In stark contrast to the long, intricate tales penned by other literary fairy tale writers, in particular those practicing their arts in French salons, most of the fairy tales collected and published by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are quite short—in many cases, easily squeezed into just one or two pages, or even just a few paragraphs. One major exception: “The Juniper Tree,” one of the longest tales in the original 1812 Children’s and Household Tales, which also happens to be one of the most horrifying tales in the original collection.

In their notes, the Grimms gave full credit to painter Philip Otto Runge (1777-1810) for providing them with the tale. Although some scholars have argued that the story is an original tale penned by the Grimms, who were inspired by Runge’s paintings, the only other confirmed original tale by the Grimms, “Snow White and Rose Red,” did not appear until the 1833 edition. This suggests that Runge may well have penned “The Juniper Tree,” especially since unlike the other tales in the original 1812 edition, it has no clear oral or written source. Or perhaps Runge did simply write down an otherwise lost oral tale.

Runge, born into a large, prosperous middle-class family, spent much of his childhood sick, which allowed him to both miss school and indulge in various arts and crafts. Seeing his talent, an older brother paid for him to take art lessons at the Copenhagen Academy. Unfortunately, Runge developed tuberculosis only a few years later, cutting short what had been an exceptionally promising career.

Before his death, Runge painted a number of portraits, as well as more ambitious paintings intended to be displayed with music. Since this was well before the age of recordings, those paintings presented some logistical problems, but the effort signified Runge’s desire to fuse together various art forms—which may in turn perhaps explain what he was attempting to achieve in “The Juniper Tree,” a tale laced with repetitive poetry.

The story opens with a familiar fairy tale motif: a wealthy woman longing for a child. One snowy day, she steps outside to cut an apple beneath a juniper tree. I have no idea why she doesn’t stay in a nice warm room to cut the apple. Sometimes rich people can be strange. Moving on. She cuts her finger, letting a few drops of blood fall beneath the juniper tree, and wishes for a child red as blood and white as snow—consciously or unconsciously echoing the mother of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” She feels considerably better after cutting herself and wishing for this child—the first of many disturbing elements in the tale.

Nine month later, she has a child, and dies.

As requested, her husband buries her under the juniper tree.

Eventually, he remarries.

He and his new wife have a daughter—Marlinchen, or, in a recent translation by Jack Zipes, Marlene. That’s shorter to type, so we’ll stick with Marlene. His new wife knows that her stepson will inherit everything. Her daughter, nothing. It’s the evil stepmother motif, with a clear cut financial motive. She begins physically abusing the boy.

And one morning, after her daughter asks for an apple, which this family, for whatever reason, keeps in heavy chests, the mother has a terrible thought. She tells her daughter that she must wait until her brother returns from school. When he does, she coaxes the boy towards the chest, and murders him with its lid, decapitating the poor kid within seconds.

THIS IS NOT THE MOST DEPRESSING OR GROSS PART OF THE STORY, JUST SO YOU KNOW.

Like many murderers, her immediate concern is to not get caught, so, she props up the body and ties the head to it with a nice handkerchief like that is not really what those things are for and then puts an apple in the dead kid’s hand and then tells her little daughter to go ask the kid for the apple and if he says no, hit him. Marlene does, knocking the boy’s head off, proving that handkerchiefs, however useful in other situations, are not really the most reliable way to secure heads to necks after decapitation. Consider this your Useful Information for the Day.

While I’m being useful, SIDENOTE: I must warn my younger readers not to try to reenact this scene with Barbie, Ken and Skipper Growing Up dolls. Grown-ups will not be in the least appreciative and you may not get a replacement Barbie doll.

Moving on.

Marlene, naturally, is more than a bit freaked out. Her mother then manages to worsen the situation by saying that they absolutely must not let anyone know that Marlene has killed her own brother (!) and thus, the best thing to do is to turn the boy into stew. She then feeds it to the father, who finds it very tasty, as Marlene watches, sobbing.

This bit with the stew, incidentally, was edited out of most English editions of the tale, much to the irritation of several scholars, perhaps most notably J.R.R. Tolkien, who remarked:

Without the stew and the bones—which children are now too often spared in mollified versions of Grimm—that vision would largely have been lost. I do not think I was harmed by the horror in the fairy tale setting, out of whatever dark beliefs and practices it may have come.

Granted, this is from the same man who later conjured up an image of a giant hungry spider blocking the entrance to a monstrous land of fire and despair, so, I dunno, maybe you were harmed just a tad, Tolkien. Or maybe not. But the belief that he was not harmed by reading about kiddie soup formed a central plank of a longer essay urging us not just to stop relegating fairy tales to children, but also to stop shielding children from fairy tales. They’ll live. And they probably won’t try to turn their siblings into soup. Probably.

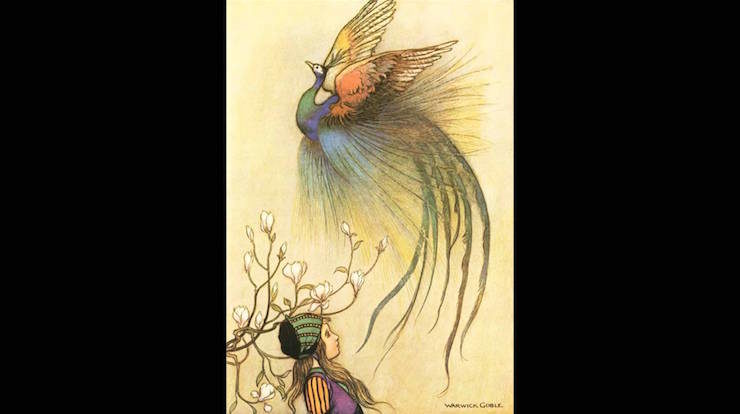

Back in the story, Marlene carefully gathers up her brother’s bones and places them beneath the juniper tree. The tree reacts the way many of us would, when offered human bones: it moves. It then does something most of us can’t do: it releases smoke, and then a white bird. Marlene sees the bird and cheers up instantly, heading back inside to eat.

Which is kinda a mistake on her part, since it means missing one of the great ghost outings of all time, as the bird decides to fly through the town, pausing at various places to sing a cheery little song about his murder, ending with the line “What a lovely bird I am!” Incredibly enough, the goldsmith, shoemaker and the various workers at the mill don’t respond to the line, “My father, he ate me,” with a “What the hell?” but rather with a “Can you sing that again?” On the other hand, plenty of people like rewatching horror movies and TV shows, so, maybe the story is onto something here. The bird has figured out how to monetize this: offer something for free the first time around, and then demand payment for a repeat. As a result, he gains a gold chain, a pair of red shoes, and a millstone.

And then the bird returns home.

The final scene could almost be lifted out of a modern horror movie, particularly if it’s read out loud by someone very very good at doing ghost voices. Even if not read out loud, the image of a bird singing happily about his sister gathering his bones as he tosses red shoes at her is… something.

But this story gains its power, I think, not so much from the repetitive poetry, or the bird’s revenge, or even the image of a father eagerly swallowing stew formed from his son’s legs, or his daughter carefully gathering up his son’s bones from the floor, but for its focus on an all too real horror: child abuse, and how that abuse can be both physical and mental. It’s notable, I think, that this story starts with emotional and verbal abuse before ramping up to child murder and cannibalism, and that it emphatically places the murder of children on the same level as cannibalism. These things happen, the story tells us, and the only fantastic part is what happens afterwards, when Marlene gathers her brother’s bones and soaks them with her tears.

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

It holds another horror as well: the people in the town are more than willing to listen to the singing of the bird, and more than willing to pay the bird for the performance, but not willing to investigate what is a pretty terrible crime. Instead, they just ask to hear the song again, finding it beautiful.

The story also touches on something else that almost certainly came from Runge’s personal experience, and direct observations from the Grimms: the problems with inheritance laws in large families. As a middle child, Runge had no hope of inheriting much from his prosperous parents. His training was paid for by an older brother, not a parent. The Grimms had nothing to inherit from their father, who died young, so this was less of a concern for them—but they presumably witnessed multiple cases of older sons inheriting, leaving younger siblings to scramble, the situation that the mother in this story fears for her daughter, Marlene.

In the end, it can be assumed that this particular son will take very good care of this particular younger sister, even if the father marries a third time. And he might: he’s well to do (and now has an added gold chain, courtesy of a terrifying singing bird), single again, and clearly not overly cautious or discriminating in his choices of women. It’s quite possible that Marlene and her brother might find themselves with more half siblings turned potential rivals—or at least seen as such by their new stepparent—allowing the cycle to start again.

Though even if the father embraces chastity after this, I still can’t help thinking that both Marlene and her brother will find themselves frozen from time to time, especially at the sight of bones, and that neither one of them will be able to eat apples without a shiver of memory—if they can eat apples at all. Because for all its happy ending, and promise of healing and recovery, and for its promise that yes, child abuse can be avenged, “The Juniper Tree” offers more horror, and terror, than hope. But it also offers something else to survivors of childhood abuse: a reminder that they are not alone.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.