a weathered illegible sign bearing a picture that might have once been of a car. “They moved in six weeks back. Real serious tough guy shit. We spied ’em, didn’t want people bringing poison onto our street, that’s how jokers get hurt, you figure?”

“Yes.” It was an ideal hideout: near their target, and cop-free.

“But they kept quiet. Scoped up by the school—but nobody starts mafan by the school, that’s how jokers get sent up federal. We figured it for okay. But they can’t be hurting on Miss Octavia. I’d go to the police, the Fort Freak crew’s okay, but maybe I go to them and they ask me, Slade, why you coming to us with this now, right? What else you got? And maybe Big X or one of hers sees me going into Fort Freak and asks, Slade, why you in with police now? But you, Mr. R, you’re okay.”

“Would you be willing to talk to the cops? If I made the introduction?”

“I don’t know, Mr. R. For Miss Octavia, maybe.”

But it wouldn’t be enough. Arresting the tracksuits might slow Mikhail’s plan—if it was in fact his plan—but if they wanted Octavia’s place safe, they needed more. They needed to tie the man to the trouble. “Have you seen a guy in a suit with them? A big guy, with an Eastern European accent?” Slade looked confused. “Like Dracula?”

“Mr. R, man, they all talk Dracula. And nats all look the same. Me and my jokers, we gotta go to school or else they send for us, so if they do things during the day, we wouldn’t see nothing.”

Shit. Okay. Think, Ruttiger. We’ve got a street cops don’t patrol, close-knit community, outsiders will be noticed, but good luck getting anyone to testify. You need documentary evidence. But this was the kind of place where city cameras would keep getting mysteriously eaten. Think harder. Take in your surroundings. There’s the building covered in the thin layer of ooze, there’s the apartment walled in crystal, there’s the wasp’s nest making an uneasy humming noise, and there’s—

“Slade?”

“Yeah?”

“What’s with that apartment there? With three sets of bars over the windows, and aluminum foil?”

“Mr. R, you don’t want to be bothering her. That’s Mama Salva, she’s straight up paranoid, man. She thinks everyone’s out to get her. You talk to her, and it’s all, the government, and the aliens, and like the Kings of France and shit. My mama says she’s thought there was people out to kill her for at least twenty years. She paid some of my jokers to paint the hexes on, and they said she got the place all wired up, mics and cameras and junk.”

“Any of them pointed at the street?”

Slade’s eyelids ground down over his eyes, then up again. “You can’t be going in there, Mr. R. Mama Salva don’t talk to nobody. She’s going to hex you.”

“No,” he said. “You’re right. She won’t talk to me. But I think I know someone who speaks her language.”

He didn’t need to jump the fence to reach the stairs down to Jan’s apartment—Jan, it seemed, just lacked patience for the gate. The basement door was unlocked, and the lights weren’t on, so he fished out his phone and soft-shoed through the cluttered dark tool room with its dripping pipes to a shut door beside a washer-dryer, half-hidden behind paint cans, wishing the whole time that he hadn’t been such an unreconstructed dink the night before. The door handle turned, but the door stuck. He leaned into it, pressed harder, shoved. The door gave. He tumbled through into blinding light, and landed on a bear.

The bear wasn’t alive, but a bearskin draped over a chair oozing foam out the remnants of its upholstery. The fake fur smelled like dust, but the room was full of sage and incense and weed smoke—not to mention, as he forced himself back to his feet, bulletin boards, twenty of them, on the walls, in freestanding easels, festooned with news clippings and website printouts. The room was a spider’s mess, multicolored yarn lines sagging from pushpin to pushpin across the space between corkboards, and in the heart of that web stood Jan Chang, wielding a broken pool cue as a pointer. A man sat on the couch: squat and broad, the kind of big that didn’t need to suggest muscle beneath the flesh and the ripped jeans and the gold chain and the stained tank top—the muscle was as broadly stated as the rest of him. The big man’s eyes got narrow, and he rumbled up, dislodging a red piece of yarn that linked Queen Margaret to Prince Charles, which was silly, because there wasn’t a Prince Charles unless the royals had shuffled while he lost track. “Hey, buddy. This is a private residence here.”

“Ruttiger! No, Fred, this is Robin Ruttiger. Remember? The guy from last night.”

“That guy?” Fred didn’t seem encouraged by the association; Robin didn’t blame him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, hands up. “Jan, I was a jerk last night. But I need your help.”

“It’s cool, Robin, you were right. I wasn’t thinking about the bigger picture. I sat down to thinking, and that’s where all this came from.” She waved her hands to include the corkboards. “Fred, remember, Robin saved Octavia’s shop, he saved me—he’s okay.”

“It all gets a bit fuzzy,” Fred mumbled. “You know, the horns and all make it hard to concentrate. Buffalo brains are tiny.”

Robin blinked. “You were the buffalo?”

Jan frowned at the distraction. “Right, sure. Ruttiger, meet Fred Minz. Fred can turn into animals he eats. Fred, meet Robin. Stretchy guy. Rubberband, Chowdown. Chowdown, Rubberband. Can we get on with this, or do we have to have a crossover special?” No one answered. “Good. Now, as I was saying, after some substantial digging I’ve assembled two competing theories. The first has to do with reptoid manipulation of the Rosicrucian sect and internal Freemason magipolitics which affected the pre-grid street layout of southern Manhattan, interfacing with secret Majestic 12 experiments conducted here through the ’70s and ’80s when Jokertown was an undisclosed federal testing ground for psychoactive weaponry. The other has to do with the fact that our good friend Mikhail Alexandrovitch is a mid-level operator for Ivan Grekor of the Brighton Beach mob. That explains why the goons were so well-trained: the Russian mob has access to a lot of ex-Spetsnaz guys. Good thing Spetsnaz are notoriously weak against buffalo.” Frank chuckled. “Anyway. Alexandrovitch a semi-legit errand boy, emphasis on semi, and real estate development is a great vehicle for money laundering. Our man’s assembled a collective of investors currently operating under the name of the Twenty-First Century Retail Group, who’ve committed a large amount of capital to build a high-rise luxury condominium complex in Jokertown, provided Mikhail acquires the free and clear rights to demolish Octavia’s building. The other owners in the building all accepted down payments over the last year from puppet organizations I’ve traced back to Alexandrovitch—he’s not as good at covering his tracks as he thinks—because they assumed Octavia would never sell. They were right. But now the Twenty-First Century Group’s run out of patience, and Mikhail’s taken matters into his own hands. They’re both compelling theories; I’m not sure how to choose.”

Robin boggled as his brain raced to catch up with Jan’s mouth. “How did you put all that together?”

“I was a financial analyst before my card turned and I had more important things to worry about. But even with the paper trail, we don’t have anything to tie Mikhail to the attacks.”

“That,” Robin said, “is where I think I can help.”

“Back up,” Jan said when they stood in front of the door, with its six locks and chains, its pasted prayers, and the poorly disguised reinforced plates to either side that would have stopped a prospective burglar from just sawing through the wall.

Robin retreated a step.

“I meant, around the corner. The fewer people she sees through that peephole, the better. Plus, all due respect, I look more like a joker.” He didn’t think his expression was that skeptical, but her frown suggested otherwise. “Come on. I can take care of myself.”

When he was safely down a flight of stairs, Jan knocked. The locks were heavy, slow and vicious to unlatch. Some of those high-pitched whines you never realized you were hearing until they stopped, stopped. The door opened on at least two heavy chains.

The woman’s voice was sharp and cold. “Who are you? Who sent you? What’s the secret?”

“We don’t have time for the usual protocols.” Jan was talking fast. “I’m with the resistance. We’re being monitored. I need critical information from a secure facility. I was told you’re the person in this district I could trust.”

“Told by who? What’s the secret?”

“You of all people should understand that I can’t divulge my contact’s identity.”

A considering silence. “What’s the secret?”

He held his breath.

“Blood and gold,” Jan said. “Isn’t it always?”

The door slammed. Chains clanked. The door opened again. “Come inside. This hallway’s only Lavender secure.”

Footsteps, and the door slammed shut, and locks engaged.

Robin sat on the steps and waited. He pressed his thumbs together. A stooped gray woman lurched up the stairs under a layer of groceries; he helped her with them. Two kids came home from school and let themselves into their apartment. On the first floor, someone started practicing trombone.

Robin was playing jacks with the kids when the locks disengaged again, and the door opened. He’d been playing by snapping his hands out to catch the jacks (the kids cried not fair, but one of the little hypocrites was telekinetic and the other had gecko palms), so he turned his head all the way round on his neck to face Jan when she emerged. The boy laughed, “Eww, gross!”

Jan put her glasses on with one hand. “I’ll never understand the Merovingians. So much time worrying about the blood of Christ, when obviously organized religion is a Gray plot to prepare us for invasion.”

“Were there cameras? Did you get the footage?”

She grinned and held up a gleaming disc.

The next morning, when Mikhail came for Octavia, they were waiting.

Octavia had covered the shop’s window with a tarp that didn’t keep out the dawn chill. Robin hunched deep in his coat, over his coffee. He didn’t look at Jan, seated against the other wall, scrawling red sharpie circles and arrows on the morning’s Times. A one-eared tabby cat sprawled on Octavia’s counter, very interested in his own dreams.

“Good morning, Ms. Zargoza!” Robin heard Mikhail’s shark-toothed grin even though his back was to the man. “Is shame about the window. Dangerous neighborhood, I hear.”

“Mikhail. It’s never been dangerous for me before.”

“But nothing changes, no? Is New York! Have you taken chance to consider my offer?”

“I’ve been considering it for two months, Mikhail. And after two months, the answer’s still no.”

“Is a big mistake, Ms. Zargoza! I understand, is sentimental, I feel this way myself, I have been reluctant to part with old things because they belonged to my grandfather in this war or that. But we must move on, or else the world moves on around us. Especially in such dangerous places. A window today, who knows tomorrow?”

“Is that a threat, Mikhail?”

He faked shock, hands raised. Robin watched him in one of the mirrors Octavia hung to make the cramped shop feel bigger. “Is no threat. I hear same stories as everyone. Tracksuit men come to break windows, start fire. Jokertown is dangerous place, yes? And every day more dangerous.”

“That’s funny, Mikhail.” The very tall man in the very long coat who ducked through the bakery’s front door wasn’t wearing a badge, but even without the two-cop escort his bearing screamed police. “We have surveillance footage that shows you meeting with the men who tried to torch Ms. Zargoza’s shop. Tracksuits and masks and everything. We paid them a visit, and one of them remembered where he put his tongue.”

“Detective McTate.” Mikhail’s eyes narrowed, and he got very smiley and loose. “You have some honest mistake, I am sure.”

“Not this time, Mikhail.” The rolled newspaper the tall man held compressed and sharpened into a paper blade. “Let’s do this the easy way.”

Mikhail’s eyes flicked from McTate to his escort. The smile’s corners turned down, and the gleam in his eyes sharpened into hate. Then he moved, fast—not for McTate, but for Octavia.

He didn’t make it. Robin slung out one arm and snared his fist before it could connect. Then Jan zapped him. Then the tabby cat tackled him, only it wasn’t a cat anymore, but a heavyset ginger cop, still missing an ear, but in ample possession of a fist.

Police stuff followed after that. The three of them kept it together all the way through. Octavia only collapsed when the cops and Mikhail were gone. Jan hugged her, then glared at Robin until he, cautiously, stepped forward and joined the embrace.

“I can’t believe it’s over,” she said when the tears were done. “I’ll have to fix the window. I don’t know where I’ll find the money for that. But people will keep coming. I’ll make it work.”

“I’ll pay,” Robin said before it occurred to him to stop himself, and then there were more hugs, and violent thanks, and he couldn’t take it back.

It was after the hugs and the tears and the free coffee, and back out on the sidewalk, that he confessed to Jan Chang, “I don’t know how I’m going to afford that window. I’m using my savings to cover my rent as it is.”

“Move,” she said.

“Where?”

“The apartment upstairs from my place is reasonable. And Chowdown needs a roommate.”

“Think you could put in a word with the landlord?”

She laughed and punched him in the arm. It tingled. “Ruttiger, I am the landlord.”

He took the coffee to his office. There were eyes, yes, but he realized now they weren’t staring at him—watching only, with interest and approval. A gaggle of seventh graders trading Pokémon cards in the hallway stared open-mouthed as he walked past. He marched into his office, set the coffee down on his desk, and sat firmly on his chair—sure at last in his place, until the chair collapsed beneath him.

His head hit the floor. His feet hit the desk.

And, in a slow shuffling avalanche, Mount Paperwork collapsed onto his face.

He began to laugh. It had been a long time since he laughed. His sides hurt. He gasped in a dusty papery breath that filled his whole body from his ankles to his fingertips. The paperwork rustled and crumpled around him like a nest.

“Um, Mr. R?”

He slung a long arm over his desk and pulled himself to his feet. “What’s up, Slade?”

“I wanted to talk with you. You know. About.” Slade looked both ways as if afraid he’d been followed to the office, and mouthed: “Math.”

Text copyright © 2018 by Max Gladstone

Art copyright © 2018 by John Picacio

Buy the Book

Fitting In