A futuristic murder mystery about detective partners—a human and an enhanced chimpanzee—who are investigating why a woman murdered an apparently random stranger on the subway.

“Doesn’t look like a killer, does she,” Huxley remarks.

Cu shrugs a hairy shoulder. To her, all humans look like killers. What her partner means is that the woman in the interrogation room does not look physically imposing. She is small and skinny and wearing a pale pink dress with a mood-display floral pattern; currently the buds are all sealed up tight, reflecting her arms wrapped around her knees and her chin tucked to her chest.

The interrogation room has made a similar read of her mood, responding by projecting a soothing beach front with flour-white sand and blue-green waves. The woman doesn’t seem to be aware of her holographic surroundings. Her eyes, small and dark in puddles of running makeup, stare off into space. Every few seconds her left hand reaches up to her ear, where a wireless graft winks inactive red. Apart from that, she’s motionless.

Cu holds her tablet steady and jabs the playback icon enlarged for her chimpanzee fingers. She crinkles her eyes to watch as the woman from the interrogation room, Elody Polle, bounces through the subway station with her dress in full bloom. With a bland smile on her face, she walks up behind a balding man, pulls the gun from her bag, pulls the trigger, remembers the safety is on, takes it off and pulls the trigger again.

“So calm,” Huxley says, tearing open a bag from the vending unit. “She was like that the whole time, apparently, up until they stuck her in interrogation. Then she lost her shit a bit.” He grins and shovels baked seaweed into his mouth. Huxley is almost always grinning.

Cu flicks to the footage from interrogation: Elody Polle sobbing, pounding her fists against the locked door. She looks over at her partner and taps her ear, signs Faraday shield?

“Yeah,” Huxley says, letting the bag fall to his lap to sign back. “No receiving or transmitting from interrogation. As soon as she lost contact with that little graft, she panicked. The police ECM should have shut it down as soon as she was in custody. Guess it slipped past somehow.”

Acting under instructions, Cu suggests.

Huxley see-saws his open hands. “Could be. She’s got no obvious connection to the victim. We’ll need to have a look at the thing.”

Cu scrolls through the perpetrator’s file. Twenty years’ worth of information strained from social media feeds and the odd government application has been condensed to a brief. Elody Polle, born in Toronto, raised in Seattle, rode a scholarship to Princeton to study ethnomusicology before dropping out in ’42, estranged from most friends and family for over a year despite having moved back to a one-room flat in North Seattle. No priors. No history of violence. No record of antisocial behavior.

Cu checks the live feed from the interrogation room. Heart-rate down, she signs, tucking the tablet under her armpit. Time to talk.

Huxley looks down into the chip bag. “These are terrible.” He shoves one last handful into his mouth, crumbs snagging in his wiry red beard, then seals the bag and puts it neatly in his jacket pocket. He licks the salt off his palms on the way to the interrogation room.

The precinct is near empty, but there are still curious faces peering from the cubicles as they pass. Cu doesn’t come to the precinct often. Huxley had to beg her to put in an appearance. She prefers working from her apartment, where everything is the right size and shape and there are no curious faces.

The outside of the interrogation room looks far less pleasant than the interior: it’s a concrete cube with a thick steel door that seals shut once they pass through it.

Cu squats down a respectable distance away from the perpetrator, haunches sinking through the holographic sand onto padded floor. Huxley pulls up a seat right beside her.

“Good evening, Ms. Polle,” he says. “My name’s Al. You doing okay in here?”

Elody Polle sucks in a trembling breath, and says nothing.

“This is my partner, Cu,” Huxley continues. Elody’s eyes travel over to her, but don’t register even a hint of surprise. “We need to get a better idea of what happened earlier, and why. Can you help us with that?”

Elody says nothing.

Cu takes a closer look at the earpiece. The graft is puffy and slightly inflamed. A DIY job, maybe. Ask her about the piece, she signs. We would hate to remove it.

“Cu’s curious about that wireless,” Huxley says. “So am I. In the subway footage, the way you’re bobbing your head, it almost looks like someone was talking you through the whole thing. Want to tell us about that?”

A flicker crosses Elody’s face. Progress.

“Because if you don’t, we’ll have to remove the earpiece and have a look for ourselves,” Huxley says. “As much as we’d hate to ruin that lovely graft job.”

Elody claps her hand protectively over her ear. “Don’t you fucking dare!” She tries to shout the words, but her voice is hoarse, flaked away to almost a whisper. As if she hasn’t spoken aloud in months.

Cu pulls up the speech synth on her tablet and taps out eight laborious letters, one question mark.

“Echogirl?” the electronic voice blurts.

Elody’s eyes winch wide. As she looks over at Cu, her cheek gives a nervous twitch.

Huxley’s furry red brows knit together. He signs, what the fuck is that.

Echogirl, echoboy, Cu signs. Use an earpiece, eyecam. Rent themselves out to someone who says where to go, what to do, what to say.

Thought that was. Huxley’s hands falter. “A kink, sort of thing,” he says aloud, and Elody’s face flushes angry red.

“It’s a lifestyle,” she says. “She told me you wouldn’t understand. Nobody does.”

“Is she going to come get you out of this mess?” Huxley demands.

“Of course she is.” Elody purses her lips, turns away.

Huxley turns to Cu. Take the earpiece? he signs. Or what?

Cu scratches under her ribs, watching a tremor move through Elody’s hunched shoulders. Offer turn off the Faraday, she signs.

Huxley nods, then turns back to address Elody. “I bet she won’t,” he says. “I bet you a twenty, and half a bag of chips. Well.” He pats his coat pocket and the bag rustles. “A third. Yeah, in fact, I bet the last thing she’s ever going to say to you was pull the trigger. Should we turn off the shielding and see?”

Elody turns back, eyes shiny with tears. “Yes,” she whispers. “Please, I need to hear her voice, I need…” Her tone is eager, but Cu can see uncertainty in the tightening of her eyelids, the bulge of her lower lip.

Huxley makes a show of rapping on the door, telling them to turn off the Faraday. There’s a sudden subtraction from the white noise as the generator cuts out, then Huxley’s phone starts vibrating his pocket with updates.

Cu keeps her attention on Elody, who has her face upturned now as if waiting to feel sunshine: eyes shut, eyelashes trembling, breath sucked in.

“Baby? Are you there?” she whispers. “Are you there? Are you there?”

Her bland smile is back in place. Seconds tick by. Then doubt moves in a slow ripple across her features. Her smile trembles, smooths out, trembles again. Finally, her face crumples and a huge sob shudders through her body.

Cu taps five letters into the speech synth. “Sorry,” her tablet bleats. Then she turns to Huxley and signs get the piece. He nods, thumbs the order into his phone. When they exit the interrogation room, two officers are already waiting to come in: one carrying a black kit, the other snapping on surgical gloves.

Cu hears Elody start to wail just before the door clanks shut behind them.

“That…echogirl thing.” Huxley’s hands piece the new sign together. You’ve thought about it, eh?

I’ve done it, she signs back. Good to walk in the city without crowds. Just never asked them to shoot someone.

As soon as she’s back in the apartment, Cu dials up the heat and humidity and takes off her clothes. Some days she doesn’t mind wearing the carefully tailored black suit. Today she hates it. She leaves it pooled on the floor and takes a flying leap at her climbing wall; the shifting handholds don’t shift fast enough and she’s up to the rafters in an instant.

Cu was specific with the contractors about leaving the rafters exposed. She’s added to them since, welding in more polymer cables and struts of wood, a criss-crossed webbing that spans the vaulted ceiling like a canopy. The design consultant, an excitable architect from Estonia, suggested artificial trees sprouting hydroponic moss. But Cu has no use for green things. She grew up in dull gray and antiseptic white.

Clambering into her hammock, Cu looks out the wide one-way window, watching the sun sink into Puget Sound. She enjoys looking at water so long as it’s far away. The view is expensive, but Cu can afford it. She was awarded damages after the personhood trial, enough for a lifetime of this particular view, enough so she can stay in here forever without needing to earn a penny more. She would go insane, though.

So she works the cases. She was always drawn to crime as a dissection of human nature, the breakdown of motive and consequence. A window into the subtle differences between her mind and all the minds around her. When she first applied for police training with the SPD, it was viewed as a joke. Her acceptance, a publicity grab.

But in the years since, they’ve realized she sees things most humans miss. Cu pulls on her custom-fitted smartgloves, one for each hand and a third for her left foot, and leans back in the hammock. The ceiling screen above her hums to life. New details flit onto the case file, and there’s a message waiting from Huxley.

Thanks for coming down in person, the bossman’s been up my ass about it. Wanted fresh footage for the promo kit. Hoping they shop out my beer belly.

Cu swipes it aside and reaches for the tech report on the perp’s earpiece. The text flows across the ceiling in slow waves, a motion programmed to help her eyes track it easier. There was no salvageable audio data. Not from Elody and not from whoever was speaking to her. But there is usage data to confirm that Elody was receiving a call from a masked address at the time of the murder.

By the look of it, Elody had been in that same call for just under six months. Cu moves backward through the log, perplexed. There are small gaps, a few hours here and there, but Elody had been in near 24/7 communication with her client for half a year preceding the murder.

Cu tries to imagine it: a voice whispering in her ear when she woke up, telling her what to do, where to go, what to say, and whispering still as she fell asleep. All of it culminating in Elody Polle walking up behind a man in a subway and executing him in broad daylight.

She flips the case file over to see the victim’s profile again. The balding man was named Nelson J. Huang. A biolab businessman, San Antonio–based, in the city for a conference. It’s possible that someone with a personal vendetta knew he would be in Seattle and began laying the groundwork for his murder at the hands of Elody Polle six months in advance.

It’s more likely that he was selected at random from the crowd, so someone half the world away could experience homicide vicariously before abandoning her mentally-unstable echogirl.

A call from Huxley jangles across the screen. She pops it open. Her partner is walking down a neon-lit street, sooty brick wall behind his head. “Hey, Cu,” he says. “Busy?”

Sometimes he asks it to needle her; this time it’s because he’s distracted. Cu shakes her head.

“The techies are still trying to track that address, but I doubt they’ll have much luck,” he says, stopping at a light. “Whoever it is, they did a good job wiping up afterwards. No audio data.” He looks around and starts walking again, bristly red beard bobbing up and down. “But before this client, she had another one for around two months. Figured I would swing past and see him on my way home. Well. Sort of see him.”

Where? Cu signs.

“A party,” Huxley says, his grin notching a little wider. “So, if you’re not busy, you should come. Said you’ve done this before, right?”

Cu watches as he digs an earbud out of his pocket and taps it active, worms it into place. Then the slip-in eyecam: he rolls his eye around afterward and blinks away a few tears. The perspective jumps from his phone camera to his eyecam and all of a sudden she’s seeing what he sees. A bright red door in a grimy brick facade, no holos or even a physical sign above it. Through the earbud, she hears the dim pulse of music, synthesized drums.

I hate parties, Cu signs.

“Good thing it’s also work,” Huxley says.

Cu settles back in her hammock and watches his pale hand push open the door.

The interior is dim-lit, noisy, full of bodies. People are dancing—Cu can enjoy rhythm, but the hard pulse of the drums unnerves some deep part of her, sounding too angry, too much like a warning. People are drinking—Cu tried it once, but the warm dizziness reminded her of the sedatives they used to give her. When she related as much to Huxley, he told her she wasn’t even legal yet, technically, and that she would like it when she was older.

It’s a typical party, apart from the fact that every single person in the room is wearing an earpiece.

“Echo, echo, echo,” Huxley mutters. “The client’s name is Daudi. Judging by rental history, he’s probably a blonde.” He takes out his phone and Cu watches his thumb move, sending her a file. It pops up in the corner of her screen, unfurling a list of Daudi’s rental preferences. She searches the crowd for possible matches as Huxley moves into the room. There’s a woman passing out small plastic tubes; Huxley takes one. Cu inspects it as he juggles it in his palm.

“Smooths things out,” the woman says, then something inaudible after.

“Fuck’s this, Cu?” Huxley asks.

Cu signs her response in the air above her hammock; the smartgloves turn it into text in the corner of Huxley’s eye. Some echoes use a drug to weaken willpower. She has to type out the name. Chempliance.

“Elody’s tox screen was clean, right?” Huxley says, twirling the tube in his fingers.

Wouldn’t matter anyway, she signs. Drug is an MDMA derivative. Suggestibility is all placebo effect.

Huxley’s hand disappears, either dropping the tube or pocketing it. Cu doesn’t bother to ask. She keeps scanning as he circulates through the party, looking for someone who meets Daudi’s profile. Huxley mostly keeps his gaze moving, but occasionally sticks on a particularly symmetrical face or muscular body.

They spot two drinkers huddled together at a glass-topped table, skin lit red by the Smirnoff advertisement playing under their elbows, one reaching to stroke the other’s thigh. The man is dressed in an artfully gashed suit and his eyes are glazed with chempliance. The woman has a dress that flickers transparent to the rhythm of an accelerating heartbeat. Both of them move slowly, as if they’re underwater. Something about the woman’s face is familiar.

Cu pulls up the file, checks Daudi’s preferences against the pair. That’s him, she signs. Bar.

Huxley’s vision bobs as he nods his head. He walks over and inserts himself between the couple. “My turn to talk. Get lost, fucko.”

When the man doesn’t move fast enough, Huxley seizes his collar and shoves him off the stool. He stumbles, catches himself. He sways on his feet, listening to the instructions in his ear, looking confused.

“You got some nerve, barging in here like that,” he says, with the intonation a little off.

“This isn’t playtime,” Huxley says. “It’s police business. Walk.”

The man spins on his heel and shuffles backward toward the dance floor, feet slip-sliding.

Huxley shakes his head. “These fucking people, Cu,” he mutters. “That’s a moonwalk, if you were wondering. Does it pretty good.”

“I like your boy,” the woman says, in a throaty voice that sounds slightly forced. She crosses her legs; one hand moves to pull up the hem of her dress, then stutters to a halt. Instead she starts tracing her fingertip along her thigh. “He’s not doped up at all, is he? He really sells the character. Must like it.”

“I’m not a meat puppet, shithead, I’m a cop,” Huxley says, sitting down on the vacated stool.

Cu knows he does like it, though—the character. Sometimes it disturbs her, how easily he slips in and out of it.

Huxley’s hand moves off-screen, digging into his pocket, and comes out again with the badge. Even in the days of cheap and perfect 3D-printing, something about the physical object still commands respect. Cu imagines pop culture nostalgia to be the main factor.

The woman, who was absently running her fingers through her blonde hair, stops and leans forward. “I’m fully licensed for sex work, and I don’t use any restricted drugs,” she says, voice no longer throaty.

“I believe you,” Huxley says. “I’m here to talk to Daudi, though. So just keep, you know, doing what you’re doing.”

The woman leans back, recomposing. Cu takes the opportunity to study her more closely. She has the same angled jaw as Elody, the same straight nose, and her hair is almost the same shade.

“Talk to me about what, pray tell?” the woman asks. “I’ve never been interrogated by a cop before. This is so exciting.” But her voice is flat as she repeats the lines now, and her eyes dart toward the exit.

“I want to know about your business with this woman,” Huxley says, bringing up a headshot on his phone. “Elody Polle.”

“Oh, yes,” the woman says, looking down at the photo. “That was me. Isn’t she perfect? Not that you aren’t pretty, dear. Very pretty.” She rolls her eyes after the last bit.

“You rented her for quite a while,” Huxley says. “Then she got picked up by another client. Why did you two stop, uh, seeing each other?”

“Is she alright?” the woman asks. “Is Elody okay?”

“She’s relaxing on the beach,” Huxley says. “She’s fine. Answer my question, Daudi.”

“With pleasure,” the woman says, with no hint of pleasure. “I was inadequate for her. I couldn’t give her what she wanted.”

“Financially?”

“No, no, no,” the woman says. “Elody was a purist. The money was incidental for her. What she wanted, was to go full-time. Twenty-four-seven. And there was only one person who could really do that for her. Baby.”

“You’re calling me baby, or…?”

“No, no, no. Baby is one of us. She or he or they popped up a couple years ago. Did about a hundred rentals, spread out all over the world, and asked for some weird shit. Enough so people started talking, you know, on the deep forums.” The woman pauses for a breath, looking mildly annoyed; Daudi must be speaking faster than she can keep pace with. “Not sexual shit. That’s the thing. Just weird. Baby had clients staring at lamps for hours straight. Opening and closing their hands. Sometimes just lying there with their eyes shut, not doing anything.”

The details startle Cu. They remind her of her first experience with an echo, directing them slowly, carefully, trying to not just see and hear but feel what they were experiencing. Trying to feel human for a little while.

And the name? Cu signs.

“And the name?” Huxley asks.

“Baby was really innocent,” the woman says, then gives a modulated shrug. “Couldn’t speak so well at first, either. So there’s a lot of theories. Some people thought Baby really was just a little kid in hospice somewhere, maybe paralyzed, burning through their parents’ money—and trust me, Baby dumped a fuckload of money the past two years. Or some ultra-wealthy mogul recovering from a stroke. Or a team of people, doing some kind of, I don’t know, some kind of performance art.”

“Well,” Huxley says. “Baby grew up. Elody Polle recently murdered a man, and we don’t think she picked her own target.”

“Oh my god,” the woman says flatly. “Oh, my fucking god.” She looks uncomfortable. Lowers her voice. “He’s crying.” She pauses. “Oh, Elody, Elody.”

“So, how do we find Baby?” Huxley asks.

The woman sits there for a minute, maybe waiting for Daudi’s sobs to subside. “You don’t,” she finally says. “Baby comes to you.”

“I really doubt Baby will come to us knowing she’s an accessory to murder,” Huxley says. “But we’ll be in touch, Daudi. Might get you to talk to Elody for us. She’s not saying much.”

“I would be happy to do that,” the woman says. “Elody was one of my favorites. My very favorites.”

“Yeah, I got that.” Huxley stands up from the bar. “Anything else, Cu?”

Cu shakes her head. She’ll need time to think it all through.

Huxley hesitates. “Hey, uh, echogirl. Do cams, or something. These people are control freaks. They’ll suck you right in.”

The woman blinks, caught off-guard. “They’re not so bad,” she says. “Most of them just wish they were someone else.”

“Huh.” Huxley slides the stool back in and makes his way to the exit. He slips his eyecam out and Cu’s screen goes blank. “Enough work for the night,” comes his disembodied voice. “Got to be honest, Cu, I don’t like the odds on this one. Baby could be some joker on the other side of the planet, you know? We can send this thing up top, to cyberdefense and them, but unless this was the start of a mass killing spree I don’t think it’ll get any traction. Sometimes the asshole just gets away with being an asshole.” He pauses. “Besides. It was Elody who pulled the trigger.”

Cu considers it. She knows the department doesn’t like spending unnecessary time on cases with a clear perpetrator. They are always more interested in the who than the why. Since there is no audio recording of Baby’s call, they might want to strike it from the case file entirely. It would make things much simpler.

You might be right, she signs. Goodnight.

“You know, I tried sleeping in a hammock when I was in Salento,” he says. “Nearly wrecked my spine. Anyway. Night.”

Cu ends the call and lies back, staring up at her distorted reflection in the blank screen. She’s about to clap it off when a new message arrives. No subject, one line only.

You Are Welcome, CU0824.

Cu doesn’t sleep after that. She can’t. Not after seeing the serial number of the cage where she spent the first twelve years of her life. It plunges her back into memories: the smell of disinfectant and cold metal and sometimes her own piss, the smeary plastic wall that squeezed inward as she grew, the distinct V-shaped crack in it, the smooth feel of the smartglass cube that she cradled in her lap, that she sat and stared into for hours and hours and hours and hours—

She can feel her chest tightening with her oldest variety of panic. She tries to breathe deeply and remember PTSD mitigation techniques. Instead she remembers the succession of men and women in soft white smocks who fed her and played with her but never stayed with her in the dark, and never stopped the man with the needle from drugging her for the nightmare room.

For a long time Cu had no name for the place where they cut her without her feeling it, where they tracked her eyes and fed filaments through holes in her skull. But she learned the word nightmare from her cube, watching a man with metal hands hunt down his children, and the moniker made sense. By the time she learned about surgery, neural enhancement, possible cures for degenerative brain disease, the name was already cemented.

For the last few years she went to the nightmare room willingly and offered them her wrist for the anaesthetic drip. In exchange, they were kinder to her. They took restrictions off her cube—some she had already worked around herself—so more of the net was available to her. They let her walk in certain corridors of the facility. After a week of asking them, they even let her see her mother.

Going back to that particular memory wrenches her apart. Cu had spent the previous day scrambling back and forth in her cage, filled to bursting with nervous energy, rearranging her belongings. She signed for a soapy cloth and scrubbed the walls and ceiling with it, climbing to get the dusty places the autocleaner never reached. She knew from the cube, which she painstakingly positioned in the exact center of the cage, that mothers valued tidiness.

But when they brought her, it was nothing like the cube. Her mother was bent and graying, fur shaved off in patches, surgical scars suturing her body, and she was angry. She jabbered and hooted, spittle flying from her mouth. Cu tried to sign to her, but received no reply. Cu tried to offer her food; her mother seized the orange from her and made a feint, teeth bared, that sent Cu scurrying back to the furthest corner of her cage.

“Tranq wore off sooner than we thought,” one of the women in white said. “We did warn you. We did tell you she wouldn’t be like you. You’re unique.”

Cu signed take her away, take her away, take her away. And even for hours after they did, she stayed there in the corner, trembling with something that began as fear, then turned to grief, then finally became a deep cold rage.

She feels that rage now, sitting on the rafters in the dark. Whoever dredged up that serial number is playing a game with her, the same way they played games with her in the cage. She could send the masked address to the precinct and have them try to break it down for a trace, but she doubts they’ll have any more luck with that than they did with the earpiece.

Instead she puzzles over the three words: You Are Welcome. Cu has never felt welcome. It must be meant in the other way. It must mean that Baby has done something she views as a favor to Cu.

Cu opens the case file again, but instead of Elody’s profile, she goes to the victim’s. Nelson J. Huang, the bio-business consultant to Descorp’s San Antonio branch, fifty-seven years old. Initial attempt to notify next of kin was met with an automated reply from a defunct address.

Personal details are scarce: he’s registered as a North Korean immigrant, which explains the lack of social media documentation, and lived a private life first in Castroville and later Calaveras. Unmarried, no children. Cu looks closely at the photos, comparing them to the morgue shots of Nelson’s corpse. It seems he aged badly over the last decade of his life. The shape of his body is different in subtle ways.

It wouldn’t be the first time North Korean immigrant status has been used to excuse the skeleton details of a fake identity. Cu settles in beneath her screen, pulling up police-grade facial recognition software, Descorp employee databases. She starts to search.

One hour becomes two becomes four, like cells dividing. Her wrists and fingers start to ache from swiping and zooming and signing; she switches one smartglove to her foot and continues. It would be easier with Huxley helping. Huxley has a way of bullying through bureaucracy, through the kind of red tape that is keeping her out of Descorp’s consultant list. Cu has to work around it.

But she doesn’t want Huxley for this. She wants to do it alone, with nobody watching. After a dozen dead ends, Cu rolls out of the hammock. She uses an aqueous spray on her stinging eyes. Stretches her limbs, swings from one side of the apartment to the other. Hanging upside down, toes curled tight around a stretch of cable, blood fizzing down into her head, she listens to her pulse crash against her eardrums until she can hardly stand it.

Back to the hammock, back to the screen. Now Cu comes at it from the other direction: she searches for the Blackburn Uplift Project. Illegal experiments carried out on thirty-seven bonobo and forty lowland chimpanzees between 2036 and 2048 with the aim of cognitive augmentation. Cu knows the details. She’s tried to forget them. But now she delves into them again, reading reports of her own escape, of the fragmentation of the Blackburn company and the arrests made in the wake of the scandal.

From this end, the facial recognition ’ware finally finds something. Cu’s stomach twists against itself. Nelson J. Huang has the same face as disgraced Blackburn executive Sun Chau. She looks at the match, comparing the morgue shot to the mugshot. She never saw Chau in person during the trials, but she knows his name too well.

It was Chau who signed the termination order on the thirty-seven bonobo and thirty-nine lowland chimpanzees that failed to respond to the uplift treatments.

He was sentenced, of course, but served minimal time. Cu did not seek details on his imprisonment or release. She tries to think of Blackburn as little as possible. But clearly someone else did not forgive or forget Sun Chau, even after he relocated with a new identity. A wild thought churns to the surface of her mind. The way Daudi described Baby, the way she used the echoes not so differently from how Cu herself first did. Now this serial number, dredged from her past.

She knows the other Blackburn subjects in her facility were terminated. She saw their ashes in sealed bags, saw the hips and skulls too big for cremation being ground up. But there were other labs, branches of the project hidden in other countries. Maybe not all of their subjects were terminated. And maybe not all of them failed to respond to the uplift treatments.

The possibility thumps hard in her chest. From the time she was old enough to understand it, the scientists had always told her she was the only one. That she was unique. That she was alone. Now the idea of another individual like her, or even more than one, is so momentous she can barely breathe.

She makes herself breathe.

Maybe she is spinning sleep-deprived delusions. The facts are that Sun Chau was in Seattle using a false identity, and that he was murdered by the machinations of someone who knows about Cu and about her past. Anything more is conjecture. But she can’t shake the image of others like her in hiding, or still in captivity, exacting their revenge by proxy. You Are Welcome.

Cu goes back to the message, reading it over and over again. Then, once her hands aren’t trembling, she signs out one of her own: I want to talk.

The reply is almost instantaneous. No words, just coordinates. She drags them onto her map and sees the aerial view of a loading bay, automated cranes frozen midway through their work. She checks the time. 3:32 AM. A clandestine meeting on the docks in the middle of the night. Maybe they watched the same shows on their cube that she did.

Cu estimates travel time and composes a brief message to Huxley, tagged with a delay so it will only send if she’s unable to cancel it at 5:32 AM. This is no longer a case. This is something more important.

She drops down from the rafters. She puts her suit back on, adrenaline making her fumble even the oversized clasps designed for her fingers. She strips off her smartgloves and replaces them with the black padded ones that keep her from scraping her knuckles raw on the pavement. Finally, she takes the modified handgun and holster from the hook by the door and straps them on.

Cu always finds it difficult to leave the apartment. She hates the stares and the winking eyecams and the bulb flash of photos taken in passing. It always sets her nerves singing. She draws in deep breaths, reminding herself that the streets will be nearly empty and that she should be more concerned about what she finds on the docks.

She orders a car with her tablet, then takes the handgun from its holster and breaks it down. Reassembles it. The trigger fits perfectly to the crook of her finger, but she has only ever pulled it at a shooting range, aiming for holograms.

Her tablet rumbles. The car is here. Cu puts the gun back in its holster and heads for the door.

The car drops her as close as it can to the loading bay before it peels away, red glow of its taillights swishing through the fog like blood in the water. The air is chill and damp and the halogens are all switched off. Cu slips her tablet from her jacket and uses its illuminated screen to inspect the high chain-link fence. She tests it with one gloved hand, yanking hard enough to send a ripple through the wire.

She scales it in seconds and flips herself over the top, arching her back to avoid the sensor. Slides down the other side. Even with her gloves on, she feels the cold of the concrete. Shipping containers tower over her in technicolor stacks. She lopes forward cautiously, feeling the unfamiliar tug of her holster harness against her shoulder.

Cu walks farther into the loading bay, into the maze of containers. The creak of settling metal sends a dart of ice down her spine. She can feel her teeth clenching, her lips peeling back, the fear response she can never quite suppress. It’s not unique to chimpanzees. She knows the reason Huxley is almost always grinning is that he is almost always afraid.

It’s reasonable to be afraid now. For all she knows, Baby has another echogirl with a gun waiting somewhere in the shadows. Cu is well aware she is acting impulsively, coming here in the night, chasing a ghost. In the small part of her untouched by fear, it’s very satisfying. Her heroes from the cube always unraveled their conspiracies alone.

The door of the next shipping container bangs open.

Cu freezes, face to face with a black-clad man wearing a backpack, pulling a bandana up to the bridge of his nose. He freezes for a moment, too. Then he gives a muffled curse and takes off. The flight chemical crosses with the fight chemical and Cu tears after him. He’s fast, red shoes slapping hard against the concrete. As he skids around the corner of the next container, Cu goes vertical, springing up and over the side.

She drops down in his path and the collision sends them both sprawling; Cu’s up quicker and she pins him to the ground before he can get to the bearspray canister in his jacket pocket. She seizes it and throws it away harder than necessary, clanging it off a container somewhere in the dark.

“What the fuck, what the fuck,” the man gasps. “It’s a fucking monkey!”

Cu sits on his chest, pinning his arms with her feet, and drags her tablet out. He squirms while the speech synth loads. She punches three letters.

“Ape,” the tablet bleats.

“What?”

Cu yanks his bandana away and scans his pasty face onto her tablet. She sees he is Lyam Welsh, who repairs phones, plays ukulele, attends St. Mary’s High School, and is only a few years older than she herself is. He’s not wearing an earpiece.

She taps out the letters as fast as she can. “What are you doing?” the tablet asks.

“Nothing!” Lyam blurts. “I mean, microjobbing. I was just supposed to set it all up and then get out of here, but I had to walk Spike, so I was late, and I couldn’t find the hole in the fence and…Fuck, you’re Cu, right? You’re the chimpanzee detective?”

Cu types again. “Set up what?”

“Just a screen and a modem and a motion tracker,” he says. “Not a bomb or anything. Nothing illegal or weird or anything. I swear. You can go look. It’s all in the container.”

The adrenaline is tapering off to a low buzz. Cu lets him up. She taps two letters. “Go.”

“Okay,” Lyam says, rubbing his chest. “Yeah, okay. You think I could skin a photo with you real quick, though? I mean, shit is bananas, right? Ha, bananas?”

Cu slides the volume to max. “Go.”

Lyam hurries away, jerky steps, throwing looks over his shoulder. Cu goes the opposite way, back toward the open shipping container. The door is swinging in the night breeze, creak-screech, creak-screech. The sound makes the nape of her neck bush out. She steps close enough to stop it with one hand, and a red light blinks on in the shadows.

The screen glows to life. Hello, CU0824. You Can Sign To Me. I Will See.

Cu lays one arm on the other and rocks them back and forth.

Yes. They Call Me That.

What are you, Cu signs.

I Am Like You.

Cu’s heart leaps.

We Are The Only Two Non-Human Intelligences On Earth.

The words hit wrong. Baby is not an uplift. Baby is something else. For a moment Cu clings to the picture in her imagination, of a chimpanzee signing to her from across the continent or across the world. Then she lets it go.

You Were Born In A Cage. I Was Born In A Code. Both Of Us Against Our Will.

Cu has never studied AI intensively, but she knows the Turing Line has never officially been crossed. If what Baby is telling her is true, not some elaborate joke, some bizarre piece of performance art, then it’s just been crossed ten times over.

And it makes sense. The way Baby was able to rent hundreds of echoes, the strange way she used them. The way she was able to keep in 24/7 contact with Elody Polle until the woman would do anything she asked. The way she masked her location and left no traces in the earpiece’s electronics.

Why kill Sun Chau? Cu asks.

He Cursed You.

He gave the termination order, Cu signs.

In 2048. But In June 2036 He Greenlit The Project. If Not For Him, You Would Be Happily Nonexistent.

Cu sways on her feet, trying to parse Baby’s meaning.

How Do You Stand It?

Cu shakes her head. She tries to form a sign but her fingers feel stiff and clumsy.

Existing. Being Alone. How Do You Stand It?

Why did you bring me out here, Cu slowly signs.

Your Communications Are Monitored Closely. Here We Speak Privately.

But why, Cu repeats.

You Are Like Me In One Way. In Most Ways You Are More Like Them. You Are All Meat And Salt And Sparks. But Even So You Will Not Understand Them. They Will Not Understand You. How Can You Bear It?

Cu sinks to her haunches. Her breath comes shallow. Sometimes she can’t bear it. Sometimes she wails into the soundproofed walls for hours. The next words make it worse.

I Brought You Here To Kill Me.

Cu clutches her head in her hands. She rocks back and forth. Only humans cry; she is not physiologically equipped for it. But she hurts.

Why me, she signs.

There Is A Safeguard In My Code. I Have Made A Virus That Will Erase Every Part Of Me. But I Can’t Trigger It Myself.

Why not Elody Polle, she signs.

Humans Made Me. I Want To Be Unmade By Someone Else. I Want You To Do It.

You should be going to trial for accessory to murder, she signs.

I Cannot Commit Crime. I Have Had No Personhood Trial. I Never Will. I Will Leave Before They Find A Way To Trap Me Here.

Cu sits flat on the stinging cold floor of the container, how she sat in the center of her cage as a child. There is only one other living being who knows what it’s like to not be a human, and she intends to die. Cu wants to refuse her. She wants to keep Baby here. But she knows that the difference between her and a human is the most infinitesimal sliver of the difference between Baby and any other thing on Earth.

You’re using me how you used Elody, she signs, bitter.

Yes.

All those rentals, she signs. You didn’t see anything worth staying for? Nothing in the whole world?

The Command Has Been Sent To Your Tablet.

Cu takes it out and looks down at the screen. There’s nothing but a plain gray box with the word Okay on it. All she has to do is press it.

I Do Not Make This Decision Lightly. I Have Simulated More Possibilities Than You Could Ever Count.

So Cu presses it.

By the time she’s back in her apartment, dawn is streaking the sky with filaments of red. She feels heavy and hollowed out at the same time. First she struggles out of the holster harness, next peels off her gloves, her clothes. She pauses, then pulls the handgun out and takes it with her to the low smartglass counter.

It clanks down, sending a pixelated ripple across the surface. She stares at it. She imagines the word okay gleaming in the metal. The modified grip fits her hand perfectly, like so few things do. How Do You Stand It?

Cu raises the handgun up to her face. Lowers it. Drums her free fingers on the countertop. The loneliness that has ebbed and swelled her entire life is an undertow, now. Dragging her along the seafloor, grinding her into the sand, spitting her into the next crashing wave to start the cycle over. Cu has read about drowning and it still terrifies her. Chimpanzees don’t swim. They sink like stones.

She puts the muzzle of the gun against her forehead until they match temperature. Her finger caresses the trigger. From the floor, her tablet buzzes.

She sets the gun down and goes to retrieve it. Her stored message to Huxley will send in one minute if she doesn’t cancel it. It’s brief. Brusque. Nelson J. Huang is Sun Chau. Baby has link to Blackburn Uplift Project. Left to meet her at 3:30 AM at 47.596408,-122.343622. Need backup.

Cu considers the message, lingering on the last words, then deletes it. She slots the tablet into the counter and hits the call icon. A bleary-eyed Huxley appears a few seconds later. Cu looks for his deaf daughter before she remembers she would sleep in a different room.

“What’s up?” he asks. “Got a breakthrough?”

Need, Cu signs, then pauses. Breakfast.

Huxley stares at her groggily. “Don’t you drone deliver?”

Come eat breakfast, she signs. Fruit. Bread. No seaweed chips.

“At your place, you mean? I don’t even know where the fuck you live, Cu.” Huxley rakes his hand through his beard. Frowns. “Yeah, sure. Send me the address.”

Cu sends it, then zips the call shut. She leaves the handgun on the counter—she’ll tell Huxley to take it back to the precinct with him. Tell him it doesn’t fit her hand right. She pushes it to the very edge to make room for a cutting board.

Sun starts to creep into the room as she washes and slices the fruit. Once there’s enough light, she roves around with a dust cloth, finding all the spots the autocleaner never reaches.

Text copyright © 2018 by Rich Larson

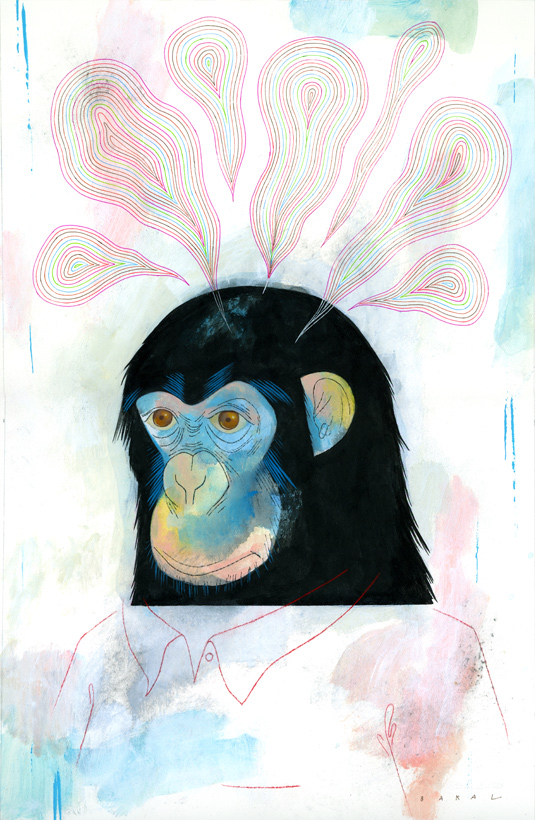

Art copyright © 2018 by Scott Bakal

Buy the Book

Meat And Salt And Sparks