From the wondrous mind of Brooke Bolander, the author of The Only Harmless Great Thing, who “shares literary DNA with Le Guin” (John Scalzi).

After the world’s end, the last young human learns a final lesson from Earth’s remaining animals.

Pretend you are the land. Pretend you are a place far away, the last vibrant V of green and gold and tessellated rock before the sea and sky slither south unchecked for three thousand lonesome turns of a tern’s wing. Once upon a time the waters rose to cut you off from your mother continent, better independence through drowning. Some day soon, when the ice across the ocean turns to hungry waves, all the rest will follow, sliding beneath an oil-slick surface as warm and empty as a mortician’s handshake.

But that does not concern us—yet. You are the land, and today you are here to bear witness to a story four million years in the telling as she closes her eyes for the final time, striped haunches slowing their rise and fall as entropy hoists another tattered victory flag.

Thylacinus: from the Greek thýlakos, meaning “pouch” or “sack.” You have made her into your own image, a unique beast neither wolf nor tiger but its own striped singularity. No one at the zoo is qualified to sex such a creature. They dub her Benjamin, short omnivorous ape jaws unequipped to pronounce her true name even if anyone ever thought to ask.

The cage is very hot. There is no shade. When night falls there will be no shelter against the unseasonable cold. She paces and pants, her shadow writing the future across concrete in angular calligraphy. Beyond and through the chicken wire bland faces peer, unable to make any sense of the warning in her trot, the glassiness in her staring eyes.

But you are the land, and you read the message loud and clear: a missive from the place between being and not; a signal from the space between the final breath and whatever comes after.

Auntie Ben pats makeup over her stripes every morning. The last neighbors moved on years before, the only folks left to see are Martha and Doris and Linnea, but Auntie Ben, she has her habits. In the end, the only sense you have to make, she tells Linnea, is to yourself. And so: delicate little dabs along the lean, dusky line of her jaw, up the cheekbones sharp as taxidermy knives, all the way to her forehead, where hair the color of dirty sand dangles listless, fabric on barbed wire. Nobody knows where she found the powder. Nobody asks. Maybe it was waiting when the three arrived, like the vanity and the three beds and the yellow farmhouse itself.

“Every mammal’s got stripes,” she says. “Even you. Fella named Blaschko found ’em. Somewhere back along the line, your people took ’em off as easily as I shuck my own skin, buried them in a cigar box out back. If you could find that box again, you’d find your stripes, sure as fleas and fresh blood.”

Linnea asks Doris if this is true. Doris is stout and cheerful and most likely of the three aunties to give a true answer. She cooks, she straightens, she drives the pickup to what passes for a town these days to pick up supplies. She does not work on the ship. She lacks the imagination, she says; she was never that great at flying to begin with. The little cedar chest at the foot of her bed more often than not stays closed.

“There’s no telling with Benny,” she says, scratching at her round, flat beak of a nose. “She’s always been a reader, that one. You don’t look like you got stripes to me, though. Humans come in all shapes and sizes—most of ’em hairy or hungry, terribly hungry, how can such skinny things gobble up so many?—but I never do believe I’ve seen a striped one. Then again, not a lot of them around to study anymore ’cept you, little chick.”

She doesn’t bother climbing to the roof gables to ask Auntie Martha, staring sadly up at an empty fading sky as bronze-and-violet as her hair. Instead, Linnea wanders back inside and stands alone in front of the vanity mirror, searching for invisible stripes. The light through the bedroom curtains is a washed-out yellow, like paper or preserved hide or the end of a long, hot day.

They never say how they got together, Linnea’s three aunties, or where they hailed from before finding her and feeding her and fetching her home, lucky orphan among grubby roadside hundreds. She doesn’t remember faces before theirs. There was a gas station with busted windows. There was a little scratched spot in the dirt beneath the old pumps where she slept at night. There was potato crisp grease, tangled hair, and the occasional sandstorm. Beyond that, Linnea’s memory is a skull picked clean; shake it and hear leaves rattle inside.

That’s okay. Now is good. Back Then was probably not-so-good. And as to what lies ahead…No. Linnea keeps that lonesomeness locked down tight as any auntie’s chest. Now is good; the rest doesn’t matter.

Endlings make for strange bedfellows, Auntie Ben often says, pounding away at sheets of rusted tin atop the rickety rope ladder. She keeps a red bandana faded to the color of bared gums tied around her forehead. Her overalls are so stitched and crookety-patched (Doris does her best, but her fingers are too thick and strong and her eyesight too bad not to mangle such tiny work) they look like a quilt tossed over her long, lean self. She keeps all her tools in a denim pouch against her belly, saws and nails and a gone ghost forest worth of toothpicks forever tumble-scattering to the dusty ground far below. Auntie Ben has a lot of teeth to keep clean. When there were fresh bones to gnaw, she says, wistful, there was no need for toothpicks.

“Wombat feet,” she says. “Those always did the best job. Itty-bitty little bones, but sturdy.” A sigh, a shake of the head. Back to soldering a seam, goggles pulled safely down, impossible jaw firmly set.

Auntie Martha mostly draws star charts, sitting atop the farmhouse with paper and pen. Sometimes she sings. Her voice is croaky and harsh and the words make no sense to Linnea: endless repetitions of the same sound tunelessly unreeled, keeho keeho keeho kee! Sometimes she cocks her head afterward, almost like she’s waiting for a response. Nothing ever halloas back. Just the windmill creaking, the screen door slamming, the bang-bang-bang-bang of Auntie Ben’s hammer smashing dusk’s purple hush to pieces like a carelessly laid egg.

Pretend you are the sky. Pretend you are a sky the faint peach and dusty slate of a dove’s wing, folded protectively over darkening fields of corn and cities where yellow lights wink on like punctilious fireflies. Some day soon you will wither and broil. Those newly-hatched smokestacks on the horizon will slide beneath feather and skin and subclavius muscle with a hypodermic’s lethal care, a payload of jaundice injected with a belch and a billow, and the resulting buildup of toxins will ensure nothing bigger than a botfly ever darkens your horizon again. Your decay will smother the world, a dead bird huddling over an empty nest.

Soon, but not today. Today you are full of life—screech owl and nightjar, cranefly and bat. They know the spaces between stars. Even the ones locked fast in cage and crate can feel the wheel turning, seasons brushing shoulders on the subway. Away I must be going, they say to the bars and the locks, the cold iron that batters the breath from their hollow bones. I’ve had a lovely life here, but spring waits for no one, and I really must insist—

Even when all the rest are gone, millions blasted from your breast and returned as smoke, she feels the pull and calls to you. Every autumn for twenty-nine years, right up until the day of her stroke. The zookeepers hang the name of a dead president’s wife around her foot like a wartime message, hoping for domesticity, but she is still Ectopistes migratorius, traveler in name and nature.

She hears the sound of phantom wings and hurls herself against the ceiling, desperate to take her place in the thunder. Her tired old body is the color of a bruise.

I’m coming, she whirrs, again and again. Wait for me! I know which way to go!

Buy the Book

The Only Harmless Great Thing

“Once upon a time,” Auntie Ben says, seated beside Linnea’s bed, “there was a cage. But that cage is rusted all to hellfire and back now, and the men who built it are bones in the dust so dry not even a dark-flanked yearling would stop to take a sniff. Nobody remembers a damn thing about those men. Nobody remembers their chickens, their guns, or their stupid cage with the concrete floor. But they remember us, my little naked joey, sharp-toothed pride of my pouch. We were beautiful and strong. Our stripes left long shadows across their minds. There were plenty left to remember us, but who will be left to remember your kind?”

“Once upon a time,” Auntie Doris says, “—and oh, it was a long time ago, fresh fruit and green grass and the Rats and the Dogs not yet come—there were nests! Nests on the ground, can you imagine, beneath trees that dropped nuts so close you didn’t have to stretch your neck out far to take them. We laid our eggs where we pleased. But then the Men came—yesyes, and the Rats, and the Dogs, the terrible slavering Dogs—and the guns went bark bark bark all the live-long day. Our nests and our eggs and our fine fat selves, we dwindled down to nothing.

“But do they remember us now, sweet milk of my crop? Bless my gizzard and claws, they do! Those hungry men stopped being hungry, oh, ages ago, and their guns and their clubs rotted like rained-on feathers. Nobody remembers much at all about them and their growling bellies, but they remember our name, you’d better believe they do. There were plenty left to make our name round and fat, but mercy, who will be left to remember your kind?”

“Once upon a time,” Auntie Martha says—her voice is so soft you have to bend your eardrums low to pick up the words, a halting thing much gentler than her evening song—“we were a thousand. We were a million. We were many, and we blotted the sky with Ourselves. We flew where we pleased, and where we flew was pleasing. We followed the starmaps, the pull in our heads that said Go here! Go here!

“But the guns brought us down, by the thousands and the millions and the many. We lost the stars. We lost ourselves. But d’you think, little squab of my breast, that they could ever forget the sound of that many wings blotting out the sun? There were plenty of mouths and memories to pass on the beating of a million wings that was our name. As to who or what will be left to remember your own kind, dwindling with no wings to bear them away…”

Auntie Martha shakes her head.

“We were many too, once,” she repeats, barely a whisper. “I really am sorry.”

Linnea has a voice, too, but she doesn’t use it much. The inside of her head is a safe place, full of futures that will never happen so long as she keeps her words under lock and key. You open doors when you say things. There’s no telling what will come out of them, or where they may carry you off to in their jaws. Linnea likes it here; she has no desire to be stolen away. The days flash by unmarked—fur-yellow, feather-purple, rust-red—and change comes in slow, sneaky bursts, the space between looking away and turning back, moments of distraction. The earth grows a little more cracked. The ship teeters a little higher into the brassy sky. The wars Elsewhere, according to the dying radio in the kitchen, are running out of bodies.

“All things run out eventually, unless you outrun them first,” says Auntie Ben. Her shadow isn’t a woman’s and leaves no question as to her identity, falling snout-to-tail down the wooden work platform. “Your people were never canny enough to plan for the one nor fast enough for the other. Poor sods. Be a love and fetch me that pair of metal shears from out the kitchen, will you?”

Linnea does as she’s told, crossing the hardpan between farmhouse and building site at a gallop so the ground doesn’t burn her bare feet. Her own shadow is small and knobby-kneed and very much human.

Pretend you are the sea. Pretend you are a life-filled veil of green and gold and black and blue covering 70 percent of the land and most of its mysteries. Some day soon you will choke on refuse. A growing knot of bottles and bags and tires and zipties and rubber duckies and microbeads and bright plastic bric-a-brac will catch fast in your throat, suffocating all life from your deep places. You’ll bloat like a dead thing, an albatross chick’s belly packed tight and stretched grotesque with all the indigestible junk you’ve been fed. And when the last coral has withered—when the final whale has sung her question to an empty abyssal plain and there’s not even a hagfish left to mourn her passing—you will rise primeval, stinking of pig effluent and rotting fish, mercury and motor oil, an entire undead ecosystem marching on the cities of the coast.

Soon, but not now, and not for many ages yet. Today you are bursting with so much life the men who ride your waves in their great wooden ships cannot conceive of an end to it all. They match the seeming limitlessness of your largess with an equally insatiable hunger, seeking and searching and grasping. The world has never seen anything like it. There is no time to prepare; blink and they’re pulling ashore with axes and dogs and fire. Sink their boats and six hundred more will follow. Flood their encampments and they simply sail to the next island, rats and pigs ravaging in their wake.

You have protected this rugged little hunk of jungle and sand well. The animals here are special, coddled by your sheltering blue arms until they barely remember what fear is. The birds nest on the ground and lay their wings aside unused, for of what possible use are wings when there’s nothing to flee? Round and happy is Raphus cucullatus. Round and happy you would have them forever, your little flightless flock, but you cannot rage hard enough or squall fierce enough to stop what’s coming.

Hobnailed sailor’s heels in the white sand, clomping up the waterline. A crunch and a thud; the first pair of curious eyes dimmed.

The killing doesn’t stop for years. Axes ring and the fires burn and the rats and the pigs pick up where the clubs and machetes leave off, shattering eggs and snatching chicks even after the first settlers grow bored and Abel Tasman bobs away to wreak civilization on other untouched shores. They eat until there’s nothing left of the flock but white sticks in your surf.

They capture a few of the young birds alive and send them back across your waters. The last will be put on display as a public attraction, a curiosity kept in a dank, dark little chamber at the back of a shop. She will huddle into herself, feathers fluffed to ward off the chill of this gray place so far from her tropical homeland. The people who pay their pennies to see her will laugh at how round she looks, how plump and silly and vacant-eyed.

Nobody left to speak through the kitchen radio. No more words. What’s left of the nearby town dries up with the rain. They take what they want from the abandoned shops and load it into the pickup and there’s not a soul left squatting inside or out to squint twice at the theft.

Linnea snoops in the cobwebs and cupboards while they loot, because once upon a gas station that was how she survived and sometimes she misses the taste of greasy crisps and dime-store jerky. There are newspapers, but they’re all from a long ways back and fat as ticks with bad tidings. There are old weather almanacs, but past a certain printing they all run a woeful rut into the dirt: rising tides, rising dust, rising temperature lines the color of sunburn. There are photographs, but they’re not from a world Linnea knows. There are clocks, but nobody’s left to wind them.

There aren’t any crisps left, either. Just plastic crinkling in the creosote bushes, as mournful in its own way as Auntie Martha’s evening songs. Linnea licks the sweat salt off her lips as they drive home, the three aunties crammed into the cab and her alone in the bed with the wind and her thoughts and the wide-stretched sky.

The first passenger is waiting when she runs downstairs for breakfast, seated at the table next to Auntie Ben like that’s the way things have always been. A muscular, sturdy, broad-shouldered lady, with slate-gray hair and a big sharp nose and tiny red-rimmed eyes behind wire spectacles, thick lips drooping southward in a permanent scowl.

“This is Fatu Ceratotherium,” says Auntie Ben. “She’ll be staying with us for a while, helping out with the ship until it’s done.”

Fatu squints down at Linnea, snorts, and continues turning the pages of the book she holds, muttering something about humans under her breath. Linnea is glad to excuse herself and escape outside. Nothing’s changed there overnight, at least. Since it’s early and the ground is still cool she visits the gorge behind their property, something hard and hot bubbling beneath her chestbone.

It’s a new feeling. Change has planted it there, and she feels more change building where she can’t quite see it. Good things—crisps, soft beds, kindly aunties who keep your hair free of snags—can never ever stay when change is on the move. If it was a thing she could bite, she would bite it. If it was a thing she could throw rocks at, she would chuck pieces of flint until her arm fell off. But there’s nothing to do but wait for whatever is coming.

So she screams.

She shrieks into the canyon until the echo makes a pack of her, big and mean and capable of keeping things the way they are forever. She shrieks until her throat gets raw inside and the sun heats the ground beneath her enough to be uncomfortable. She doesn’t cry, because that’s a waste of moisture and she’s frustrated and angry, not senseless. But she yells. She even uses a few of the more interesting words she remembers from the walls of the gas station restroom while she’s at it. And it does make her feel a little better, eventually. Not much, but enough to ease the feeling in her chest.

“They’ll never come back no matter how loud you call, you know.”

Another change: Auntie Martha is off the roof, right in the middle of the day. She lights a hand on Linnea’s shoulder, delicate but with a surprisingly strong grip.

“No, they’ll never come back, little squab of my heart,” she continues in her gentle singsong. “The nest is scattered and the shell is crushed and in the case of your people, they did it to themselves. But it…it does feel good to try, doesn’t it? You always hope something other than your own voice will fly back. And isn’t it always worth trying? Just in case?”

They’ve done their best, her aunties. There’s a gulf between them that no ship can cross, but they’ve tried very hard, and they love her despite her humanity. Linnea gropes for words, a shape to fold her feelings into. Her voice sticks like a rusted pump drawing up dust from an empty well.

“If I call,” she says, “will you come back?”

They watch the question drift to earth together. Auntie Martha sighs, soft as eiderdown, and wraps her arms around Linnea.

“Oh, little squab. Little naked thing.”

More passengers arrive—not just two-by-two, but in ones and threes and severals, all more or less shaped like human women. The radio crackles static, the horizon sizzles with heat, and the farmhouse fills with the noise of idle waiting room chatter. Figures with shadows like frogs and parrots and long-necked tortoises loiter on the porch, smoking and waiting for sundown. Some help Auntie Ben with what’s left of the ship’s construction, hammer-hammer-saw-slam-bang. Others walk the halls at night, pacing with an impatience you can feel sparking off their soles like blue lightning. The air, Auntie Doris says, feels like a chick is pecking gentle-like on the other side, looking for the best place to lay into the world’s shell with its egg-tooth.

“I still don’t see why it has to be a ship doing the cracking, though,” she adds, looking as disgruntled as she ever gets. “I don’t trust ships, even the kind that don’t go on the water. No telling what a ship will unleash, no no no there never is.”

Linnea tries to stay out of the way, but it’s hard when there are so many others around. She takes to sleeping on the roof with Auntie Martha, whose skinny fingers are an ink-stained blur now from sundown to first light as she makes her charts. Scritch-scritch-scritch goes the fountain pen, spinning delicate spider silk lines between stars. The house below them hums hot, creaky impatience in its sleep. Further out in the yard, listing in its scaffolding, the ship looms black and blue.

“Nothing has an ending. Not really.” Auntie Martha says little while she works, which means she says little at all these days. When she does bother speaking, Linnea listens, hoarding every word against future silences. “Hatching is not the end of what lies inside the egg, only the end of the shell around it. There’s no flight without the shatter, and no flock without the flight. What we’re made of will go on. A fledgling in some other place and time will look up for guidance and maybe see the path we leave behind, even when all of this as it is”—she flutters her free hand at the darkened desert—“dries and blows away. Change is comforting, in that way.”

Linnea casts a wary eye at the night. She tucks her knees in tighter beneath her chin.

Pretend you are the wind. Pretend you are the inhalations and exhalations of the land, the breath of tortoise and tree twisting windmill and grass blade alike. Some day soon you will kill everything you touch, spreading a mushroom cloud’s poison seed from desert to delta to distant island. Death will fruit as heedlessly cheerful as any invasive species mankind has ever sown, unconcerned with distance or climatological delineations, and the world will slowly return to silence. All the world’s a graveyard. Like the last soldier in some grim and cautionary fairy tale, you are tasked with whistling past its gates forever.

Soon—very soon, the thoughtful pause before a clock’s hand flicks to midnight—but not yet. Today there is still life, although it’s a scraggletailed, desperate kind of thing, struggling to grow through a coating of red dust. You blow past caravans of ragged scrabblers, towns and communities clinging to civilization like cubs clutching at a dead mother’s fur. You sweep through pockets of memory and unreality. Ghosts and grit tumble down empty highways. Sometimes they clump into things with form and will; old spirits crossing an older landscape, psychopomp trompe l’oeil. The border here is very thin. History overlays it all like a second skin, a hidden shape the eye has to unlearn everything to recognize. See the beast with stripes like a cat and jaws like a wolf? See the glaciers that carved the horizon? See the people who lived here before, their homes and their handprints, the blood they spilled in the sand?

Old roadsigns rattle and dance as you pass. Junk food containers whirl. Beside the long black scar of the highway is a gas station.

You pause to brush the little girl’s bangs back from her face. She’s lost in concentration, momentarily distracted from hunger by the task at hand, sunburned forehead creased. Her hands work the old candy bar wrapper into triangles, pyramids, arrows, flaps and furrows, halves and planes. An alchemy of geometry, transmuting garbage into a kind of escape.

At last she finishes her spell. It sits stately in her palm for a moment, a crinkled paper bird smudged by dirty fingerprints and time. She lifts her hand to you as you pass and you take the little gift, touched by the gesture.

“Goodbye,” she says. You keep on moving as always. The paper bird soars. “Goodbye.”

The farmhouse is at full capacity, as full of visitors as it can manage—restless bodies crammed cheek-to-jowl, wood-and-brass chests of varying sizes stacked in corners and jammed beneath beds. Linnea isn’t the only one who sleeps outside now. They spill down the porch and into the front yard on rude pallets, shaking sand from their ears and hair when the brassy bright mornings come. It’s very hard to avoid their eyes; there are so many of them, and they are all so watchful of her two-leggedness. The ship—finished, Auntie Ben says, as it’ll ever be, and as it’ll ever be will do just dandy for their purposes—strains at the sky. The nights grow cold and brittle.

Linnea lurks around the edges, hugs corners, and spends most of the days remaining with a fist-sized knot churning in her stomach. The passengers move their trunks and their bedding to the foot of the ship. The farmhouse deflates a little. The knot in Linnea’s stomach stays the same; deep in her heart she knows what’s coming, although not one of her aunties says a word. When their chests finally vanish from the bedroom as well one afternoon, it’s almost a relief. Three square holes in the dust at the feet of the three neatly made beds, hardwoods darker there than their surroundings. Like shadows burned into pavement, or the white chalk outline of a hand on blood-red clay.

She has no trunk, no locked box with her name on it and her true skin inside. Her shadow is nothing if not honest. It drags at her heels as she walks—no running this time—down to the gorge. There is no memory of being left behind in her head, but there is a feeling, and it has all the contours of something well-worn and familiar.

Someone is already at the canyon’s edge when she arrives. Big, broad-shouldered, gray-haired—Fatu. Linnea thinks about leaving. She thinks too loudly and too slowly, and Fatu notices her. Linnea waits to be ignored, dismissed, or snorted at. Fatu’s never had time for anything much other than working on the ship, and no time at all for a human child, no matter how beloved of her hosts. After their first meeting Linnea had done her best to stay out of Fatu’s way. Up until today she had proven pretty good at it, too.

Instead, Fatu wordlessly waves her over with a blocky hand. They sit together in silence, big and little legs dangling over the gorge’s lip. To their left the sinking sun is an angry, infected red.

“They lied about my kind when they first saw us. Dumbest damn thing.” Fatu doesn’t take her eyes off the horizon as she speaks. Her voice is a rumble Linnea feels in the unmapped interior of her chest. “This was Wayback, before cameras or jeeps or automatic weapons or any of that sort of shit. You know how many horns they said we had, when they sent word back home? Or where they said we had them growing from? Some peabrain blinder than my grandam drew a picture, and that picture, it grew some legs. It ran far. Soon everybody thought the lie was truth, all on account of one silly, stupid drawing. Nobody there to correct them. Nobody around to tell the true story, and it wasn’t as if we could speak for ourselves.” She halfheartedly flicks a pebble into the chasm. “Lies are like ticks. If you have no birds to pick ’em off, they breed, and they suckle, and they turn your world sickly. Your vastness shrinks. Your skin gets thin and pale. Soon, all you’re left with is…unicorns.”

Fatu spits this last word from her mouth like a nettle. She chews on her bottom lip for a moment, brow furrowed, nostrils flared. Linnea waits.

“A unicorn is a fine fiction,” she continues, eventually, “but it isn’t me.”

On the final night, they build a fire in the ship’s shadow. They open their chests—their trunks and their suitcases, their valises and chiffoniers—and they tell stories.

A dark-skinned woman with green hair and curved lips is the first to unlock hers. Inside is a cloak covered in emerald feathers, neatly folded. She pulls it over her shoulders with an eye-dazzling flourish. In the darkness between blinks—in the waver of heat off the bonfire—she melts and changes. Now she is a green and red parrot, perched on the trunk’s open lid.

Her audience leans in.

“I was a hundred,” she says. “I was a million, although I did not know what million meant. Our forests were as green as our feathers, and just as numerous. The fruit was sweet, the chatter of my flock sweeter. ‘Silence’ was another word we did not know the meaning of, and we were happier for it. Loudest of all those millions was my mate. There was no nut her beak could not shatter. We raised many clutches together, fine and strong and shrieking.”

She lets that picture hang in the air: a green place filled with the screams of a happy, prosperous people, wings flashing in the dapple. Linnea, who has only ever known red dust, cannot see it no matter how hard she tries.

“They cut the trees down, one by one, and my people soon followed,” she finishes. “Those hills are bare now. They know the meaning of silence.”

A pause, and the parrot flies into the fire. Only her shadow emerges from the flames. It flaps into the high scaffolding surrounding the ship, lands, and waits.

The next to step forward is sharp-faced and angry and almost as short as Linnea herself. She yanks her furry brown hide from inside its chest—no nonsense, no pause for dramatic effect. A blur and a noise like teeth clicking together and a shrew glares up at the crowd with eyes like glass splinters, daring interruption.

“THE SONS OF BITCHES PLOUGHED UP MY BURROWS!” she yells. If her body is small, her voice is more than loud enough to say what needs saying. “THEY BUILT APARTMENTS THERE! APARTMENTS! GOOD RIDDANCE TO THE LOT OF THEM! I HOPE WHAT’S LEFT OF THE BUNCH ENJOYS THE MISERY THEY’VE MADE!” She shoots Linnea a triumphant, bitter look and stomps one of her little feet for emphasis before skittering into the flames. Her tiny shadow is swallowed up entirely by the ship’s massive one.

There are stripes on the cheeks of the third, and an expression that says she’s never dabbed makeup over them and might sooner cut off her own head than entertain the thought. She holds her chin high as she changes, higher still as she speaks. Her voice is a razor wrapped in velvet.

“They took my forest,” she says. “They took my prey. They took my people’s skins. Not my skin, but that didn’t matter too much in the long run, now did it?” Her tail-tip swishes. “Their fear was deadly enough, but their admiration was what crushed the windpipe. There’s nothing worse for continued survival than their wanting to be like you—to touch you, to possess you. Once they get it into their heads that you’re ‘special’…”

The tigress shakes her head disgustedly. She stalks off to meet her fate.

One by one they stand and have their say. One by one the cluster of shadows beneath the ship’s bulk thickens. Scale and fin, feather and fur. A woman with black and yellow hair and a voice like many voices buzzing together. Leather-faced, leather-skinned aunties with slow-spoken, toothless mouths. Enormous Fatu. The fire takes them all, changing them, and their stories are all different and yet, at the heart of things, all the same. Linnea watches with growing apprehension, fear coiling inside her. She cannot decide which is more terrifying: walking into the fire or being left out of it.

The sky lightens. The group thins. Three left: Auntie Ben, Auntie Doris, and Auntie Martha. Linnea wants to cry out NO!, but something solid seems lodged in her throat.

Auntie Ben goes first. With a fond, wry smile, she retrieves her skin. A long-jawed, rangy thing, neither wolf nor tiger, with stripes on her ragged flanks: that is the true shape of Auntie Ben.

“I’ve told my story about as often as anyone cares to hear it,” she says. “We were strong and swift and lived freer than scrub seed. Men came. They did what men carrying guns do. Just to add insult to injury, they stuck the last of us to die in a bloody concrete cage as a way of saying ‘sorry.’ I’m tired of blathering on about that, though. If it pleases you all—hell, even if it doesn’t—I’d rather never think about it again. I’d rather kick sand over this dead place and head for the stars, where other somewheres might be in need of fur and feathers and sharp, smart jaws full of teeth. Chicks leave the nest and joeys leave the pouch. It’s just about time for all of us to do the same.”

She doesn’t step into the fire. Not yet. Instead, she pads across the open space, stripes rippling across lean muscle. She keeps on coming until she’s so close Linnea can smell the dusty musk and fur scent of her. It’s a wild reek—which makes it slightly unnerving—but it’s also Auntie Ben, which makes Linnea abruptly sob and fall forward to hug the rangy creature around her rough neck. Auntie Ben allows the mauling, good-natured as always.

“I know you’re afraid of changing, little one,” she says softly. “Your people never were any good at it, and you’ve seen how that turned out. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say that’s why you’ve got no skin of your own, poor naked mite.” A long pink tongue flicks out to touch Linnea on the cheek. “But whether you go or stay, change is coming for you, and it can either be the one you choose or the one you don’t. Which is it gonna be? Think you can manage the trick?”

Linnea tries to say yes. She tries to mean it. But the fire and the unknown behind it and her fear of both (she’s so afraid, she can’t help it, her knees are shaking and they won’t stop) turn her attempted “yes” to a lie, and the lie clots sour and solid so that not a word can get around it. Auntie Ben watches her struggle, unable to offer help or assistance or meaningless, soothing words that might also be lies.

Gently, firmly, she pulls away and steps back.

“It’s up to you,” she says. “We’ve done all we could.”

The creature Linnea knows as Auntie Ben turns and trots into the fire. Her shadow gives Linnea a final featureless look over its shoulder before taking her place in the crowd of shades.

Auntie Doris comes next, as serious and wide-eyed as Linnea’s ever seen her. A click of the lock and a snap of the hinges and here’s her own true self: a thick-beaked, long-necked, goggle-eyed bird with a fat, squat body and wings more like suggestions than anything approaching useful appendages. She takes a look at herself—the stout legs, the powerful claws—and chuckles fondly.

“Round as an egg, round as an egg, bless my bottom feathers. And what better way is there to be? Flight isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, no no no. I see plenty of them’s got that power standing in the ranks, and you see how well that served them. They’re passing on through the fire, same as I.” A firm nod of the bulbous head. “I admit to mistrusting fire. When the men came to our lands they carried it, and I can still remember the smell of all my aunties and uncles and cousins a-roasting over it. But they’re all gone now, and so are all those hungry, hungry men. Nothing left but my poor Linnea, and we raised her better than all that, didn’t we, girls?”

She waddles closer. Linnea hugs her as well; soft feathers over surprisingly hard muscle, like a silky, affectionate fireplug.

“You learn things, being so low to the ground,” she says. “You learn to be sturdy. You learn how to appreciate the earth you’re planted on. Nobody ever knocked me down with any club! If I settled my bottom, it was always my own decisioning. That’s important. Whatever you do, you just remember that, love. You settle your bottom where and when you feel like it. We’ll understand if the fire is too much to ask, but oh, we will miss you.”

A final affectionate butt of the head, a long, fond look, and away she goes, at as stately a pace as one of her kind can muster. She flinches at the fire’s edge—remembering those earlier fires, maybe; the dogs and the rats and the hungry sailors—but only for a moment. Auntie Doris is stronger than she looks.

Auntie Martha’s trunk is lined with yellowing maps of the stars, and the feathers of her cloak are the slate-and-peach of the pre-dawn sky. She settles on Linnea’s shoulder with a whistle-whirr of wings.

“We were more like your kind than all the others, in our way,” she says, close to Linnea’s ear. “So many of us we blotted the sun and stripped the branches. But we exist to learn, and to change in the learning, in the hopes that some day we may find ourselves changed enough to tell our stories and tell them honestly, no matter how much that may sometimes…sting. Then we can become something else, and fly on.” Her claws dig through the thin fabric of Linnea’s shirt. “I am uncomfortable with all this talk of decisions. There’s nothing wrong with needing more time. Hatchlings grow their feathers when they will. Do you feel your people are ready to have their story told?”

Linnea looks at the shadows and the rocket. She stares into the fire. All she knows is potato crisp wrappers and garbled voices on the radio. The aunties gave her love, but in their love they neglected many things.

“There are some things that cannot be taught, only learned,” Auntie Martha says, as if hearing the thoughts rattling around in her head. “That was not our story to tell, little fledging. We’re ghosts, and you are still alive, but we love you, and that makes the letting go hard. No one—not even those you care about, neither I or Ben nor Doris—can or should force you into a change you aren’t prepared for. It has to be your own decision, in your own time.”

She fluffs her feathers and rubs her head against Linnea’s cheek.

“Remember our stories while you learn your own,” she whispers. “I left star-charts for you; they’re in the bedroom in a box beneath my bed. I carry my own in my head, the same as my people always have.” A note of pride. “Catch up when you’re ready, and no sooner. Be good. Remember we love you.”

Shades marching two-by-two onto a shadowy ship—shadows of tiger and thylacine, dodo and dingo, elephant and sharp-horned rhinoceros. They hop and fly and pace up the gangplank in silence. The fire beneath them dies to embers as the light in the east grows and the last disappears inside, the rusted old hatch slamming shut behind them with a clang.

Nothing happens, at first. Then there’s a slow rumbling from within the rocket’s guts, a rust-rattling, bolt-testing shudder that grows and grows and grows until the entire ship and all the ground around-abouts it are shaking like a penny in a tin can. The first red rays of the sun set fire to the scaffoldings and fins, the soldered seams that patch the scavenged eyetooth-length of the thing together. Orange dust rises like smoke. The long, pointed shadow at its base jitters faintly.

The ship begins to topple over. At the same time, its shadow pulls itself free of the dusty ground, ascending with a noise like a hurricane wind made up of the calls of every animal to ever creep or crawl or flap or low, a joyous, cacophonous menagerie. It lifts higher and higher, charging to meet the dawn as, far below, the ship collapses completely. The air is full of sand and twigs and old litter picked up by the whirl—candy wrappers, plastic bags, feathers. Chunks of scaffolding tumble-bang to earth end-over-appetite, adding their own clattering boom and roar to the morning as the shadow pulls away. It is a cloud—a bird—a mote swimming across the eye—and then it is nothing at all.

The triumphant menagerie song fades to an echo. A trick of the wind, occasionally interrupted by another piece of the ship’s struts coming down with a tooth-rattling thud.

Goodbye.

Every morning she gets up and brushes her own hair, makes her own bed. She eats a breakfast of whatever she’s scavenged the previous day. There are no potato crisps, but the aunties taught her long ago all was left that could be plucked, pecked, swallowed, or snapped. If the weather’s good, she takes the pickup out looking for pieces of story—diaries of neighbors, scraps of old newspapers, history books. If it isn’t (and frequently it isn’t; the storms grow worse as time spreads like a puddle), she spends her afternoons huddled in the root cellar, thinking about everything she’s learned.

She watches the seasons turn until there are no more seasons, just days, hot and identical when they aren’t memorably violent. She outgrows her clothes and takes new ones from the abandoned town. The kitchen radio coughs dry static for a little while longer before dying completely. One night the sky dances with cloudless lightning the color of blood, a crackling red net stretching from horizon to unseen horizon. The next morning the pickup won’t start.

From then on Linnea walks everywhere she needs to go. She wears out every pair of shoes the town’s got left and then her feet get as hard and tough as everything else in the dying world.

Old warnings unheeded, predictions shrugged off, smokestacks belching into the sky. Extinction. She learns new words.

With the pickup broke down, food gets harder to find. Linnea’s ribs are a ladder leading directly to her throat. She dreams of the tastes of all the good things she’s ever eaten—canned corned beef, a soda she found in a vending machine once, the beloved and well-worn potato crisps. She dreams of constellations with stars like stripes along their flanks. She dreams of an airship, a low-swung thing with a sagging canvas belly above and a wooden deck below.

When she wakes from the last, she has a blueprint in her head. She’s no longer hungry or thirsty. She has all the energy in the world, a mind overflowing like a rain bucket with stories.

You’re changing, Auntie Martha might’ve said, pleased. You’re learning, growing your feathers. You’re almost ready to fly.

Saying goodbye stripped Linnea of her fear. Once the worst comes to pass, what else is there to fret about?

Now all her energy focuses on building the airship. It becomes an obsession. She gathers old sheets, pulls the curtains from the bedroom windows, raids houses and boarded-up hotels for their linens. She stitches them all together (when did she learn to sew?) into a giant patchwork bag. It gives her no free time to spend missing the aunties or thinking about food. She sits cross-legged in sandstorms with her needle and thread, head down, turning quilts and blankets to wings. She no longer feels the sun on her back or the hot wind in her hair. All that’s left is determination.

Catch up when you’re ready, and no sooner.

The farmhouse loses its clapboards. The airship gains ribs and struts and a sturdy wooden basket in a cheerful, peeling yellow. Propellers are pried off fishing boats that will never see water again. There are parts of the construction that Linnea cannot recall clearly the next day; a dark spot in her mind’s eye and the patchwork bag is stretched and nailed firmly over the frame and she has no memory whatsoever of how it got there. A feeling of finality builds. It pushes everything else out like a cat expanding to fill a sunny windowsill.

A night comes when the moon is as full and fat and yellow as a disc of dry bone in the sky. Everything is spilled ink and ivory. The airship squats near what’s left of the original rocket, waiting for Linnea as she steps out her front door. Not a sigh of wind disturbs the becalmed world. It’s as still and breathless a night as she’s seen in an unreckoned amount of time—a listening audience, a girl waiting for a bedtime story.

Or a conductor waiting for someone to fish out a ticket. She’s got no skin but her own to draw on; humans traded their stripes for words long ago.

“We weren’t very good at this,” Linnea says to the darkness.

After going so long without speaking or hearing another voice, the sound of her own voice lands like a teacup kissing concrete.

“The man who built this house used to hit his wife. He died a long time ago, before the aunties moved in, but I still know that somehow. I know a lot of stuff now. I know all the things I learned and all the things I didn’t.” Linnea lets her gaze wander over the familiar front porch landmarks—the abandoned wasp nest in the shadowy upper left corner, the pillars sandblasted down to bare, dried wood. She thinks she sees movement out of the corner of one eye. A dark bipedal shape beneath the airship’s bulk, an absence of moonlight clinging to memories of alarm clocks and apple pie. Another joins it, then another.

“I know why me and all those other kids were living around the gas station,” she continues. “I know where all the grown-ups went. I know why they went there, and why they never came back. I know why they stopped talking on the radio, and it’s all…so…dumb. Nobody would listen to one another, not even to the people they loved. Maybe they weren’t scared enough. Maybe they were scared of the wrong things. They didn’t have Auntie Ben and Auntie Martha and Auntie Doris to teach them about stuff and they wouldn’t have listened anyways, but…”

There are so many stories buzzing inside Linnea’s head it’s hard to hold on to the frayed length of her own thoughts. She gropes and pushes aside other people’s memories until she finds the end of it again. The little cluster of flickering shadows around the airship’s hull is thicker now. The patchwork bag shudders and stirs with a faint hiss.

“We weren’t very good at this,” she repeats. “And we took everybody else with us. But we weren’t all bad. We had potato crisps, and ice cream, and we built farmhouses and wrote songs and told stories. Maybe next time will be okay. Maybe we’ll turn into something better at changing once we fly.”

There is a noise—a rising wind, a thousand whispers, a sliding of fabric and a slither of inflating canvas. The horizon in the direction of the abandoned town seems to ripple.

Linnea steps off the porch into the moonlight. She strides across the yard, vaults the fence, and doesn’t stop until the shadow of the rising airship reaches out to swallow her own.

Pretend you are the land—the empty sea-lapped cities with their blank skull eyes, the blasted green glass wastes, the skeletal forests. The desert, as red and uncaring as ever. Do you feel the shadow cutting a nightjar’s swoop across your foothills? Do you see the airship that throws it, nosing noiselessly across the face of the moon?

Ghosts rise to meet the vessel, sinuous as smoke and blue as pilot flames. They cluster thickest over the cities, but even in the empty parts of the world there are always a few hurrying to catch up. The airship moves with the graceful, unbothered patience of a whale hunting for krill. It is a black mouth with a belly big enough for all of humanity, filtering souls from a night that seems endless. No need to rush, it whispers, but even in extinction humans are terrible at altering their old habits.

(Remember whales? Remember nightjars? Remember life in the sea and the sky?)

It takes forever. It takes no time at all. It crosses all the whens and wheres, all the should-have-beens and never-wills. Whoever or whatever stands at the wheel has a steady, tireless hand. The gathering goes on for exactly as long as it needs to, until there’s nobody else left to claim. The moon sets and the stars rise; so, too, does the airship. It sets a course for a constellation shaped like a long, lean predator, distant flickering suns dotting its purple flanks like stripes.

Drifting gently upward

(Remember balloons? Remember letting go of your first in the parking lot of some forgotten bank, tearfully saying goodbye as it climbed and climbed and the sun turned it to a bird?)

distance shrinks its size, taking memories of telephones and coffee tables and radio broadcasts along with it. First kisses, last breaths, friendships and fallout and fires blossoming on the horizon—they dwindle and dim, going back to the darkness all thoughts and stories come from. A final pulse of ancient light from a dead star—red-blue-green—and there’s nothing left to see and no one left to remember they ever saw it.

Pretend you are the land. Goodbye, you say, slamming a screen door in the wind. Goodbye. Better luck next time.

Text copyright © 2018 by Brooke Bolander

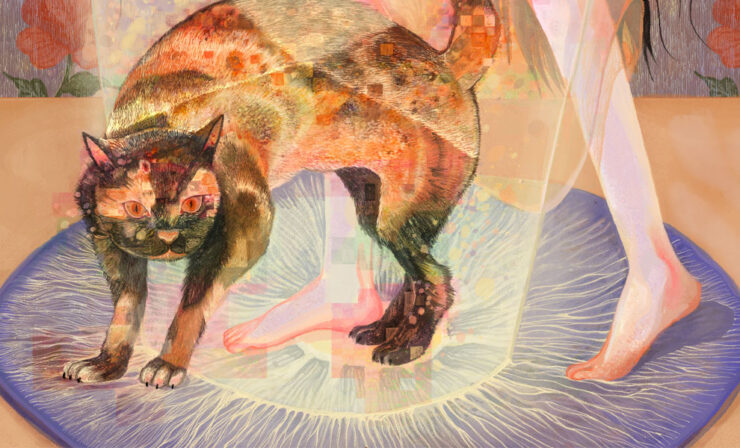

Art copyright © 2018 by Victo Ngai

Buy the Book

No Flight Without the Shatter