Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

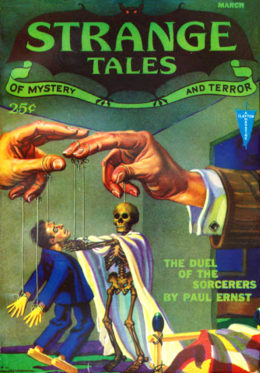

Today we’re reading H. P. Lovecraft and Henry Whitehead’s “The Trap,” written in 1931 and first published in the March 1932 issue of Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror. Spoilers ahead.

“And in some outrageous fashion Robert Grandison had passed out of our ken into the glass and was there immured, waiting for release.”

Summary

Narrator Canevin has traveled far afield, most recently in the Virgin Islands, where in the outbuilding of an abandoned estate-house he discovered a mirror dim with age but graceful of frame. Sojourning in Connecticut as tutor in a friend’s school, he finally has an opportunity to break the mirror out of storage and display it in his living room.

The smaller mirror in his bedroom happens to face the antique mirror down the separating hallway. Brushing his hair one December morning, Canevin thinks he sees motion in the larger glass but dismisses the notion. Heat is off in the rest of the school, so he holds class in his living room. One boy, Robert Grandison, remains after the others. He sits near the old mirror, gazing at it with odd fascination. When asked what attracts his attention, Robert say it seems like the “corrugations” in the glass all lead to the same point in the lower left corner. He points out the place, but when he touches it, he pulls back with a muttered “ouch”—foolish, he knows, but it felt like the glass was trying to suck him in. Actually, from close up, Robert can’t even be sure of the convergence spot.

No, Canevin later confirms. One can only spot the convergence phenomenon from certain angles. He determines to investigate the mystery further, with Robert’s help, but when he looks for the boy at evening assembly, he’s gone missing.

He stays missing, having disappeared from school, neighborhood, town. Search parties find no trace. His parents come and depart a few days later, grieving. The boys and most teachers depart for the Christmas holiday subdued. Canevin remains, thinking much about the vanished Robert. A conviction grows on him that the boy is still alive and trying desperately to communicate. A crazy notion? Maybe not—in the West Indies Canevin has encountered the unexplained, and learned to grant tentative existence to such things as telepathic forces.

Sure enough, sleep brings him vivid dreams of Robert Grandison transformed to a boy with greenish dark-blue skin, struggling to speak across an invisible wall. Laws of perspective seem reversed. When Robert approaches, he grows smaller. When he retreats, he grows larger. Over the next several nights, the dream-communications continue, and Canevin is able to piece together Robert’s story and situation. The afternoon of his disappearance, Robert went alone to Canevin’s rooms, and yielded to the compulsion to press his hand to the mirror’s convergence point. Instantly, agonizingly, it pulled him in, for the mirror was “more than a mirror—it was a gate; a trap.”

In this “fourth dimensional” recess, all things were reversed: perspective laws, colorings, left/right body parts (symmetrical pairs and nonsymmetrical organs alike, apparently.) The recess was not a world unto itself, with its own lands and creatures. It seemed rather a gray void into which were projected certain “magic lantern” scenes representing places the mirror had fronted for long periods, strung loosely together into a panoramic background for the actors in a very long drama.

Because Robert wasn’t alone within the mirror-trap. An antique-garbed company has long lived, or at least existed, there. From the fat middle-aged gentleman who speaks English with a Scandinavian accent to the beautiful blonde (now blue-black) haired girl, from the two mute black (now white) men to the toddler, they have all been brought there by “a lean elderly Dane of extremely distinctive aspect and a kind of half-malign intellectuality of countenance.”

The malignly intellectual Dane is Axel Holm, born in the early 1600s, who rose to prominence as the first glazier in Europe and was particularly noted for his mirrors. His ambitions went much beyond glasswork, however; nothing less than immortality was his goal. When a very ancient piece of whorled glass with cryptic properties came into this possession, he fused it into a magnificent mirror that would become his passage into a dimension beyond dissolution and decay.

A one-way passage, however, thus a prison however well Holm has stocked it with slaves and books and writing paper, later with companions lured into the mirror by telepathic trickery (like Robert, who may rather enjoy conversing with philosophers two centuries older than himself for a week or so but doesn’t look forward to an eternity of the same.)

Canevin, armed with Robert’s inside intelligence, devises a plan to free him. As best he can, he traces the outline of Holm’s whorled relic and cuts it out of his mirror. A powerful smell of dust blasts from the aperture, and he passes out.

He comes to with Robert Grandison standing over him. Holm and all the others are gone, faded into dust, hence that smell that overcame Canevin. Canevin recovered, Robert collapses for a while. Then the two connive at an “explicable” story to restore Robert to life and school: they’ll say he was abducted by young men on the afternoon of his disappearance as a joke, got hit by a car escaping, and woke ten days later being nursed by the kind people who hit him. Or something like that—at least it’s more believable than the truth!

Later Canevin does more research on Axel Holm and deduces that his small oval mirror must have been the mythical treasure known as “Loki’s Glass.” Loki the Trickster indeed! He also realizes that the once right-handed Robert is now left-handed, checks and hears Robert’s heart beating within the right side of his chest. So what they two experienced was no delusion. One mercy is that at least Robert’s coloration reversal reversed, so he didn’t return to our world looking like Mystique. Or maybe more Nightcrawler.

Oh, and Canevin still has Loki’s Glass, as a paperweight. When people assume it’s a bit of Sandwich glass, he does not disillusion them.

What’s Cyclopean: Not much adjectival excitement this week. The narrator commends 15-year-old Robert’s “unusual vocabulary” when the boy says something is “a most peculiar sensation.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Living in the West Indies obviously makes you far more willing to believe in the supernatural. What it doesn’t do is make you think of an evil wizard’s “dependable slaves” as real people.

Mythos Making: The mirror connects with “spatial recesses not meant for the denizens of our visible universe, and realizable only in terms of the most intricate non-Euclidean mathematics.”

Libronomicon: The narrator makes allusion to Through the Looking Glass, the tale of a rather-more-pleasant world accessible through a mirror.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Narrator knows that if he shares his suspicions about the mirror with his fellow teachers, they’ll question his mental state. Has no one else been to the West Indies?

Anne’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Coming out of the day-job week from so low a circle of Hell that I am seriously considering taking a PR job at the Trump White House, I have very little energy for comments this week. But you are fortunate. Because if I did have any energy, I would probably only use it for such Evil Purposes as writing something like this:

From the shifting aqueous shadows floats a web-digited hand. It floats toward an ornately framed mirror in which those shifting shadows dance fiendish sarabandes of fiendish glee, almost—almost—but not almost enough—obscuring the convergence of whorls on a certain point in the lower left corner of aforesaid mirror.

Algae films the glass of the mirror, but he who approaches can still see the goggle of his eyes and gape of his mouth, more a-goggle and a-gape than usual. I know what you are, he thinks.

But

Oh

Why

Not

The webbed digits descend on the convergence point. The suction takes hold at once. He is slurped in with only time to burble “IT’S—”

A TRAP!

Okay, so I gave in to Evil and wrote it anyway. I can only add that if Axel Holm had lived just a wee bit later, he could have corresponded with Joseph Curwen and Friends and found out a much better method for immortality. At least a far less tedious one!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Mirrors are inherently creepy. I say this based on the unassailable authority of having refused to look at them after dark for most of my childhood. It’s a piece of glass that appears to exactly match the familiar world around you… almost. And yet there are always flaws in the reflection, especially in an old mirror where the glass, or the reflective surface behind it, is distorted. Look too closely, and you might find greater discrepancies. And you don’t want to do that. After all, you don’t really believe that it’s just an innocent reflection, but you wouldn’t want proof. Because if you knew for sure, that thing trying to pass itself off as your reflection might come out. Or maybe pull you in…

Whitehead’s trap is the latter kind of creepy mirror, a hungry thing that wants to claim bits of reality for itself. Some of that is due to evil wizard/glassblower Holm, actively seeking company in his tedious immortality. But the weird connection to places the mirror has reflected, its ability to absorb some part of them over time, appears to be due to Loki’s Glass. I can’t help suspecting that it has its own malign intelligence, and puts up with humans wandering among its thoughts and memories (Hugins and Munins?) for purposes of its own. But then, I’ve committed fanfic from the POV of the One Ring, so I would.

Speaking of tedious immortality—seriously, Axel, you had vast cosmic powers, and this itty-bitty living space was the best idea you could come up with? Not all routes to immortality are created equal. A truly rational evil wizard would compare their options before settling on “stuck in mirror, not able to touch anything, all your guests hate you.” It’s possible to do worse: getting stuck in a frozen mummy seems even more maddening. But you could preserve your undying body in the real world—maybe a 6 on the awful/awesome scale, since dependence on air conditioning is balanced by continued enjoyment of physical luxury and the ability to send out for new books. You could steal someone else’s perfectly good body—that’s an 8 or a 9, depending on how well you like the body and how hard it is to find a new one.

You have options, is all I’m saying.

Unlike Holm’s poor co-denizens, dragged along for company/servitude and not permitted so much as a piece of luggage, let alone the library he managed for himself. In particular, the narrator doesn’t spare nearly enough sympathy for Evil Wizard’s unnamed slaves, who were already in a horrible spot before being made beta testers for travel to Mirrorland. “What his sensations must have been upon beholding this first concrete demonstration of his theories, only imagination can conceive.” I would not, personally, trust anyone who, considering this situation, instinctively imagines Holm’s sensations before imagining those of his subjects. Lovecraft described Whitehead as “an utter stranger to bigotry or priggishness of any sort,” but he may not have been the best judge.

It is interesting to read a Lovecraft collaboration with so few of his fingerprints. Whitehead had a long and successful career in weird fiction on his own, only two of which were in concert with his friend and correspondent. Some of the infodumps feel a bit Lovecraft-ish, but the adjectives verge on pedestrian, and the narrator shares Whitehead’s comfort with mentoring young men, as well as his time in the Virgin Islands. Plus, there’s occasionally actual dialogue. I’m curious to read more of Whitehead’s solo work for comparison.

Closing thought: awfully convenient for Robert that his coloration switches back when he comes home, even if nothing else does. Trying to explain that with a car accident would’ve been about as believable as Spock’s mechanical rice picker.

Next week, despite the illusory nature of time, is our 200th post! We’ll be watching Howard Lovecraft and the Frozen Kingdom; come find out along with us how this film managed to earn almost four stars on Rotten Tomatoes!

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.