I recently decided to reread T.H. White’s legendary classic, The Once and Future King. At first, I was delighted by the exact book I remembered from my youth: Wart (young King Arthur) being taught by Merlin, goofy King Pellinore, sullen Kay, a lot of ridiculous adventures, with some anti-war, anti-totalitarian commentary mixed in for good measure.

As I continued, I found some bits I didn’t remember. I hadn’t noticed the occasional asides about the “base Indians.” White says archery was a serious business once, before it was turned over to “Indians and boys.” He talks about the “destructive Indians” who chased the settlers across the plains. I did not feel good about this.

Then I found the n-word. Granted, it was used by a bird—and an unhinged one at that—in a rant where the hawk blames the administration, the politicians, the Bolsheviks, and so on for the state of the world. Another character rebukes him for his comments, though not for using the word specifically. Later in the book, Lancelot uses the same word to describe the Saracen knight, Palomides.

I couldn’t believe it. Not so much that the word was used, but the fact that I didn’t remember it. I was equally shocked that I didn’t remember the denigrating comments about Native Americans. It left me feeling distressed about the book…I had been trying to convince my teenaged daughters to read it. Had that been a mistake?

Most of us who love speculative fiction run into this problem at some point. There are classics of the genre that are uncomfortable for various reasons. Some of them are straight-out racist, or unrepentantly misogynistic, or homophobic, or all of the above. How and why and when we come to these realizations can change depending on who we are, as well: I’m guessing none of my African American friends have come across the n-word in a novel and “not noticed,” even as kids. The fact that I hadn’t noticed or remembered the use of that word, even as a child, is a sign of my own privilege. And for all of us, regardless of ethnicity, gender, age, class, orientation, or other factors, there will be moments and experiences of growth and change throughout our lives—but the books we loved have stayed the same.

We can have a debate in the comments about whether Tolkien’s world is racist, but in general, if someone in Middle-earth has black skin (the Uruk-hai, at least some other orcs, the Southrons) or are described as “swarthy” (the Easterlings, the Dunlendings), then you better believe they’re going to be bad guys, with very few exceptions. Sure, there are plenty of white, non-swarthy bad guys, too, but it’s hard to escape the sense that it’s the people of color you need to keep an eye on, in these books. (Yes, I know Samwise sees a dead enemy soldier in The Two Towers and reflects on whether he might have been a good person who was lied to. This shows, I think, Tolkien’s empathy for people and desire to humanize and complicate the Haradrim and other dark-complexioned combatants, but this is one brief paragraph in a massive trilogy. It is the exception and not the rule.) C.S. Lewis’s Calormenes are similar in this respect, though at least we get Aravis and Emeth, who are good-hearted Calormenes. We had best not even get started on the work of H.P. Lovecraft, though.

So what do we do? How can we deal with beloved or transformative books, many of them true classics, that also happen to be prejudiced, or racist, or sexist, or homophobic, or (insert other horrible things here)?

Here are four questions I’ve been using to process this myself.

1. Is this a work I can continue to recommend to others?

Can I, in good conscience, tell a friend, “This book is great, you should read it”? Or does the book possibly require some caveats?

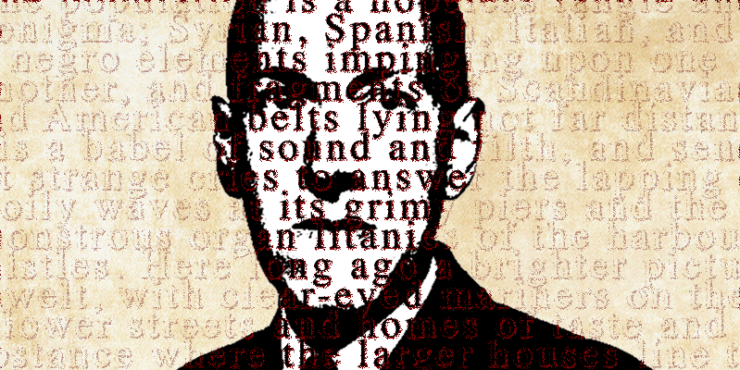

Me, personally, I can’t recommend H.P. Lovecraft. For instance, in “The Horror at Red Hook” he writes that Aryan civilization is the only thing standing in the way of “primitive half-ape savagery.” Lovecraft’s wife, a Jewish woman named Sonia Greene, constantly tried to dissuade him of his racist views while they were married, apparently without success. He wasn’t just a “product of his time”—he had some extra, virulent racism of his own all stored up.

But T.H. White…well, I feel torn. I could warn my kids about his views of Native peoples. I could discuss the issue with them, make sure they know that it’s not okay to use the n-word, ever. That could be a possibility: to recommend, but with some major caveats.

When I think about it more, though, I imagine recommending the book to one of my African American friends. What would I say, “Hey, this is a really great book about King Arthur but it says the n-word a couple times for no good reason; I think you’ll really like it…”?

And if I can’t recommend it to my African American friends, or my Native American friends, then how and why am I recommending it to others? So I’ve come to the conclusion that no, I’m not going to suggest The Once and Future King to others.

This is the first question I have to wrestle with and come to a conclusion when it comes to any problematic work. If I say “yes, I can recommend this” and am settled, then fine. If it’s a “no,” then I go on to question two.

2. Is this a work I can continue to enjoy privately?

I already mentioned that I don’t read Lovecraft because of his racist views, which are central to the narrative. Others are able to set those elements aside and enjoy the cosmic horror on its own merits.

With folks like White, Tolkien, and Lewis, we see people who are steeped in colonialism and racist assumptions. Thus the defense that gets trotted out whenever these problems are discussed: “They were a product of their time.” This is one of the challenges for all of us as we delve further into the past reading the classics—of course there are assumptions and cultural practices and beliefs that are at odds with our own. Where is the tipping point of not being able to look past these differences, the point where we can no longer enjoy reading these works?

Look at Roald Dahl. A writer of delightful children’s stories, Dahl was also a self-avowed anti-Semite, who said that there was something about Jewish character that “provoked animosity.” He went on to say, “even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on [the Jews] for no reason.” Anyone who categorizes Hitler as “a stinker” and reduces genocide to getting picked on has a very different value set than I do.

And yeah, there’s trouble in the text, too, like the little black Pygmies (later Oompa-Loompas) who gladly enslave themselves in exchange for chocolate in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (their portrayal was rewritten significantly in later editions of the novel), or the charming line from James and the Giant Peach, “I’d rather be fried alive and eaten by a Mexican.” Some of these things are changed in later, updated texts. So the question becomes, Am I able to set aside what I know about the author and the racism inherent in the text and still enjoy the book?

I didn’t finish my re-read of The Once and Future King. It was disappointing for me, because I loved the book a lot as a kid. But a lot has changed since then; I’ve changed since then. I also didn’t have any Native American friends, or many African American friends back then, and I have a lot of both now. I didn’t even notice the n-word or those dehumanizing comments about First Nations people when I was a kid. But now I do, and that has altered the book for me. Nostalgia doesn’t counteract the racism of the text. I like and respect my friends better than I like the book, and I don’t feel comfortable reading a book that’s taking aim at my friends. It has lost its magic.

Sometimes, like poor Susan Pevensie in Narnia, we outgrow worlds that were once meaningful to us. That’s okay. Leave the book on your shelf for sentimental reasons if you want, but don’t feel bad about leaving it behind.

There may be a period of mourning for these abandoned books. Or maybe, in some cases, you decide it’s a book you wouldn’t recommend to new readers, but you’re able to enjoy revisiting it yourself. Whatever our answer to question two, though, question three can be of help!

3. Is there another work that doesn’t have these problems, but occupies the same space?

In other words, if I can’t read White’s book and enjoy it anymore, is there another retelling of Arthurian legend that might take its place? Or in place of another kind of problematic work, is there a fantasy world I could explore that isn’t full of sexual violence? Are there speculative novels that present a different picture of human society when it comes to women or people of color or sexual orientation or whatever it may be?

For instance, Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country both critiques and replaces Lovecraft for me; it engages with the original work and its problems while also delivering a satisfying cosmic horror narrative. While I personally can never suggest reading Lovecraft, I heartily endorse Lovecraft Country. If you’re disturbed by White’s descriptions of Native Americans, there are more than a few wonderful Native speculative writers publishing fiction right now, and if you haven’t read Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning then you are in for a treat.

There are so many amazing writers producing incredible work, and even more new voices springing up every day, that we shouldn’t ever have to compromise in search of stories that aren’t built on hateful, troubling, and outdated attitudes. I would love to hear some of your suggestions in the comments.

The next question is a sort of extension of the third, but given how many of us fans in the speculative fiction community are also writers or artists or cosplayers or singers or podcasters (et cetera), I think it’s worth asking…

4. Can I create a work that is a corrective to the problematic work I love?

Much of new and current literature is in conversation with the literature of our past. Can I make a work of art that captures what I love about my favorite stories, but also recognizes and critiques the failures of those works?

Listen, I still love J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis despite their dated and simplistic treatment of race. I really do. The race issue continues to nag at me, though.

So I set out to write a book that works through my feelings on this. I started with a teenaged woman (Middle-earth has fewer women in the center of the narrative than I would like, as well) named Madeline. She’s privileged in a lot of ways: white, upper class, well educated, smart, and likeable. The only catch is that she has a terminal lung disease.

In the book, a mysterious elf-like guy named Hanali shows up and offers her a deal: come to the Sunlit Lands for a year and fight the evil orc-like bad guys for a year, and she will be completely healed. So Madeline and her friend Jason set off to help the beautiful “elves” fight the swarthy “orcs.” They haven’t been there long when they realize things are not so simple as they were led to believe… it appears they may be fighting on the wrong side. Madeline has to make a choice: do the right thing and lose her ability to breathe, or ignore societal injustice for her own benefit.

The book, The Crescent Stone, is so deeply shaped by my childhood heroes. It’s a portal fantasy, and an epic, but it’s also a conversation about how the epic genre—by nature of being war propaganda—is set up to vilify the enemy and unquestioningly glorify our own soldiers. The epic as a genre did not begin as a nuanced conversation about the complexities of human interaction in war or crisis, but a way of reminding the listeners and readers that there are only two categories: the heroes (us), and the villains (them).

And of course, many other authors have used their fiction to interrogate and offer a corrective to the aspects of their chosen genre that should be questioned and addressed, and this has been a tradition of fantastic literature from early on. Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea novels pushed back against the conception of the fantasy novel as violent quest, and also featured a dark-skinned protagonist in the first book, and a middle-aged woman as the central character of the fourth novel. Saladin Ahmed and N.K. Jemisin (among others) have pushed back against the idea that fantasy settings have to be Eurocentric just because that’s the traditional default. I’m currently reading The Bannerless Saga by Carrie Vaughn, which critiques and subverts the familiar post-apocalyptic narrative of humans collapsing into chaos, replacing it with an entertaining story about family, feminism, and the importance of community. There are also so many great feminist reimaginings or reinterpretations of fairy tales and folklore (by writers like Robin McKinley and Angela Carter, to name just two). Tamora Pierce has made a career out of broadening the boundaries of traditional fantasy, constructing her work around female and queer characters. And (to move beyond fantasy), there’s a whole series of anthologies published by Lightspeed Magazine, including People of Color Destroy Science Fiction, Women Destroy Science Fiction, and Queers Destroy Science Fiction, as well as the upcoming Disabled People Destroy Science Fiction anthology coming up from Uncanny Magazine, all filled with fiction by writers from underrepresented minorities which participates in this process of rethinking and playing with science fiction conventions.

All of which is to say: don’t despair if you find you have to set aside some beloved classics from your past. There are so many wonderful new works out there, or authors you may not have discovered yet. And we as a community can help each other with suggestions, ideas, and recommendations! So, I’d love to hear your thoughts on all this:

What books have you had to abandon? Which issues make a book off limits for you personally, or difficult to recommend to others? What are you reading that’s a breath of fresh air? What are you working on in your art that’s wrestling with problematic art you used to love (or always hated)?

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.