Where to even begin? I loved this book. If you’ve ever loved any genre of music you should read it, and if you love horror you should read it, and if you’re obsessed with the plight of the American working-class you should really, really read it.

Grady Hendrix’s latest extravaganza of horror is wild and fun, genuinely terrifying in places, and also somehow heartfelt. It’s like The Stand and Our Band Could Be Your Life had the best baby (Our Stand Could Be Your Life?) and somebody slapped a Viking helmet on it and taught it to shred a guitar.

I should probably state at the outset that I am not a metalhead. I appreciate metal. I love Lord of the Rings and I like D&D and I’m a fan of Norse mythology, and as a person who tried to play guitar for about five minutes, I stand in awe of people who can make their hands move up and down a fret that fast. Having said that, it just isn’t my scene. I like grunge, glam, and goth. Give me Joy Division! Give me Marquee Moon! Give me Sleater-Kinney’s first album! But I also feel a very strong affinity for the metalhead. Kids in leather jackets and denim jackets, patches all over, shredded jeans, potential band logos drawn on every notebook and textbook, sitting in cars and basements where they can turn their music up enough to feel it. Most of all, I feel the protective impulse I have for any group of kids who gather together to celebrate their particular nerdery, only to have asshole adults and bullies sneer at them and threaten them. (Satanic Panic was very real, and it fucked up a lot of lives.) So even if I’m not into their music, personally, I consider myself metal-friendly. A met-ally, if you will.

Hendrix digs into the subgenre and along the way gives us bits of knowledge about a lot of different types of metal. Kris is into Sabbath, initially, and understands that under all those white British boys there was a river of Blues, but over the course of the book we meet drummers who are into the mathematical constructs under the music, people who love Slayer, people who love Tool, people who refuse to admit they used to like Crüe, people who are into heavy Viking metal, like Bathory and Amon Amarth, and people who prefer the radio-friendly nu-metal of Korn and Slipknot.

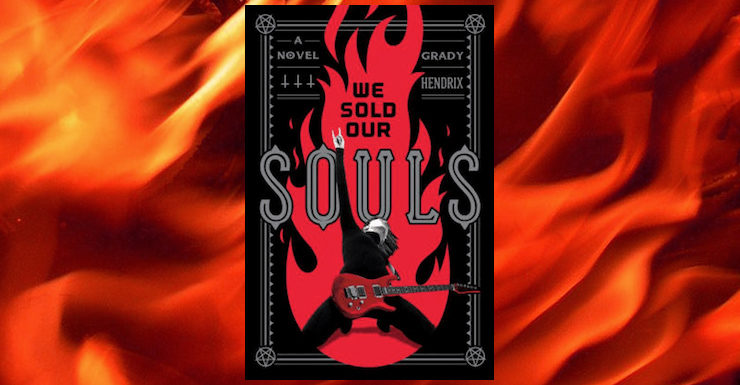

We Sold Our Souls is an inversion of the typical rock story. We meet Kris Pulaski as teenager just picking up a guitar and picking out her first chords. Then we skip ahead to see her at the other end of her career, burned out, broke, post-lawsuit and rock’n’roll excess, living in a borrowed house and working at a Best Western. When her former bandmate/best friend/nemesis Terry Hunt goes out on a farewell tour, she decides it’s time to get their old band back together, confront Terry, and finally learn why he betrayed her all those years ago. Her journey takes her all the way to the biggest music festival in history, looping across half of Pennsylvania and Northern Kentucky and all the way to Vegas, as she gathers her ex-Dürt Würk bandmates—guitarist Scottie Rocket, bassist Tuck, and drummer Bill—and tries to convince each of them that something weird and unnatural happened on the night Terry quit. She meets with resistance both human and supernatural on her quest.

Through this framework, Hendrix looks at the aftermath of a rock career. Kris was pretty successful—until she wasn’t—and Hendrix shows us all the compromises people made for that success. He gives us a very interesting portrait of a modern artist, and interrogates the ways our current society makes it impossible to create art. And then, in a great, horrific way, he peels back the curtain and finds that sinister forces might be working against those artists.

This is, make no mistake, a horror novel. There is a chapter that was so intense I had to put the book down for a while. There is supernatural shit afoot, and Hendrix’s descriptions are so evocative some of it showed up in my nightmares. There is a lot of violence and gore, and those of you who remember the haunted IKEA-esque furniture of Horrorstör will not be disappointed. But having said that, none of it felt gratuitous—Hendrix sets his stakes extremely high, and then the consequences have to be dealt with.

In fact, stakes, consequences, and responsibilities are a huge amount of the subtext here. Not just real world consequences like a shitty apartment or a pile of debt, but Hendrix digs into the idea that all of our tiny little mindless decisions are essentially a choice to sell out—and I don’t want to spoil stuff by saying what we’re selling out to—but it becomes a running theme in the book that corporate, soul-sucking life is literally sucking the soul out of life:

Now people sell their souls for nothing. They do it for a new iPhone or to have one night with their hot next-door neighbor. There is no fanfare, no parchment signed at midnight. Sometimes it’s just the language you click in an end-user license agreement. Most people don’t even notice, and even if they did, they wouldn’t care. They only want things… [H]ave you noticed how soulless this world has become? How empty and prefabricated? Soulless lives are hollow. We fill the earth with soulless cities, pollute ourselves with soulless albums.

Also as in Horrorstör, class issues are woven into the book from beginning to end. Kris is the middle child and only daughter in a working-class Eastern Pennsylvania family. When she’s a kid in the early ‘90s, her parents are able to have a house, cars, and three kids, two of whom go to college. One of them vaults himself up to the middle class and becomes a lawyer, while the other one goes into the military and becomes a cop. Her parents can afford to give Kris guitar lessons when she asks. We get the sense that things are tight but workable. But by the time we check back in with her in the present day, Kris’ childhood home is in a nearly-abandoned neighborhood, surrounded by houses that are falling down, and the few neighbors she has left have been shattered by opioid use and economic freefall. Kris works full time at the Best Western, but is still driving her Dad’s 20-year-old car, and the idea of having to leave that childhood home and move into an apartment is debilitating—how the hell is she going to scrape together a deposit?

Back here, abandoned houses vomited green vines all over themselves. Yards gnawed away at the sidewalks. Raccoons slept in collapsed basements and generations of possums bred in unoccupied master bedrooms. Closer to Bovino, Hispanic families were moving into the old two-story row homes and hanging Puerto Rican flags in their windows, but farther in they called it the Saint Street Swamp because if you were in this deep, you were never getting out. The only people living on St. Nestor and St. Kirill were either too old to move, or Kris.

Buy the Book

We Sold Our Souls

This continues throughout the book, as we meet character after character who is just barely getting by in America—and I soon noticed that the only ones who had nice middle-class homes and two cars in the driveway were the ones who’d made various deals with various devils. Melanie, a metal fan whose animation degree is gathering dust, works double shifts at a place called Pappy’s, where she’s as likely to get slapped on the ass by frat boys as she is to get a decent tip. Her world is McDonalds and Starbucks and Sheetz gas stations, and a boyfriend who complains endlessly that the Boomers ruined his future, but whose biggest plans only extend as far as the next marathon gaming session. Melanie and Kris form a counterpoint throughout the book, Melanie as an audience member, and Kris as the one on stage, to tell us a story that hovers at the edge of the book: the story of women in rock. Kris refuses to let her gender define her: she wears jeans and a leather jacket, and says repeatedly “A girl with a guitar never has to apologize for anything.” Her guitar becomes her weapon, her magic wand, the phallic key that forces the boys to shut up and pay attention—but the implication is that while she only feels at home onstage, she’s also only safe onstage. Melanie, meanwhile, shows us the other side of this equation. She lives her life as a girl in genre that seen as male and aggro, and as another pretty face in the crowd she has no defense at all from the men who take crowdsurfing as an invitation to grope.

The importance and power of music is celebrated under everything else. Under the horror and the working-class realism, the touchstone is that all the real characters in this novel, all the people you genuinely care about? Music is their heartbeat. It gets them through terrible shifts and through the deaths of their parents. It takes them onstage. It gives them hope and meaning. It’s easy to get snarky about metal, and Hendrix is a hilarious writer, but he always always takes the music seriously. Just as Horrostör was a book about work that was also a book about a nightmarish big box store, and just as My Best Friend’s Exorcism was a book about demonic possession that was also about the power of female friendship, this book is about music and found family just as much as its about an eldritch horror lurking beneath the facade of modern American life. And it rocks.

We Sold Our Souls is available from Quirk Books.

Read an excerpt from the novel here.

Photograph by Marcus Obal.

For all that she’s not a metalhead, Tool is one of Leah Schnelbach‘s favorite live acts. Come throw the horns up with her on Twitter!