In 1917, film color processor Technicolor wowed audiences with some of the first moving color images ever projected on screen. But after that initial triumph, things proved a bit wobbly. Their second method, Process 2 Technicolor, which used two strip negatives in red and green to create a color image on screen, had at least solved the problem of needing to find skilled projectionists who could align the images correctly during film performances (a failure of the Process 1 Technicolor), but failed in nearly every other respect. Process 2 created images that were easily scratched, film that could (and often did) fall through projectors, and colors that could be kindly described as “pale,” “somewhat off,” “unrealistic”, or in the words of unkinder critics, “awful.” Undaunted, Technicolor went to work, created an improved Process 3—which projected moving specks onto the screen. Not only did this distort the images; audience members assumed they were looking at insects.

Perhaps understandably, audiences did not rush to see these colored films. So, with the Great Depression still lingering, several film studios considered dropping the costly color process altogether. By 1932, Technicolor faced potential ruin. But the company thought they had a solution: a new three strip color process that could provide vibrant colors that could, in most cases, reproduce the actual colors filmed by the camera. The only problem—a tiny tiny tiny problem—was that the process wasn’t quite ready for film yet. But it might—it might—be ready for cartoons.

They just had to find someone interested in a bit of experimentation.

Luckily for them, Walt Disney was in an experimental mood.

His long time animation partner Ub Iwerks had left the studio in 1930, forcing Walt Disney to hunt down other artists and cartoon directors. He was still working with the shape, form and character of Mickey Mouse, introduced just a couple of years previously, but he wanted something new. Plus, his company had just signed a new distribution deal with United Artists. And he still thought animation could produce something more than it had so far. So when Technicolor agreed to give him an exclusive deal on this new technology in 1932—promising, correctly as it turned out, that live action films would not be able to use it for a couple more years—Walt Disney jumped at the chance, despite the protests of his brother Roy Disney, who did not think that the company could afford to pay for Technicolor.

Roy Disney’s gloomy prognostications were not entirely unfounded. Company records show that although on paper its Silly Symphony cartoons seemed to bring in money, the need to split revenues with United Artists and the initial $50,000 (approximately) cost per cartoon meant that the cartoons usually took more than a year to earn back their costs—and that only if United Artists and movie theaters agreed to run them, instead of choosing a cartoon from Warner Bros or other rivals instead. With the cash flow problem, paying for color was risky at best. Color, countered Walt Disney, might be just enough to persuade their distributor and movie theatres to hang on.

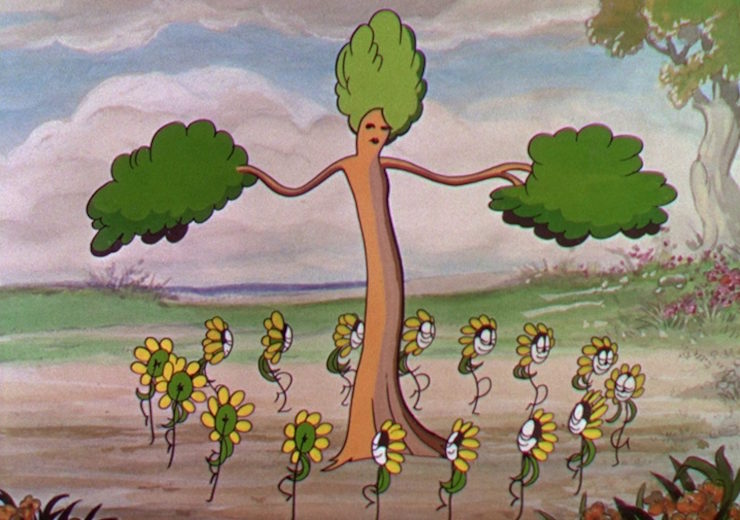

The first Silly Symphony cartoon made with the new process, the 1932 Flowers and Trees, seemed to bolster both points of view: it won an Academy Award for Best Cartoon Short, which helped keep it and Disney in theatres, and it initially lost money. Color, Walt Disney realized, was not going to be enough: he also needed a story. And not just a story based on the common cartoon gags, either. He needed a story with characters. A mouse was doing fairly well for him so far. Why not a story of another animal—say, a pig? Maybe two pigs? Using the rhymes from that old fairy tale? And all in glorious Technicolor? He was excited enough by the idea to force his artists to work, in his own words, “in spite of Christmas.”

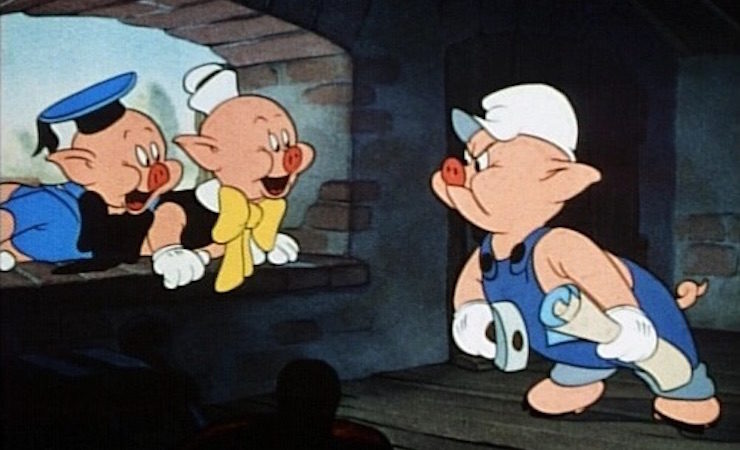

To direct this next short, Walt Disney selected the temperamental Bert Gillett, who had previously directed several Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony shorts. The two almost immediately started fighting. Walt Disney wanted two pigs; Gillett wanted three. Gillett won that point, allowing Walt Disney to win the next “suggestion”—more of a demand. The pigs must not only be cute, but have real personalities—and teach a moral message.

That is, the first two little pigs would not, as in the version recorded by James Orchard Halliwell-Phillips and Joseph Jacobs, receive their building materials by mere chance. Instead, as in the Andrew Lang version, they would deliberately choose weaker building material specifically so that they could build their houses quickly and then goof off. The third little pig wouldn’t just build his house out of bricks: he would pointedly sing about the values of hard work. And since in these pre-“Whistle While You Work,” and “Heigh-Ho” days, no one knew if a song about hard work would be a hit, well. The cartoon could also throw in a song about the Big Bad Wolf.

To compose that song, eventually named “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf,” Disney turned to Frank Churchill. The composer had joined the studio three years previously, churning out compositions for various Mickey Mouse shorts. In the boring version, Campbell agreed to work on this cartoon because he needed the money and liked pigs. In the much more interesting version put out by Disney publicists at the time, Campbell desperately needed to score this cartoon in order to help exorcise a traumatic childhood memory of three little piglets who liked to listen to him play on the harmonica and the big bad wolf who ate one of them. If you are thinking well, that’s a suspiciously convenient story, well, yes, yes it is, and if you are also thinking that it’s rather suspiciously convenient that after no one could confirm that Churchill had ever played the harmonica for pigs of any size the story suddenly vanished from official Disney sources, well, yes, yes, valid point, but you know what? It’s a great story, so let’s just go with it.

A somewhat more plausible publicity story from the time claimed that actress Mary Pickford, then in the process of transitioning from full time acting to full time producing with United Artists, but at Disney to discuss possibly working with the studio on an Alice in Wonderland cartoon, was one of the first outsiders to see the initial designs for the pigs and hear Churchill, story artist Ted Sears and voice actor Pinto Colvig sing “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf.” Publicists claimed that Pickford immediately told Walt Disney that she would never speak to him again if he didn’t finish the cartoon. Unable to say no to Mary Pickford’s charm—or to the fact that United Artists was now his only distributor—Walt Disney agreed. I say “somewhat more plausible” since other records indicate that Walt Disney already loved the pigs and planned to do the short in any case.

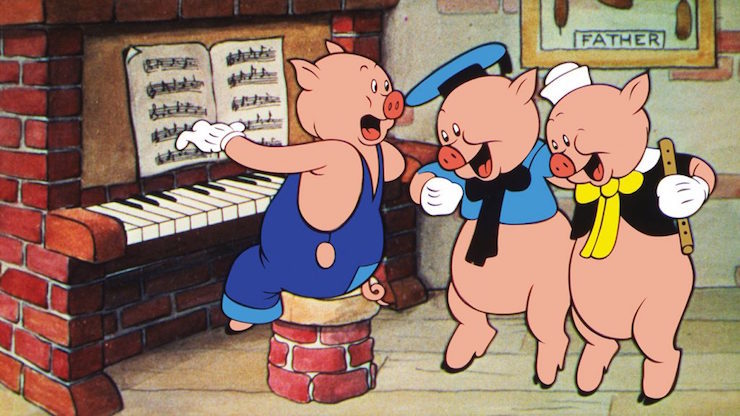

Meanwhile, the animators pushed ahead with Walt Disney’s other demand: creating pigs with personality. In earlier Disney cartoons, the characters had largely been distinguished by size and appearance. Here, the three pigs look virtually identical. Oh, they do wear different hats and clothes—Practical Pig is modest enough to wear overalls, while the other two pigs have decided that life is happier without pants. But otherwise, they are all remarkably similar, with virtually identical faces and body shapes. What would distinguish them was personality. A trick the animators decided to do through facial expressions and movement.

This was probably not quite as revolutionary as animator Chuck Jones would later claim it was—other cartoon animators (and to be fair, previous Disney shorts) had also conveyed personality through movement and faces. But it was still different than most of the cartoons at the time—and it largely works. Granted, I still can’t really tell the difference between Fiddler Pig and Fifer Pig if they aren’t carrying their instruments, but they are obviously different than Practical Pig.

Not that all of the theatre owners and distributors were immediately convinced: at least one complained that they’d gotten more value for their money from previous cartoons which had more than four characters, however cute and different.

The final result was released as a Silly Symphonies short in 1933, presented, as its title page assures us, by no less a personage than the great Mickey Mouse himself. (Mickey Mouse was very busy in the 1930s selling Mickey Mouse merchandise, so taking the time to present a cartoon short was quite a concession.) And in full Technicolor.

The short starts with a pig merrily singing, “I built my house of straw! I built my house of hay! I toot my flute and don’t give a hoot and play around all day!” This would be Fifer Pig, and I think we can all appreciate his total indifference to what people might say about him, and his refusal to wear pants. A second pig follows this with “I built my house of sticks! I built my house of sticks! With a hey diddle diddle I’ll play on my fiddle and dance all kinds of jigs!” It’s all very cheerful.

Alas, the third pig—Practical Pig—turns out to be very grumpy indeed, singing that “I built my house of stone! I built my house of bricks! I have no chance to sing and dance cause work and play don’t mix!” Pig dude, you are literally singing while slapping down mortar between the bricks, so don’t give me this “I have no chance to sing” tuff. Or at least don’t try to sing while making this complaint, because it’s not very convincing. My sympathies are completely with the other two pigs. And not just because they seem a lot more fun.

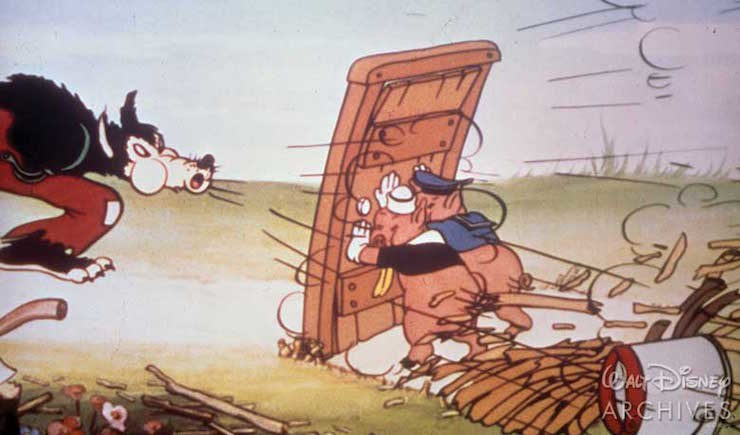

Fifer Pig puts out a nice welcome mat once his house is built, and Fiddler Pig cheerfully dances with him. They try to bring Practical Pig into the fun, but he refuses, telling them that he’ll be safe and they’ll be sorry—leading them to sing “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” When the Big Bad Wolf turns up, the answer, as it turns out, is the two pigs, who aren’t just afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, but terrified. It probably doesn’t help that at this point, the music switches from the jolly chords of “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” to terrifying chords.

Terrified, the pigs rush back to their homes, promising not to let the wolf in “by the hair of my chinny chin chin.” The infuriated wolf responds with the expected “I’ll HUFF and I’ll PUFF and I’LL BLOW YOUR HOUSE IN.”

As someone who had, alas, seen far too many houses that I had carefully crafted out of pillows, stuffed animals, Tinker-Toys and blocks COMPLETELY DESTROYED with a single careless gesture, Small Me could sympathize all too deeply with this and indeed may possibly have reacted with a complete breakdown and a wish that the TV had shown Tigger instead because Tigger was much better than any MEAN WOLF WHO KNOCKED DOWN HOUSES.

The wood house does present the Big Bad Wolf with a slight practical obstacle, but after a moment of thinking, he disguises himself as a sheep—a refugee sheep, at that, calling himself “a poor little sheep, with no place to sleep,” begging to be allowed in. Hmm. The pigs announce that they aren’t fooled, infuriating the Big Bad Wolf again. He blows the wood house down in response.

The pigs flee to the house of Practical Pig, who, I must note, for all his complaints about not having time for music and fun, has taken the time to install a piano. A piano made of brick, granted (in one of the short’s most delightful touches) I’m beginning to believe you are a bit of a hypocrite, Practical Pig.

The Big Bad Wolf follows, desperate to capture a pig.

As part of this, he disguises himself as a Jewish peddler, dripped in every possible anti-Semitic stereotype imaginable.

In 1934.

This scene should not, perhaps, be unexpected. Walt Disney was known to use racist and ethnic slurs in the workplace (along with the constant habit of calling all of his professional women artists “girls,” a habit often picked up and followed by Disney historians) and could hardly be called a shining light in race relations.

In fairness, I should note that one of this cartoon’s direct sequels, The Three Little Wolves, released just a few years later, took a strong anti-Nazi stance. Shortly after this, Walt Disney bought the film rights for Bambi, well aware that the book was an anti-Nazi text banned by the Third Reich, and sunk a considerable amount of money that he and his company could not afford into the film. His company spent much of World War II releasing propaganda and war training cartoons, as well as releasing Victory Through Air Power, a live action/animated propaganda film arguing for the destruction of the Nazi regime.

And in this short, it’s the villain of the piece who chooses to use offensive stereotypes, not the sympathetic protagonists. Also, the entire plan flops.

But this scene has not aged well, to put it mildly.

Anyway. After the costume fails, the Big Bad Wolf attacks. Practical Pig spends quite a bit of this attack playing the piano, like, I’m really starting to view you as a hypocrite now, Practical Pig, but when he hears the Big Bad Wolf trying to enter the house through the ceiling, he takes a large container of turpentine. Why, exactly, does a pig need to keep a large container of turpentine around the house, I ask myself, before realizing that this is precisely the sort of question probably best not asked of Disney cartoon shorts. Practical Pig pours the turpentine into a cauldron conveniently waiting over a fire in the fireplace. The boiling turpentine is the last straw for the wolf, who bolts back out of the chimney and runs off, sobbing. The pigs laugh merrily and return to dancing again, with one last joke from Practical Pig.

So, Practical Pig, you’re generally a complete downer and a hypocrite and play practical jokes on your pig friends. Ugh. No wonder I hate this fairy tale.

It’s an odd mix of brutality and cheerfulness, laced with echoes of the Great Depression, where people found themselves losing homes to forces they could not control. But those echoes are mixed with a strong sense that the cartoon, at least, blames Fifer Pig and Fiddler Pig for their own misfortunes: they chose to dance and sing rather than work, and they chose flimsier building materials. Walt Disney, in a memo, described this as stressing a moral: that those who work the hardest get the reward—a moral that he felt would give the cartoon more depth and feeling.

And I’m almost willing to buy the ethical lesson here, despite that tinge of victim blaming, and lack of sympathy for refugees—because, after all, Practical Pig does work quite hard, and deserves some reward, and does ungrudgingly provide a refuge for the other two pigs, saving their lives. At the same time, however, I can’t help noticing that in addition to being a downer and a hypocrite, Practical Pig also keeps suspiciously large amounts of turpentine around and has a rather alarming portrait on his wall of a long string of sausages labelled “Father.” Okay, Practical Pig. I’m now officially worried about you—and not completely convinced that you deserve your happy ending, any more than Fifer Pig and Fiddler Pig deserved to lose their homes. The world needs music and dancing as much as it needs bricks.

Audiences did not share my worries. They loved the pigs. The cartoon became Disney’s hands down most financially successful cartoon short, leaving even the Mickey Mouse shorts far behind; adjusted for inflation, it holds this record today. “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” was even more popular, taken up first as a theme song for the Great Depression, and then by U.S. troops heading off to Nazi Germany. Critics and industry insiders were impressed as well. The Three Little Pigs won an Academy Award in 1934 for Best Animated Short in recognition of its popularity and animation breakthroughs.

It was even popular enough to be referenced by Clark Gable during It Happened One Night (1934). That film, in turn, was supposedly one of the inspirations for Bugs Bunny, who later starred in The Windblown Hare, one of the three WB cartoon shorts also based on this folktale. (What can I say? Hollywood, then and now, has not always been a well of original thinking.)

The Three Little Pigs had a substantial legacy on Disney as well. United Artists immediately demanded more pigs, and although Walt Disney wanted to try new things, he could not risk alienating his distributor, and reluctantly released three more shorts: The Big Bad Wolf (also featuring Little Red Riding Hood) in 1934; Three Little Wolves in 1936; and The Practical Pig (easily the most brutal of the lot) in 1939. None were particularly successful, but all kept income coming into the studio during financial lean times.

Meanwhile, the income from The Three Little Pigs convinced Walt Disney that audiences would flock to see animated stories, not just cartoon gags—and helped finance Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the company’s first full length animated film. In later years Walt Disney liked to say that the company had all been started with a mouse. It’s equally possible to argue that the company really got its success from the pigs.

But the hands down most influential legacy of the short was on Technicolor and film in general. The Three Little Pigs was often more popular than the feature films that followed it, convincing studios that even though the previous color processes had not drawn in audiences, the new three strip color process, however expensive, would. Distributors, indeed, began demanding Technicolor films, ushering in a lushly colorful film era that was only temporarily halted by the need to cut expenses during World War II. And it all started with pigs.

If you’ve missed the short, it’s currently available on an edited, authorized version on The Disney Animation Collection, Volume 2: Three Little Pigs, and, depending upon Disney’s mood, on Netflix streaming, as well as a completely unauthorized YouTube version that may not still be there by the time you read this. Purists should note that the official Disney releases have edited out the Jewish peddler scene, though it can still be viewed on the YouTube version.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.