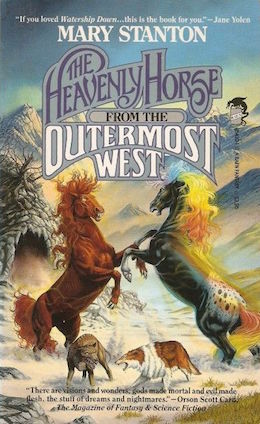

This is a beautiful book, beautifully written, infused with love of horses. It’s a lovely story in the mode of Watership Down and The Wind in the Willows, not to mention the Narnia books. Talking animals, strong moral code, more than a hint of the numinous.

When I first read it I enjoyed it, but it didn’t make the powerful impression on me that it’s made on so many others. It’s iconic, people are always begging me to write about it, and so there was no question that I’d include it in this series. But it never made it to my constant-reread rota.

Now I think I understand why.

I’ve never been the intended audience for talking-animal stories. Even as a small child I wanted real animals. Animals that were animals. Not humans in fur suits, with human concerns and human problems. One of my worst nightmares was to dream that I had a real horse, and to have the horse turn into a stick horse. A symbolic representation. Not-real.

Stanton is a horsewoman. There’s no question about that. She writes from experience. She’s obviously had many horses, and her book is about her feelings for them both generally and in particular. And she writes beautifully.

And yet.

Horse people come in many sizes and shapes and philosophies of life, the universe, and horses. In this book, published in 1988, I recognize so much of the horse world I knew then. Big wooden barns with pastures. A particular mix of breeds—lots of Thoroughbreds, some Quarter Horses and Paints, an Arabian or two, and often an Appaloosa for color (but they had a rep for being stubborn and hard to handle). (I loved them, make no mistake. It wasn’t stubbornness so much as low idiot tolerance. And oh, the spots!)

Horse maintenance was of a particular sort. Everybody shod their horses, broodmares included. Bran mashes were a constant—people believed they were good for the digestion, and a warm mash was essential on cold nights. Colic treatment included (and in most places still includes) walking the horse for hours to try to settle its stomach.

Those things have changed over the years. Shoeing is a different proposition, there’s a whole cult of barefoot trimmers (some of whom are wildly antagonistic to the very idea of shoeing a horse), and broodmares may be kept barefoot unless they require corrective shoeing; even those shoes may be pulled before foaling, for the safety of the foal. Bran is now known to strip nutrition rather than add to it, and may actually damage the horse it’s meant to help. And the pony in the book being forced to walk but being denied water—way to add an impaction to the stress colic she already has.

But for the time, the standard of care was top of the line. If you want to know best practice for horse care in the US in the Eighties, here’s a good example.

Another thing that’s changed over the decades is our understanding of horse color genetics, thanks to the sequencing of the equine genome. Now we can test for a large number of traits including the many variations of color. What that means for the Appaloosa is that we can more reliably predict what colors an individual horse carries in its genes, even if the horse manifests them minimally or not at all. The bare minimum now for an Appaloosa is mottled skin and white eye sclera plus striping of the hooves (though the latter can be iffy if the horse has white leg markings). The horse also, now, has to have at least one registered parent—the registry has tightened up and no longer accepts any horse with the appropriate coloring.

Stanton’s central theme of all Appaloosas losing their color and no longer breeding true wouldn’t be as difficult a situation now as it was before DNA testing. Then again, there’s been an ongoing battle between those who believe all Appaloosas should show visible coloring, and those who believe any horse with Appaloosa parents, whether spotted or solid, should be considered an Appaloosa. So that’s not too far off.

What I don’t quite get from the text is how an Appaloosa can be born with spectacular spotting and turn into a solid buckskin as she matures. I’m not an an expert on the breed, but my observation is that apparently solid foals can color out as they grow, sometimes quite dramatically, but foals born with loud color may “roan out” or turn greyish. (There have been cases of Appaloosas bred to grey horses whose offspring have turned white, but that’s another set of color genetics, unrelated to the Appaloosa color complex.) I haven’t heard of any that turned into vivid solid colors.

And then there’s the few-spot leopard, which is the ultimate breeding cross. It’s a horse who appears to be all or mostly white, but genetically it will always produce color. This only became clear in the 1970s, when a few breeders kept their “white” colts from Appaloosa parents and bred them, and discovered that they were guaranteed color producers regardless of what they were bred to. So complete visual absence of color can conceal genetic treasures. That’s a magic of its own.

One thing I have been told firmly by Appaloosa breeders is never, ever to mix Appaloosa and Paint. It’s not done. So poor Susie couldn’t win even that. Susie is my favorite character; I feel so sad for her because of what happened in the book, but even more so knowing what a real-world breeder would think of the cross.

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

All of this is pretty technical, and I find it interesting, but it doesn’t explain why I bounced off this book as hard as I did. Nor is it entirely that our understanding of feral horse herd dynamics has shifted from the belief that the stallion leads the herd to the observation that the herd member who actually makes the decisions is the lead mare. Mares don’t submit to stallions because they’re the lords of creation; even in breeding, when they seem to be submissive, they’re actually controlling the stallion. Their hormonal status determines his reactions. And if they say no, and they aren’t confined or forced, they can enforce the refusal with a pair of killer heels.

That was where I first began to realize why the book wasn’t working for me. The focus on stallions as the superior gender, and on mares as subject to their will and whim, made me go Nope. Nopenope.

Then there’s Duchess, who doesn’t want to be Lead Mare, and who is pretty much railroaded into it. Horses run a gamut from secure-submissive to secure-dominant, that’s true, and the insecure ranges can be the most dangerous and the most endangered, because they don’t know how to react, or trust those reactions. Insecure-dominant will get aggressive when trying to take over, and insecure-submissive will fight when she should back off. So Duchess is probably insecure-dominant, but around the Dancer she’s totally submissive, which is not the behavior of an alpha mare (and I don’t think she’s elected to the post on an annual basis, either). The only time the alpha will let the stallion order her around is when she’s in standing heat, and even then, she won’t take his crap. He learns really fast to ask nicely and take no for an answer.

So there’s a basic philosophical difference there, which made me want to smack Duchess upside the head. And the Dancer. Oh my. What I wouldn’t give to turn him out with my herd matriarch in her heyday. She’d eat him for breakfast. After she kicked his lights out.

But even more than that, which is a basic difference in attitude toward horse personalities and handling, I found myself pulling back from the human-essentialism of the worldbuilding. The horses are not horses, they’re humans in horse suits. They subscribe to human (modern Western) cultural assumptions, including the dominance of the male. Even physically, they keep showing human traits: a furrow between the eyes when a horse is worried (which is not physically possible; there’s some wrinkling directly above the eyes when a horse is concerned, but the forehead can’t move or wrinkle), or tears when she’s grieving (the only time a horse will shed “tears” is when the tear ducts, which drain through the nostrils, are blocked; that’s a medical issue, not an emotional one).

The fundamental principle of this world is that horses are divided to breeds, and humans create and maintain the breeds, while horses (led by the stallions and the male Equus) fight the eternal battle between good and evil—it’s extremely dualistic; there are no grey areas here. And that’s pretty classic for fantasy. It’s also all about the humans. Human-manufactured breeds. Horses submitting to humans, good and bad. Humans create, horses follow along.

And that was the biggest Nope of all. (Aside from the one about Appaloosa being the oldest breed—no, that’s the Arabian, and the historical basis for the claim about Appaloosas is only a century old, so, nope; however, I cut lots of slack for those who love their breed above all others. That’s a horse person’s prerogative, after all.) The breed thing is such a human hangup, and a very recent one at that. There are strong elements of racism and colonialism in it. It’s not a horse thing at all.

Horses on their own tend to live in family groups. They may gravitate toward horses who look like them, for color or shape or size, and who act like them, culturally and socially. What they do not do is make a cult of specific breeds and lineages, still less build their universe around them.

So that didn’t work for me. I don’t see horses that way, though I’m perfectly willing and able to discuss the pros and cons of the different breeds, and I understand closed studbooks, the why and how. But that’s human taxonomy at work, not horse culture or psychology. Horses don’t care. Their world is built around other priorities, few of which coincide with humans’ unless humans force the issue.

And that’s the biggest thing. Horses are horses. Humans are humans. Their worlds intersect, and it can be a wonderful symbiosis. But like the nightmare of the horses turning into plastic toys, I just can’t live in a world in which horses are simply reflections of human personalities and priorities. It’s the fact they aren’t human that I love most about them.

I got through this reread on the strength of the writing, but the worldbuilding was a big Nope. What it did for me was decide the next book I’ll reread—one that’s been on my personal reread rota since it first came out. It’s another story of a buckskin mare caught up in powerful magic, and it’s one of the most accurate depictions of horse psychology that I’ve ever read.

So, next time: Doranna Durgin, Dun Lady’s Jess. Doranna will show us how to do horses as horses—even when magic has done its utmost to turn them into something else.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.