When Clare arrives in Havana Cuba for the Festival of New Latin American Cinema—giving a different name to every other new acquaintance and becoming stranger to herself with every displaced experience—it’s nothing new to her, not really. As a sales rep for an elevator company, Clare is used to travel and to interstitial places. She loves the non-specificity of hotel rooms and thrives on random encounters. What she doesn’t expect to find in Cuba, though, is her husband Richard: five weeks dead, standing tall in a white suit outside the Museum of the Revolution.

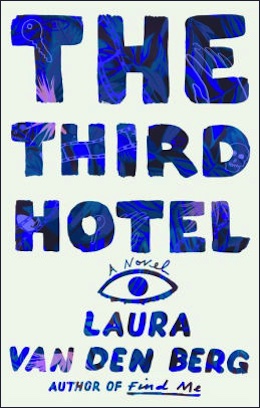

What follows in Laura van den Berg’s novel The Third Hotel is a reality-blurring rumination on the power of grief and alienation. Interspersed with Richard’s scholarly writings on horror movie tropes, and with Clare’s reflections on her own past and identity, the novel inches further from an explanation of her haunting with every step it takes towards her confrontation with it. Lush in description and psychology alike, The Third Hotel is a literary horror novel that will haunt you long past its final page.

To offer a plot summary of a novel so psychologically real and narratively unreal is to do it an injustice. Clare sees a ghost and chases it. She spends long hours reflecting on her relationship with her husband. She meets some movie buffs and visits a quantum physicist to discuss the afterlife. But above all, she and the reader alike experience the event of the haunting, not in fear and revulsion—though those emotions are certainly present—but in disorientation and sorrow.

Beyond the novel’s ghostly husband and zombie movie viewings, these horror elements are mostly drawn out in Clare’s character. She is not your typical protagonist—she moves in a haze, often towards no particular goal; is cold and dishonest more often than not; and her moments of revelation are not cathartic (grief, after all, is never solved by a single moment of self-awareness). Not to mention, of course, her love of anonymity. All this dissociation and desire for non-identity make Clare’s interactions with the world uncanny and tense, and create a tone that drives home the horrors of loss better than a single ghost ever could.

In an early scene of the novel, one of the directors at the film festival explains the purpose of horror movies. It is:

…to plunge a viewer into a state of terror meant to take away their compass, their tools for navigating the world, and to replace it with a compass that told a different kind of truth. The trick was ensuring the viewer was so consumed by fright that they didn’t even notice this exchange was being made; it was a secret transaction between their imagination and the film, and when they left the theater, those new truths would go with them, swimming like eels under the skin.

Rarely in a novel does an author provide a mission statement so early or succinctly. The Third Hotel doesn’t just take away its readers’ compasses—it takes away its protagonist’s. Travel as a backdrop for horror may not be new, but van den Berg makes the estrangement and loneliness inherent to travel more psychologically real and affective than most. The scenes in Cuba are of course terrifying—a ghost is involved, after all—but flashbacks to Clare driving through the flat, empty expanses of Nebraska, and lying naked and awake in the dark of a hotel room, are equally likely to swim like eels under readers’ skin.

Buy the Book

The Third Hotel

The Third Hotel is a muddling not only of the horror genre, but of the Unhappy Straight White Middle Class Marriage backdrop that genre readers often criticize in literary fiction. The most obvious and important distinction is of course that the professor husband does not speak for his wife—no matter how often he seems to try to, through his writings, his reappearance, her memory. Clare pushes against his theories on horror, first in conversation and then in enacting her own narrative. The “final girl,” the sole survivor of the horror movie plot, is not reduced to her strength and masculinity in The Third Hotel, but instead a survivor that mourns, that makes meaning, that deals with the aftermath of tragedy.

I was amazed by Laura van den Berg’s prose and deftness of expression in this novel, but it’s hard to say that I enjoyed it. It makes for an unsettling reading experience, and often an anticlimactic one. It is perhaps more weird fiction than horror, more Oyeyemi than Lovecraft (though it’s undefinability in both genre and resolution are more strength than weakness). Perhaps sitting alone in my apartment was the wrong way to read it, though. If I could revise my experience, I’d have read The Third Hotel on a plane, or in a diner far from home, surrounded by strangers. I think perhaps that in that air of unfamiliarity, its story would have struck more true.

The Third Hotel is available from Farrar Straus & Giroux.

Emily Nordling is a library assistant and perpetual student in Chicago, IL.